LOIS WEBER: THE FEMALE THINKING IN MOVEMENT

Núria Bou

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTOR

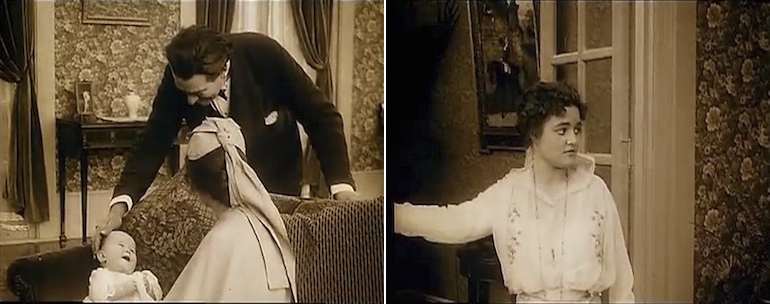

Lois Weber, in the role of the mother of a newborn baby, is about to call her husband, who is working in the city, at the moment where she discovers that their nanny has packed her bags to leave the house, because, as she writes in a note, she is not willing to work in such a solitary place. Right after reading these farewell words from her nanny, she lets herself be carried away by her own body, which, in a visceral way, leads her to the telephone. Weber reflects, restlessly looking at her surroundings, the fear that makes her be alone, but slowly overcomes her discomfort: with a reflexive countenance, she leaves the telephone and follows her decision with a shrug, sighing, as if trying to belittle her first fright; with a small smile she shows that she will not disturb her husband. But we can also see a certain inner satisfaction, the pride of knowing that she can be alone, of feeling self-sufficient. The main character of the short film Suspense (Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley, 1913) represents a good wife of Victorian appearance, while showing a decisive security that characterized the emancipated women of the new twentieth century. Indeed: in the fictions of the first decade of the century, the Hollywood’s creators drew attention, in their female characters, to what integrating the new empowering speeches of the New Woman could mean for a woman who had received a Victorian education. Lois Weber, as a woman and filmmaker, was sensitive to these inner female movements and felt the need to dramatize, in her characters’ bodies, this predicament: she managed to portray the appearance of a new female psychology, by visualizing in a complex and contradictory manner the difficulty of becoming a woman in the modern era.

1. The body of thought of an actress/filmmaker

Suspense, a ten-minute short film, is an extraordinary avant-garde film in which the main action is sometimes seen in a parallel way, sometimes using a split screen, a single segmented shot –in this case in three triangles– that frames different scenes. In this small exploit of suspense, we can see the pleasure of experimenting with the cinematic language and we notice a constant and meticulous framing and planning research1. Even if the film is also signed by her husband Phillips Smalley, her own writing will start to take shape, the one of a filmmaker who will afterwards, and by herself, continue to prove that precision was key to express intensely what was happening on the screen. Suspense is an absolutely controlled short film, an exploit of rationality in the use of analytic editing that shows the concise style of Lois Weber. Thus, it would not be strange if she herself had written the script, as she had been the scriptwriter of almost all the films she directed. Lois Weber, who also produced most of her films, had said that ‘a real director should be absolute’ (WEBER in SLIDE, 1996: 57). That is why she also performed as lead actress in her first films, usually embodying the housewife with nineteenth century roots. Researcher Louise Heck-Rabi (1984: 56) assures that, in 1914, Lois Weber was more popular as an actress than as a director; and historian Anthony Slide (SLIDE, 1996: 59) states that in the year 1913, a critic of the magazine The Moving Picture World praised Weber’s performance of a young matron, claiming that her body irradiated domesticity. The director had started performing, in the year 1911, this role in marital plots and continued to embody it until 1917. When she stopped acting, she was prone to choosing similar figures to her: it is the case of Anita Stewart or Claire Windsor, two actresses that she discovered and made famous2, and with whom she continued to explore the complexity of female domesticity at the beginning of the century.

Who knows if the public’s identification of Weber as a housewife is what made the director decide not to perform in How Men Propose (1913), a short film in which the female character does not want anything to do with domestic life: she pretends to be interested in three gentlemen who, one by one, declare their love for her; afterwards, she promises them, individually, matrimony and even accepts an engagement ring (which she changes every time for her own portrait). In the end, she sends them a note thanking them for their help: now she will be able to write an article on how men propose. The film is a very well constructed joke in which the viewer can see the very similar reactions of the three gentlemen –firstly of nervousness, then of happiness–, while her body language increases in theatricality and sense of humor. Lois Weber, in spite of using a comedial tone, does not ridicule or parody the female figure. The balance with which she manages to dignify the protagonist’s mischief has to do precisely with her rigorous appearance of a domestic woman, which hides the bright, emancipated girl. We could read the short film as a warning: a woman is never just what she seems.

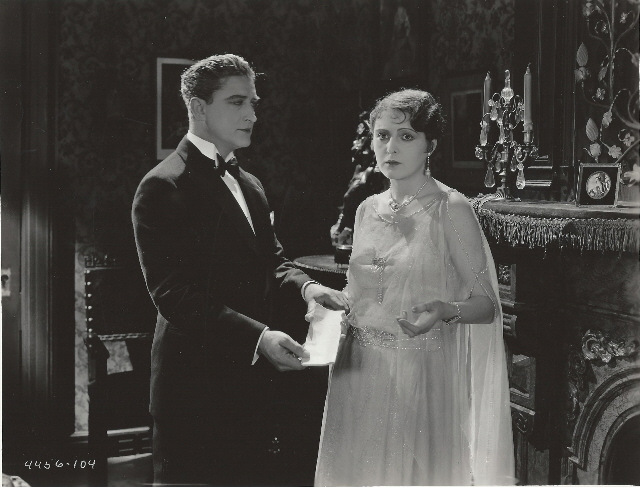

Indeed: Lois Weber, living between two eras, dedicated herself as an actress –and especially as a director– to explain the ambivalence that always gnaws in a feminine figure. In this sense, it is not strange that she performed in The Spider and her Web (1914, codirected with Phillips Smalley), a short film in which she embodies a vampire named Madame DuBarr, who destroys the heart –and savings– of the men she attracts malignly. One day, a scientist that wants to end the woman’s terrible power, makes her drink a potion to make her believe she is sick. Madame DuBarr, with the aim of straightening out her life, adopts an orphan child, but afterwards discovers the scientist’s scam, which makes her want to return to being her past vampire self; in the end, though, she realizes she cannot leave the child with whom she has established a deep intimate bond. More than moralizing about the maternal goods, Lois Weber explores how habits are retained: firstly, she shows how it is hard for the character to change her vampire habits and, afterwards, how it is hard for her to abandon her maternal feelings. This dialogue –and tension– between two ways of being a woman highlights the integration of opposites that a female body holds. Nancy F. Cott (1987) explains, from the historical context of the first decade of the century, that the change of century opposed two generations—the older generation with nineteenth century habits and the younger one with new modern proclamations. But as Karen Ward Mahar explains further (2006: 91), some women, on and off screen, retained habits from the past while embracing the freedoms of the New Woman. Lois Weber is a good example of this: on screen she irradiated domesticity while she was, indisputably, a modern woman who triumphed as an actress and director. In real life, she revealed that she believed in marriage: ‘There is no doubt that marriage is the most important event in our lives and the least studied or understood’ (WEBER in SLIDE, 1996: 16). According to historian Anthony Slide, the relationship between Lois Weber and her husband Phillips Smalley had started to establish itself in a very Victorian manner: during the first two years of marriage, she did not work and stayed home while her husband travelled as a theatre producer. Afterwards, Weber rebuilt her life as an actress, wrote scripts and started to make films with Smalley, but he ended up becoming jealous of his wife’s triumphs: Slide details that the 1914 reporters wrote about Weber’s creative importance in the films that they signed together (SLIDE, 1996: 30). And, still, Lois Weber continued to worry about being a good wife, as we can see in her later statements and the films she made, where the main characters, as I will develop later on, struggled between a domestic life and a more autonomous one. This interest in evoking in her films issues that were related to her own personal life is revealed in a more open way in The Marriage Clause (1926), ¡a semi-autobiographical examination’ (SLIDE, 1996: 29) of the first years of her marriage which she made four years after her divorce to Smalley. In summary: Lois Weber was a woman that, from her Victorian moralism, started to follow some of the recent standards of modernity, but made visible the tension that implied coexisting with these two ways of thinking; she used the camera to capture what she was experimenting and, through her female characters, was able to fix her thinking in movement.

2. The moral Truth of a female body

Sincerely, Lois Weber, signed the director on a photograph of her figure at the beginning of the film Hypocrites (1915), a film that she directed by herself and was considered her artistic milestone. It is a moral fable in which Lois Weber criticizes the hypocrisy of politicians, businessmen and lovers of the new century, through the medieval gaze of a preacher, where a minister fails to make the Naked Truth known to the community, a symbolic figure that everyone misunderstands because it appears completely naked. Lois Weber’s boldness of allowing a naked woman on screen –that even showed her body frontally– stirred the censorship. Hypocrites became a scandal wherever it was shown (Boston’s mayor demanded to dress the symbol of Truth, requesting to paint the frames where the naked character appeared), but, in the end, it became a public and critic success. Lois Weber did not perform the Naked Truth. Probably she did not dare to show herself naked, but the truth is that some magazine wrote that Lois Weber had dared to perform in the film the naked symbol of the Truth (HECK-RABI: 56). And, in fact, they weren’t completely wrong: Hypocrites can be understood as a personal manifestation of how she wanted to treat the female body on screen: far from wanting to give it a sexual sense –but using the erotic power of a naked female– she translated the sensuality of a body into a moral concept, into a space of reflection.

Lois Weber had worked as a social activist in the streets in the name of the Evangelical church; thus, she knew the importance of reaching the people and she tried to make her cinema a piece of reality, a means of shaking the public, to morally educate viewers. In the first decade of the century and especially during the years of the First World War, Weber, as Richard Koszarski (KOSZARSKI: 140) states, ‘reached an enormous success combining an astute commercial sense with a rare vision of cinema as a moral instrument.’ In fact, when Hollywood wanted to legitimize the cinematic spectacle, amongst the bourgeoisie, it had to demonstrate that fictions could be something more than car chases or love stories: moral values emerged in David Wark Giffith and Cecil B. DeMille’s most prestigious productions, two directors that were competing with Lois Weber’s productions in the year 19153. The most popular actresses of the time such as Mary Pickford or Mabel Normand also ideologically took part in the films that they performed in and, off screen, declared themselves in favor of president Wilson’s interventionism, in patriotic speeches or by selling government bonds: on and off screen, these actresses asserted a clear moral conduct of how the American citizen should act. Researcher Veronica Pravadelli (PRAVADELLI: 2014, 107) claims that in that first decade:

‘Women were believed to be more suitable than men to promote cinema’s reputation, due to their alleged moral superiority. (…) Women could maintain the morality of the nation through a spiritual management of the private sphere, of the home and the family. This moral superiority has favored women’s determination outside the domestic space to battle social problems such as poverty, prostitution, slavery, alcoholism, etc. It is in this tradition that women are perceived as essential to the moral improvement of cinema (and of the nation)4.’

What I am interested in highlighting from the words of the Italian historian is that woman’s moral superiority embraced the sphere of reality; that is why, from the stars’ position –the case of Mary Pickford– or from cinematic creation, in Hollywood, women of the beginning of the century made themselves heard. It can’t be fortuitous that, in the film, the only two figures that understand the symbolic figure of the Truth are of the female sex: a woman –in love with the preacher– and a little girl. Thus, Lois Weber evoked the relevance of the (moral) female gaze; in the same way that she defended that the female body was more than just an object for the masculine gaze, she initiated a reflexive journey about female subjectivity.

3. The body/cinema as a space for reflection

A year later, Lois Weber directed Where Are My Children? (1916), a film, sixty-two minutes long, signed with Phillips Smalley, that revolves around abortion and birth control, from the gaze of different female characters. But Lois Weber focuses in the movement of Mrs. Walton’s thinking (Helen Riaume), a rich woman, married to a wealthy lawyer, that expresses the feelings that torment her, not so much for having aborted5, as, mostly, for not having told her husband. Lois Weber visualizes the reflective movements of this character, next to a husband who longs to have children, who plays with their neighbors’ children or watches, entranced, the children that surround him whereas Mrs. Walton does not show any maternal gestures towards them. One scene that stands out is when the couple welcomes the husband’s sister to their home, who has just had a baby, and while Mr. Walton lavishes looks and caresses on the baby, his wife does not show any emotion. Lois Weber does not ridicule Mrs. Walton’s attitude (but she doesn’t praise it either): the director constructs a female character that, in theory in a natural way, does not have a maternal vocation.

But her husband’s desire to have children makes her rethink her vocation. This is where Lois Weber focuses all her attention to express it cinematically. To reveal in images the thinking of the woman that shifts between conviction and doubt, the director shows Mrs. Walton walking around her room; after, she lowers her head, she ponders slightly moving her face; afterwards, she stand up firmly, as if she were making a new decision and, in the end, she sits down and smiles staring vacantly, convincing herself that she is able to please her husband. Her body language is not that different from the one I described at the beginning of the article, regarding the short film Suspense. And the idea is similar, because, in both cases, the purpose is to dramatize the intimate debate that the woman experiences when, in her mind, two in theory opposing logics arise: the one that belongs to the nineteenth century world and the one that responds to the century of woman’s emancipation. Lois Weber focuses on trying to capture cinematically the difficulty of joining them. Thus, the thinking in movement of her characters visualizes the attempt –and sometimes the failure– of synthesizing these two stereotypes, transforming the female body into a space for reflection.

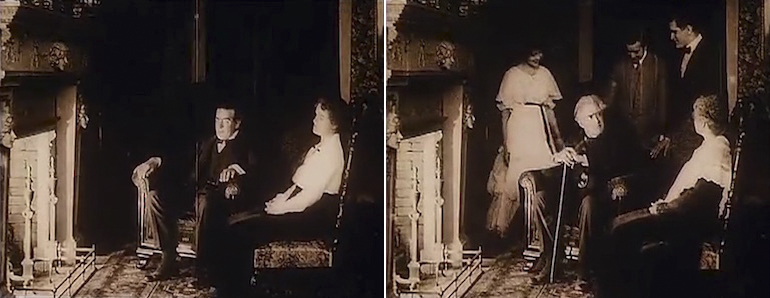

Against a conventional resolution, Lois Weber doesn’t make the main character of Where Are My Children? finally consent to being a mother, but inserts a narrative turnaround in which the couple cannot reconsider anything as a family: the husband discovers that she has concealed her abortion and cannot forgive her. The film ends with a scene in which the couple is sitting in front of a fireplace, in two different armchairs, without looking at each other, showing the isolation that has reigned between them during the years. Lois Weber superimposes the image of three children that play among the couple; a dissolve brings us, twenty years later, to the same framing, with both characters now old, swallowed by the solitude of their silence; the children from before are now three adult boys which, superimposed, surround the couple lovingly. Lois Weber, in this ending where she captures the thinking’s immobility, the disastrous density of the passing of time, catapults the film to a cinematic modernity without precedents: I am referring to the modernity of the time-images with which Deleuze describes the images that contain thinking, those where the action stops being the main character, so that temporality can emerge. Lois Weber had found modernity because she had explored feelings from the strictest realism.

Five years later, when her cinema started losing the public’s favor, the critics highlighted a film such as Two Wise Wives (1921) that did not have dramatic situations, there was no action, the heroines were not perfect, but, precisely for these reasons, it ‘seemed true and, more than that, quite likely’ (SLIDE, 1996: 117). In opposition to what the dream factory was offering, Lois Weber starts the film as if it were the ending of a classic movie to openly question the conventional ending of the Hollywood narrations: Two Wise Wives opens with a sign that reads: ‘Most stories end: “And they lived happily ever after”’ and, subsequently, it shows a couple that is walking towards a lookout, while the sun is setting. The own Lois Weber had said: ‘I was tired of unrealistic happy endings’ (MAHAR, 2006: 141). After reproducing this conventional happy ending at the beginning of her film, the director tries what classic Hollywood had always concealed: visualize what could happen after the Happy Ending.

Two Wise Wives presents the story of a couple in which the wife (Marie Graham, performed by Claire Windsor) is jealously looking after the household and trying to please her husband until a more modern woman (Sara Dely, embodied by actress Mona Lisa), also married but not focused on her husband at all, tries to seduce the first woman’s husband. Lois Weber portrays these two females, as if they could not be part of the same body, but, however, shows the meeting points of union between them. And, in both cases, there is a criticism of both the domestic and modern woman. Precisely because of this Lois Weber’s final thesis is not clear: it is impossible to know with certainty which model of a woman does she finally stand for (and here it is important to bear in mind that the title equally describes both women: Two Wise Wives). In fact, I understand that the director deliberately does not choose any of the wise women, because what interested her was the transition that happens between them. Anthony Slide (SLIDE, 1996: 114) points out that, at the end of the film, the main characters will have learned from each other: Sara will treat her husband better and Marie will not be solely focus on hers. Again, Lois Weber becomes an extraordinary filmmaker showing the protagonists’ feelings that, with their differences, make up the two worlds of the female reality of the beginning of the century. Lois Weber’s cinema tries to transgress the positive-negative, active-passive or housewife-emancipated woman duality, because, in her films, there is a visible research for synthesis, to put into dialogue –without opposing them– the new modern woman of the new century with the domestic femininity of Victorian roots. And this is finally her moral: a moral that obliges the viewer to think thoroughly, beyond the Cartesian structure of a binary thinking. And of course not everyone was willing to make that effort: as Karen Ward Mahar demonstrates, Cecil B. DeMille’s marriage comedies were having a great success in the same moment, as they were ‘pure entertainment’, whereas Lois Weber started to be harshly criticized for trying to ‘sell a moral’ (MAHAR, A2006: 148). A moral, yes, but open, not subject to a Manichean thinking, but to the contractile movement of reflection.

4. The synthetic subjectivity of femininity/of Lois Weber

The Blot (1921) was also disliked by the public, but the critics defended it: Lois Weber’s cinematic talent is so visible that it is considered her masterpiece even today6. Actress Claire Windsor embodied the leading role of Amelia Griggs, a girl who works as a librarian and belongs to a family with serious economic problems. The concise portrait that Lois Weber makes of poverty, in real settings with some non-professional actors, is of extreme concision (in this sense, the close-ups are always used to reveal objects which are worn, broken or full of holes, generating a very physic perception of poverty). The character of Amelia is captured, from the beginning, as a body that escapes immobility: introduced in a fixed way through a pencil drawing, the main character comes to life, making the drawing on her face disappear. Amelia begins moving slowly, as if Lois Weber wanted to remind us that, in her cinema, female action is resolved with small gestures that come from inner thoughts. Although having directed two movies, A Midnight Romance (1919) and Mary Regan (1919), where the female characters embodied heroic deeds along the same lines of the serial popular queens, Lois Weber, after the public failure of Mary Regan, went back to marriage and domestic films, maintaining her accurate study of the reflexive female inner being. We must bear in mind that, while the director was busy portraying this, Hollywood’s cinema, in the first decade of the century, constructed different female figurations to represent the new woman of the century of progress –chased naïve girls, melodramatic heroines, main characters of adventure serials or overwhelmed comedians–, all of them of an unstoppable external movement. And at the beginning of the 20s, the new flapper had invaded the screen, the young, dynamic, hardworking and dancing girl. Lois Weber was not able to impose her reflexive art at the voracity in which the audience demanded action and entertainment films: her rhythm could not be heard and, slowly, she lost the favor of all the publics7.

It is fascinating, taking into account that Two Wise Wives had also not succeeded, that Lois Weber, with The Blot, continued to maintain her slow –and realistic– rhythms and built a female character such as Amelia Griggs, a woman with a static gesture (who spends long scenes lying on a sofa, resting from a fever that has left her weak, without energy). But Amelia is a hardworking, cult and refined woman who, even with her sickness, has a dense mental activity, worried about her family’s poverty. At the same time, the film talks about the love that a poor preacher and a rich man have for her. The fact that the mother tries to make her daughter choose the more well-off man is symptomatic to distinguish, once again, inside the female sphere, the nineteenth century tradition –that only thought of a good marriage– and the main character’s gaze which receives both men with affection but without clearly orienting her desire. The rich man’s character is in no way ridiculed or vulgarized: on the contrary, he is an honest, sensitive, open man who even becomes friends with the preacher. At the end of the film, Amelia gets engaged with the rich man, but, shortly afterwards, on the porch, in the last scene of the film, she reveals her feelings openly, with the minimum body language, but making clear and concise the movement of her thinking. Amelia watches as the preacher who she has just tenderly said goodbye to leaves; the poor man walks on a path and turns to the house that he just abandoned; she doesn’t seem to notice the distant masculine gaze and, in a close-up, folds inwardly, smiles, as if she were imagining a fantasy and, finally, looks upwards demonstrating that she is fulfilling her wish8. Her sigh links with a reverse angle shot of the preacher, who also sighs looking in the girl’s direction. But neither knows of the other’s longing.

In one of the most modern open endings9 of the history of cinema, without specifying what will happen next, violating the conventional Happy End of Hollywood’s classic cinema, Lois Weber inserts the boundless desire of a woman who conceives her happiness in a mental dimension, probably not corporeal at all, but who offers it freely by an intimate movement outwards. With this gesture, Amelia synthesizes Lois Weber’s way of writing, giving form to a female subjectivity of the beginning of the century that she retains corporeally, but that can be read interiorly. Amelia synthesizes, from the body of thought, the female habits of the nineteenth century tradition with the liberated cries of desire of the New Woman.

FOOTNOTES

1 / I think of the husband when he is driving home at top speed and the police follow him: this car chase is resolved in a single shot, by means of seeing the pursuers’ car through the rear view mirror. It is clear that Lois Weber was exploring the different ways of presenting parallel actions. Another example of a synthetic exploit can be seen in the way that Lois Weber uses the high-angle shot: firstly, we see, in a high-angle shot, how the maid leaves the key under the entrance mat and, afterwards, we see the burglar entering the household and, seen from the same high-angle viewpoint, discovering the key, right where the maid has left it.

2 / Other actresses that she discovered were Mary MacLaren, Mildred Harris and Esther Ralston, amongst others, and she also promoted Frances Marion’s scriptwriting career.

3 / In the year 1915 she was the most important director of Universal Studios, as popular as D.W. Griffith or Cecil B. DeMille, and in 1917 she created her own production company: Lois Weber Productions. See Annette Kuhn and Susannah Radstone (ed).

4 / For more information on the matter of female moral superiority, see the revealing study of Karen Ward Mahar (2006).

5 / There are many purely moral interpretations of this film by historians. Anthony Slide (SLIDE, 1996: 15) already claims that Lois Weber’s work has not been very studied, even by feminists that have not learned to value the director’s cinematic talent, refusing the moralism or the not too radical portrait that she made of the female figuration. Veronica Pravadelli’s book is an exception: see p. 108-114 about the film Where Are My Children?

6 / A consideration that is based on the few films that can currently be watched. Slide calculates that Lois Weber made around forty films, apart from uncountable short films (about 100 IMDB seconds), but that only about twelve films have been preserved (SLIDE, 1996: 15). Furthermore, most of them are found in archives or libraries and not all of them can be completely viewed: some are missing reels.

7 / After this film, Lois Weber only directed seven more. The last one with sound: White Heat, 1934, in which she addressed the topic of interracial love. She had so many problems with the Hays Code censorship that the film was not even distributed.

8 / To understand which gesture I am referring to: BOU in SEGARRA: 71.

9 / The open (and modern) ending in realistic exploration films can be found, thoroughly discussed, in later films such as Stroheim’s Greed (1924) or Murnau’s Tabu (1931). And, obviously, Chaplin’s City Lights (1931) a film that also ends with a reverse angle shot.

ABSTRACT

Lois Weber, as an actress and filmmaker, portrayed in her films the tension that, in the beginning of the 20th century, women who wanted to maintain some of the Victorian traditions while listening to the New Woman empowering speeches experimented. Lois Weber was able to illustrate the appearance of a new female psychology by visualizing in a complex and conflicting way the difficulty of becoming a woman in the era of progress. The article, based on the analysis of some of her female characters’ body language, reveals the way in which the filmmaker gave form to the inner thinking of her characters on screen, defending the importance of the (moral) female gaze, realistically –and with an emerging modernity– exploring the construction of a female subjectivity that was pure thinking in movement.

KEYWORDS

Body, thinking in images, actress, woman filmmaker, female subjectivity, silent film, modernity.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOU, Núria (2007). Cuestiones sobre la representación del deseo femenino en la historia del cine. SEGARRA, Marta, Políticas del deseo, Literatura y cine, Barcelona (71-94). Barcelona: Icaria.

COTT, Nancy F. (1987). The grounding of modern feminism. New Haven Conn. Yale University Press.

HECK-RABI, Louise (1984). Women Filmmakers: A Critical Reception. Metchen, New Jersey. The Scarecrow press.

KOSZARSKI, Richard (1975), The Years Have Not Been Kind to Lois Weber. Village Voice, novembre 10, 140.

KUHN, Annette and RADSTONE, Susannah (ed) (1990). Women in Film. An international Guide. New York. Fawcett Columbine.

MAHAR, Karen Ward (2006). Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood. Baltimore. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

PRAVADELLI, Veronica (2014). Le donne del cinema. Dive, registe, spettatrici. Roma. Laterza.

SLIDE, Anthony (1996). Lois Weber. The Director Who Lost Her Way in History. Westport, Connecticut. Greenwood Press.

NÚRIA BOU

Núria Bou (Barcelona, 1967) is a professor in the Communications Department of the Universitat Pompeu Fabra and the director of the Contemporary Film and Audiovisual Studies Master’s Degree. She is author of La mirada en el temps (1996), Plano/Contraplano (2002) and Deeses i tombes (2004). Her lines of research are the star in classic cinema and the representation of female desire (Les dives: mites i celebritats [2007], Políticas del deseo [2007], Las metamorfosis del deseo [2010], La modernidad desde el clasicismo: El cuerpo de Dietrich en las películas de von Sternberg [2015], amongst other book chapters or articles). She is currently the lead researcher in the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness’ R&D project El cuerpo erótico de la actriz bajo los fascismos: España, Italia y Alemania (1939-1945).

Nº 8 PORTRAIT AS AN ACTRESS, SELF-PORTRAIT AS A FILMMAKER

Editorial. Portrait as an actress, self-portrait as a filmmaker

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

About the femenine

Maya Deren

About Fuses

Carolee Schneemann

Conversation about Wanda by Barbara Loden

Marguerite Duras and Elia Kazan

About the Film-Diary

Anne-Charlotte Robertson

Nothing to say

Chantal Akerman

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

About the Women Film Pioneers Project

Alejandra Rosenberg

Medeas. Interview with María Ruido

Palma Lombardo

VIDEO ESSAY

Florencia Aliberti, Caterina Cuadros and Gala Hernández

ARTICLES

Lois Weber: the female thinking in movementWeber: the female thinking in movement

Núria Bou

‘One must at least begin with the body feeling’: Dance as filmmaking in Maya Deren’s choreocinema

Elinor Cleghorn

Nothing of the Sort: Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970)

Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin

The Trouble with Lupino

Amelie Hastie

Presence (appearance and disappearance) of two Belgian filmmakers

Imma Merino

Identity self-portraits of a filmic gaze. From absence to (multi)presence: Duras,Akerman, Varda

Lourdes Monterrubio Ibáñez

REVIEW

Jorge Oter; Santos Zunzunegui (Eds.) José Julián Bakedano: Sin pausa / Jose Julian Bakedano: Etenik gabe

María Soliña Barreiro