FILMMAKER-SPECTATOR, SPECTATOR-FILMMAKER: JOSÉ LUIS GUERIN'S THOUGHTS ON HIS EXPERIENCE AS A TEACHER

Carolina Sourdis

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Choosing the Fragments

The ideal class for me would consist on replacing my role as an orator to become a sort of disk jockey that would simply relate a series of film fragments. In fact, when I prepare a class, the first thing I always do is to think in front of the DVDs: Which ones should I put in the bag? It is like packing the luggage and choosing which books to take, you know they will determine and modify the journey. For me, the class is like that: the chosen materials would define the outline. It would be a brief itinerary through the excerpts. And I think the core is there, in creating an itinerary based on the fragments. If I do not do so, it is because I lack courage; it would seem I am not honestly gaining my salary. But I would rather simply be a guide, an instigator of those fragments. It would be ideal.

The access to cinema is gained directly confronting the films. Besides, we have this incredible tool that is the DVD, which makes possible to keep an image, slow it down, make relations between one frame and another; be able to see how a shot is illuminated, discover the film’s guts, its intimacy. When I was a young boy and I wanted to make films, I could not have imagined something like that. What book can replace this experience that let you watch the film with such intimacy? And nevertheless I feel it is not used well enough. Film lessons can be terribly speculative in a foreign way to the filmmaker’s thought. The direct confrontation with the movie is the best text for me. Like the first Protestants: What do we need the church for? We have the Bible. We don’t need any priests.

Certainly I always rediscover the fragments. For instance, some time ago I decided not to take to class films by Flaherty or Vertov anymore, because I thought everybody already knew them. But it is not like this. And I hate to take them for granted while talking about them. I show them again and again, and it turns out exciting each time. The merit is on the images and the implication while you watch them.

This is why I do not know how to begin without watching the images. They are the ones that restore the primary emotion, that fill you with admiration and awake the desire to talk about Flaherty again. Due to that reason I am not used to do it the other way around. I am always very stunned if the projector presents a breakdown and I have to start without having been able to project. Besides, the images always lead me to the idea, and never the opposite way around. Later, that idea will be the connection to other images. It is often the same while I’m making a movie: I discover what the class is about in the class itself.

Before, I honestly thought that my experience as a teacher had nothing to do with my experience as a filmmaker, because generally, I forbid myself to use my own examples in my workshops and my classes. But although I am using other’s excerpts, I realize that it is inseparable from my thought as a filmmaker, this is to say that the classes are modified accordingly to the things I discover or I start to question when I am preparing or thinking a new film. The workshops I gave while I was making Under Construction (En construcción, 2001) had Flaherty as the main axis. Whereas when I was making Guest (2008) I used more examples of direct cinema. I have started to discover this relationship that I formerly had not considered; I used to believe I left home the filmmaker when I gave a class.

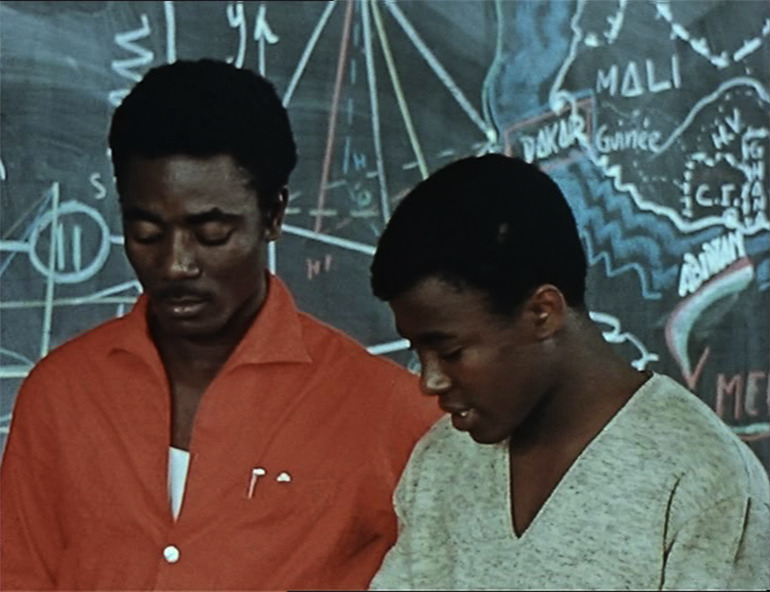

Below: Love Meetings (Comizi d’amore, Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1965)

The Transmission of Desire

Teaching, as almost everything, is a matter of implication. The school used to be very boring to me because the teachers were not implicated. It consisted, we all know, in learning by heart a list of Goths and Visigoths kings, the literature classes were about memorizing authors and works, even with qualitative adjectives: ‘Moratín is a naturalist and a colourist’. One time I asked what that of being a colourist should mean, and the teacher did not want to answer me. But against it, I remember a teacher that made an analysis of To a Dry Elm (A un olmo seco) by Machado, with such a beauty and an implication that it extraordinarily lead me towards a reading of Edgar Allan Poe. You can really feel it. And I have realized imposture is not valid in teaching, that desire is transmitted. This is the most important thing. In the first workshops I gave in Latin America, I first thought I should adapt the classes to their reality. I thought I might avoid experimental European films because they would feel them somehow foreign. It is a mistake. You should show the same. Everything is a matter of implication. Desire is transmitted, much easier and better than I thought.

On the contrary, it is very easy to astonish the students and gain their attention with some exclamatory scenes. There are teachers who do this in ignoble ways, who misuse the fragments looking for crashes, easy revelations, pleasing techniques, astonishing things. The academic analysis of Odessa steps, for instance, made the sequence become an absolute stereotype: it was always used to teach cinematographic montage. Not only all the students had seen it, but they had also examined it, without having watched, in fact, Battleship Potemkin (Bronenosets Potyomkin, Sergei M. Eisenstein, 1925). And what is worse, without having experienced what it feels to watch that sequence… It is the same that happens with the bath sequence in Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960): many people are not scared because they have rather studied it, dissect it and observe the horizontal lines against the verticals, the volumes. They have a completely sterile knowledge because they do not know what that series of procedures used by Eisenstein or Hitchcock, actually produce. They have not experienced it, and if they have not lived it, they are completely unaware about the reasons of its examination.

A film makes you feel different sensations, reflections and then, in a natural way you get interested in how it has been accomplished, in how the cinematographic forms have been worked to be able to arise those reactions. But in the academic analysis, any possibility of emotion is mummified: the forms are studied without comparing them to what they produce, or even without knowing it. This is why in praise for the fragment we get the risk of failing into the pathologies of the fragment, of converting it in a source of ignorance or manipulation, executed by the figure of the teacher-hustler.

Because of that, it is very important as well, to create the context of the fragment: what perspective do you choose, how do you place it? Sometimes you try to create the context of the film, some others of a decade, or of Soviet cinema in the twenties…and from there you are going to create a synecdoche of this decade and this revolutionary spirit that implied in such a way the cinematographic form, by choosing an emblematic moment that goes even beyond the film. It is our duty to create that background.

The Experience as Spectator

I find a paradox everywhere: people do not watch films, but they study them. Cinema is practically an unknown object of study. Even sometimes I question if the people that come to my workshops have actually seen my movies. And it is the exact opposite process that I lived when I was a boy. There were almost no films schools, not even books on cinema in Spain at the time. But there were a lot of cinema theatres and cineclubs in all the neighbourhoods. Everybody went to the movies, but nobody studied cinema, today everybody studies cinema, but no one goes to the movies. It is curious.

Many times when I give my courses, I get the proposal to make practices as well. In one hand, time is barely enough, because normally a workshop is between one and tow weeks long, and I think practices will result very banal in such a reduced amount of time. But above all, I perceive a flagrant scarcity: that of the student as spectator. And I see it in the movies as well. When I see a movie or a practice, the first impression I get is very often the same: They have not been good spectators. The most flagrant scarcity is the absence of spectators, at all levels, because nowadays in a certain way we can all make movies. What we are lacking are spectators, I would say.

In other hand, my cinema experience is inseparable of my experience as spectator. I do not know another one. I did not go to film school, therefore film theatres have been my only school and it is the only thing I know. In fact, to watch and to film are two completely reversible tasks, as to read and to write. It is unthinkable to imagine a writer that has not read. However, the technological access has encouraged a generation of people that film without having watched or read. For that reason I almost never consider the practices, because there is always a preliminary scarcity. I would like to think the practice, practicing first as spectator.

A key experience for learning is watching the film more than once, because usually when you just watch it once you only get some intuitions. But this is in a certain way very spontaneous: you have seen a movie over and over again, but not to learn a thing, just by pure desire, for the need of going back to it because you love it. In a very natural way you start to discover its structure, its forms… ‘This is said here so it is later related to this, this is the space that had not been shown from that other angle’… It should not be studied; you get to deduce it in a very natural and organic way.

Accompanying the Creative Process

The experience of my workshops in Cuba is beautiful because I am not supposed to give lectures there. I mentor the design and execution of the final film projects of the documentary course. Besides, it allows me to experience Cuba in a different way, as I work in seven projects each year and if possible, I go and see the settings where the students will shoot; places that would be impossible to access otherwise. The mentoring allows you to dream the movies as well, to appropriate them, keeping the respect towards the author so it becomes an autonomous work. But it allows you to think very different problems, exercise as a filmmaker, and think how issues that have not directly concern you in your own films can be solved. This is very interesting.

For these mentoring sessions I first ask them to send me a short synopsis. And so, I have established a pedagogical method: we are eight, and each day of the week we deeply address one of the projects. Sometimes they have barely a sheet or half a sheet written, but we try to deeply address it anyway. At the beginning of the session I ask the responsible of the project to go and sit apart from the rest. They cannot talk. They can only listen for an hour or two. I think I am Samuel Bronston, the film producer, with his crew, talking, speculating, and pointing out features of the film. Afterwards, the one that has been suffering in silence has the right to join us. This came out once randomly, and it gave such good results that I have schematised it.

Thus, in the workshops we start on paper and I only use the images for time to time, when I feel the need or if I can evoke a moment in a screen to visualize an idea that would be harder to nail down orally. We try to keep a conversation about the project. Finally to go deep into a single project reverts in that of others; everyone results changing their own project at the end of the day.

I truly like the model of San Antonio de los Baños. For instance, in the first year of documentary they have an experience called One to one. It consists on isolating the group of eight documentary makers in the farthest place in the mountain, a place that is reached by donkeys. There is a small camping of a regional television where they have the basic equipment. In this setting they have to choose a character to make a portrait –called One to One. They make it individually, but they collaborate with each other: they make their own portrait, and either collaborate with the sound or the image of others.

They go with a teacher, and the experience changes them all. Here, experience is prioritized over the technological knowledge, which unfortunately is what for many film schools comes first. Not even a technical knowledge, but a technological matter: The lens goes like this, or this other way, the axis, the jumping of the line… As if cinema could be read in a leaflet.

The Documentary Space

I find more interesting people, more promises, in the documentary field rather than in fiction. I filled in those Sight and Sound’s surveys, both in documentary and fiction, and I realized –although these are completely random lists, and I could make a different one from week to week and still feel absolutely represented– that in fiction my newest title was from 1973, The Mother and the Whore (La maman et la putain, Jean Eustache). Even out of twenty, I think I would neither have included a latter fiction. In contrast, in the documentary list there were, in fact, recent tittles. I feel it like a more fertile space of exploration, with such filmmakers as Wang Bing or Dvortsevoy.

I think documentary generates a sensibility that precedes learning, and the student feels that this space –as I always say documentary is rather a space than a genre– shelters them with a freedom and a new flexibility that fiction do not provide. They can speculate with time, with the points of view…

Restrictions in Creative Processes

However, I think we are wrong when we think that the student should have absolute freedom. The boundaries work quite well; you should learn how to be free within these limits. The kite flies because it is tied, if it is not, it will not. Creative thought is aroused through restrictions.

Many times the choice of the topic is a pernicious idea for the students. They always make their gamble on the topic, and I try to dismantle this idea. According to my theory, the importance lays on the perspective of the look and the choices they make regarding that matter; because in fact, the topic is something they should find through their look. That is why it would seem much more pedagogical to me to delimit the concept, even to interchange the student’s projects: ‘you are going to make this one, you are going to make that one’… Because then, regarding the choices that let them appropriate that material, a clearer cinematic thought is aroused. That is too, one of the best legacies of documentary. Often terribly dull commissions as might had been the one given to Alain Resains about the National Library of France, end up being appropriated in such a personal way that it was possible to create there, a space as intimate as the one created in Mareinbad Hotel.

This is why, facing conditions is precisely where an authorship can truly be liberated and visualized. Painters give us some lessons on that matter. Some time ago, I have been studying the clauses of the contracts that determined the commission that was made to the painter. The first one who made that inquiry was André Delvaux with his medium-length film Met Dieric Bouts (1975). Afterwards, in some art books I have punctually found some specific contracts. It would be a wonderful lesson regarding any painting, to be able to confront it to the contract that generated it in the first place. Unfortunately very few contracts are preserved, but it is really helpful to know the restraints when trying to discover the skills of the painter.

Cinema Trough Painting or Painting Through Cinema

I give a one-week workshop on painting. We talk about cinema without watching any film. For me it is wonderful, because sometimes a certain distance must be found to think cinema. There are a lot of contaminated ideas, spoiled images by the endogamy; by what is euphemistically called the world of cinema, so closed within itself. Painting is exactly the clarity of another distance from which you can discover with more excitement your own medium: cinema. This is precious to me, I have always thought about it. When I go to a museum, the criteria I have for the analysis and pleasure in relation to the paintings are the same of my experience with cinema, that which has structured my relationship with everything else. With literature and painting.

Translated from the Spanish by Carolina Sourdis

ABSTRACT

José Luis Guerin reflects on his teaching experience in relation to his filmmaker work. Firstly, in order to show the forms of a film, to transmit the desire, the emotion related to cinema and its processes of implication, he contextualizes the choice of the film fragments thus encouraging his students to the experience as spectators within the classroom. Furthermore, regarding the documentary workshops he imparts, and particularly based on the one held in The Escuela de Cine de San Antonio de los Baños (EICTV), he points out the benefits of establishing restrictions to stimulate and accompany the creative processes. Lastly, through his painting workshop, he reflects on the reversible look of painting and cinema.

KEYWORDS

Film excerpts, transmission of desire, spectator experience, creative processes, film workshop, documentary, look, painting through cinema.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

GODARD, Jean-Luc (1980). Introducción a una verdadera historia del cine. Tomo 1. Madrid. Alphaville.

LANGLOIS, Henri (1986). Trois cent ans de cinéma. París. Cahiers du cinéma/ Cinémathèque Française/ Fondation Européene des Métiers de l’Image et du son.

MEKAS, Jonas (1972). Diario de cine. Madrid. Fundamentos.

VVAA. José Luis Guerin, Images documentaires, n°73/74, junio de 2012, París.

CAROLINA SOURDIS

B.A in filmmaking by Colombian National University, M.A. in Film Studies and currently a PhD researcher in the Department of Communication at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona. She is member of the Latin-American Observatory of Film History and Theory. She won the Colombian Culture Ministry National Scholarship on film and audiovisual investigation in 2010. Her investigations have primarily approached montage and film archives in Colombian documentary, as well as filmessay in European Cinema.

Nº 5 PEDAGOGIES OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Editorial. Pedagogies of the Creative Process

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTOS

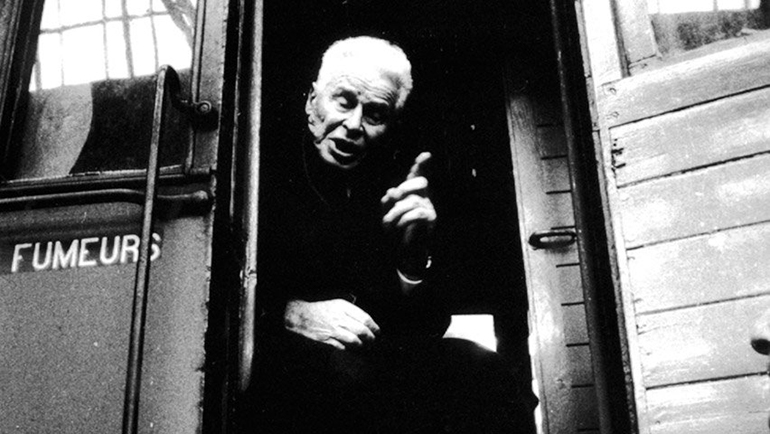

The Goodwill for a Meeting: That's cinema

Excerpts by Henri Langlois, Jean-Louis Commolli, Nicholas Ray

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Filmmaker-spectator, Spectator-filmmaker: José Luis Guerin's Thoughts on his Experience as a Teacher

Alain Bergala

Filmmaker-spectator, Spectator-filmmaker: José Luis Guerin's Thoughts on his Experience as a Teacher

Carolina Sourdis

ARTICLES

In Praise of Love. Cinema en Curs

Núria Aidelman, Laia Colell

A Daring Hypothesis

Jonás Trueba

To Shoot through Emotion, to Show Thought processes. The Montage of Film Fragments in the Creative Process

Gonzalo de Lucas

The Transmission of the Secret. Mikhail Romm in the VGIK

Carlos Muguiro

The Biopolitical Militancy of Joaquín Jordá

Carles Guerra

REVIEWS

AA,VV. BENAVENTE, Fran y SALVADÓ, Glòria (ed.), Poéticas del gesto en el cine europeo contemporáneo.

Marga Carnicé Mur