A COMBATIVE CINEMA WITH THE PEOPLE. INTERVIEW WITH BOLIVIAN FILMMAKER JORGE SANJINÉS

Cristina Alvares Beskow

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / INTERVIEW / FOOTNOTES / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / INTERVIEW / FOOTNOTES / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jorge Sanjinés was the first film director to produce films in Aymara and Quechua in Bolivia. In a country composed in its majority by indigenous communities (Aymara, Quechua and Guarani), it is surprising that until the 1960s all films were in the language of the colonizer. Ukamau (1966) was the first Bolivian film in Aymara. The title means ‘It’s like this’, a word that later became the name of the filmmakers’ group founded by Sanjinés. Since then, the Ukamau Group has dedicated its films to the cultural and political resistance of the indigenous communities of Bolivia. Revolution (Revolución, 1963), directed by Sanjinés, can be seen as one of the seeds of this history. The short film was presented at the V Festival of Viña del Mar, Chile, in 1967. It coincided with the first meeting of Latin American filmmakers and the founding of the New Latin American Cinema movement, of which the filmmaker soon became one of the exponents. In 1968, at a meeting of documentarists in Mérida, Venezuela, Sanjinés stated that it was not enough to denounce, that it was necessary to make combat movies, to intervene in reality. Yawar Mallku (1969) and The Courage of the People (El coraje del pueblo, 1971) were made in the light of this notion, becoming true instruments of struggle. In 1979, he wrote Theory and Practice of a Cinema With the People (Teoría y práctica de un cine junto al pueblo), a work that has become a benchmark among political filmmakers. In time, Sanjinés has constructed a language of dialog with the indigenous culture, incorporating, for example, narrative elements that stress notions of community and circular time, like his famous ‘integral sequence shot’, present in Clandestine Nation (La nación clandestina, 1989). In 2012, the film Insurgents (Insurgentes) interacts directly with the new political situation in Bolivia, ruled for the first time by a president who defines himself as indigenous. In January 2013, I had the opportunity to watch the film at the Ukamau headquarters, in the city of La Paz, in a small and charming projection room. That same day, I interviewed Jorge Sanjinés. The conversation dealt with cinema and politics, focusing on the ideas of yesterday and today, and topics such as the collective character, the genocide of indigenous peoples and the cinema committed to the popular cause warmed up the cold evening of the Bolivian plateau.

Jorge Sanjinés: Even the French Revolution owes the indigenous. Some French intellectuals visited me and I asked them: ‘Do you believe that France and the French Revolution owe something to the indigenous?’ They looked each other as saying: ‘What is this crazy man asking us?’ I told them the story of the theater play The wild Harlequin and Rousseau. The wild Harlequin is a play that was written in the 18th century and was seen in Paris by Rousseau, who was quite young. In this work the playwright1, who had lived with the Iroquois Indians, reflected the ideas of liberty, equality and fraternity that they practiced daily… The Iroquois society was cohesive, articulated and carried out without State and without private ownership, with impressive spaces of individual freedom, spaces of freedom that the Europeans did not know because they came from the Middle Ages, even from the Renaissance. At that time, people had very little libertarian spaces, were cornered by the prejudice, by religious pressure, by the absolutist monarchies that used their bodies for the wars, and women, mainly, had no role, were censored, while the Iroquois gave them the same place as men and the Iroquois constitution rejected slavery. That is to say that the indigenous people were ideologically more developed than the Europeans and that is not taken into account. The ideas of liberty, equality and fraternity that appear in this play, The wild Harlequin, were seen in Paris by Rousseau, who hurried to write The social contract, the French Revolution bible. ‘Then, Gentlemen’, I was telling the French, ‘you see how you owe so much to the indigenous and do not know about it’. In Bolivia, the greater part of the white Mestizo ruling society is a society that coexists with the indigenous (now, reluctantly, because it feels like out of power), but they don’t know them and have always despised them due to ignorance and race prejudice: everything from the indigenous was not useful, was not worthy, was not important to know. Prejudices that have prevailed in the dominant collective memory to justify exploitation and genocide. In Brazil, it is the same. How can we kill the indigenous easily? This is the same as telling the people that the indigenous are not useful, are a nuisance, are people that have no value.

I think that we can start with your latest movie. Your movies are always inspired by the resistance of the people, especially the indigenous people, and now we have an indigenous in the presidency. Could you talk about the challenges of a militant cinema with the aristocracy of today in comparison with the aristocracy of yesterday, as you show in the film?

There is a very interesting sociological phenomenon that came about with the electoral triumph of the Aymara Evo Morales. In the first place, most of the ruling class that lost the elections in the year 2005 was completely convinced that this indigenous would not last three months in power, because he was an indigenous, an incapable person that by avatars of the democratic game suddenly pulled out more votes than them and was elected president. Very calm, they were very calm: I spoke with several of them to know what they thought and they told me that they were completely reassured, certain that it was going to be a total failure and it would be necessary to call for new elections. Not now, now they are perplexed, because Bolivia has never been economically better than today. We are almost the one that grows the most among Latin American countries: we are growing faster than Brazil, more than Argentina, more than Chile, more than Uruguay. After many years, dozens of years, we have a government that loves this country, who respects this country, who does not come into power to steal. Because before the government and the power were seen as places to enrich oneself personally. They used to take the power but were not thinking ‘we are going to enhance our country, we are going to improve it’, but ‘how I am going to get rich now that I have the chance to come to power, and the sooner the better’; and those who did not think like that had to do it anyway, representing a social class which coerced and pressured them to take such a measure, to appoint certain people. Then it was like the model in the United States: the ruler was a kind of puppet of dominant power with little space for his own initiative. And when you came out of that social control it may happen what happened to Villarruel, who, being a mestizo with a white skin, was identified with the indigenous destiny and said ‘No!’. I know that from very close by, because my father was a very close friend of President Villarruel: he was a senior economist and Villarruel asked him for advice on a project of radical agrarian reform, which I believe was the real reason why they killed him. He was not the only one. What happened to General Torres when he took the side of the people? What happened to him? He was killed in a street in Buenos Aires. So, the confusion the ruling class feels when faced with the irruption of the indigenous is very complex, because they are realizing that every day they are losing a bit more of that space, that political territory where they lived and ruled before, and were masters of. Every time we have in Bolivia more authorities of indigenous origin, indigenous who are taking up political responsibilities, ministers who are women from popular associations, or an indigenous governor, an indigenous president, a mayor of indigenous origin, and they do not like it, they are very angry. This is not a novelty; they were always angry with the country and have passed on that anger to their children. I recall a boy of 12 years at the airport who said to his father, ‘Dad, at last we are leaving this shitty country!’. A 12-year-old child. Where did this little boy of 12 years learn that this is a shitty country? From his father, his family, his environment. Then there is a panic in Bolivian society with the irruption of an Aymara, not because it is an Aymara, but because it is a process that has emerged. I hope nothing bad happens, but if tomorrow something happens to President Evo Morales, I believe that what would happen in other countries such as Venezuela, where the death of the leader can mean the end of the political process, would not happen here. Not here, here it is irreversible: if tomorrow Evo Morales fails, he can be replaced. The indigenous will retrieve the power and will not let it go, because this struggle, as shown in the film Insurgents, comes from very far back, very far: the idea of recovering the lost sovereignty has been permanently on their minds, of course, because they know that they are the majority, the 62-63% of the population, and have every right to manage their country, its territory. This process is very interesting, because I do not know if those who exercise power, even indigenous, are fully aware of what it means to regain power on the basis of the ideological and philosophical principles of indigenous culture, which is the most precious thing in the Bolivian process: the philosophy of a society that has prioritized the us over the I. That is the big difference, what has made October 2003 possible, without a leader, without a political party, because the ‘us’ acts as a collective entity. It is like the birds, which coordinate all at the same time and seem a single agency when they fly, because all of them know at what point they have to turn or move forward, and the picture is always the same. Indigenous cultures have preserved this, that sense of action, collective belonging. It is very difficult to understand this phenomenon, because, as we have been educated, or deformed, in western culture, we think ‘I first, I, before the others’. And to take this leap is the great challenge of this process for politicians who managed the country, because most of them have been educated in the individualism culture and often act that way without realizing that they are fighting with the ideology that should guide their steps, the ideology of those majorities who think ‘first us, then I’.

The Ukamau Group arose in the 1960s. What were the principles of its creation?

Well, before anything else, the interest to participate in the process of transformation of Bolivian society, that still was taking place as a result of the revolution in the year 1952. At that time, it had transformed the structures of a semi-feudal country into a bourgeois democratic country. This transit was generating new political and sociological expectations. The young people of that time were still very impressed by the processes of the revolution of 1952, positively impressed, although we were also critical with regard to what that process had failed to achieve, what it had betrayed. But we thought we were opening up revolutionary possibilities, particularly because the Cuban Revolution had triumphed. It was the Cuban Revolution which we felt soulful for: a country so close to the enemy, to the empire, that was liberated. Then it seemed to us that the liberation of our country was just around the corner, that it was a matter of organizing and fighting. At that time, we thought and believed in the armed struggle, as all the revolutionary world, because it was the only alternative in view, and also an alternative that had triumphed. Therefore, we believe our work of filmmakers was a work of political militancy: we did not see the cinema as the place for our personal realization, but as a place to make the country, to contribute with our work to create greater awareness in the dominated society, with the cinema as an instrument of struggle.

In that period, the cinematographic movement New Latin American Cinema was also created. How was the participation of the Ukamau Group?

Well, the first surprise we had was when our movie Revolution, a small documentary, a short experimental film, was presented at the VI Viña del Mar Festival, in the year 1967. We didn’t go, but the film did and had a good impact. There, the jury included the famous documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens, who loved the movie and took it for submission in the Leipzig Festival, where it won the grand prize. And then, we were told that in this festival there were several filmmakers who were making political films; not many, but some. Then, immediately, the following year, came to Bolivia Carlos Rebolledo, to invite us to attend the Latin American Cinema meeting organized by the Department of Cinema at the University of Mérida, Venezuela. And there we understood that we were living an extremely important process, because we discovered that several Cuban, Brazilian, Peruvian, Colombian, Venezuelan… filmmakers were working on a cinema committed to popular cause. Like the Brazilians, with Glauber Rocha looking for a cinema with a Brazilian identity, or like the ‘Third Cinema’ with Getino and Solanas; it was a big ideological party from the joy of finding other Latin American filmmakers displaying the same concern, with the same political project against imperialism. In Mérida, I improvised a small speech, like other filmmakers; I didn’t know what I was going to say, but our films Revolution and Ukamau created a very interesting climate and I was asked to speak2.

What was the impact of that speech?

Very good, because you see, it has been more than forty years since then, and throughout the subsequent process we tried to be consistent with those words, with that ideological postulate that we were already advancing. And because of that, the next film was precisely The Blood of Condor (Yawar Mallku), which is the complaint against sterilization without consultation of peasant women.

That film had a great political impact.

Huge, huge. Until then, I was also in agreement that a movie does not make history, but that film, yes, changed history, because of what it led to… First there was a shock, because nobody could believe that the good and friendly and noble gringuitos, all the peace corps sent by Kennedy, the nice one, could do what they were doing. No one could believe they were sterilizing peasant women in a country with low population, with a high rate of infant and maternal mortality. What was that? Then it was easy to accept that it seemed a diabolical lie, a slander, and it triggered a controversy in Bolivian society and several articles were published, some in favor and some against. The Congress of the country and the University appointed commissions to investigate the facts. After a few months, almost at the same time, the two commissions assured that what the film was denouncing was true and that they had several tests, testimonies and documents. That helped the Bolivian government of General Torres to expel the peace corps from Bolivia, as did Evo with the DEA3. It was a good blow in the snout of the empire (laughter).

... as a result of a political film. In addition, your movies had an educational role in the exhibitions and in the debates. In the manifest Toward a Third Cinema (Hacia un tercer cine, 1969), Getino and Solanas say that the revolutionary cinema has the role of discussing politics together with the people and think on action. How was the process of producing and exhibiting the Ukamau films here in Bolivia?

Exactly. We realized that it was not enough to make the films, because the films could be very revolutionary but if they served to win prizes at festivals or to impress the people of the cities, they were contradicting their objective. Therefore, we set up a system of dissemination: while preparing another movie, all of us that were part of the Ukamau Group would advertise the films in the factories, in schools, in the countryside, in mines… For 18 years, we have done this work to bring our cinema to remote places of the country. It has been a process of great enrichment because we have learned a lot, as we learned with Yawar Mallku when we made the film and we understood for the first time that the indigenous people had a culture that was not individualistic, that they were organized around the idea of democratic power, which goes from the bottom up; we lived it in the flesh. We realized that the individual protagonist did not make sense in the Quechua or Aymara indigenous community and that we had to achieve a collective protagonist, that is what we have in The Courage of the People. We have a single protagonist in The Clandestine Nation, but it is premeditated, because that individual actor lives and dies to be integrated into the collective: the true protagonist of the film is the collective, and Sebastián tries to redeem himself in order to be part of it.

How was that process of thinking a political and militant aesthetics?

This question is important, because we also realized that if the film had as objective to reach the greatest number of Bolivian viewers, it had to be built according to the precepts inspired by the internal mechanisms of another vision of the world, the vision of the majority, the vision of indigenous cultures. And we were developing our own aesthetics, a language, a narrative that was to culminate later in Clandestine Nation, where we built the ‘integral sequence shot’, which is a way of showing an interpretation of the sense of circular time of the Andean world. Among the Aymara and Quechua, time is not linear, as with the Europeans, it does not respond to the Cartesian logic. A space where the time goes round and everything will be back, that is what makes the camera narration in each sequence.

Facing the future, the past is in front of us, isn’t it?

Of course, the Aymaras understand it, so that the future is not always forward, it can be rearward, as shown quietly in the film. The last shot shows the burial of Sebastián, who has died in the dance of death, the body passes on and, when the camera returns without cuts, the last person following the funeral procession is him; but it is Sebastián reborn, he is the future, the future is back, facing the past ahead.

How did that develop into the ‘integral sequence shot’?

We were looking for a shot where the protagonist was collective, a shot that could integrate all and that disregarded the close-up, which is characteristic of European language, where individuality is exalted. It is not that in Clandestine Nation we don’t have close-ups, we do, but not by cutting, because we arrived at them in a natural movement with the camera, integrating everybody in the movement. That was crucial, because this shot comes from the way the indigenous people themselves tell stories.

I would like to know your influences in this process. In Ukamau, I see some influence of the soviet cinema and in The Courage of the People, I see something from the Italian Neo-Realism.

It is possible, but in the case of The Courage of the People it was not a premeditated thing, it was not that we watched Bicycle Thieves (Ladri di biciclette, Vittorio De Sica, 1948) and then we decided to make a film like that. The positive influences and also the negative ones are settled in the minds of human beings, we are influenced by good things and bad things. And several times or many times, we are not very aware of that, we do something in a certain way and it seems original to us. And if we dig a little in the memory, we might discover that it comes from images that were very powerful, we were influenced by them at a given time and that settled unconsciously. The same thing with the Soviets. I have read the writings of Eisenstein and Kulechov, which were the first reference texts for my work, and surely their conceptions of the montage, the juxtaposition of elements to join two different concepts and give birth to a new one, penetrated powerfully, because we were precisely looking for a cinema without words, as Revolution. The same with Ukamau: Ukamau is a film that may well be understood without reading the subtitles, without speaking Aymara. That is something that we saw in the Festival of Marseille, where the directors of the festival were too afraid to screen it to the French public, and didn’t want to; I told them: ‘No, do not worry, that has already been thought, this film has to work with such public without subtitles’. And they were encouraged and released the film, there was a nice debate, no one from the public asked ‘why it is not subtitled?’. They were not interested in that; it was not necessary.

How was the reception of the films in the communities?

One of the first films, Yawar Mallku, which was made to alert the indigenous of that act of criminal sterilization, didn’t work very well; not because they didn’t understand it (it was understood despite the fact that it is not linear and has flashbacks); what they all surely missed was the presence of the collective, because the film was focused on the individual. On the other hand, when we did The Courage of the People, the reception changed, the perception of the exhibitions was much more intense, and even more in Clandestine Nation. When we showed Clandestine Nation in the Cinemateca, Beatriz4 interviewed people and many asked her: ‘And why does Sebastián appear again, wasn’t he already dead?’ They did not understand that game, don’t you think? That question was never asked in the popular bar in Lima, because the Aymara people who saw that reappearance thought it was very natural; this shows that we were matching the cultural codes of the Aymaras.

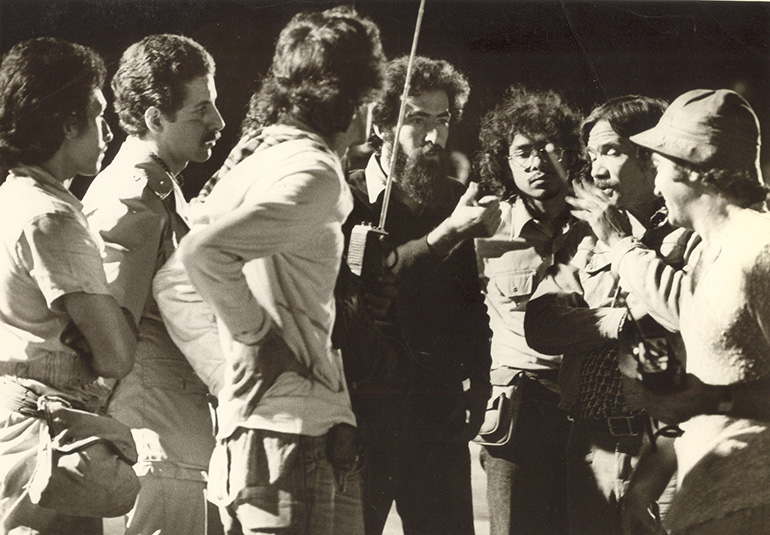

Your films are political already in the production process. So, how was the team work and the relationship with the communities?

First, it was necessary to fight the economic issue because, in the past, when we started, it was much more expensive to make movies than it is today. Ukamau was filmed in 35mm, we used a 35mm silent camera that was very large, very heavy, we needed 14 large battery packs to power it, the sound equipment used a perforated magnetic tape, everything was very expensive. We were able to do so because the state stepped in, but when we worked in Yawar Mallku we had serious economic problems, because we no longer had the support of the State, we were ‘us’ and nobody else. We had a tiny budget of $300 to film, which is like $1000 now, more or less, a camera with a single 35mm lens, and it was noisy, and we had no recorder… and used a rubber check (laughter). A rubber check, and there was a very strong argument among the team about that. Some companions, Soria for example, were very frightened because we were going to end up in jail. Then an idea occurred to me and I said: ‘Well, we can leave the prison, with security we are going to be able to leave it at some point, but we will never leave behind the frustration of not making the film. So, we do it!’ And so we did, and later faced enormous problems. I remember that when shooting ended in the Cata’s community we still didn’t have the money to pay the staff; the producer, who was Ricardo5, had made several trips to La Paz and had not been able to raise funds. On 30 December, with all friends wanting to return to celebrate New Year’s Eve with their families, I told them: ‘No, I will not go, I cannot leave because we are going to leave like always, we are going to repeat what they do, what whites and mestizos in society do, we use the indigenous people and then we disappear, no! Then I’m going to stay as a hostage, I cannot move from this community until you return from La Paz with the money to pay the people’. And one of the companions, an assistant, told me: ‘I am not going to leave Jorge alone, I’m going to stay’. We stayed, and almost died. Almost died because on the 31st they held a tremendous party in the community, where everybody drank burning alcohol (laughter); they were unaffected by it, but it burned our tongues, it pulled out pieces of skin off our tongues. And we were so intoxicated that we slept on the floor, we had no strength even to walk to the cot, we could have died; the fact that we were very young saved us. Nor could we say no to the people, it was not that we like to drink a lot, but that came and... ‘companion, brother, brother’... with me, everyone wanted to toast with me, I had to drink with them all, with the collective. At that moment, the collective cost us dearly (laughter).

Was the team small?

It was small, very small. The team of Clandestine Nation was 12 people; in Insurgents, we were 84.

Was the script created collectively?

Yes. Well, it wasn’t written by everybody, we didn’t do this, because I do not believe in that. I believe that each creator has his or her specific field in the cinematographic work: the musician in his music, the photographer in his photography, the scriptwriter and director each in their field. Now, you can collaborate, you can observe, you can criticize, the work can be improved with interventions, and we have always done that. Alejandro6 knows about it very well, because he has intervened several times in the last film and with his wisdom has provided a number of very important things; so, if Alejandro hadn’t contributed, the film probably would have been worse than it is (laughter). Then we are always ready to listen and to respond to critical comments and advice from the team’s companions, for each one feels as participant and maker of the film. I also used to intervene in the photography and I told to Antonio Gino, for example: ‘Here, why are you lighting it this way? If you change your reflectors we will see that part better’, things like that; and Antonio told me: ‘you are right’, and he changed it, and we all felt like we were doing everything. That was important and it has always been like that.

Some cinema groups, like the Argentinian Grupo Cine de la Base, which Raymundo Gleyzer was part of, had a very strong relationship with revolutionary organizations... Was your cinema also in contact with organizations here?

No, for a very simple reason: the Bolivian left was, I believe that it still is, a very small left, a left made of rulers, that has not been cured of this ruler behavior in their relationship with the indigenous. That’s why they despised the work we developed with the indigenous. I recall a discussion with a great intellectual, that I am not going to name to preserve his image, a great man, a very intelligent man, who said to me: ‘No, you’re wrong, you all are wrong: it’s wrong to exalt the culture of the indigenous people, we have to take the indigenous as proletarians, we must make them revolutionaries. Leave their traditions, they are things from the past, which harm them. They are petit bourgeois and land owners and we have to incorporate them and turn them into revolutionaries’. A great leader of the Bolivian left. How could we have relationship with people who thought like that? And that’s why they have failed, they have never understood their own country, because they are racists, deep down they are racists.

How was the production process? Did your movies have direct relationship with the indigenous movement?

More than with the movement, with the communities directly, with the Miner Unions, for example. The Courage of the People was done this way, it could not have been done differently, and therefore they participated in the film in a creative way. How could we tell Domitila Chungara7 ‘you have to say this’? How? It was impossible! We had to listen what she had said, respect what she had to say and say: ‘Well, we are going to do it again’. Nothing more. And the involvement of the Miner Unions was decisive: without their support, the militant support, we would not have made the film. They protected us in many ways, because it was very dangerous to work there. At that time, the Siglo XX Mine was controlled by the Ranger8, which was ruled by Siles9, who had just murdered Che and all that. If such people had discovered us carrying arms and military clothing in the middle of the night, we would have been killed directly. We did it just because we had the protection of the population; they would warn us, come running and say: ‘The army is coming’. Then, we would all hide the arms and get into the houses, let the patrols pass. This way, The Courage of the People was made, and it was made very fast: from the moment I went to write the script during two weeks in Yungas, until the film premiered in the Pesaro Film Festival, 4 months passed. A film with two and a half hours of duration when it was all finished, with thousands of extras and with pyrotechnics, with effects, with reconstructions of the war. I still don’t know how we were able to do it, because today, if I thought to produce a film like that, I would say, at least, a year, we could not do it sooner.

And what was the impact of that film in that period?

In Bolivia, it premiered seven years later, in the year 78. It was very strong, I think… The military were still in power and the film stayed for a week in the theaters, but when it started hitting society, the film was cut and censored. Before, two days after the premiere, as the film accused the commander of the army, General Arce, it was published in the newspaper a note saying that everything that slanderous movie said about the army was a lie, slanders from a terrorist group called Ukamau Group, and requiring the director of that group to issue a public retract. The next day, in the same newspaper, we presented our answer to the army commander: ‘General Arce, we cannot retract the truth, and if you threaten us with a civil-military trial we are fully prepared to attend, because such a trial will give us the opportunity to disclose to the Bolivian society a series of documents and testimonies that we have not had time to put on film’ (laughter). And that’s how it all ended, the army commander kept quiet, and shortly after, the film returned to the theaters.

Did you have other problems with repression by the dictatorship?

Yes, of course. Threats by phone, many times: that I was going to be killed, calling me a red bastard, that they were going to shut my mouth. After that, a place we had in Sopocachi was robbed, and they took films and documents. We were included in the list of people that had to be killed, we were in the third place alongside Luis Espinal10. We had to hide when going along the city, as we were being pursued by the military, we had to leave the country illegally, we stayed seven years in exile… it cost us dearly.

What changed in your films since the group started?

The cinema of Ukamau Group’s first stage is a cinema of direct confrontation, because at that time, for example, there was no television. When the events that inspired The Courage of the People happened in the year 1967, the newspaper only published a small piece about the massacre of San Juan, where three people had been killed in a scuffle between the police and some drunken miners. And nobody complained, nobody rectified that, no organization, not even the Miners Federation, nobody, nobody rectified that11. It was then that we made the decision to make The Courage of the People, because that had been barbaric. It was a memory that was being lost and there had been a massacre of people there, it was politically motivated, because of imperialism… and nobody said anything. So we made this film, because I was playing that role then: the cinema as an instrument to preserve a memory, because there was no other way. Then came the democratic process, and since then we have left the cinema of direct confrontation and have made films of greater depth, as in the case of Clandestine Nation and other films that touch on issues of identity or racism.

It is very interesting to think about how the militant cinema can join emotion and reflection.

Emotion and reflection, of course, that is the great challenge and the permanent concern of our work. That is why we have started making semi-documentaries or fiction documentaries, because we believe in that, and we have been able to see that a person who is moved thinks, can think better. Because when they leave the theater, if people are not moved, they forget what they have seen, but if they are moved, they spent one, two or three days thinking, reflecting on that and then recall images that have touched their hearts.

I have two more questions... The New Latin American Cinema was a very important movement for all Latin America cinema, not only for political films. For you, what are the consequences of this movement in the Latin American cinema?

Well, I think that the art of cinema, for its massive influence in societies, has been gradually building and strengthening our Latin American identity. At least in Buenos Aires, they used The Courage of the People and Yawar Mallku very intensely before the repression of 1976; those films, together with The Hour of the Furnaces (La hora de los hornos, Octavio Getino and Fernando E. Solanas, 1968) and Black God, White Devil (Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol, Glauber Rocha, 1964) circulated in the factories, in schools, in institutions. And nobody said ‘that Brazilian film’, or ‘that Bolivian film’. It was the film that was speaking to us, that was showing us our problems, which made us reflect on our liberation, and that contributed enormously to create what today the Latin Americans feel when we see Chávez sick. All Latin Americans with a revolutionary commitment must be concerned about Chávez’s life, because he’s not only the president of Venezuela, he is a leader in Latin America, of the great motherland, he has opened up new paths, he has created very important institutions that will strengthen the process that will become a reality when Latin America becomes a giant, powerful, brotherly homeland; because we have more reasons to unite than the Europeans. The Europeans have made a formal unity because, deep down, they feel great enmity toward each other: for example, talk to a Frenchman about a German or to a German about a Frenchman. As far as I’m concerned they keep hating, though they are now with the same currency for practical reasons. But we have that great advantage, we do not hate: we Latin Americans love each other, and that is a revolutionary change, it is an enormous advantage; it is going to be much easier for us to build a big and really very solid fatherland. We are working on that.

Regarding Ukamau Group, what is the difference between the militant cinema of the time when it was born and the militant cinema of today?

Of today? There is no difference, we are in the same dire straits (laughter), in the same adventure, aren’t we? And this is where we must continue, because the imperialism is also starting to disarm itself. What happens is that, when you put down a malignant giant like that, it brings along many misfortunes; we can still live very difficult and very dangerous times for the Latin American project, because the fall of the dominant system is inevitable, it is a self-destructive system in the way it exploits, it will burst. That’s fine. I’ve spoken too much.

Acknowledgments

Jorge Sanjinés, for the precious dialogue.

Alejandro Zárate Bladés, Flávio Galvão, Marília Franco, Rafael Pereira, Viviana Echávez and Yanet Aguilera, for the invaluable contribution.

FOOTNOTES

1 / Louis François Delisle de la Drevetière.

2 / The full speech can be read at: http://cinelatinoamericano.org/biblioteca/assets/docs/documento/497.pdf

3 / Drug Enforcement Administration (United States).

4 / Beatriz Palacios was a director and partner of Jorge Sanjinés.

5 / Ricardo Rada, which also was part of the Ukamau Group.

6 / Alejandro Zárate Bladés, who worked as assistant director for Sanjinés.

7 / Domitila Chungara was an important activist and worker leader of Bolivia. In 1967, she survived the massacre of San Juan, perpetrated by a military action of the government of René Barrientos against miners who fought for better working conditions. The massacre was reconstituted in the film The Courage of the People, with participation of the workers.

9 / Luis Adolfo Siles Salinas.

10 / Luis Espinal was a Jesuit priest, filmmaker and social communicator. During the decades of 1960 and 1970, he supported the struggles of the miners’ movements and fought against the dictatorship in Bolivia. In 1980, he was assassinated by the military.

11 / Dozens of miners were actually killed in the massacre.

ABSTRACT

Jorge Sanjinés was the first film director to produce films in Aymara and Quechua in Bolivia, a country formed mostly by indigenous communities (Aymara, Quechua and Guarani) that until the 1960s had only produced films in the language of the colonizer. In 2013, I had the opportunity to interview the Bolivian filmmaker in the city of La Paz, Bolivia. Sanjinés, who wrote the classic manifesto Theory and Practice of a Cinema With the People (1979), spoke for more than an hour on different topics, from the militant cinema of the 1960s and the 1970s to his current productions. In addition to making a reflection on the relevance of the ideas that he advocated in those years, he spoke of the process of production and exhibition of the films he did about struggle together with indigenous people.

KEYWORDS

Jorge Sanjinés, Bolivian film, Latin American Cinema, political film, militant cinema, New Latin American Cinema.

CRISTINA ALVARES BESKOW

Cristina Alvares Beskow is Doctor in Cinema by the School of Communications and Arts of the University of São Paulo (ECA-USP). Since 2008, she has worked with audiovisual productions, especially with documentaries. Currently, she is a member of the Group of Latin American Film Studies and Artistic Avant-garde (GECILAVA) and studies the Latin American cinema of the decades of 1960 and 1970.

No 9 EZTETYKA

Editorial. Eztetyka

Albert Elduque

DOCUMENTS

Revolution

Jorge Sanjinés

Tricontinental

Glauber Rocha

Godard by Solanas. Solanas by Godard

Jean-Luc Godard and Fernando Solanas

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

A combative cinema with the people. Interview with Bolivian filmmaker Jorge Sanjinés

Cristina Alvares Beskow

Conversation with Eryk Rocha: The legacy of the eternal

Carolina Sourdis (in collaboration with Andrés Pedraza)

The necessary amateur. Cinema, education and politics. Interview with Cezar Migliorin

Albert Elduque

ARTICLES

Reading Latin American Third Cinema manifestos today

Moira Fradinger

From imperfect to popular cinema

Maria Alzuguir Gutierrez

The return of the newsreel (2011-2016) in contemporary cinematic representations of the political event

Raquel Schefer

ImagiNation

José Carlos Avellar

REVIEW

TEN BRINK, Joram and OPPENHEIMER, Joshua (eds.) Killer Images. Documentary Film, Memory and the Performance of Violence

Bruno Hachero Hernández

MONTIEL, Alejandro; MORAL, Javier and CANET, Fernando (coord.) Javier Maqua: más que un cineasta. Volumes 1 and 2

Alan Salvadó Romero