IN PRAISE OF LOVE. CINEMA EN CURS

Núria Aidelman, Laia Colell

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHORS

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Introduction

Cinema en curs1 is defined as a film pedagogy program in primary and secondary schools2. The program is conceived from the desire and the need to encourage children and young people to discover, in a profound and active way, cinema as an art and as a creative process. A kind of cinema which they wouldn’t have any access to or to which they might never know anything about (as many adults also don’t know) if it is not introduced in school. An unknown cinema, which many believe to be far away from their interests but which can precisely be the nearest to them.

Cinema en curs is carried out with groups of students between ages 3 and 18, during the school’s hours, all year round and with the participation of teachers and filmmakers. Although entering the education system causes some friction and intricacies, it creates important opportunities: to be able to work and create the project together with the teachers, to give cinema a central role in the school and to develop the extraordinary pedagogic potential of cinema. In Cinema en curs cinema is transmitted through a methodology that generates a way of seeing and of making films that forms, that transforms; that is able to make us grow and to make us better (not only students, but to everybody in the process).

Film as Creation

One of the fundamental principles of Cinema en curs is the conception of cinema as creation, as a poetic process in the etymologic sense of the word. José Angel Valente, in one of his first essays, Conocimiento y comunicación [Knowledge and communication] (1956), with a brief and beautiful statement disagrees with the period’s thoughts which comprehended poetry and communication: ‘A change of perspective that would radically understand poetry as something nearer the nature of the creation process, could reveal that poetry is, essentially, a way of comprehending reality’ (VALENTE, 2008: 39). In Cinema en curs, cinema is understood as poetics and, such as poiesis, as a way of knowledge, of thought, emotion, amazement, interrogation of ourselves, the others and the world. This principle structures all the processes and methodologies. Thus, it specially is a base for the workshops, where there is a tight relationship between the viewings and the creative experience, between watching and making films.

In his essential essay L’Hypothèse cinéma [The Hypothesis of Film] Alain Bergala explains his idea on the ‘pedagogics of creation’: ‘The idea is to push our logic and imagination to an earlier time in the creation process, to the moment in which the filmmaker has to choose between different options’ (BERGALA, 2007: 128).

The purpose, thus, is to see cinema through the eyes of the filmmaker, to feel ourselves as the creator by being conscious of his gestures and his choices, to share his emotions. It is the same reconstruction of the process that Paul Valéry stated in his Introduction à la méthode de Leonardo de Vinci [Introduction to the Method of Leonardo Da Vinci] (1894); the same look that Vladimir Nabokov required to his students in the lecture on european literature; the same that Jean Renoir expects from spectators:

‘The qualities, gifts and education that make a painter are the same as the gifts, education and qualities that make an art lover. In other words, to love a painting, you must be a potential painter. There is no other way to love. And, truthfully, to love a film, you must be a potential filmmaker […]. Even if it only is through imagination, one must make films; if not, he doesn’t deserve going to the movies’ (RENOIR, 1979: 27).

They all share the idea that real comprehension and authentic pleasure need participation. Stefan Zweig develops this idea in The Secret of Artistic Creation (1938):

‘[…] I don’t believe in a purely passive pleasure. I also don’t think that anybody who enters a museum for the first time, or who listens one of Beethoven’s symphonies for the first time, could easily appreciate the masterpiece. A piece of art should not be impacted directly on anyone […]. To be able to feel it, we should feel again what the artist has felt. […] We should feel his soul in ours, because a real pleasure is not only sensed by receiving it, it comes from working in collaboration. […] Therefore, we learn and assist the artistic process while living the act of creation through all of its phases’ (ZWEIG, 2004: 217-219).

It is not casual that this small but significative list of authors that have been defending for decades an approximation to art as a creative process for spectators or readers, is formed, precisely, by creators.

To discover and comprehend art, and cinema in our case, is not related with the simple acquisition of technical terms, which usually is the starting point (and ending point) of most ‘lessons on cinema’. An example of this kind of teaching, and probably the greatest exponent, is the description of the different shot scales; another could be the different ways to edit or the analysis of the structure of a script. ‘Equipped’ with these terms, students ‘analyze’ film sequences and ‘identify’ these notions while they ‘interpret their meaning’. In this logic, if the ‘correct’ words have identified the correct aspects of the sequence, the student shows his knowledge on the matter. ¿But what has he actually seen? ¿What has been learned? To identify something means to reduce it to an established term, to close it in a limited meaning, to impose what we already know over what we have seen.

Therefore, in Cinema en curs we avoid the idea of ‘literacy’. Amongst everyone who is literate, who is actually able to enjoy the words of a poem or the sentences of a character’s description? Or, furthermore, does an alphabet for film, for paintings or poetry even exist?

We are, precisely, searching for the kind of knowledge related to our senses and our pleasure; that knowledge which reminds us of the origin of the word saepere, which is also associated with flavor, with taste.

In Zweig’s text, the words and expressions that appear together with pleasure and joy are those related to work, difficulty, to the impossibility of comprehending from a passive state. Love and the ability of enjoyment are also learned. And for this learning process, to have the opportunity to pass through the creative experience is certainly an exceptional path. Experiencing the creative process –that is, to a conduct creative practice in a reflexive manner– allows students to place themselves in the creators side in a much intense way; it allows them to experience doubts, difficulties and the emotions that come with creation.

The Screenings: Watching Creation from Nearby

Watching film excerpts is a central activity in the discovery of cinema that we develop in Cinema en curs. These are fragments that last between 2 and 10 minutes and that are arranged in different categories3.

Without a doubt, watching excerpts cannot substitute the absolutely irreplaceable experience of watching a whole film at the cinema. Therefore, we also undertake many activities in which we go watch films at the theatre, we assist film festivals, etc. But, to comprehend film, working with excerpts has a great potential. It allows students to learn about different filmmakers from completely different periods and styles such as Jean Vigo, Johan van der Keuken, Chantal Akerman, José Luis Guerin, Ermanno Olmi, Robert Bresson, Yasujiro Ozu, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Roberto Rossellini, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, Isaki Lacuesta… It allows students to become interested or feel addressed by different filmmakers and, specially, it allows them, without the need of any imposed lecture or a historic itinerary, to understand the many ways of thinking and making cinema. The students can comprehend, thus, that any truthful filmmaker offers different ways of creation and of approaching the world; that the universe of film offers thousands of adventures where, each and every one of us, with our own sensibility and individual taste, can find their own place.

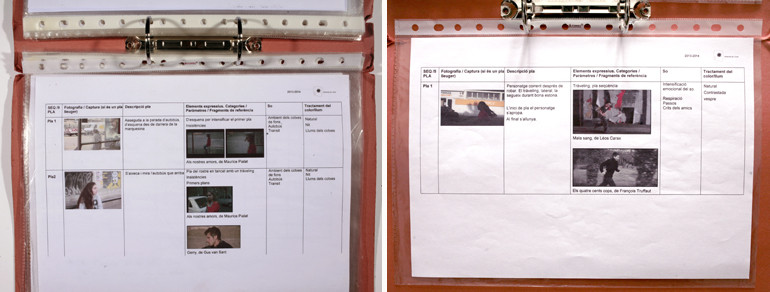

Excerpts grant a broadness and openness that doesn’t endanger a deep view on the subject. To view excerpts implies to re-view4. At Cinema en curs screenings imply a sense of ritual: we always start with a first projection, with the lights off and in complete silence; later, the students have a time to individually take notes or to think on their first impressions of what they have seen; then, different screenings of the same fragment take place, stopping in shots, going back, remembering, discussing, watching (and listening!) again. Discussing a 3 minute excerpt can take from 20 or 30 minutes until almost an hour. This will depend in what the fragment generates in the students and their interest in the discussing. Finally, in their film notebooks, the students take notes on what they have thought is more relevant of the shared discussion, writing down, always, the name of the filmmaker and the title of the film.

The main focus of the screenings is to discuss about what we see and what we hear; our main objective is not knowledge but attention: to be able to observe and recognize the filmmaker’s decisions and gestures in both image and sound. Therefore, questions and observations are very important during the process: How does the filmmaker film his character in an emotionally intense moment? What happens in the interval between the camera and the character? Are the sound and the image linked together? Have we taken a look at the light? And at the color palette? What are the editing decisions?

One of the filmmaker’s main functions at the workshop is to ask questions. It also becomes one of the functions of the teachers who, year after year, have learned the gestures of cinema and come to be the best allies in the students’ discovery of film.

To ask and to call attention, thus, to make attention possible: sensibility and the capacity of perception are sharpened, value is given to things that could initially seem unimportant, the filmmakers decisions are emphasized and relations are created between the excerpts. Discovery happens during the same process of looking and describing. What is learned through fragments doesn’t come from some external knowledge nor need any other validation. It is an evident knowledge.

Another of the filmmaker’s main functions during the screenings is to share his passion, his wonder while watching a film, the love and admiration, the emotion, he feels towards films and their creators.

The Practice: Creating in Partnership with the Screenings

We make films with the same attention, openness, gentleness and requirements as we watch films. During the creative process, students situate themselves in the same dialogue space as the filmmakers, feeling very touched when they discover that they share with them the same gestures5, from their first experiences until their final documentary or fiction short film which marks the end of the workshops.

The first experiences introduce two aspects: the direct dialogue with cinema and the filmmakers, and the discovery of their surroundings through film. The initiation value of these experiences, thus, is the ability of transforming the students’ gaze.

During the first nine editions of Cinema en curs, the workshops started with Lumière Minutes. After looking carefully and with enjoyment different Lumière films, the students explore their town or neighborhood through the demanding look of the Lumière Minutes: one-minute documentary shot conceived as the first filmmakers and that intend to have the same intensity. Goats coming out of a farm, a panoramic view of Montserrat’s cable car, workers disinfecting themselves at the meat factory, workers from the recycling factory dismantling televisions, dolphins dancing, the land mower coming towards the camera… This search encourages students –and, with them, also teachers and filmmakers– to investigate their near surroundings, to visit unknown places of their environment (a factory, a farm, a garage…) or places that, reviewed through cinema, obtain a new value.

In the tenth edition, we’ve introduced an experience that had been already tested during the processes of creating films. We’ve call it ‘Shots of the world’ and it proposes students to film their surroundings in three ways: ‘Space diaries’, ‘Travellings’ and ‘Portraits’. The dialogue with the filmmakers is an intimate conversation. Many students start filming from their windows, following David Perlov’s first shots of his Diary (1973-83): ‘I want to approach the everyday. It takes time to learn how to do it’. Others, impressed by the night shots of News from home (Chantal Akerman, 1977), have explored their neighborhood by night. Dana expresses it with a clear and intense voice over her shot (‘Nine o’clock at night. I film from my balcony inspired by Chantal Akerman’). Some, after filming from a car a night scene, remember the excerpt they saw of Les mains négatives (1978), by Marguerite Duras. And, as in Daguérrotypes (1975) by Agnès Varda, others have portrayed their grandfathers or other people of their daily life presenting themselves to the camera.

Therefore, students discover cinema accompanied by the mentioned filmmakers and many others. It is, thus, a very strong discovery: to be able to frame the world, the vertigo when facing infinite choices, the wonder and the trust in film and in the world when we truly look at it. At the same time, the intensity of experiencing creation influences the way in which they approach new films and excerpts, they are able to do it with the emotion of perceiving the beat of a shot.

The dialogue with filmmakers and their films also continues, in other ways and through other paths, during the process of creating a short film, which finalizes the workshops. The whole process is complex, it has many steps –from documentation, writing the script and editing the film–, and, since we wish to develop it with a cinematographic accuracy and with a pedagogic value, it makes us questions ourselves many things. How to get children and young people, without any previous vocation to cinema, start thinking about cinema from cinema itself? How should we develop the process so that students become the real subjects of the creation, so that cinema could be for them a medium to understand the world?

Parting from the students’ reflection and analyzing the experience of the team, integrated by teachers and filmmakers, we have developed during these years different methodologies that answer these and other questions. In this article, we will explain the ones related to the screenings6.

In both the fiction and the documentary workshops we work with DVDs that include film excerpts divided in categories. As an example, lets quote some of the sections of the DVDs for the fiction workshop. The section dedicated to The Face Value is structured in the following categories: ‘Showing emotion while hiding the face’, ‘Shooting from behind to intensify the close-up’, ‘Close-ups’, ‘Persistences’. The section Passages between the character and the world contains: ‘Passage through movement’, ‘Passage by cut’, ‘Relay shots’, ‘Digressions’ or ‘The world between sequences’. Although it is not a formal or technical approach, these categories allow us to approach cinema from deep cinematographic matters. Emotion is another fundamental aspect while selecting and organizing the excerpts: the change of distances between the character and the camera during a traveling that accompanies him or the city traffic between the camera and the character, are emotion bearers. Just as it is also very moving to watch a take that stays for a while on a face or to enjoy the cut of a shot. We are not talking about the emotion of the story; it is the emotion of the shot itself, between the shots, of cinema.

Students, thus, search in their films a way to express emotions cinematographically. And this search is possible thanks to the viewings and the questions that have arisen: they provoke the students’ desire to make a huge and complex panoramic shot from some trees to the main character who is crossing a path; it provokes students to decide to shot a sequence on a train so that in a downhearted moment of the character his face remains hidden by the darkness of the tunnel and overwhelmed by the sound; that the opening scene of a documentary is formed by traveling shots of their neighborhood and a voice over in the first person, and that portraits of people posing in front of the camera creates the closing scene.

This way of relating to film doesn’t have anything to do with the imitation nor with the application of ready-made prescriptions. It comes from dealing with profound cinematographic matters, from exploring (through the screenings and the creative experience) the expressive capacity of the cinematographic gestures.

Other times, the relationship with the screenings passes through desire: Gus Van Sant’s circular traveling in Gerry (2002) has awaken many times the desire of experimenting that gesture; Jean-Luc Godard’s, Claire Denis’ and Bela Tarr’s night sequences have inspired many shots and sequences of illuminated buildings at night and of characters running through streets accompanied by the rhythm of the streetlights; Depardon’s long traveling that starts Profils payasans: La vie moderne (Raymond Depardon, 2008) has also inspired more than a group to start their documentary with a frontal traveling; Antoine Doinel’s escape and look to camera at the end of Les quatre cents coups (François Truffaut, 1959) is repeated in Rocío’s character who, trapped also as Antoine, runs towards the sea and ends up interrogating the spectator with her gaze.

Trust in Cinema and in the World

On the occasion of the Cinémathèque’s retrospective of Louis Lumière in 1966, Godard, while thanking Langlois for discovering the true story of cinema, said that what really interested Lumière was the extraordinary of the ordinary, and that if Lumière didn’t talk about the future it was because, at the beginning, cinema was an art of the present but, after all, it was the medium that approached art to life (GODARD, 1966: 281). This is the kind of cinema for which and with whom we work in Cinema en curs.

The children and young people that have entered the path of viewing and making cinema while having a profound dialogue with filmmakers, have discovered –because of their experience– that the initially awkward cinema has actually many things to tell them, to concern them, to communicate with them. This same kind of cinema allows them to talk, to express their experiences and concerns, to show their life and their places, to know themselves and get others to know them, to know their daily environment and to make it known to others.

During the workshops, cinema has entered their lives, it has made them grow. And cinema itself has also grown a little bit with them. In just some months, a deep and trustful relationship is created with cinema. On one hand, a trustful relationship is forged with the value of the duration of a shot, the emotion of a movement or with a change or rhythm or light. On the other hand, trust in the medium of cinema as a tool to show that a face can be infinite, that the neighborhood that seemed trivial actually hides marvelous changes of light; that the solitude we sometimes feel but we cannot understand can actually be shared; that a movie about the frequently distressing emotion of growing up can even move those adults who appeared to be so faraway. These cinema strengths are not inherent, the filmmaker has to earn them: from Lumière, Renoir, Cassavetes or Mekas to the thousands of children and young people that have participated in Cinema en curs in these ten years. But, how do we earn them? Through expectations, by being demanding (with ourselves, with others and with cinema), and, most of all, through trust: trusting cinema, trusting the world, others and ourselves.

Transformed by the experience of cinema, we no longer need a camera to be a filmmaker. To be a filmmaker is, above all, a way to be, a way of being in the world.

Translated from the Spanish by Alejandra Rosenberg.

ENDNOTES

1 / Cinema en curs proposes a triple game of the Catalan/Spanish term en 'curs/en curso': it means in progress, a course and a school year.

2 / Cinema en curs started in Catalonia in 2005, and is also currently being implemented in Galicia, Madrid, Argentina and Chile.

3 / Please see Gonzalo de Lucas’ article in this same issue.

4 / In his lecture on european literature, Vladimir Nabokov said that ‘one cannot read a book: one can only reread it. A good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a rereader. [...] The element of time does not really enter in a first contact with a painting. In reading a book, we must have time to acquaint ourselves with it. We have no physical organ (as we have the eye in regard to a painting) that takes in the whole picture and then can enjoy its details’ (NABOKOV, 1997: 26).

5 / Serge Daney praises it in relation to filmmakers: ‘La beauté du cinéma, c’est que c’est un art où Garrel fait les mêmes gestes que Griffith, il y a une sorte de mémoire anthropologique des gestes, celui d’Eisenstein déroulant à la main un morceau de pellicule pour regarder...’ (DANEY, 1994: 163-164).

6 / More about the creation process of Cinema en curs can be read in Jonás Trueba’s article in this same issue and in Cine en curso. La transmisión del cine como creación y la creación como experiencia (AIDELMAN and COLELL, 2012). All the films can be seen in the website: www.cinemaencurs.org/en

ABSTRACT

The article exposes some of the methodologies of Cine en curso, a film pedagogy program developed in schools and high schools with students between ages 3 and 18. The first part of the article argues two of the program’s main principles: 1) the importance that the discovery of cinema lies in a creative approach, and, therefore, as a means and mode of knowledge, thought, emotion; 2) the commitment for a film transmission that awakens the joy and love for cinema. The second part of the article describes some of the processes and approaches that Cine en curso practices to stimulate the students in this approximation and appreciation towards film: 1) the approach to cinema from the place of the filmmaker, considering the different issues of creation and enjoying the cinematographic emotions; 2) the importance of “learning to see”; 3) discovering cinema through film excerpts of important filmmakers, organizing this discovery through different cinematographic concerns; 4) the close relation between the viewing and the practice. The text concludes by highlighting the value of cinema as a way of being in the world.

KEYWORDS

Cinema en curs, pedagogy, transmission, methodology, learning to see, screenings and creative experience, creative process, film excerpts, school, Alain Bergala.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AIDELMAN, Núria y COLELL, Laia (2012). Cine en curso. La transmisión del cine como creación y la creación como experiencia (pp. 231-242). Revista TOMA UNO, 1. Córdoba (Argentina).

BERGALA, Alain (2007). La hipótesis del cine. Pequeño tratado sobre la transmisión del cine en la escuela y fuera de ella. Barcelona. Laertes.

DANEY, Serge (1994). Perséverance. Entretien avec Serge Toubiana. Paris. P.O.L.

GODARD, Jean-Luc (1966). Grace à Henri Langlois. BERGALA, Alain (ed.), Jean-Luc Godard par Jean- Luc Godard. Paris: Éditions de l’Étoile-Cahiers du cinéma (1985).

NABOKOV, Vladimir (1997). Curso de literatura europea. Barcelona. Ediciones B.

RENOIR, Jean (1979). Entretiens et propos. NARBONI, Jean (ed.) Paris. Cahiers du Cinéma.

VALENTE, José Ángel (2008). Conocimiento y comunicación (pp. 39-46) Obras completas II. Barcelona. Galaxia Gutenberg.

VALÉRY, Paul (2010). Introduction à la méthode de Léonard de Vinci. Paris. Gallimard.

ZWEIG, Stefan (2004). El misterio de la creación artística. (pp. 199-220) Tiempo y mundo. Barcelona. Editorial Juventud.

NÚRIA AIDELMAN

Lecturer in Audiovisual Communication at Pompeu Fabra University and a member of the CINEMA group. Together with Gonzalo de Lucas, she edited Jean-Luc Godard: Pensar entre imágenes (Intermedio, 2010) and she has written articles for a range of books and anthologies. These include Plossu Cinéma, Jean-Luc Godard: Documents and Erice-Kiarostami: Correspondances. She was a programmer for Xcèntric and Gandules (Centre of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona) between 2003 and 2011.

LAIA COLELL

Graduated in Humanities at Pompeu Fabra University. She received her Advanced Studies Diploma (DEA) after carrying out scholarship-funded research into the Cahiers of Simone Weil in Paris. She is currently working on her doctoral thesis. She has translated various books on philosophy and cinema and is a member of the Research Group ‘Bibliotheca Mystica et Philosophica Alois M. Haas’ at the University Institute of Culture of Pompeu Fabra University.

NÚRIA AIDELMAN AND LAIA COLELL

They are joint directors of A Bao A Qu, a non-profit cultural organization devoted to the conception and development of programmes and activities that link artistic creativity with schools. Cinema en curs (which started in 2005) is the foundation project of the organization, while other notable projects include Creadors en residència als instituts de Barcelona (Creators in Residencie in Barcelona High Schools, 2009), Fotografia en curs (2012) and Moving Cinema (2014).

Nº 5 PEDAGOGIES OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Editorial. Pedagogies of the Creative Process

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTOS

The Goodwill for a Meeting: That's cinema

Excerpts by Henri Langlois, Jean-Louis Commolli, Nicholas Ray

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Filmmaker-spectator, Spectator-filmmaker: José Luis Guerin's Thoughts on his Experience as a Teacher

Alain Bergala

Filmmaker-spectator, Spectator-filmmaker: José Luis Guerin's Thoughts on his Experience as a Teacher

Carolina Sourdis

ARTICLES

In Praise of Love. Cinema en Curs

Núria Aidelman, Laia Colell

A Daring Hypothesis

Jonás Trueba

To Shoot through Emotion, to Show Thought processes. The Montage of Film Fragments in the Creative Process

Gonzalo de Lucas

The Transmission of the Secret. Mikhail Romm in the VGIK

Carlos Muguiro

The Biopolitical Militancy of Joaquín Jordá

Carles Guerra

REVIEWS

AA,VV. BENAVENTE, Fran y SALVADÓ, Glòria (ed.), Poéticas del gesto en el cine europeo contemporáneo.

Marga Carnicé Mur