TRICONTINENTAL

Glauber Rocha

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

FOOTNOTES

FOOTNOTES

Tricontinental, any camera that is open to the evidence in the Third World is a revolutionary act.

Tricontinental, the revolutionary act is the product of an action that will become a reflection on the struggle.

Tricontinental, the political choice of a filmmaker is born the very moment when light pierces his film. And that’s because he chose light: a camera on the open Third World, an occupied land. On the streets or in the desert, in the jungle or in the cities, the choice is imposed and, even when the material is neutral, after editing this material becomes a discourse against substance. The discourse might be imprecise, vague, savage, irrational. But it is a tendentious rejection.

Tricontinental – is the film the important thing? What is a tricontinental film? A producer is like a General here. Instructors in Hollywood are like the ones in The Pentagon. No tricontinental filmmaker is free. I do not mean free from prison, or from censorship, or from financial obligations. I mean free from discovering within himself a man from three continents; but he doesn’t become a prisoner in it; rather he becomes freer there: the prospect of individual failure fades away. To quote Che:

‘Our sacrifice is conscious; it is the price of freedom’.

Tricontinental – any other discourse is beautiful but harmless, rational but exhausted, cinematic but useless, thoughtful but helpless, and even lyricism, while it floats in the air, is born from words and becomes architecture, it then becomes a passive or sterile conspiracy. Here, to recall Debray, the word is made flesh.

Tricontinental – auteur cinema, political cinema, against cinema, all this is guerrilla cinema; in its origins it is savage and imprecise, romantic and suicidal, but it will become epic/didactic.

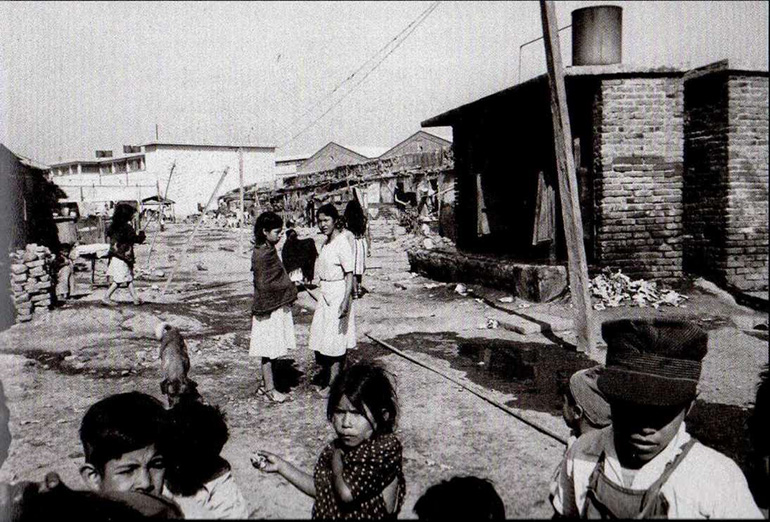

Mexican cinema suffers from nationalist sickness. Mr. Luis Buñuel, an Ibero-American, considers ¡Que viva México! to be an ‘artistic’ film. Eisenstein did not understand the spontaneity of Aztec architecture or the extraordinary magnificence of the desert or the volcanoes. His attempt at aestheticising the New World can be compared to an attempt to bring the Word of God (and the interests of the conquistador) to the Indians. Culture belonged to the Indians too. This Mayan, Aztec, Inca Culture was discovered and civilized. In the land of magic, the Indian was captivated by the walking volume that was the horse: this four-legged animal was a War Tank, a sacred and invincible animal. Nowadays, several centuries later, Ho Chi Minh is resisting the invader’s technological advances.

Mexican cinema took the images of Eisenstein dressed as a Jesuit, then mixed these shots with an amazing Hollywood-like technique and transformed it all into nuestro México. The industry defended by laws and unions, nuestro México, romantic nationalism and the illusion of history, nuestra revolución; sombreros, mujeres y sangre1.

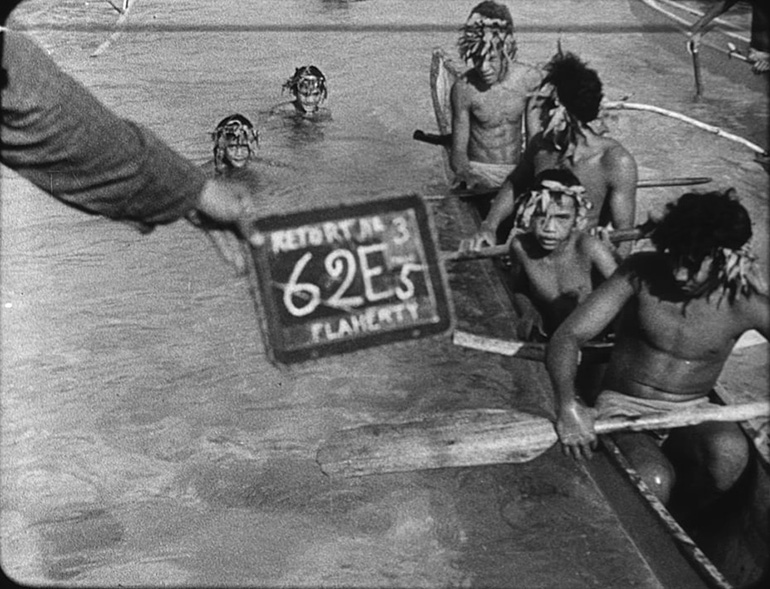

Sun above natives: Murnau (Gauguin), Flaherty. In their works the natives turn into bodies and seas, smiles and tragedies, in the same way that these Latin American ports are a violent and liberating paradise; the ports where, to have and have not, Bogart feels and suffers from the exoticism of revolutions. Before Latin American filmmakers had the right to switch on the motor of their old cameras, the art and business of big companies had given us their cinema and the rules of their business.

In Mexico, anti-Mexican films were (and are) banned. Thus, a small fraction of the American production that treats Mexicans as cowards is banned. But the worst thing is that in most of the films from Churubuzco Studios2, Mexicans are either cowards or naive creations of nature. The Mexican film industry, in order to defend itself from this slander, imitates it, in the same way that socialist cinemas imitate the Russian cinema that imitates the American formula. Mexican nationalism isolated Mexico from Latin America. It is not by chance that, except for a few young filmmakers who have just begun to betray nuestro México, Mr. Luis Buñuel is considered a marginal filmmaker. But in his comedies and melodramas, also filmed in Churubuzco, we can find the earliest essays about Latin American civilization, after the Catholic, Zapatista and Eisensteinist apocalypses.

On both pampas and asphalt, Argentina brought everything, stone by stone, from Europe. Argentina, Che’s mother country, while discussing in perfect French the aesthetic of the absurd, did not suspect that ‘Perón’s progress was not development...’ Penniless aristocrats were willing to sacrifice food for the sake of a Dior tie. The isolation of the pre-Antonioni bourgeoisie in Argentinian films was limited by undernourishment. But they didn’t say that word: while Borges’/Cortázar’s writing foresees many of the nouveau roman experiences, time could not be articulated (or inarticulated) in pre-Resnais films. As it was solitary, Argentinian cinema discovered Style before History. A character by Torre-Nilsson, disciplined in a vague universe reminiscent of Bergman, achieves nothing more than discipline. It is an ahistorical discipline because it is acritical. It does not expose itself to the light, it does not allow itself to be distorted, but it conspires in the shadows around a world that does not exist culturally in its superstructure. Here, the word is not made flesh; it is shadow and light (gray and black) in a country that does not fit with America.

What remote guilty conscience of isolation caused within Che, a citizen from Argentina, the legendary existence of the Latin American man and –in a stronger impulse– of the tricontinental man?

A cinema that is already in decline before it has developed, in the same land and time as Che’s, is a cinema that cannot be saved by technique or by an aesthetics manual. More than any other tricontinental cinema, Argentinian cinema needs a Vietnam.

Viva América, in Cuba there is a great deal to be done. It is a cinema that, while focusing on educational movies, has an important revolutionary contribution ahead: to completely detoxify itself from socialist realism. ‘To simplify the terms of these controversies, which involved artists and certain functionaries: some championed an art relatively close to socialist realism, while some others (and most artists) championed an art that did not renounce the achievements of the avant-garde. The defeat of the former viewpoint was confirmed when Che, in Man and Socialism in Cuba, harshly criticized socialist realism, but without considering the latter viewpoint entirely satisfactory: in his opinion, they should not be content with that position, they should go further. But to do so, one must begin from somewhere, and the avant-garde seemed to be a good starting point, if not a point of arrival.’ (Jesús Díaz)3.

Other Latin American nations (Guarani, Amazonian and Andean) never possessed a camera or were rarely able to switch on its engine, except in official news footage showing Generalíssimos and their medals.

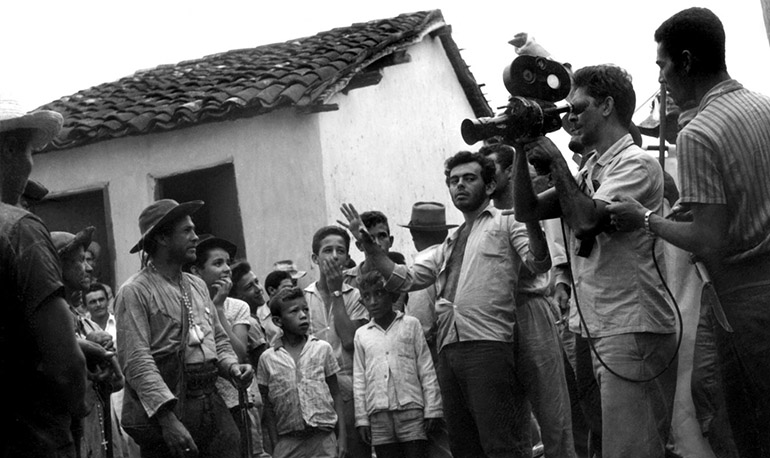

Brazil, tricontinental, Latin American, speaks Portuguese. Regarding the practice of the so-called Cinema Novo, one must know that the Portuguese are less fanatical and more cynical than the Spanish, and they have left us a legacy that is less nationalistic. Maybe that is why Brazilians do not have the Mexican complex or the Argentinian frustration. And that is why Brazilian independent filmmakers lost their religious respect for cinema. They preferred not to ask for permission to enter this sacred universe and, even though they were left-handed, they grasped their cameras. Maybe because intellectuals and critics wrote it so many times (to the point of convincing the public to intimidate certain filmmakers) that ‘Portuguese is an anticinematic language’, Cinema Novo considered it absurd not to turn words (and music) into cinema: Brazil is a verbal nation, it is talkative, energetic, sterile, and hysterical. Brazil is the only Latin American country that did not have bloody revolutions (like Mexico), baroque fascism (like Argentina and other places) or political revolution (like Cuba). As a sad compensation, it has a growing cinema. Its production will total sixty films this year, a number that will increase, even double, next year. More than a hundred young filmmakers submitted 16 mm and 8 mm films in the last two ‘amateur cinema’ contests, and the public, disappointed by the recent footballing defeats, debates each national film with a passion. Rio, São Paulo, Salvador and other big cities have Art Houses, two film libraries, more than four hundred film societies (even in the most remote part of the Amazon there is a film society). In Rio and São Paulo, Godard is now as popular as De Gaulle, and there are moviegoers there who can compete with experts from the Cinémathèque Française. In Brazil, and especially in Rio, there has been a real cinema party going on for the last five years.

Tupi is the name of an Indian nation that is characterized by its intelligence and lack of craft skills. Cangaço is an anarchic, mystical guerrilla, and it means violent disorder. Bossa is a special style of style, and also a style of feinting, of threatening to the right and punching from the left, with a rhythm and an eroticism. This tradition, whose values are questioned by Cinema Novo films, absurdly draws a tragic caricature of a melodramatic civilization. There is no historic density in Brazil. There is an ahistorical dissolution, created by coups d’état and counterattacks, which are directly and indirectly related to imperialists’ interests, dragging the national bourgeoisie along with them. The populist left wing always ends up signing agreements with the repentant right wing in order to begin, once again, ‘redemocratization’. Until April 1964 –the fall of Goulart– most Brazilian intellectuals believed in ‘revolution through words’.

The Latin American political avant-garde is always led by intellectuals and here, very frequently, poems precede guns. Popular opera – music and revolution go hand-in-hand and the legacy comes from Spain. Today, in the Brazil of unforeseen reconciliations, the urban Left is defined as ‘festive’. Marx is discussed to the sound of samba. However, this does not stop students from violently protesting in the streets, professors from being imprisoned, universities from being closed down, intellectuals from constantly writing protest manifestos, or unions from being occupied. Criticism is made at the moment it is produced, and on top of that: the advertising, the distribution and the exhibition are produced. Politics as the art of opposing oppressive systems.

With regard to audiences that are more illiterate than in developed countries, a cinema that has accumulated all the disadvantages of tricontinental cinema does not communicate easily. Communicating means, in the populist vocabulary, stimulating revolutionary feelings.

This cinema produces a shock at several levels, which represents a different way of communicating. A Cinema Novo film is polemical before, during and after its screening, and its very existence is a new element in the paradise of inertia. Thus, Barren Lives (Vidas Secas) documents farmers, while The Guns (Os Fuzis) is an antimilitarist attack that builds on the discourse in Barren Lives. In turn, this discourse is transformed into agitation in Black God, White Devil (Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol), a furious political act that is later calmly discussed in The Dare (O Desafio). While Barravento and Ganga Zumba talk about and with black people, and The Deceased (A Falecida) is the urban version of Barren Lives, this does not mean that they neutralize the possibilities contained in The Unscrupulous Ones (Os Cafajestes) and The Big City (A Grande Cidade). And though from Plantation Boy (Menino de Engenho) to Land in Anguish (Terra em Transe), or from the latter film to Dahl’s next, The Brave Warrior (O Bravo Guerreiro), Cinema Novo seems to become destabilized in the difficult endeavor of individual expression, it soon restores a cinematic concerto that constitutes a political act in a continuous polemic.

The technique of past and present cinema in the developed world interests me to the extent that I can ‘use’ it, in the same way that American cinema was ‘used’ by some European filmmakers. What does ‘using it’ mean? Using, as a method, certain key cinematic techniques, general cornerstones that in the technical evolution transcend each individual author and become part of the aesthetic vocabulary of cinema: if a ‘cangaceiro’4 is filmed in the desert, there is an implicit editing approach based on the Western. This approach is more related to the general style of the Western than to individual creators like Ford or Hawks. On the other hand, imitation originates from a filmmaker’s passivity towards cinema, born out of a suicidal need to take refuge in the established language, and thinking that if he can save himself by imitating, then he will save the film. In an interview in Cahiers, Truffaut said: ‘Almost every film that mimics Godard is unbearable, because it lacks the essence. It may copy his fluency, but it misses the desperation. It might copy his wordplay, but not the cruelty’5.

Most films by young directors are currently suffering from this ‘mal de Godard’. Only by directly enduring reality and by a continuous exercise of dialectical criticism can one go beyond the mythological imitation of cinematic technique, by using the wordplay in progressive imitations. Brazilian films such as Barren Lives, The Deceased and The Guns show how colonized filmmakers can use the technique of the developed cinema to promote an international expression. The problem is not so radical for Americans or Europeans, but if we look at films from socialist countries, we notice that very few of them are revolutionary. The attitude of most filmmakers towards their reality degenerates into a kind of calligraphic, academic cinema that clearly reveals a contemplative or demagogic spirit. And festivals, especially in programs of short films’, reveal a ‘Cinema Ltd.’, a series of harmless imitations that have been innocently manufactured using a Moviola and which unravel during screenings. Cinema is an international discourse, and national eventualities do not justify, on any level, the denial of expression. In tricontinental cinema, aesthetics comes before technique, because aesthetics has more to do with ideology than with technique. Technical myths such as zoom, direct, caméra à la main, couleur, etc. are just tools. The Word is ideological, and there are no geographical borders any more. When I talk about tricontinental cinema and include Godard it is because, when he opens up a guerrilla front in French cinema and attacks repeatedly and suddenly, with relentlessly aggressive films, then Godard becomes a political filmmaker, with a strategy and tactics that are exemplary in any part of the world. However, this example is useful regarding behavior.

I insist that a guerrilla cinema is the only way to fight the aesthetic and economic dictatorship of Western imperialist cinema, or socialist demagogic cinema. Improvisation based on circumstances, free from all the typical morality of a bourgeoisie that managed to impose, from the general public to the elite, their right of access to art.

My ultimate aim of a didactic/cinema cannot prevail unless it merges with the didactic/epic poem played out by Che. An inverted Western, with the nouns of the new poetics that come from a comprehensive revolution, will destroy idealist frontiers in cinema. While Buñuel, precontinental, operated by means of precise tracking shots, in tricontinental cinema we need to demobilise it and blow it up. When Che’s mise-en-mort becomes a legend, it cannot be denied, Tricontinental, that poetry has become a revolutionary praxis.

Originally published as Un cinéaste tricontinental. Cahiers du cinéma, 195, November, 1967, and included later in Portuguese with changes in the compilation book Revolução do Cinema Novo (Rio de Janeiro: Alhambra, Embrafilme, 1981). The Spanish translation can be found in La revolución es una eztétyka: por un cine tropicalista (ed. Ezequiel Ipar; trans. Ezequiel Ipar and Mariana Gainza; Buenos Aires: Caja negra, 2011). The present version adds some minor modifications to this one based on the Portuguese text. English translation is ours.

FOOTNOTES

1 / In Spanish in the original.

2 / The Churubuzco Studios were founded in 1944, with RKO Radio Pictures owning 50% of its shares.

3 / In French in the original.

4 / Canganceiros were bandits in the sertão region in the north-east of Brazil, particularly in the early decades of the 20th century.

5 / In French in the orginal. In Entretien avec François Truffaut, by Jean-Louis Comolli and Jean Narboni. Cahiers du cinéma, 190, May, 1967.