A FRENCH ROMAN. A STORY ABOUT THE INFLUENCE OF SOVIET AVANT-GARDE ON CAHIERS DU CINÉMA AND THE LATER REDISCOVERY OF NICHOLAS RAY. AN INTERVIEW WITH BERNARD EISENSCHITZ

Fernando Ganzo

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

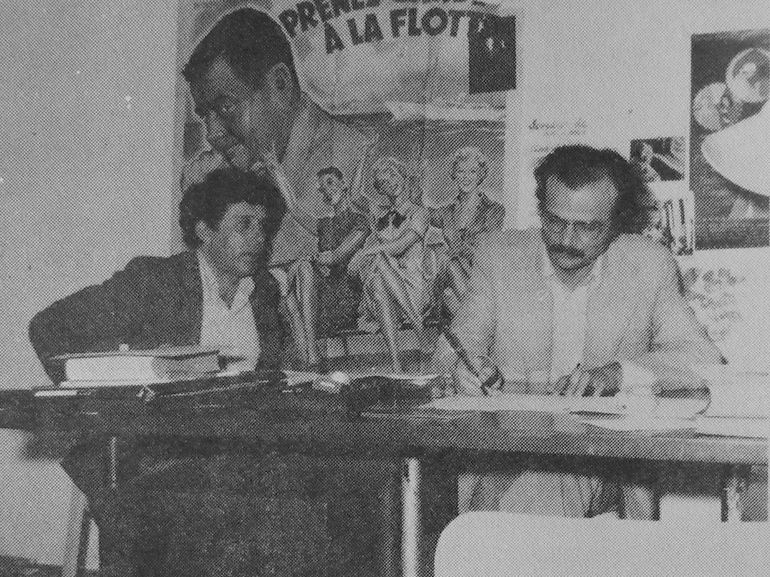

You belonged to Cahiers du cinema from 1967 until 1972, that is, during a period of great ideological turbulence in the magazine, with intense leanings towards Maoism and communism. After this, you were a member of La Nouvelle Critique, a magazine that was very close to the communist party, from 1970 until 1977. Most recently, you directed the magazine Cinéma from 2001 until 2007.

I had worked at Cahiers du cinema before that, in the period of the yellow Cahiers, on the special issue on American cinema, no. 150/151. That was over two or three months, at the end of 1963. At that time the magazine was directed by Jacques Rivette. When I joined the magazine later on, the team was not the same. That more definitive return took place in 1967, on the occasion of a trip to the UK: I visited the shooting of Accident (1967) by Joseph Losey. Then I started writing notes on the monthly premieres, which we all found a lot of fun, and then I joined the team; it was the moment of the ‘affaire Langlois’.

![[i]Masculin, fémenin: 15 faits précis[/i] (Jean-Luc Godard, 1966) img entrevistes eisenschitz02b](/cinemacomparativecinema/images/ccc02/img_entrevistes_eisenschitz02b.jpg)

Could you describe how you perceived the political and aesthetic developments during the period 1963–67, until you returned to Cahiers? How did that period become more turbulent and radicalised?

Radicalisation arrived later, in 1967. The film that best describes it is Masculin, féminin: 15 faits précis (Jean-Luc Godard, 1966). My political culture was inherited. Cinephilia was a way to break with that tradition, although you know that when you throw that political culture out of the window, it will come back through the door. These were years marked by the primitive accumulation of films, of cinephilia, marked by American cinema, with some bursts of rejection of the ‘New Cinemas’. Things precipitated. On the one hand, there were discoveries of forgettable – and in fact forgotten – American film-makers, who were disproportionately celebrated, as was the case with Don Weis and his film The Adventures of Hajji Baba (1954), very refined in terms of colour, as it was produced by Walter Wanger, but at the end of the day it wasn’t but an adventure film like any other. And on the other hand, we discovered, of course, the films of the Nouvelle Vague, and later on the so-called ‘national cinemas’, which we found fascinating. At the same time, there was a certain idea of superiority of American cinema, as it was a question of birth or divine right, while we kept on discovering things in other places. I am not sure whether it can be said that all of this crystallised at one specific time…

Perhaps it’s not a question of crystallisation, but rather the intuition that something was changing.

The films we saw at the Cinémathèque Française – even though they were many – didn’t signify this either. I thin in the presentations of the new films, Langlois’s friendly programmes, who showed the works of young film-makers, but we didn’t see great revelations in that sense. Langlois was reluctant – and by then we thought along these same lines – to the ‘new cinema’ and, in particular to all that was self conscious in cinema. On one occasion he made a well-known introduction of the New American Cinema in the presence of P. Adams Sitney, who was bringing the film cans. He said he disliked that cinema but that even so he thought it was important to show those films. Reading Cahiers, one can clearly perceive how it was hostile to the American underground. It wasn’t until 1970-–71 that those films were rediscovered, with great delay.

During that time I used to travel frequently to Italy: I was doing research for a book that I never wrote, but I also looked for the traces of a global talent in film production, and an ‘equality of rights’ in the films that could be compared to American cinema: Luchino Visconti at the same level as Ricardo Freda’s peplums; Hercules and the Conquest of Atlantis (Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide, Vittorio Cottafavi, 1961) had the same right to exist than Viva Italia! (Viva l'Italia, 1961) by Roberto Rossellini. I used to see the work of film-makers such as Cottafavi, Freda and Matarazzo. The communication between France and Italy was uneasy at the time, and Louis Marcorelles, the director of the Semaine de la critique at Cannes, asked me to suggest films that might be suitable to show there. I then saw Antes de la revolución (Prima della rivoluzione, Bernardo Bertolucci, 1964), which was for me, as well as for Cahiers a couple of years later, a true revelation. Hence, in Italy, one could find the most fascinating cinema in B movies, genre films, comedies, historical films, in peplums, and in action films. And at the same time Bertolucci and Pasolini were there, whose films I really liked since the beginning and whom I recommended to Langlois when he asked me to look for films for his museum. The situation of film in Italy was like a cross-fade or an overlayering. But the radicalization arrived to ‘national cinemas’ with the politicization, mostly in France. For a number of years, American cinema, and even cinema itself, was abandoned in favour of our political activities.

Were the dialogues and exchanges with other institutions usual, such as Godard’s visits to the university in 1968?

I didn’t follow those visits at all. Luckily, several members of Cahiers went to the university when there wasn’t an education of that sort and based their in their political positions of the time, which were certainly very radical, such as: ‘Whomever is not with us is against us.’ The dialogue was complicated and during two or three years I stopped talking with some of the members of the editorial team. But those who worked at the university were on the Maoist side of things. Meanwhile, in 1970, I worked at Unicité, an audio-visual communication company that belonged to the Communist Party. There I worked on the distribution of films, namely those that belonged to the archive of the party, a sort of ‘litter bin’, since it was there where the propaganda documentaries and feature films of (mostly) socialist countries sent their films. In that archive we sometimes found classics from former Eastern Europe or old French militant films; films that arrived there by chance, that had been produced by Unicité or that we commissioned from film-makers that were ideologically like-minded. Using that archive, I worked on a distribution strategy that was ‘militant’ and ‘commercial’ at the same time. In two or three years, I managed to premiere 5 or 6 films, some of them Soviet films, not necessarily political ones, and even some of them not even very ‘official’, such as Premiya (Sergei Mikaelyan, 1976), a huis clos often compared to 12 hombres sin piedad (12 Angry Men, Sidney Lumet, 1957). The film was about the internal structure of a factory, but was also a film that challenged the old methods by which power had been officialised: even if the successive governments of the USSR spoke of fighting against bureaucracy, pretending to fight against it, bureaucracy lived on generation after generation, since it was always the other’s fault, and one could always say ‘Down with bureaucracy!’ That film was very ambiguous and we wanted to ‘use’ it to show that things could still move in the USSR.

How is your work on the distribution of those films related to the special issue of Cahiers dedicated to Russian cinema of the 1920s (‘Russie années 20’, nº 220/221)? Could you narrate the sequence of events? What was the motivation or evolution of your critical thought during this period?

We lived in a strict community. I travelled to Moscow in 1969, but the decision to work on the Russian and Soviet avant-gardes came before then. Regarding the evolution and motivation to do this, it’s important to say that we weren’t the only ones interested in this period, since there was a very important previous step: at the end of 1967 Langlois organised a great retrospective of Soviet cinema, interrupted in February 1968 due to the ‘affaire Langlois’, which continued un July that year at the Festival d’Avignon. That edition of the festival was very politicised and was very turbulent, with many antagonistic events of all sorts. Langlois titled his season ‘Les inconnues du cinéma soviétique’, calling attention to the work of Boris Barnet. He also screened Dziga Vertov’s The Sixth Part of the World (Shestaya chast mira, 1926), which hadn’t been shown in the West since the 1930s, and had since been considered lost. He also showed us film-makers such as Yuli Raizman, thus encouraging us to work on that cinema and, on the other hand, from then we started to look for the writings of Sergei M. Eisenstein. Because of the opposition of the Bazinian tendency, these had largely been forgotten.

![[i]Shestaya chast mira[/i] (1926) img entrevistes eisenschitz03b](/cinemacomparativecinema/images/ccc02/img_entrevistes_eisenschitz03b.jpg)

With the impulse of that season, I travelled to the 1969 edition of the Moscow Festival with the aim of preparing the documentation for that issue. There I got in touch with Eisenstein’s studio, in order to publish his writings. Later, in 1971, Cahiers published a second special issue (nº 226-227) dedicated to Eisenstein with texts by Jean Narboni and Jacques Aumont, the only one able to translate Eisenstein’s writings into English. After leaving Cahiers, I carried on with this Project at La Nouvelle Critique, with several programmes on Soviet cinema, one of them Langlois’s programme at Avignon, which was then also shown at the Centre Georges Pompidou.

We are interested in that opposition between the Bazin and Eisenstein tendencies of understanding montage, that is: how could Eisenstein’s ideological montage be defended by a magazine whose ideological father defended the apparently opposed notion of montage? To what extent were those programmes and the special issue on Soviet cinema able to change the editorial line of the journal?

I never aimed to influence the editorial line. My position was that of an historian, not the one of an ideologue. Bazin’s idea, as the most important thinker and member of Cahiers, was never questioned, in the same way that it happened with Godard, Straub or Renoir. They were fixed references, much stronger than Hitchcock or Hawks. What they all had in common – perhaps except Bazin – was that they were all figures ‘against’ something. With only his presence, Renoir rendered ‘negative’ all the French ‘quality cinema’, and was hated for that. In the cases of Godard and Straub, it seems unnecessary to explain. But what is important to consider is that, by developing the ‘ideology of transparency’, the heirs of Bazin his ideas took to an extreme, in particular the ‘macmahonians’ and other admirers of American cinema – among which myself, to a certain extent. Bazin didn’t talk about this, but about a ‘window’ open to the world. It was the idea of an art that concealed its own traces, which was not noticeable. Such perversion – or radicalization – of Bazin’s idea, allowed rediscovering the work of any American film-maker who would have had enough with having his script filmed.

The Eisensteinan reaction against this idea was, actually, a political one. If you read the Jacques Lourcelles’s film dictionary – a magnificent book, as well as the summit of that ideology that comes from Bazin – you can notice that, as Daney said, that tendency is translated into a conservative thought. I am not saying that Lourcelles is politically conservative, but his form of thought is – he in fact considers himself apolitical, which is common amongst the conservatives. Lourcelles is very generous, on the other hand, and was very critical with the ‘black list’. In one of his last texts, in issue no. 3 of Trafic, Daney explains it very well (DANEY, 1995: 5-25). Art was ‘trapped’ in a political and historical movement, and could not get rid of it. It is not only a passive reflection, but also an instrument: films are an image of reality, but they can contribute to change it. Being somewhat utopian, it could ‘function’ politically. The reaction against the ideology of transparency aimed to politically revolutionise film thought. It may be that Eisenstein’s cinema wasn’t useful to understand the October Revolution, or that Vertov’s helped better to understand the situation, but that direction was justified insofar as it enabled spectators to better assimilate what it showed and its own dream; to make cinema based on that dream. Even if this idea wasn’t precisely formulated during that period, in Cahiers, more radically, once I had already left, they realised a somewhat absurd taxonomy dividing the films that passively reflected reality, even those that admirably did so (John Ford) and those that intervened in reality (Brecht or Eisenstein, I guess). It was a double editorial written by Jean Narboni and Jean-Louis Comolli, across issues 216 and 217, and titled ‘Cinéma/idéologie/critique’.

Which were the most influential points in taht rediscovery? At the time, people spoke of Eisenstein’s montage against Pudovkin’s montage.

They were Eisenstein and Vertov. To be entirely honest, I think that, at the time, in Cahiers they didn’t see Pudovkin’s films. He was considered as a sort of a placeholder, used as an example of a film-maker who hadn’t understood montage. But I think they didn’t see his films. They did see a bit of Kulechov, who wasn’t a great film-maker, but not Pudovkin. Therefore the discussion was fraught since the beginning.

It seems relatively easy to follow the traces of that will to ideologically shake the theory of montage, which arrives to its formal materialization in Two or Three Things I Know About Her (2 ou 3 choses que je sais d'elle, Jean-Luc Godard, 1967), which is a very Eisensteinian film.

Yes, but it is very difficult. I have never understood, not even after having spent six months reading Godard’s writings and his biographies, how he captured things about the cinema that were contradictory, and far from being obvious. How he knew, since he started to make cinema, so many things about Bazin’s open window to the world and at the same time about Eisenstein’s montage. How he was able to understand all the equations of cinema, to use Scott Fitzgerald’s expression in the beginning of The Last Tycoon (1941), if adapted to the idea of the ‘author’ in France. It is the delirium of a systematic poetic interpretation, for instance, of the critique of Bitter Victory (Nicholas Ray, 1956). How could he realise so early on that the two greatest editors were Eisenstein and Resnais, or to what extent Jean Rouch was fundamental for cinema? It is strange for someone to be so much ahead of his own time and peer group, something that was also the case with Jacques Rivette. Having understood this, Rohmer had chosen another form of making films. And Truffaut – generalisations are useless –, the more films he made, the better he understood the mechanism of American classical cinema and the more he knew about its culmination and nemesis: Hitchcock. If he had chosen Ford or Renoir, it would have been different, but he chose Hitchcock, heir of Kulechov, with his Anglo-American puritanism.

![[i]Bitter Victory[/i] (Nicolas Ray, 1956) img entrevistes eisenschitz04](/cinemacomparativecinema/images/ccc02/img_entrevistes_eisenschitz04.jpg)

What relationship did you have with Godard during the making of Histoire(s) du cinéma (1989)?

Soviet cinema was key here. In 1993 I wrote an article in Trafic, ‘Journal de Moscu’. I had attended the first retrospective of Boris Barnet, where I had the chance to see some films that had been considered lost or forbidden. At that time, Godard was preparing Les Enfants jouent à la Russie (1993) and read the text, where I state that the counter-shot didn’t exist in Russian cinema until the period of the Thawing, when they started watching American cinema. Before that, they did not have any theoretical or practical notion about the counter-shot. Godard was interested in this argument, and invited me to speak about it in the film, together with André S. Labarthe.

During the making of Histoire(s) du cinéma his only interlocutor was Daney. I visited him when the series was already finished, or at least the first two chapters were, which were determining for the rest of what was too come. He showed them to me and we talked about them, since we’ve always agreed on many things, but I was most closet o him when Gaumont decided to commercialise the series and asked Godard to submit a detailed index of all the fragments used. Godard said that he would never do any such thing, but that perhaps I could do. So, together with my partner, who is an archivist, we created an index of all the images, trying to remember all the films that appeared. Marie was in charge of the pictorial element. It wasn’t so difficult; I only had trouble identifying two or three images. Later on I travelled to Rolle to give him the index and ask him a few questions. We saw each other a few times only, doing a run throughHistoire(s) du cinéma, commenting each image. We looked for the cassettes or the recordings. In some cases, I worked as a detective, since Godard would only conserve a cut-out from an exhibition catalogue as the only document, for example, so that we had to follow some improbable clues. There were also fragments of porn films that Godard identified by country: ‘German porn’, ‘Russian porn’. With Daney, by contrast, he spoke so much about the project that he even included him in one of the episodes. I think that he showed him the beginning of the film and that the conversations started there, although only a little fragment is conserved in the film. As far as I am concerned, at the beginning I was too intimidated to be a true interlocutor. We had hardly seen each other during my time at Cahiers – in contrast with Narboni, with whom he had talked often and who even appeared in Two or Three Things. The Godard ideologue of the late 1960s scared me. Jean-Pierre Gorin or Romain Goupil, his colleagues at the time, seemed very arrogant and chauvinist, unlike Jean-Henri Roger, with whom he made British Sounds (Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Henri Roger, Groupe Dziga Vertov, 1969) and Pravda (Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Henri Roger, Paul Burron, Groupe Dziga Vertov, 1969). Even if he was a bit arrogant, Roger didn’t have the others’ egos. I met him as a student at the film school ran by Noël Burch and Jean-André Fieschi. He filmed one of his films in my building, in which I think Adolpho Arrietta was in charge of photography.

I also met Godard in 1995, when Marco Müller invited him to present Histoire(s) du cinéma in Locarno, on the occasion of the centenary of film. But Godard only accepted verbally and never fulfilled what he had promised: the book wasn’t edited and the exhibition never happened. He only took part in one of three round tables. Perhaps Godard’s attitude responded to the ides that the funds of the Swiss government were owed to him in any case, because he was of Swiss nationality. We saw each other in a few occasions then, because I was in charge of selecting the speakers for the round tables.

Going back to that ideological shake to montage and to the impact of the rediscovery of Russian avant-gardes in the critical evolution of Cahiers, what was left of American cinema after that? After that initial rejection of the New American Cinema, after that Soviet turn and the discovery of the new cinemas, did the view of classical cinema change in later film criticism?

On specific occasions, I can use the plural ‘we’ to refer to La Nouvelle Critique or Cahiers, but I can’t speak collectively here. The crux of the question is Nicholas Ray. In 1967 I left Unicité and abandoned active political life. I worked making subtitles, and that allowed me to see new films. And then Wim Wenders arrived, one of the most representative film-makers of the time, for whom I have great respect and with whom I have learned about music, although I wasn’t a fan of his films. During the period of politicisation we saw as the echo of a certain cinephilia that hadn’t reflected enough about what it was. Wenders was beginning to reflect, but in another way. As far as I am concerned, I couldn’t go any further politically. I had an in-depth knowledge of cinema, but I had to go back to all that I hadn’t understood before: American cinema, but in another way, trying to understand the films as a Frenchman, without focusing on the industrial context or the prestige of that particular film-maker at the time that the film was premiered. I knew the technique and the violent reaction of the Americans to or way of seeing his cinema. We were those who liked Jerry Lewis.

![[i]Lightning over water[/i] (Wim Wenders, 1980) img entrevistes eisenschitz05](/cinemacomparativecinema/images/ccc02/img_entrevistes_eisenschitz05.jpg)

During that time arrived Nick’s Movie, later called Lightning over water (Wim Wenders, 1980). My best friend, Pierre Cottrell was a key figure in the construction of the film, he knew well Wenders and his operator, Martin Schäfer, as well as the American crew and Pascale Dauman, who was still distributing his films and who was the first one to distribute, around 1972, American underground cinema. After organising a programme about the New American Cinema based on the work of five film-makers, she premiered La Région Centrale (Michael Snow, 1971). I didn’t see Chelsea Girls (Andy Warhol, 1966) in the famous screening at the Cinémathèque Française, but I did do in London, and even so, by comparison, Snow’s film was the film that had a bigger impact on me during that time, because it was so different to anything we were used to. Before those underground screenings organised by Dauman, we weren’t interested in that self-conscious American cinema. Those who wrote about it, such as Guy Fihman or Claudine Eyzikman, mostly looked for an institutional recognition. In Cahiers we were passionate about Sylvina Boissonnas, about the films of Philippe Garrel or Patrick Deval, the most interesting film-makers of the Grupo Zanzibar. Why were we excited by those films and not by the New American Cinema?

As far as the Cinémathèque is concerned, Langlois programmed three screening each evening, one in each room. He had screened for instance Louis Feuillade 6 one-hor film series in one day: the screening began at 18h.30 and finished at 00h.30, with a Little pause every two hours. We saw Fantomas (1913) or Vampires (Les Vampires, 1915), without intertitles, only following the images, something that was essential for Rivette. Among other long screenings, I would only highlight the 4-and-a-half-hour screening of Jaguar (1954-1967) by Jean Rouch, showing the unfinished film and commenting it. As Adriano Aprà said in his festival ‘Il cinema e il suo oltre’, Langlois, being a man of his time, had the capacity of inventing a cinema that went beyond cinema.

Let’s go back to Nicholas Ray. When Cottrell, who also worked making subtitles and to whom I frequently spoke, said that Wenders was preparing a film with Ray, I thought that it would be the perfect occasion of travelling to the US for the first time and observing. I visited the shooting for a week. Then, little by little, I kept a correspondence with his wife, who mentioned the possibility of writing a biography about him. She considered Nick as a hero, which is understandable in her case, but this wasn’t my attitude. The genre of the biography didn’t still exist in cinema, the only example I knew was Citizen Hearst (W. A. Swanberg, 1961), a reference for me, since it was based on documents; it was a beautiful book that taught me a lot about America. I started to have the desire to write a biography of Ray when I realised that it was a way to think about American cinema and the way we are used to writing about it. I asked myself if we would have treated it the same way had we known how it was made, since there they said that if that was the case we would have never taken Ray o Jerry Lewis seriously. Since Ray had ‘wounded’ many people that weren’t still dead and I didn’t want to upset them, I decided to approach the project not from a biographic point of view, but from the point of view of his working method as a film-maker. Biography played a part in the work of the film-makers that were no longer making impersonal films, as Howard Hawks, and were instead making films with a purely biographical sensibility: it is difficult to leave biography aside when writing about Ray’s cinema, for instance. By showing how the films were made, I aimed to prove that the Americans were wrong as well as to conciliate what my generation appreciated of American cinema (Ray represented an important possibility for us) and what it rejected (Ray was excluded from that system and concluded his career with a demented and experimental film, We Can’t Go Home Again [1976], which, as I see it, was linked to all his previous films, and forced us to review all his previous work as a form of commitment).

Anatole Dauman, the producer of Night and Fog (Nuit et brouillard, 1955) or Hiroshima mon amour (1959) by Alain Resnais, among others, prepared then a film with Elia Kazan about his relationship to Turkey, a project thus related to America America (Elia Kazan, 1963). I met Kazan in the Street, when I was with Glauber Rocha, who came often to Paris. In spite of the cinema he made, Kazan was someone warm and curious, so he was my first interviewee. Over the next five or six years, with the money I earned with the subtitles, I travelled to the US to continue conducting interviews during that transitional period in the history of cinema. When I started writing, in 1979, the first video recordings and VHS appeared, which offered the opportunity to watch the films again. But towards the end of the project there were many films that I wasn’t able to see again. On the other hand, the Major Studios thought that it was tax-wise more interesting to donate the official and personal archives to American university libraries. In Los Angeles, in the university library one can access the archives of the RKO, where Ray made at least half of his films. Labarthe also conducted his research on Orson Welles there. Studying the different versions of the scripts or the production archives, I could work according to the American criteria. Over time, I collected VHS and was able to watch the films again. This is why I titled the book Roman américain, rather than ‘Nicholas Ray’. For me, it was an opportunity to go back, in an objective way, to American cinema and the way we had seen it. For me, it was a personal journey, but one that was also satisfied my curiosity about non-film history, something rather rare amongst film writers: in Cahiers they saw me as the member that was most interested in history, something natural in Marxism. And American history is fascinating – not only the one about the crisis and the black lists, but also the rest. The book was, for me, like a shake and when I finished it I felt I have closed something. It wasn’t a very structured book from an academic point of view – there are certain documents I didn’t consult, I didn’t interview certain people; instead I let myself go due to the fatigue and the need to finish the book, which took me 10 years to write.

What was your experience of reviewing American cinema from another perspective at the same time that you received the impact of La Région Centrale?

There was a subversive side to Ray’s work that I may have intuitively sensed but didn’t see sharply when I began the book. It was the utopian side identified by Ray himself in Lightening over Water: he dreamt of another cinema that could concentrate everything in an image and could say everything via the image; with a stronger image than all the history of literature and music, in which one could find all of Dostoievski and Conrad. This is what he tried to do and what he did. It was such attempt that the film-makers of the previous generation had discovered in his work, such as Rivette, Godard or Truffaut: something that one recognises in They Live by Night (Nicholas Ray, 1948) or in Bitter Victory; these films show another form of making cinema, this is why his career was interrupted. My research reinforced the tradition of Cahiers. Ray moves forward by going beyond the rules set by Hollywood. It was like the anecdote of Fritz Lang and the “test tube babies”: Ray was presenting films in a university together with Fritz Lang and, after he began speaking, Lang interrupted him to say that what was going on in the world was horrible, that the next generation would only make “test tube babies”. He thought that even sexual pleasure would be extirpated from humanity. Ray replied: ‘But maybe that will be the ultimate kick: breaking the tube’. This was the idea: to follow the rules and at the same time try to break them. Rivette said that what was interesting about the book is that they couldn’t have imagined that Ray was a crazy visionary like Abel Gance.

And what was left of the French cinema then? I am thinking here of Eustache’s idea that French cinema had lost its intensity.

Eustache knew – I think he says it in a note to Jean-André Fieschi in Cahiers – that there are certain experiences that reach their limit, that when we reach a certain age, we understand that we won’t live the great impacts of the past again, be they a film by Pasolini or by Snow. For me, as for Eustache, who at the end of his life would only see the films he recorded from television, the experience of cinema changed at a certain point. He worked on several beautiful projects, not all of which have been published, but we couldn’t think of cinema as something to materialise. However he felt a great pleasure when watching certain films again and in finding in them the few things that really mattered to him. For me, it’s also complicated to assess what French cinema was then, because I never liked it that much. As a boutade, Daney said that it wasn’t French cinema that was good, but those who thought about cinema in France, the critics: Jean Epstein, Roger Leenhardt, Bazin… I can agree with him and at the same time, for a moment, believe in the absolute opposite. It’s obvious that this is false, as together with Hollywood cinema, Russian cinema – bar the aberrations of the dictatorship –, Italian cinema – in limited periods – and the Japanese one, French cinema is among the five most free cinemas of all history. In addition, it is the only one that achieved such freedom outside the studios and the great producers. That said, I like certain film-makers, not ‘French cinema’.

But the recuperation of a more radical cinema allowed ‘French cinema’ to see that other forms were possible, and in that sense I would like to speak about the importance of the figure of Glauber Rocha, which went beyond the forms of the young cinema that was being defended, and that were a Little codified, perhaps.

There were several cultural bubbles, and he brought them together. A European bubble, a Brazilian one, and a mass of instincts. With Rocha, at a certain point, I had to take a certain distance. He showed me Claro (1975), but I was never able to give him my opinion. I have no opinion about that film, I was no longer there. What was extraordinary about him is that, at the same time, he concentrated tropicalism, knew Eisenstein as well as we did, and was able to say what was it that separated him fundamentally from Pasolini.

What have been the decisive formal changes – comparable to your experience with Ray – in film-makers that, for you, could have renovated film itself?

I am not sure if we could find anything similar today. Perhaps it is in so-called ‘non-fiction’. Is it perhaps because the world changes? Because the cinema changes? Or, simply, because attention changes? I think that, from this point of view, Rouch was been more fundamental than Rosellini.

ABSTRACT

Conversation with the critic and historian Bernard Eisenschitz about the influence of 1920s avant-garde Soviet cinema in the magazine Cahiers du cinéma in the late 1960s and early 70s and specifically during the turbulent period in which he was part of the magazine (1967–72). Repercussion of the rediscovery of that cinema (in which Eisenschitz played a key role thanks to his travels to Moscow in the late 1960s) for the ideological line of the magazine: the impact, specifically, of Eisenstein and his writings, in an editorial team whose ideological father, André Bazin, was always against the manipulation through editing. The article also traces a parallel with the arrival of the ‘New Cinemas’ during that period. The political consequences of such rediscoveries are logically an important point in th period of critical radicalisation of which Eisenschitz narrates his own itinerary, which finally leads to a late revision of American cinema and Nicholas Ray.

KEYWORDS

Criticism, montage, Cahiers du cinéma, Sergei M. Eisenstein, André Bazin, Jean-Luc Godard, avant-garde, Soviet cinema, Dziga Vertov, Nicholas Ray.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AUMONT, Jacques (2012). Que reste-t-il du cinema ?. Paris: J.Vrin, Librairie Philosophique.

AUMONT, Jacques (1971). «S.M. Eisenstein : "Le mal voltairien"». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 226/227, January-February, pp. 46-56.

BELLOUR, Raymond (Ed.) (1980). Le cinéma américain. Paris: Flammarion.

BERTOLUCCI, Bernardo, EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (Trans.) (1967). «Le monde entier dans une chambre». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 194, October, 1967.

BRION, Patrick, DOMARCHI, Jean, DOUCHET, Jean, EISENSCHITZ, Bernard, RABOURDIN, Dominique (1962), «Entretien avec Billy Wilder». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 134, August, pp. 1-16.

COMOLLI, Jean-Louis, NARBONI, Jean (1969). «Cinéma/idéologie/critique». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 216-217, October-November.

DANEY, Serge, «Journal de l'an présent». Trafic, nº 3, August, 1992, pp. 5-25.

DELAHAYE, Michel, EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1967). «La Hollande entre (mise en) scène». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 193, September, pp. 7-9.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1968), «A ciascuno il suo». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 203, April, p. 66.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1968), «A dandy in aspic». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 203, April, p. 64-65.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (2001), «Affaire de travellings 1939. Frédéric Ermler et Alexandre Matcheret : deux films soviétiques». Cinéma, Autumn, pp. 63-81.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1969), «Bouge boucherie». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 212, May, p. 60.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1968), «En marche». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 205, October, pp. 52-55.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1968), «Ernst Lubitsch». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 200-201, April-May, p. 106.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (2011). Fritz Lang au travail. Paris: Cahiers du cinéma.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (Ed.) (2002). Gels et dégels : une autre histoire du cinéma soviétique, 1926-1968. Paris/Milan: Centre Georges Pompidou/Mazzotta.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1967). Humphrey Bogart. Paris: Le Terrain Vague.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1970), «I. "Ice" et les U.S.A.» Cahiers du cinéma, nº 225, November-December, pp. 14-15.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1969), «Jardim de guerra». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 213, Juin, pp. 8-9.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1966), «Joseph Losey sur ''Accident''». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 184, November, pp. 12-13.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1993), «Boris Barnet : journal de Moscou», Trafic, March.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1999). Le cinéma allemand. Paris, Nathan.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1970), «Le Proletkult, Eisenstein». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 220-221, May-Juin, pp. 38-45.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1968), «Les biches». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 200-201, April-May, p. 132.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (2000). Lignes d'ombre : une autre histoire du cinéma soviétique(1929-1968). Milan: Mazzotta.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1970), «Maïakovski, Vertov». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 220-221, May-Juin, pp. 26-29.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1969), «Porcile». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 217, November, p. 64.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1990). Roman américain. Les vies de Nicholas Ray. Paris: Christian Bourgois.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1970), «Sur trois livres». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 226-227, January-February, pp. 84-89.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1968), «The shooting». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 203, August, p. 65.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (1967), «Tourner avec Bertolucci». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 194, October, pp. 44-45.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard, GARCIA, Roger (1994). Frank Tashlin. Locarno/Crisnée: Editions du Festival international du film/ Yellow now.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard, KRAMER, Robert (2001). Points de départ. Entretien avec Robert Kramer. Aix en provence: Institut de l'Image.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard, NARBONI, Jean (1969), «Entretien avec Emile De Antonio». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 214, July-August, pp. 42-56.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard, NARBONI, Jean (1985). Ernst Lubitsch. Paris: Cahiers du cinéma.

EISENSTEIN, Serguei M. (1971). «Problèmes de la composition». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 226/227, January-February, p. 74.

EISENSTEIN, Serguei M. (1971). «Rejoindre et dépasser». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 226/227, January-February, pp. 90-94.

EISENSTEIN, Serguei M. (1971). «S.M. Eisenstein : de la Révolution à l'art, de l'art à la Révolution». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 226/227, January-February, p. 18.

EISENSTEIN, Serguei M. (1971). «S.M. Eisenstein : la vision en gros plan». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 226/227, January-February, pp. 14-15.

GODARD, Jean-Luc (1958). «Au-delà des étoiles». Cahiers du cinéma, nº 79, January, pp. 44-45.

LOURCELLES, Jacques (1999). Dictionnaire du cinéma. Paris: Robert Laffont.

PASSEK, Jean-Loup (1981). Le cinéma russe et soviétique. Paris: L'Equerre, Centre Georges Pompidou.

BERNARD EISENSCHITZ

Bernard Eisenschitz is a film historian and critic and translator of films and books. He is the author of Humphrey Bogart (1967), Ernst Lubitsch (1969), Douglas Fairbansks (1969), Les restaurations de la Cinémathèque française (1986), Roman américain. Les Vies de Nicholas Ray (1990), Man Hunt de Fritz Lang (1992), Frank Tashlin (1994), Chris Marker (1996), Le Ciéma allemand (1999), Gels et Dégels, Une autre histoire du cinéma soviétique, 1926-1968 (2000), Points de départ : entretien avec Robert Kramer (2001) and Fritz Lang au travail (2011). From 2001 until 2007 he directed the magazine Cinéma (thirteen issues), which published 10 DVDs with films that were then difficult to find. He collaborated extensively with the magazine Cahiers du cinéma, and took part in its editorial board. He has made several short Films and documentaries, such as Pick Up (1968), Printemps 58 (1974), Les Messages de Fritz Lang (2001) and Chaplin Today : Monsieur Verdoux (2003). As an actor, he has appeared in Out 1 (1971), by Jacques Rivette , La Maman et la putain (1973), by Jean Eustache, Les Enfants jouent à la Russie (1993) by Jean-Luc Godard, Le Prestige de la mort (2006) by Luc Moullet, L’Idiot (2008) by Pierre Léon or Les Favoris de la lune (1985) and Chantrapas (2010) by Otar Iosseliani. He has also worked in the restoration of L’Atalante (1934) by Jean Vigo.

FERNANDO GANZO

Fernando Ganzo studied Journalism at the Universidad del País Vasco, and is currently a doctoral candidate at the Department of Information and Social Sciences at the same university, where he has also taught at the Painting Department of the Fine Art School. He is Chief-Editor of So Film and co-editor of the journal Lumière and contributes to Trafic, he has taken part in research groups of other institutions, such as Cinema and Democracy and the Foundation Bakeaz. He also holds an MA in History and Aesthetics of Cinema from the Universidad de Valladolid. He has programmed avant-garde film programmes at the Filmoteca de Cantabria. He is currently undertaking research on Alain Resnais, Sam Peckinpah, and the isolation of characters via the mise en scene.

Nº 2 FORMS IN REVOLUTION

Editorial

Gonzalo de Lucas

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

The Power of Political, Militant, 'Leftist' Cinema. Interview with Jacques Rancière

Javier Bassas Vila

A conversation with Jackie Raynal

Pierre Léon (in collaboration with Fernando Ganzo)

Interview with Ken and Flo Jacobs. Part 1: Interruptions

David Phelps

ARTICLES

EXPRMNTL: an Expnded Festival. Programming and Polemics at EXPRMNTL 4, Knokke-le-Zoute, 1967

Xavier Garcia Bardon

The Wondrous 60s: an e-mail exchange between Miguel Marías and Peter von Bagh

Miguel Marías and Peter von Bagh

Paradoxes of the Nouvelle Vague

Marcos Uzal

REVIEWS

Glòria Salvadó Corretger: Spectres of Contemporary Portuguese Cinema: History and Ghost in the Images

Miguel Armas

Rithy Panh (in collaboration with Christophe Bataille): La eliminación

Alfonso Crespo