A DARING HYPOTHESIS

Jonás Trueba

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

To have a vocation ourselves,

to know it, to love it and serve it passionately;

because love of life begets a love of life.

Natalia Ginzburg, The Little Virtues

As time moves on, I’m becoming more aware of the responsibility one gains from life experience. I grew up in a family of filmmakers –our love for cinema was transmitted in a natural way. Only later did I become aware of how privileged I was, which is probably, in fact, my biggest inspiration when assuming the task of transmitting my experience in any educational context. I never dared to define myself as a teacher –I have too much respect for that profession. But I’ve increasingly realized how much we, filmmakers, are able to transmit and enrich the experience of teaching. It is not easy to find a word that is able to explain the idea of transmission between people. In France, people use the ‘passeur’ figure. Some French dictionaries speak of rowers that cross rivers in small boats to explain the original meaning of the word; others use it to talk of people who help others cross borders illegally, which is maybe not that far away from the meaning we’re looking for.

When Núria Aidelman and Laia Colell translated La hipótesis del cine [L’hypothèse cinéma] by Alain Bergala, they used the word ‘passer’ [‘pasador’] to describe it, which is probably the best solution to refer an equation that is known to many filmmakers who are interested in film transmission, either inside or outside the educational context. I remember the impact Bergala’s treaty had on me from the day I read it, not only when facing a class of film students, but also in my daily life, my development as a filmmaker, and my way of understanding film as such. L’hypothèse cinéma was about taking sides and find that other place that helps us build a distinctive initiation path, one that is more personal and assumes the art of cinema as something to be transmitted and experimented instead of being taught.

These translators turned into the best ‘passers’. With this French legacy, they created Cinema en curs –first in Catalonia, then in several other places before coming to Madrid just over a year ago. I was then lucky enough to be invited to take part in this project and collaborate, as a filmmaker, in a school in Orcasitas, a Southern peripheral neighbourhood of the capital, something that turned out to be one of the most enriching experiences in my life.

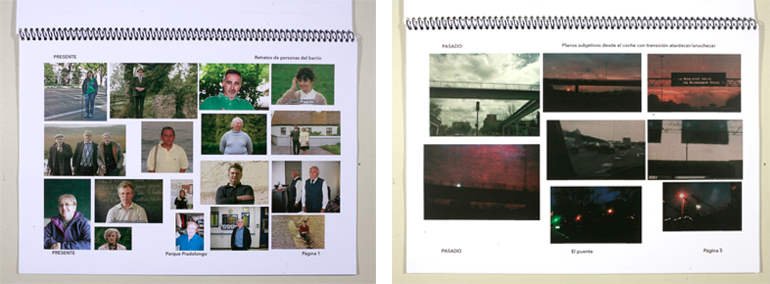

This workshop developed throughout twenty sessions with students aged 15-16 in the last year of Compulsory Secondary Education [4th grade of ESO – Educación Secundaria Obligatoria], where teachers, educators and myself learned how to assimilate different methodologies that have been developing and expanding for the past eight years in different primary and secondary schools. The workshop was part of the Documentary modality in the Cinema en curs annual program, with the goal of making a short-film that would allow a better contact with the reality of a neighbourhood with a particularly rich historical and social context. One of the main ideas of the project is to encourage a stronger interest from students in their everyday environment through the fresh eyes of cinema. The documentary form certainly deepens this kind of approach.

The young students first documented different spaces and typical characters in the neighbourhood of Orcasitas with texts and photographs, thus renewing their connection with something that seemed too near or familiar to attract their attention. I realized that the filmmaker should face this first moment as a spectator caught in these initial images and other information compiled by his students, for they are the ones who are responsible to transmit everything that is impossible for a newcomer to know first hand.

The students thus become the workshop’s main figures, which creates an initial transmission that comes from their work and their confidence in us. It is important to stress the privilege for many filmmakers in the Cinema en curs program of contacting certain places and people that we wouldn’t normally get to. In my case, I only knew Orcasitas through ordinary information that gives an extremely reductive image of it, usually focused in conflicts and problems caused by years of poverty and lack of basic resources. The workshop students, mostly composed of Orcasitas residents and, in some cases, sons and grandsons of their original inhabitants, didn’t want to repeat this vision. They were clear enough in their efforts to show a different image of their neighbourhood –one that is truer and especially brighter.

I believe that their will to capture the beauty and many surprising shades of their daily environment came to them naturally after seeing excerpts of films shown to them in our first sessions, thus accompanying our first practical explorations: Portraits (1987, Alain Cavalier), Innisfree (1990, José Luis Guerin), Shoah (1995, Claude Lanzmann), Profils paysans, le quotidien (2005, Raymond Depardon), Amsterdam Global Village (1995, Johan Van der Keuken), Public Housing (1997, Frederick Wiseman), or News From Home (1977, Chantal Akerman), just to cite a few of the most inspiring pieces to the students. These fragments were previously arranged and catalogued in DVD‘s and respectively shared with every fiction and documentary workshop –titles that aren’t usually available to a wider audience. I remember talking to a filmmaker colleague about films that I was watching in class with these students, and he’d look back at me as if I was crazy. But I would then answer back with simple facts: these young people weren’t showing any kind of rejection or distance towards the kind of films they were discovering in our workshop. On the contrary, their lack of prejudice allowed them to watch these fragments with a clean perspective and without any preconceived idea.

These fragments were analyzed and discussed in class by the students, allowing them to be more perceptive and develop an insight that is more sensitive and too often concealed. It is all about becoming more familiar with the way different filmmakers have been successfully telling stories through images and sounds in order to emulate and adapt them to our own circumstances. We know there’s nothing new about this, even Picasso started off by imitating his masters. But the important thing is to assimilate some initial references to begin with and later question ourselves under their perspective. With these excerpts and projections, we learned how to value the precision of a frame, the poetry of a camera movement, or even hundreds of ways to describe a light atmosphere, but also the research and hard work that lies behind every sensation that comes from it. Besides the old socratic method of obtaining reflexion and reasoning through questioning, we also had decisions and choices made by consensus between students in dialogue with teachers and the filmmaker. A shooting-script was then built to film and later edit into a short-film –one that was eventually called Diary of a Neighbourhood [Diario de un barrio, 20141].

Filmmaking in a school necessarily implies learning teamwork and many rich details that are hard to quantify. Technique and the global use of image and sound equipment are also important, like editing programs and devices, but we try to be concise and meticulous in their use to leave room for the students’ instinct and intelligence, thus giving the material side of cinema no more than its essential space.

I remember the shooting and editing days as being particularly happy for everyone involved. Those were the moments where students felt as definite filmmakers: by materializing their own previous choices, taking decisions in the spur of the moment, or reacting to accidents and unforeseen situations through intuition. One would see a particular student’s enthusiasm, like Laura’s, while she’d hold a boom pole to create a sound panoramic from a faraway freeway to the voices of children playing in a park. The previous afternoon ended with a splendid magic hour that fascinated the eyes of several students, touched by a magic light that seemed to caress the buildings in their neighborhood’s horizon. Every one of them knew how lucky they were to grab these precious moments on film. Another moment came through David and Yara, who decided to rise early in order to film the sunrise over the lake at Pradolongo Park. An unexpected fog covered the sunrise but gave them the possibility to grab a few shots of rare beauty. I also remember the revelation that other students had during the final edit when finally facing the material they had generated themselves, assuming their errors and finding infinite possibilities in film writing. The result is a lovely film that makes them feel proud and responsible, to which they look at with self-criticism but, at the same time, knowing how to recognize the huge amount of work behind it, for they’re the ones who must first learn how to value it when seeing the film in different projections and contexts.

This first year experience was essential to understand the reach and potential of the Cinema en curs program, but I was already witnessing its true essence and happily revolutionary side just a few months before. Then, just before school year started, the filmmakers involved in the workshops participated in its annual training in Catalonia, which I attended for the first time. We met in a huge house in Cantonigròs for a couple of days with the Cinema en curs team, including some thirty teachers from several educational establishments. Most teachers already had accumulated years of experience and commitment to the project –some of them since its first year–, others were also present for the first time, just before they’d start their first workshop. A teacher had recently retired but did not want to miss the formation and assumed all coordination and transmission tasks with newcomers.

We all shared our thoughts, debated and reflected together in order to build the new annual program, while commentating previously chosen film excerpts, worked on shooting and editing practices, but also gathered round to analyze different experiences and suggest new ways of working. It was a true laboratory of ideas where everyone participated. This exchange between teachers and filmmakers turned out to be fundamental.

It was particularly moving to hear more experienced teachers discover how much they had assimilated the philosophy of Cinema en curs and made it their own by applying it, year after year, to the circumstances of their own classes, thus earning an idea of film that is difficult to attain by the majority of industry professionals. These teachers had understood, in a complete, organic, and experimental way, that cinema is not something to be orchestrated in the development of curricular activities, but an art that serves people and is able to maximize our better side. This is what seemed to be truly revolutionary: that cinema may find a place in schools like it never had managed to, taking an active part in the life of students and teachers to nurture their sensibility, their look, their capacity to listen, think and reflect, or even the way they relate to each other and organize themselves.

Those teachers understood the transversal force of this project while overcoming any sort of fear or temptation to resist. We know that it is not easy to penetrate the educational system and pretend to transform the ideas that were instituted in it, or mandate what education should be like in schools. But what I also know is that this is a revolution I want to belong to.

Translated from the Spanish by Francisco Valente

ENDNOTES

1 / Film directed by ESO 4º class (15-16 year-old students) of Colegio Montserrat-Orcasitas (Madrid): Raúl Álvarez, Christian Aranda, Alba Benítez, Yara Castellanos, Cristina Cercas, Javier David del Valle, Noelia Fayos, Héctor Gregorio, Jorge Gualda, Andrea Huertas, Laura de Leonardo, Alejandro Maurín, David Morán, Marcelo Pinto, Raúl Plaza, Sergio Portalo, Teresa Quintana, Manuel Rodríguez, Daniel Solera, Rocío Vargas, Marina Villa, Iván Viñuelas. Mentored by Jonás Trueba (filmmaker) and Virginia González, José María Maestre, Arturo Marín, Jesús Muñoz, Montserrat del Olmo, Javier Rodríguez, Mª José Rodríguez, Margarita Romero (teachers).

ABSTRACT

The author begins the article by reflecting on his involvement in film transmission based on his experience and commitment as a filmmaker. He then narrates about his experiences in his first Cine en curso documentary workshop and exposes the workshop’s development in all its phases. He highlights a few fundamental elements in each one of them, particular several discoveries throughout the creation process: documentation, by means of texts and photographs; screenings of excerpts and how to awaken sensibility, appreciation, and capture beauty; a script built by means of consensus; teamwork and the magical and revealing moments of shooting the film; editing and the infinite possibilities of film writing. Cinema becomes part of life and the experience is highly transforming for students and everyone involved in the project. In the article’s final part, the author emphasizes in the importance of teamwork between filmmakers and teachers, and the value of the teachers in the project, highlighting their profound understanding of film and their decisive role in the transforming and revolutionary entrance of cinema in schools that Cine en curso brings to play.

KEYWORDS

Cinema en curs, transmission, experience, creative process, screenings, documentary, teacher training, school, workshop, Alain Bergala.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BERGALA, Alain (2007). La hipótesis del cine. Pequeño tratado sobre la transmisión del cine en la escuela y fuera de ella. Barcelona. Laertes.

GINZBURG, Natalia (2002). Las pequeñas virtudes. Barcelona. El Acantilado.

JONÁS TRUEBA

He wrote and directed the feature-length films Every Song is About Me (Todas las canciones hablan de mí, 2010) and The Wishful Thinkers (Los ilusos, 2013) along with the medium-length film Miniaturas (2011). He was co-screenwriter for the films Más pena que gloria (2000) and Vete de mí (2005), directed by Victor García León, as well as El baile de la victoria (2009), directed by Fernando Trueba. He is the author of the book Las ilusiones (Periférica, 2013) and he writes about the cinema for the newspaper El Mundo on the blog El viento sopla donde quiere. He combines his cinema work with his role as lecturer at TAI College of Arts and Entertainment (Madrid). In 2013 he joined the Cinema en curs team.

Nº 5 PEDAGOGIES OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Editorial. Pedagogies of the Creative Process

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTOS

The Goodwill for a Meeting: That's cinema

Excerpts by Henri Langlois, Jean-Louis Commolli, Nicholas Ray

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Filmmaker-spectator, Spectator-filmmaker: José Luis Guerin's Thoughts on his Experience as a Teacher

Alain Bergala

Filmmaker-spectator, Spectator-filmmaker: José Luis Guerin's Thoughts on his Experience as a Teacher

Carolina Sourdis

ARTICLES

In Praise of Love. Cinema en Curs

Núria Aidelman, Laia Colell

A Daring Hypothesis

Jonás Trueba

To Shoot through Emotion, to Show Thought processes. The Montage of Film Fragments in the Creative Process

Gonzalo de Lucas

The Transmission of the Secret. Mikhail Romm in the VGIK

Carlos Muguiro

The Biopolitical Militancy of Joaquín Jordá

Carles Guerra

REVIEWS

AA,VV. BENAVENTE, Fran y SALVADÓ, Glòria (ed.), Poéticas del gesto en el cine europeo contemporáneo.

Marga Carnicé Mur