POPCORN AND GODARD: THE FILM CRITICISM OF MANNY FARBER

Andrew Dickos

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Termite art. Only an imagination as wily as Manny Farber’s could come up not only with the term but the concept. Coming out of the second generation of American film and cultural critics to inhabit the literary and higher middlebrow publications of the 1940s, Farber took his brash sensibility and merged it with an appreciation—far-ranging, complex, and subtle—for the beauty to be found in modernism and the best of distinctive yet often obscure pop culture. And some of the best pop culture was to be found in movies—not the highbrow canon alone—especially not the highbrow “white elephant” canon alone—but in all the unregenerate and stubbornly vigorous guilty pleasures found in movies that always far outweighed the official canon’s high-flown profundities in shaping our taste and consciousness. In other words, in the vibrancy and excitement of… termite art.

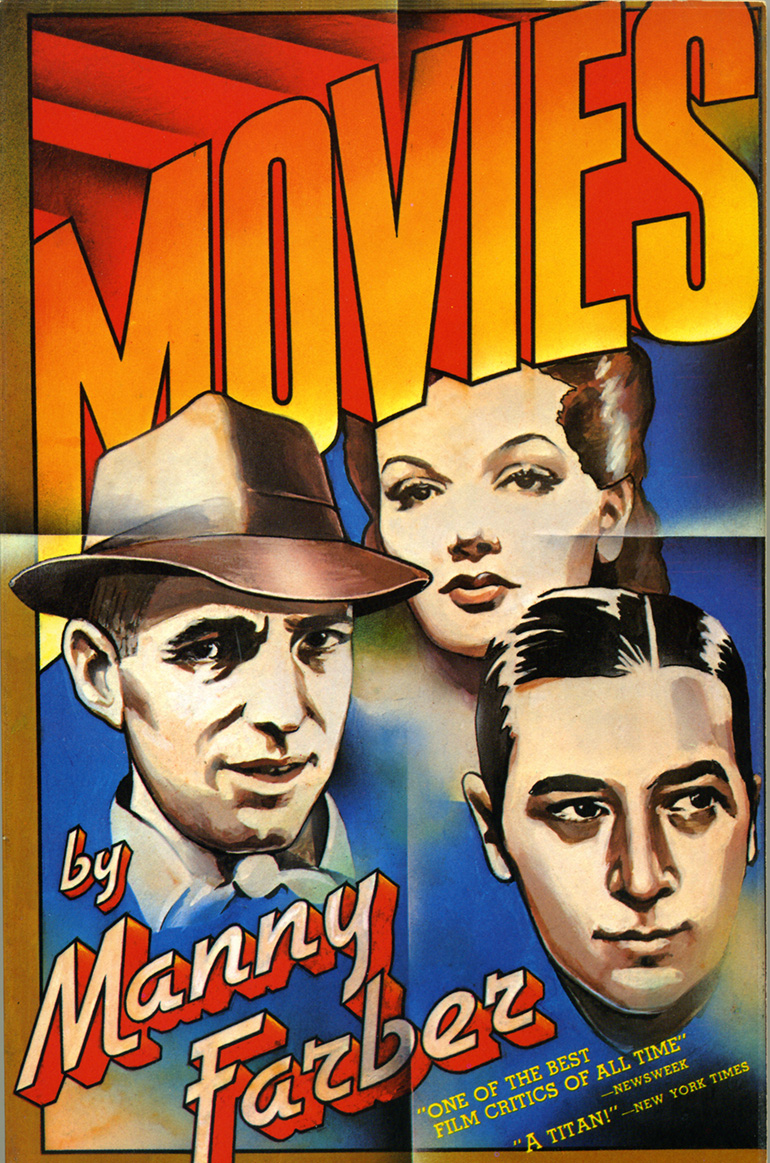

Farber started out as an art critic and drifted over to writing film criticism for the burgeoning little magazines that sprouted out of the Depression and served to give voice to the American Left in the 1940s. They were progressive and liberal, and true to the socialist-inspired New Deal promised by the Rooseveltian ethos and policies of the day. He became the film critic for The New Republic in 1942, and then went on at the end of the decade to write for The Nation, The New Leader, and other culture and arts journals throughout the 1950s and 60s. The choicest sampling of his best pieces were collected in Negative Space, published in 1971, the paperback edition of which (retitled Movies) had vivid colored graphic images of Humphrey Bogart, Gene Tierney, and George Raft on the cover designed by Stan Zagorski, a romantic and iconic evocation of the 1940s and a perfect complement to Farber’s respect for genre movies.

The range and excitement Farber displays in his criticism—and, more importantly, arouses in his readers—staggers the mind, and does so precisely because he is so at home with all he discusses. This fearlessness in a lesser writer would undermine his authority, expose him as a poseur. But not Farber. Farber prepares a meal of critical thought the way Julia Child prepared a simple dinner: intrepidly and without apology. No critic could write as he did about the joys of Chuck Jones’s Merrie Melodie cartoons in 1943 and also offer a lucid descriptive analysis of Chantal Akerman’s camera seduction of her audience in Jeanne Dielman, 23 rue du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) more than thirty years later (FARBER, 2009: 764-69)* Farber talks about the crisp, fast cutting of Don Siegel’s B actioners alongside Sam Fuller’s tabloid, and slightly but approvingly disreputable, melodramas, and both of these filmmakers end up in bed together with Jean-Luc Godard and his play with film language and ideas of Western culture. And, in Farber’s moviegoing universe, fittingly so.

Bottom: Pick on South Street (Sam Fuller, 1953)

Regarding Godard, Farber effectively summed up his work in October 1968 with the following:

‘Each new movie is primarily an essay about form in relation to an idea: a very deliberate choice of certain formal elements to expostulate a critique on young French Maoists; a documentary report on prostitution, poetic style; or a gray, somber, sophisticated portrait of an existential hero of confused commitments. (FARBER, 2009: 627) . . . Behind the good (Band of Outsiders [Bande à part, 1964]), bad (Woman Is a Woman [Une femme est une femme, 1961]), and beautiful-bad (Carabiniers [Les carabiniers, 1963] is visually ravishing at any moment, but nearly splits your skull) is the specter of an ersatz, lopsidedly inflated adolescent, always opposed to the existing order, primitivistic either in his thinking or in terms of conscience and feelings.’ (FARBER, 2009: 630)

Writing about those filmmakers and genres (film noir) he often disliked, but which many other critics admire, Farber still imparts insights that as criticisms can serve to elucidate as virtues the very weaknesses he derides. About Truffaut’s Jules and Jim (Jules et Jim, 1962), he observes: ‘Thanks to his fondness for doused lighting and for the kind of long shots which hold his actors at thirty paces, especially in bad weather, it’s not only the people who are blanked out; the scene itself threatens to evaporate off the edge of the screen.’ (FARBER, 2009: 539) An apt description for the naturalism, evocative of Renoir’s films of the mid-1930s, which so many others of us appreciate in Raoul Coutard’s cinematography for this film.

Manny Farber’s distinctive voice was heard in the quirky vividness of his prose, allusive yet specific, referential but rarely obscure. The lucidity of his critical mind describes the process of apprehending the filmmaker’s sensibility without mucking about in diffuse critical gobbledygook. It was also the epitome of a very masculine American sensibility that stood out in his words. Avid and fearless in his perceptions, Farber wanted us to join the party thrown by the filmmakers whose worlds he stepped into. No one had written about the great Preston Sturges as vividly as Farber did in 1954 (and few have since) in the essay he wrote with one William S. Poster (about whom nothing can be found). Farber tells us about Sturges that, ‘[s]ince there is so much self-inflation, false piety, and artiness in the arts, it was, he probably felt, less morally confusing to jumble slapstick and genuine humor, the original and the derivative together, and express oneself through the audacity and skill by which they are combined.’ (FARBER, 2009: 462) An almost perfect description of Sturges’s project, it defines his sensibility arising from the collision of verbal wit and physical comedy. He continues further:

‘Indeed his pictures at no time evince the slightest interest on his part as to the truth or falsity of his direct representation of society. His neat, contrived plots are unimportant per se and developed chiefly to provide him with the kind of movements and appearances he wants, with crowds of queer, animated individuals, with juxtapositions of unusual actions and faces. These are then organized, as items are in any art which does not boil down to mere sociology, to evoke feelings about society and life which cannot be reduced to doctrine or judged by flea-hopping from the work of art to society in the manner of someone checking a portrait against the features of the original.’ (FARBER, 2009: 463)

There is a remarkably consistent level of perspicacity in Farber’s forty-plus years as a critic. Unlike many critics, he didn’t develop his critical art over periods, but flew high from the start. More than twenty years after his celebrated essay on Sturges, he wrote with equal insight about the New German filmmakers Werner Herzog and Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Just before Fassbinder’s explosion on the international screen, Farber wrote in July 1975 about his Warholian debt in depicting sexual relationships in screen space:

‘His strategies often indicate a study of porn movies, how to get an expanse of flesh across screen with the bluntest impact and the least footage. With his cool-eyed use of Brecht’s alienation effects, awkward positioning, and a reductive mind that goes straight to the point, he manages to imprint a startling kinky sex without futzing around in the Bertolucci Last Tango style.’ (FARBER, 2009: 725)

And that voice has remained peculiarly alive and not at all dated—alive with the energy of a critic engaged in connecting the experience of the spectator to the formal compositions of the filmmakers he discusses. Consider, for instance, his summation of Antonioni circa 1962:

‘His talent is for small eccentric microscope studies, like Paul Klee’s, of people and things pinned in their grotesquerie to an oppressive social backdrop. Unlike Klee, who stayed small and thus almost evaded affectation, Antonioni’s aspiration is to pin the viewer to the wall and slug him with wet towels of artiness and significance. At one point in La Notte (1961), the unhappy wife, taking the director’s patented walk through a continent of scenery, stops in a rubbled section to peel a large piece of rusted tin. This ikon close-up of miniscule desolation is probably the most overworked cliché in still photography, but Antonioni, to keep his stories and events moving like great novels through significant material, never stops throwing his Sunday punch.’ (FARBER, 2009: 541)

Farber’s love of cinema very often came as that of a painter looking at a canvas and it included experimental cinema. We can connect his engagement with the formalism of non-narrative filmmaking, as in Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967), about which he astutely wrote in 1970:

‘The cool kick of Michael Snow’s Wavelength was in seeing so many new actors—light and space, walls, soaring windows, and an amazing number of color-shadow variations that live and die in the window panes—made into major aesthetic components of movie experience.’ (FARBER, 2009: 678)

to his love of the spatial contours of the Hollywood star’s magnetism now gone, when he wrote in 1971:

‘Since the days when Lauren Bacall could sweep into a totally new locale and lay claim to a shamus’s sleazy office, a world in which so much can be psychically analyzed and criticized through the new complex stare technique has practically shrunk to nothing in terms of the territory in which the actor can physically prove and/or be himself.’ (FARBER, 2009: 692)

Farber complemented his writing career with his painting and sculpture, carpentry, and manual labor. He worked on several construction sites around Manhattan in the early 1950s, and managed to connect the physicality of such work to his art making, in Greenwich Village during the time of the postwar abstract expressionist ferment and in the company of fellow artists like Hans Hofmann, Larry Rivers, and Robert De Niro Sr. and Virginia Admiral (the parents of actor Robert De Niro). There’s a thrilling romance one conjures up in the image of such a variegated life lived at a time when making paintings, sculpture, discovering movies, and redeeming their value in serious thought and writing mattered—at least in retrospect it mattered—with an enviable urgency so lacking in movie criticism today.

The breadth of Manny Farber’s knowledge about movies, presented with his idiosyncratic punch (one that makes Pauline Kael’s attempt at a critical slanginess often seem labored) and without insult to a caring and intelligent reader, resonated and lifted his writing as a discrete art of that very movie culture it illuminated. The shimmer of that writing remains, on the page, heard in one’s head, in the voice of a critic that still matters.

ABSTRACT

This paper alludes the context of the publications in which Manny Farber collaborated, mostly through the forties and the fifties, in order to outline the singularity of his approach to film criticism. Particularly, this paper addressees the diversity of styles and filmmakers he was interested in, without establishing hierarchies between the different cinematographic fields. Thus, through the relation of Farber’s quotes on Sturges, Antonioni, Fassbinder, Godard or Snow, it is shown how he was able to encompass a broad spectrum of films, from the popular to the avant-garde.

KEYWORDS

Manny Farber, Film Criticism, Popular Culture, Preston Sturges, Michelangelo Antonioni, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

FARBER, Manny (2009). POLITO, Robert (ed.), Farber on Film. The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber. New York: The Library of America.

ANDREW DICKOS

Author of Street with No Name: A History of the Classic American Film Noir (Univ. Press of Kentucky, 2002) and Intrepid Laughter: Preston Sturges and the Movies (Scarecrow, 1985). His third book, Abraham Polonsky: Interviews (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2012), is on the great Hollywood filmmaker blacklisted during the McCarthy era.

Nº 4 MANNY FARBER: SYSTEMS OF MOVEMENT

Editorial

Gonzalo de Lucas

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEW

The Law of the Frame

Jean-Pierre Gorin & Kent Jones

DOCUMENTS. 4 ARTICLES BY FARBER

The Gimp

Manny Farber

Ozu's Films

Manny Farber

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Manny Farber & Patricia Patterson

Nearer My Agee to Thee (1965)

Manny Farber

DOCUMENTS. INTRODUCTIONS TO MANNY FARBER

Introduction to 'White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art and Other Writings on Film'

José Luis Guarner

Termite Makes Right. The Subterranean Criticism of Manny Farber

Jim Hoberman

Preface to 'Negative Space'

Robert Walsh

Other Roads, Other Tracks

Robert Polito

The Filmic Space According to Farber

Patrice Rollet

ARTICLES

Hybrid: Our Lives Together

Robert Walsh

The Dramaturgy of Presence

Albert Serra

The Kind Liar. Some Issues Around Film Criticism Based on the Case Farber/Agee/Schefer

Murielle Joudet

The Termites of Farber: The Image on the Limits of the Craft

Carolina Sourdis

Popcorn and Godard: The Film Criticism of Manny Farber

Andrew Dickos

REVIEW

Coral Cruz. Imágenes narradas. Cómo hacer visible lo invisible en un guión de cine.

Clara Roquet