SUSANA DE SOUSA DIAS AND THE GHOSTS OF THE PORTUGUESE DICTATORSHIP

Mariana Souto

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

The António Salazar dictatorship, which ended more than four decades ago with the Carnation Revolution, still leaves traces today in both Portuguese art and society. Contemporary Portuguese cinema often addresses this historical period from different aesthetic perspectives – fiction films such as Cavalo Dinheiro (Pedro Costa, 2014) or Tabu (Miguel Gomes, 2012) and documentaries such as Linha Vermelha (José Filipe Costa, 2012) approach the issue in a variety of forms, subtle and direct, and regard subjects as diverse as the colonial wars, African immigration, the revolutionary process and the land occupation. Amongst the directors who deal with the “Estado Novo” nowadays, Susana de Sousa Dias is one of the exponents – the dictatorship is the centerpiece of her movies 48 (2009) and Natureza Morta (2005).

Below: Cenas da luta de classes em Portugal (Robert Kramer and Philip Spinelli, 1977)

The gaze on these films is characterized by a historical distance, radically different from the cinema made shortly after the fall of the regime. Torre Bela (Thomas Harlan, 1975), As armas e o povo (Union of cinema workers, 1975), Cenas da luta de classes em Portugal (Robert Kramer and Philip Spinelli, 1977), and O bom povo português (Rui Simões, 1981), for instance, were made at the heat of the moment and are endowed with a sense of excitement and urgency. Demonstrations, public speeches, the crowd movement, celebrating parades on the streets, and interviews with large groups of people are present in most of these films. Some of them use unstable images or found footage from amateur filmmakers. With a powerful sense of spontaneity, they witness a singular and special moment in Portuguese history. Leaving the censorship behind, they try to think about the Estado Novo and rewrite the events of those years.

Susana de Sousa Dias departs from this aesthetic and creates a specific way of reflecting on this same period. Her movies have a certain sobriety, a mourning reflection, even an introversion –which can be related to her belonging to another period in history, years away from the Salazar era and his fall, as well as a social context of individualization and micro–historical perspectives. While the films from the 70’s are forged in macro-historical and sociological tendencies, dedicated to the representation of groups (the Portuguese people, the soldiers, the marines) with little individuality, and the interpretation of the revolutionary process as a matter of class struggle (the fascism as an imposition of the dominant class and the revolution as a subversion of the working class), Sousa Dias’ focuses, mainly in 48, on subjectivity through the stories and the memories of individualized former prisoners.

Her first feature-length film, Natureza Morta, is made with the use of pictures (from the PIDE-DGS archive –“Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado/Direção Geral de Segurança”, the political police of the regime)– and moving images (of Salazar, official ceremonies, popular demonstrations, all from a variety of sources like news reports, propaganda films, television records, etc). She changes the speed of the images, slowing them down to a point when they seem more like photographs coming to life than slow motion movies. And if we think of them as “moving photographs”, it looks as if they are oddly provided with volume and depth. In addition to that, the director uses very long fades –the cinematography resembles candle lighting, and people merge with the darkness, giving them a similar look to an apparition, or ghost–.

The sound of Natureza Morta is also slowed down. The soundtrack is composed of dissonant and unfamiliar noises; some of them resemble the sounds of slamming doors, or old and squeaky hinges and chains. Therefore, the soundtrack is somehow disconnected from the images; working within the imaginary of the haunted house and the horror movies, its goal seems to be setting an atmosphere of danger, torture and fear. Even though the movie is categorized as a documentary, it has a great deal of abstraction and experimentalism as well as elements of the scary movies in the fiction field. Thus, from this perspective, perhaps we could say Natureza Morta is a “horror documentary”. In this sense, it is possible to track an affiliation with O bom povo português, which also uses very decelerated images, strange noises and transmits an idea of weirdness and haunting. These effects in Rui Simões’ film, made in 1981, also seem to put into perspective the images of the Carnation Revolution, but in his case he tends to the irony. Edited a few years later than the others films previously mentioned and past the moment of euphoria, O bom povo português sees the Revolution with a dose of frustration for its deployments. At last, the power did not go to the people, contrary to some socialist expectations.

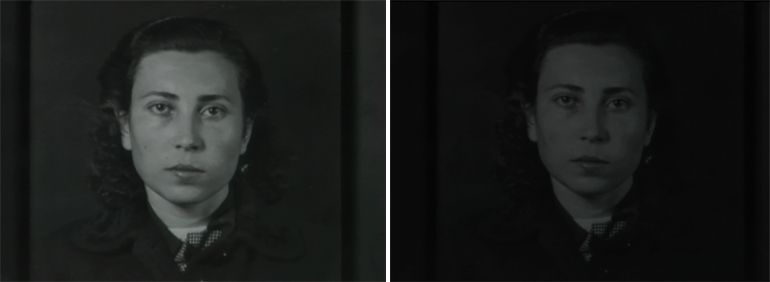

As Simões, Susana de Sousa Dias, uses material produced by the Estado Novo itself, but subverts its primary intentions. With the manipulation of the images and sounds of the Power, she produces a discourse that reflects upon it and resists from the inside, turning the found footage of the government into her own weapons – with similarities and differences when compared to the gestures of Harun Farocki and Andrei Ujica in some of their films with found footage. The idea of working with the portraits of the political prisoners, present in parts of Natureza Morta, becomes central in her next movie, 48 (2009). Her third and most well known film had a positive reception in festivals around the world and won the Grand Prix of the Cinéma du Réel in 2010. This documentary is entirely made from identification portraits of the PIDE and the vocal testimonies of these same people, interviewed years later by the filmmaker. While we watch the static, black and white, images of the photographs, we hear their voices from the present. They are survivors of the dictatorship, living in freedom some decades after the Carnation Revolution. The title “48” stands for the duration of the Estado Novo –from 1926 to 1974, the longest dictatorship in Western Europe in the XX century–.

48 is built around an extremely simple and minimalist dispositive. However, at the same time, it is very rigorous, since it’s confined by its own rules for almost the whole length of the movie, with little variation. Behind the apparent simplicity of the dispositive, there is an exhaustive body of research as well as a meticulous conception of editing and sound design. The editing dedicates a long exposure time for each photograph and also to the silences in between the speech of the characters. These pauses are important and stop the images from being overpowered by the text, so that there isn’t a relation of subordination of the images by the sound. Each portrait appears and disappears in a sufficiently slow rhythm, so that the spectators can observe and investigate those faces and expressions with full attention, comparing or making associations with the words they hear. Sometimes the time even lasts long enough for the faces to become abstract forms, or outlines, contrasting points of light and shadow.

After all, time and duration are important to the film – one of the most violent aspects of the Portuguese dictatorship is precisely its duration, 48 long years. Some of the people interviewed by Sousa Dias grew old in prison. In other cases, we can see, among pictures from different times, an untimely and forced aging, due to the adverse conditions of the imprisonment. In other words, the film captures not only the aging that happens naturally in prison, but also the aging that happens because of it. The slow fusion between the pictures of a young face and an old one of the same person shows the endurance of the years in jail. Time deforms people.

Besides the silences already mentioned, the soundtrack of 48 is composed of little noises that come from the interview context at the present (a clock, some car at the distance, a person touching some object, movements of the clothes, etc). The testimonies are not registered in the studio, with a clean audio, but rather in an environment that evokes some closeness, maybe a home. The noises, then, contribute to the construction of a cinematic space –the spectator can sense the situation of co-presence between the interviewer and the interviewee that took place somewhere in the world–.

If, during the regime, the silence was both an imposition and a strategy (‘the silence is the cry of the dead and the word par excellence of the political prisoner: condemned to silence, it is also by the silence that he resists to torture’1) (LEANDRO, 2012:35), at the present time, the word recovers its strength. The speech is not used for the interrogatory, against the will of the militant, but for the testimony, in his or her favor.

Some of the people interviewed in 48 mention that the possibility of resistance in prison was silence or their own facial expression. ‘We cannot escape from taking the picture, but we can choose the expression we put on’, says one of them. The face is the place of the enigma, screen to the marks of the time, sometimes the place of a contradiction (like the case of a young woman who takes a smiling picture to the police and feels guilty about it). In their essay on Faciality, Deleuze and Guattari (1996) say that the head, even the human head, is not necessarily a face. The face is produced by humanity, it happens when there is a social production. We could think Susana de Sousa Dias proceeds to something similar: she conducts an operation which transforms a number of heads into faces, giving them voices, subjectivity, dignity, identity, past, present, and history.

Of course other filmmakers in cinema history have experimented with the power of the faces watched very closely (Dreyer, Cassavetes, Bergman, to name a few), but not so many took this idea to the extent of making the whole film focused on it. As 48, Screen tests (Andy Warhol, 1964-66) and Shirin (Abbas Kiarostami, 2008) are examples of films that are exclusively made of human faces in all their duration, although moved by very different purposes.

In Sousa Dias’s work, we see faces in pictures – sometimes two or three portraits of the same person in different periods of time. Here and there, the faces stand for an idea of the identity and the theme of the recognition intersects the movie in several points. With the photographs in their presence, the former prisoners are stimulated to talk about this materiality: the way they looked at that time, the visible traces captured by the camera. One of them notices the wrinkles and remembers the greenish color of his skin as the result of the sleep deprivation. Another one talks about his weight gain because he couldn’t move in prison. Others about the ugly expression they made to confront the police. A son of a character didn’t recognize the parent since they were separated so early in his life and he only had one old picture as a reference. In some cases, the characters don’t recognize themselves in the images. Thus, recognition is an important theme to 48, along with the way the dictatorship acts upon it: modifies, ages, mutilates, and deforms people. The torture, the fear and the long time imprisoned had very concrete and visible effects on these people’s faces, bodies and identities.

Besides the faces, 48 leads us to think about the complex history of the looks that crossed those images (LINS et al., 2011). A variety of looks and temporalities dwell on the pictures: the people in the portraits look us directly in the eyes. First of all, the eyes of the prisoners meet the eyes of the police and then, years later, meet the eyes of the spectator. The look escapes the police device of the past and penetrates the present. They survive to make contact with us more than 30 years later. The recovered footage evokes the moment of its production, the unique instant of shared presence of the bodies and the camera. Some aspects of the relation of the police and the prisoners are impressed on the pictures and become visible to us. As Jean-Louis Comolli says, the cinematographic document is, first of all, the document of its own realization:

‘In order to understand the coordinates of a shot or a photograph, it is important to considerate not only its space-temporal and political-historical conditions, but also what happens between those who film and those who are filmed. I would say that if something is documented, it is that relation’ (COMOLLI, 2010: 339).

The photographs, by the way, are not just placed into the editing, they are not frozen frames, but rather filmed, which provides them with a breathing, almost imperceptible motion. In other words, they are not static, but cinematographic. As in Natureza Morta, they are slowed down, sometimes to 1% of the original speed. In both documentaries, the spectator feels the slowness of the passage of time, which, once again, is connected to the long duration of the Salazar dictatorship. In addition to that, the fusions, fades and voices separated from the images give her films a fearful atmosphere. Although the movie is made with the survivors of the regime, there’s still something phantasmagoric about it. Maybe the detachment of body and mind (the overlap of a mute body in the pictures from one time and the disembodied voice from another period) produces ghosts, splits the souls as isolated beings wandering around with no materiality.

If before the movie the PIDE photos were part of a catalogue, almost a taxonomy, now they can be seen as elements of an audiovisual album, an album filled with affection, but also with horror. In other words, Susana de Sousa Dias’ films work to implement a change in meaning and purpose of these documents: from being instruments of registration, identification and control of the political prisoners, they transform into important pieces in the creation of subjectivity and preservation of memory. The editing of 48 and Natureza Morta works against the intentions of those who first produced these archives. And this displacement is probably the biggest political gesture of the film: turning the production of a control apparatus not only into live testimonies of the violence, but also into an aesthetic expression of horror.

FOOTNOTES

1 / In the original: ‘O silêncio é o grito dos mortos e a palavra por excelência do prisioneiro político: condenado ao silêncio, é também pelo silêncio que ele resiste à tortura.’

ABSTRACT

This article seeks to investigate Susana de Sousa Dias’ work as one of the exponents of the Portuguese cinema made about the Salazar dictatorship. 48 (2009) and Natureza Morta (2005) utilize portraits of political prisoners and found footage from the police in order to criticize and reflect upon the regime and its consequences on people’s lives. Thus, the director produces a discourse that resists from the inside, turning government material into her own weapons. Describing Sousa Dias’ work in editing and sound design (for instance the change of speed of the images, the lighting, the slow fades, the soundtrack composed of dissonant noises), the paper argues that these films set a phantasmagoric atmosphere and seem to be part of what we call “horror documentary”.

KEYWORDS

Documentary, Portuguese cinema, Salazar dictatorship, found footage, photography, 48.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

DIDI-HUBERMAN, Georges (2003). Images malgré tout. Paris. Les Edition de Minuit.

LEANDRO, Anita. A voz inaudível dos arquivos. A: SOUZA, Gustavo; CÁNEPA, Laura; BRAGANÇA, Maurício; CARREIRO, Rodrigo. XIII Estudos de Cinema e Audiovisual Socine. Vol. I. São Paulo: Socine, 2012. p. 27-37.

LINDEPERG, Sylvie; COMOLLI, Jean-Louis. Imagens de arquivos: imbricamento de olhares. Entrevista com Sylvie Lindeperg. A: Catálogo do forumdoc. bh. 2010. Belo Horizonte, Filmes de Quintal/FAFICH-UFMG.

LINS, Consuelo; REZENDE, Luiz Augusto; FRANÇA, Andrea (2011). A noção de documento e a apropriação de imagens de arquivo no documentário ensaístico contemporâneo. Revista Galáxia, 21, 54-67.

MARIANA SOUTO

Mariana Souto is a PhD student at the Communication Department at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Brazil, where she is finishing a thesis on the social class relations on Brazilian contemporary cinema. She was a visiting researcher at Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona (2014-2015). She works with art direction and costume design.

Nº 6 THE POETRY OF THE EARTH. PORTUGUESE CINEMA: RITE OF SPRING

Editorial. The poetry of the earth

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

The soul cannot think without a picture

João Bénard da Costa, Manoel de Oliveira

A certain tendency in Portuguese cinema

Alberto Seixas Santos

To Manoel de Oliveira

Luis Miguel Cintra

The direct experience. Between Northern cinema and Japan

Paulo Rocha

Conversation with Pedro Costa. The encounter with António Reis

Anabela Moutinho, Maria da Graça Lobo

ARTICLES

The theatre in Manoel de Oliveira's cinema

Luis Miguel Cintra

An eternal modernity

Alfonso Crespo

Scenes from the class struggle in Portugal

Jaime Pena

Aesthetic Tendencies in Contemporary Portuguese Cinema

Horacio Muñoz Fernández, Iván Villarmea Álvarez

Susana de Sousa Dias and the ghosts of the Portuguese dictatorship

Mariana Souto

REVIEWS

MARTÍNEZ MUÑOZ, Pau. Mateo Santos. Cine y anarquismo. República, guerra y exilio mexicano

Alejandro Montiel