THE THEATRE IN MANOEL DE OLIVEIRA'S CINEMA

Luis Miguel Cintra

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

I have been many times confronted with the affirmation that Manoel de Oliveira’s films are very theatrical and I have questioned myself about the reason of this undeniable presence of theatre in his films. These are uncomfortable matters to me. I do not want to deny you the right to meddle in my trade, but I, who have lived in theatre for so long, don’t recognize theatre in his films. What I see in his films is not theatre, not even what it would be called filmed theatre. I only see cinema.

But there is at least one certain thing. Since 1963 Manoel de Oliviera has used theatrical texts for eight of his films: Acto da Primavera (1963), Past and Present (O Passado e o Presente, 1972), Benilde or the Virgin Mother (Benilde ou a Virgem Mãe, 1975), The Satin Slipper (Le Soulier de Satin, 1985), Mon Cas (1986), A Caixa (1994), Anxiety (Inquietude, 1998), The Fifth Empire (O Quinto Império, ontem como hoje, 2004). And he has introduced theatre in many other films: Francisca (1981), where characters attend to the theatre, Lisboa Cultural (1983), where there is a theatrical representation inside the Hieronymites Monastery, The Divine Comedy (A Divina Comédia, 1991), where several crazy characters represent scenes, I'm Going Home (Je rentre à la maison, 2001), where the main character is an actor. And there are some scenes of Le Roi se Meurt by Ionesco, and Porto of My Childhood (Porto da Minha Infância, 2001), where the filmmaker himself plays the actor Estêvão Amarante in a theatrical scene. The theatre is really one of the central topics of his films and a dominant presence in certain phase of his work, the 70’s and 80’s.

For me, everything begins with Acto da Primavera, that film which I consider truly poetic art and which marks his clear entrance to the production of fictions. It was the first of his films I saw, overwhelmed. I still can remember my emotion: I did not want to believe in the miracle. I had not known anyone who had looked into theatre from cinema as well. He made theatre like I understood it: the representation of life. I became then forever faithful to his cinema, and this is the film I have forever considered to be the founding act of his work, even though it arrived already in the sequence of other great works.

Acto da Primavera begins with the first words of the Gospel According to St. John in off, spoken by a peasant: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made. In him was life; and the life was the light of men. And the light shined in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not.’ The topic of the film and, finally, of the whole work of the filmmaker emerges from here: life as a mystery, how men do not understand the miracle. And as soon as we hear this, we see images that would be guessed from a documentary and that by their juxtaposition are a representation of humanity after the sin, after Adam: the peace of original nature in the shepherd with the sheep, the labour in the digger’s hoe, war and violence in the bull combat, the game with the sticks, and the strange gathering of the messy multitude and the military helmets (to repress it?); the course of time with the old woman of long white hair who combs at the pace of the young, and evidently, the relationship man/woman in the scene between the young woman that will play the Samaritan and her lover burning in desire. Yes, the woman, her vanity and her lie. And even the wedding: she was not with her husband. And little by little, social life is penetrated: people who meet in the streets of the town, the square where the news are read, the progress (with the news of the arrival of men to the moon), until the announcement of theatre is heard. ‘Come and see! Come and see!’ The announcement of the play brings the preparation for the performance: the construction of the decors, the distribution of the costumes, the actors going to the place, the arrival of the villagers that will attend, the bourgeois audience like presumptuous and dulled tourists… Until the machine of cinema itself (or its representation) appears on the screen: In front of the actor that will open the show, Manoel de Oliviera himself is operating the camera and giving orders to the sound engineer to record the voices and sounds. Finally, in the top of the pyramid, the screen coincides with what Oliviera’s camera is recording: the shot of the actor himself, in a long angle that ennobles him. He addresses the audience aware of the responsibility of the moment, in such a solemn and artificial tone that he almost sings. And the actor begins defending, for ever, almost as a celebrant, the reason of being of this structure of production of sense: ‘Contemplate this sinners!’. Watch the video HERE.

For me, the whole definition of Oliviera’s cinema can be found in this sequence. Passing from documentary to the actor, and with him, to the construction of the artifice as the best way of capturing the truth of a mysterious reality: human life. In the film introduction, with the biblical text overlapped to the most constructed sequence of non-staged images, we find the definition of the cinematic matter: men both as creation of God and sinners. The image of men in society and of his relationship with others is represented progressively as the images start to focus in the life of the village. Art is inserted when that man starts to represent himself as a man linked to the religious vision which gives him sense in front of other men, in front of ‘any sinner’. Theatre arrives. And Oliviera places himself, in fact, in front of the theatre, or even better, in front of this idea of theatre, filming it, this means, filming the man representing himself in front of others through the Passion of Christ; others, who instead of being an audience become just people.

It is in the light of this symbolic sequence, of this incredibly beautiful and simple declaration of principles defined for the first time in the opening sequence of this film (and I would not be surprised if Oliviera’s way of being in the world had lead him to expose it, in such a clear way, when he starts to get away from documentary and begin to stage what he films), that I get to see the nature of the presence of ‘theatre’ in Oliviera’s films. And I believe henceforth, even when he films novels or history, he will never stop filming life through the construction of an evident and strange ‘theatre’ which might sometimes use theatre texts properly speaking, the stage and a performance of the actors that could be defined as ‘recited’, but which is, above all, an evident construction of a ‘mask’, or of a process of ‘denaturalization’ of the filmic matter towards a distancing effect with the spectator. This effect, above all, leads the spectator to become responsible. It makes him think, see and hear life differently, transformed or ‘represented’ by itself. It makes us see beyond what we normally see, and feel the (impossible?) need to give sense to it.

In the opening of Acto da Primavera, structured in the relation of cinema with its audience, this is, with the existence of other people, it becomes clear how fundamental this relationship is. For Oliviera, to make a film is to present himself to the world, to take part in life, in a certain way to celebrate it like the peasants in Curalha do in the representation. And to do it without traps, with the game rules laid bare. A theatre, like an idea, is the exposition of that same conviction: a stall (people alive) in front of a conventional space for the construction of artifices (the stage or the scenography) where other people alive (the actors) expose themselves with costumes (the parts) to represent the life that does not stop being present in their own bodies and souls. It is comprehensible that Manoel de Oliviera turns to theatre and its attributes as a process of his cinema or his artistic thought. Several times he uses it again as clear as in Acto. In the introduction of The Satin Slipper, more than ever, with the entrance of the audience to the San Carlos Theatre, Moliere’s blows and the screen inside the stage itself; In Anxiety, in the transition of the first to the second ‘story’ with the mise-en-abyme of Os Imortais through the closing of the curtain over the representation, and the actors who were finally on stage (but who were not in the shooting, in fact, as it becomes evident with the scene of the picnic filmed at open-air) bowing the characters of the next ‘story’; In the separating parts of Mon Cas with the theatre curtain, the comedy and tragedy masks, and ‘claquette’. But what interests him is not theatre. Theatre is a tool for his own way of ‘representing’ that even as a ‘representation’, in this case cinema, is always the fixation, in images, of the life he has filmed.

Deep inside, it is an artifice produced by an author-artist which wants to be shown as such, which bravely lets itself be seen in order to stop cinema to become that machine of illusion, of evasion of our intellectual responsibility as spectators, that oblivion of ourselves that so wonderfully cinema can become. It is more of an instrument to work the life that cinema can be, like the light, photography, the camera movements or montage, and that, as deep inside all arts, is simultaneously an instrument for a better understanding on the least evident truth of life.

And what does this artifice fundamentally consist on? Why we recognize in that strangeness of Oliviera’s cinema something called ‘theatre’?

I believe there are three points: the space, the text, the actors and maybe time. We all notice how the position of the camera is felt in this cinema. Almost the whole filmed action is organized according to the camera, without internal alibies of fiction. Just like in the theatre. As if the frame, later the screen, was a proscenium. The epitome of this is the shooting of Mon cas, where, on the other hand, the process of Acto is repeated: in the final moment of joy, when Job is cured by God from his leprosy and is given great descendants in the ideal city, the situation is inverted and the stall where the camera and the whole crew is, is seen from the stage. The camera looks itself in the mirror and shows the process. The camera seems to want to be noticed. And the space, more than Job’s ideal city, is the distance from the camera to the actor. And in the film theatre, the audience will be where we now see the filming machine. I will never forget the day when Oliveira told me for the first time, in my function as his actor, the contrary of what any filmmaker would have said: ‘Look at the camera’. And another day (because he never gives closed lessons) he added: ‘Remember that when you look at the camera you are looking to the film theatre.’ We can say: ‘Nothing is more theatrical.’ Yes, because there is a direct game with the audience and because no one forgets in stage that the spectators are in front, in the stall, looking at us, and there is no fourth wall in the stall that makes someone forget that the actors are in stage, in a conventional place of ‘representation’. But is this how theatre is made? Representing to the front? Very few times. In theatre the artifice is the opposite: we mainly look at each other in order to pretend the public is not there. But the characters are ‘put together’ in the stage according to the eyes of the spectators as well, like here. The figures are distributed in the space according to what the camera sees, and almost never for internal reasons of the fiction, which besides confuses many actors that learned as a rule that in cinema the camera does not exist: it is the keyhole. It is different in this cinema. The actor is, as it is obvious and for good, representing in front of the camera, as in theatre in front of the audience. How many times Oliviera fakes the look of actors in a face-to-face situation, with profile shots, according to what the camera sees (in order for the eyes of the actors not to remain white, without pupils) to the point of deframing their natural relation, so the fiction of their dialogue becomes completely artificial? And the theatre-sensation comes from here, from this vision of the camera. Because if usually the sensation of the space is similar to the one created in theatre with the audience, this is not the relation that is reproduced here but rather its reinvention with the filmic media. The distance between the spectator and the actor varies with the size of the shot, the camera moves during each shot or from shot to shot, it enters the space of fiction. The relations stage/stall are endless, there are as many as shots in the film, and that does not happen in theatre. And when, at the end of Benilde, the camera reverses to show that Regio’s house, where the film originally takes place, was finally a decor inside a studio, we say it is theatre, but there is no stage where those decors could have been constructed nor one where the figures could haven been deployed as such.

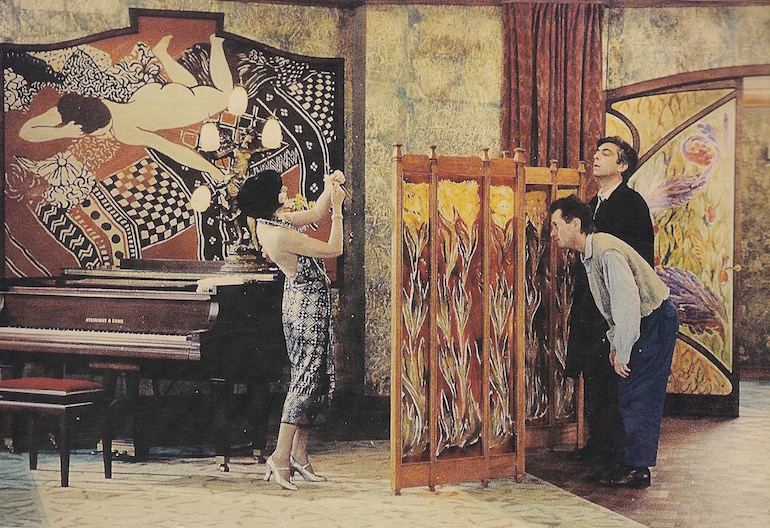

Below: Benilde ou a Virgem Mãe (Manoel de Oliveira, 1975)

But the ‘theatralisation’ of the space is not only perceived in the space of fiction that the camera constructs or deconstructs according to the vision of the spectator. Many times is the nature of the decors themselves what turns it theatrical, false (and again the nature of the film device is exposed). It is obvious that this happens in several decors of The Satin Slipper. Curiously, the least theatrical the argument is, the biggest the need of the filmmaker to use this resource: the decors of Benilde’s do not seem to be fabricated, but those of Amor de Perdição (1979) do. A Caixa is developed in a real ‘decor’. In Mon cas, if not for its expositive half oval form, the shooting of Regios’s play could almost be a real ‘decor’, but the last part, ‘The Job’s Book’, is represented in an evidently painted decor, completely anachronistic by the way. Was the scene where Ema Paiva sweeps the entrance of the church in Abraham's Valley (Vale Abraão, 1993) shot in a true ‘decor’ or was it a stage? In A Talking Picture (Un Film Falado, 2003) the Egyptian Pyramids in front of which I interpret myself with Leonor Silveira, who interprets a fictional character in the most amusing game between reality and fiction he has offered me in his many films, were filmed in the real setting (and thanks to that I have been to Cairo), do they not seem as false as in a travel agency brochure? And, do we not always find, since the first films, an ability and pleasure to ‘formalise’ the landscapes themselves or to denaturalise the natural decors through the ‘frame’? And how many times is colour itself what makes them theatrical? Can Picolli’s and Bulle Ogier’s dinning room in Belle Toujours exist in that colour? One who speaks about the decors could refer to the costumes as well, so many times evidently false as in theatre.

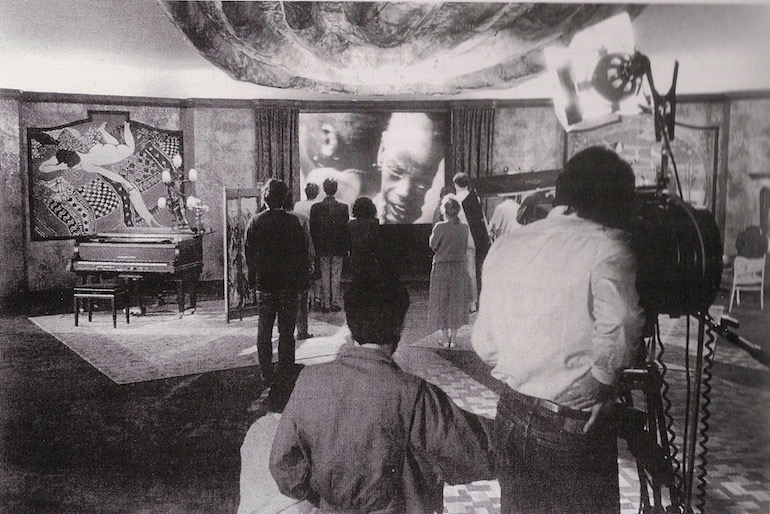

Below: Belle Toujours (Manoel de Oliveira, 2006)

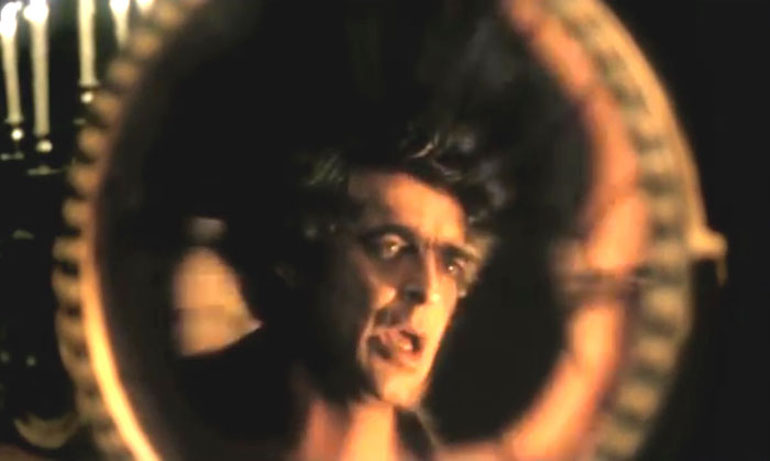

Why, if nobody complains about it in theatre, do the texts of the actors, their dialogues are believed to be artificial? Oliviera does everything, almost always, for the text not to come out ‘naturally’ from us the actors. Now with another order I have heard from him many times: ‘Speak loud!’ And this is, again, the opposite of what any filmmaker would do. They usually do whatever is possible to dissimulate that the sentences of the characters are not the actor’s or the character’s, but rather those of the scriptwriter. Oliviera yearns for seeing an ‘artificial’ way of representing in the actors because he does not want to make any illusion through cinema, and because the literary words are better, they are a product of the work of other artists. And which theatre does Oliviera incorporates to cinema? What plays does he take to the screen? Texts that are not part of the usual repertory, and are even more ‘artificial’ than what theatre usually implies. They are all particularly elaborated texts, many times laborious and very far from the spoken language, which is the opposite of what is usually considered suitable for cinema. Plays that even in theatre, where we are used to characters who speak in a literary language, could be easily considered impossible to represent: in Acto, a 16th century text based on the Bible and transformed by the tradition until the 20th century, two plays by Vicente Sanches, three by Régio, two by Prista Monteiro, one monumental play by Paul Claudel (seven-hour-verses). Oliviera constructs a cinema that is exposed as artificial but does not bring theatre to cinema, he rather turns theatre in a pure distancing artifice both through a type of non-natural diction that is usually called ‘theatrical’ and the theatre texts he choses. He invents a process. A Caixa by Prista Monteiro is fully written in a language that Prista declares to be a variation of the popular speech from Lisbon, but which actually is a very artificial dialectical pastiche. In Os Canibais (1988) he wanted the artifice to get so far that he filmed an Opera in a natural setting and he made the artists preform in playback. He deprived them from their voice, the worst of the different ‘tortures’ he had subdued me to probably believing that the greater the artifice in the way of representing, the least artifice I would be able to produce for my presence on screen and therefore would expose myself more truthfully. And behind the image of the leprous Job in Mon Cas, created on my skin by the make-up artist to the point only my eyes and mouth remained visible, behind the French diction of the Biblical texts or of Viera’s pseudobrazilian, there are, in fact, some of the moments in which I have least defended myself in front of the filming machine. But does this pleasure for making the word artificial in cinema not extent to other processes of working the texts that has nothing to do with theatre, or to for example, novel adaptations? In the sense in which this cinema is accused of theatrical, are Oliviera’s dialogues in Non or Agustina’s dialogues in The Uncertainty Principle (O Princípio da Incerteza, 2002), for instance, not as theatrical or even more theatrical than many dramatic texts? And is it only through theatre that Oliviera achieves that effect in the spectator? Would the narration of Abraham's Valley or the letters of Amor de Perdição, both effects of the novel itself transported to cinema, not have a distancing effect in the spectator or charm them with processes of more responsibility than the pure effects borrowed from theatre?

When one talks about theatre in Oliviera’s cinema, one talks about the actors too. Only when Oliviera started to work with great foreign actors or at least when he started to do it in French, maybe then, the complaints about the bad interpretation of his actors, about them being theatre actors with no cinematographic technique, false, etc., ceased. I don’t think there is any problem in the quality of the performances of Oliviera’s actors. And it is an absurdity to call ‘theatrical’ the way in which they perform, even in The Satin Slipper. In Oliviera’s cinema there is, for good and very much so, the concept of good and evil. But this would never be applicable to the actor’s performances. There are no rules for the filmed matter. No actor can ‘do wrong’ because ‘performing’ in Oliviera’s film is never a technical medium to make fiction arise, this is to say, to make the spectator forget they are looking to actors and believe they are looking to characters. Characters are never seen in his films. They might be created in the spectators’ mind, in some cases more than in others, based on the way the actors interpret their gestures and speak their dialogues. But what the camera actually records, are characters in the act of representation, as it is evident, on the other hand, in Acto. Who sees in that unforgettable Virgin Mary weeping at Christ’s feet or in the sublime Veronica, the virgin or Veronica themselves, more than two peasants of Trás-os-Montes in the act of the most moving faith? Is the subtitle with which the film was announced not ‘The village of Curalha in the rite of the Passion?’ One would say this always happens in cinema, by definition, even when the representation does not seem theatrical. Yes, but the difference is that, as opposed to a ‘normal’ or ‘normalized’ cinema, Oliviera turns that into a means of artistic expression and gives it to the spectator to see. And one would say this happens in theatre as well. No, because in theatre the representation of the actors is itself the artistic language with which the dialogue with the spectator is held, and for that to happen, an acting coherence is indispensable between the actors, in the light of which one can say some are doing good and some others wrong. In Oliviera’s cinema, the coherence of the artistic language is the look the filmmaker addresses to the actor. And nobody can do wrong. On the other hand, nobody ‘does’, they all ‘are’ just what they are (as much as a human being). And as Oliviera always does, he makes a clear affirmation about this in his cinema: when he makes Teresa Madrugada say in front of the camera who she is (Teresa Madrugada) and which the character she will interpret, Ana Plácido in O dia do Desespero (1992). Some actors might have a more interesting way of performing, that for sure, but watching how each one of them preforms and what of their deep truth as human beings sweets from there, is one of the biggest pleasures that this cinema can give us. That is why Oliviera makes it possible to get sublime moments from non-actors who in theatre would find it difficult, and less interesting moments from professional actors when they are helped by normalized or stereotyped technical media to perform. And he makes possible that great professionals, apprentices and amateurs cohabit in equal conditions and in the same film. Who will not find the non-actress Teresa Menezes as sublime as the great actress Manuela Freitas in Francisca? No, the ‘artificial’ way of acting in Oliviera’s films has nothing to do with theatre, even when we are talking about theatrical texts. Would someone believe they are seeing theatre if they saw The Satin Slipper on a stage represented as in Oliviera’s film?

The time of his films, always considered slow, is usually called ‘theatrical’ as well. Why? Is it because in theatre there is no montage of images and the time of the action is not manipulated by any intermediate between the dramatic action and the spectator? And because cinema can create a dynamic where the dynamics generated between actors, space and time of the action are manipulated by the succession of discontinuous images created by montage? Maybe, but I believe this issue is only raised because the spectator is surprised with a cinema that does not present, as usual, everything ready for passive consumption. This cinema projects itself differently and likewise demands a constant surprise. Oliviera does not have, and I believe he does not desires for, his own manner or a style. It would be rather easier to discover an attitude. But there is, in fact in many of his films, a pleasure for making the shot last the time required by the filmed action and make the filmed action last the time it demands itself, as far as it is technically possible. Because in cinema everything represents without ceasing to be what it is. And this is the opposite of the idea of cinema as a factory of illusions. It even opposes the construction of a ‘story’ by the rhythm of images, of a narrative sequence. Oliviera will rarely assume the place of the narrator. Maybe because he does not want his function as a filmmaker to be that of a manipulator of reality placed outside it to create a filter between reality and the spectator. He will be, at most, a witness or the inventor of the filmed reality itself. To manipulate the true perception of the real time of the action through illusions constructed by montage might not coincide with what I consider the purpose of his cinema. Oliviera wants to see things are they are, and maybe as they are not usually seen. He has always had, as I have understood, a documentary maker’s soul. I do not think he could ever have the gesture of manipulating the gaze of the spectator, whose responsibility he is always calling. His more recurrent process is the creation, in different paths, of a strangeness effect in the spectator, in order for the reality recorded in the image to be better apprehended or to be able to tell us more about its own reality. But he films them in the time they actually occurred, without constructing a fictional time, and because this is very rare in cinema, the result is a very slow time effect for we to perceive it with no strangeness. Opposite to what usually happens in cinema, one would say that the film is made from an amalgam of internal times of the shots seen as a whole. But is it for this reason that it is transformed into theatre? Is it time in theatre as such? I do not think so. Oliviera’s game with real time does not have the rules of theatre, he rather subverts those of cinema.

To create distancing in cinema is not only a characteristic of Oliviera. Many others filmmakers have done it and do so. But I think he believes very strongly in men to prefer the fiction constructed on reality over the human reality itself, as usually happens in cinema. The processes he uses both include theatre as one of the ways in which men represent themselves and resemble many times those of theatre, but rather than turning his cinema into theatre they make it more cinematographic. Not exactly as theatre addresses the audience of each show, but similar to this small universe, this cinema, in fact different, addresses humanity in the light of history, as one who speaks about the Son of God to all those who God created and with the degree of responsibility which it implies. A sinner’s speech to other sinners. ‘Contemplate this as any sinner’ As if said to the whole world, in the present and the future.

Below: Inquietude (Manoel de Oliveira, 1998)

But Oliviera is, in fact, closer than the majority of filmmakers to theatre in one thing. He works his imagination to invent a representation, like a theatre director, inside the image itself and before it becomes an image. His work is done, like that of the theatre actors, while he is alive and within life itself, during the shooting, like the invention of multiple live-games of figuration with the actors, the decors, the place where the lights or the camera is placed, the frame, the camera movements he invents while he is in front or by the side of the human beings he is working with. Alone during the scriptwriting, of course, inventing a project (and even then he rather works in the future than in the past), but above all inside the present while the whole team works simultaneously, in the ‘plateau’ and very little in montage, especially after discovering (in the Acto?) that cinema can represent as much as it gives to the sight, and that is possible to be while one represents, that we never stop being who we are, even when we are representing: on the contrary we live even more. The time of our lives does not stop until death. Manoel de Oliviera’s work as a filmmaker is not similar to that in which life has passed and has just remained fixed by mechanical and chemical processes. It is made at the time of the filming matter. The work is like that of theatre, although produced with more complex processes because it inserts in life a way to frame theatre cannot. And it can join sections of time. He is in fact near of what we do in theatre, living and discovering life through the work of representing it in front of other men, our brother sinners, to help them understand or demand them to understand their own human condition. Finally, Manoel de Oliviera makes his cinema as one who makes theatre. He is, in that matter as well, a Honorary Doctorate.

ABSTRACT

Based on his experience as both an actor and spectator in Manuel de Oliviera’s films, the author reflects about the relation of the filmmaker with theatre, and his way of working the space, the texts, the actors and time. From Acto da Primavera, conceived as a truly poetic art, this essay visits Oliveira’s filmography to show the way in which his films are based in documentary to reach the actor, and how artifice and representation is constructed from there as the best way of capturing the truth of a mysterious reality: the human life.

KEYWORDS

Manoel de Oliveira, theatre, actors, camera, fiction, documentary, distancing effect, space, text, time.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

TURIGLIATTO, Roberto, FINA, Simona (coord.), (2000). Manoel de Oliveira. Torino. Torino Film Festival, Associazione cinema giovani.

OLIVEIRA, de Manoel, DA COSTA, João Bénard, (2008). Manoel de Oliveira : cem anos. Lisboa. Cinemateca portuguesa-Museu do cinema.

LUIS MIGUEL CINTRA

Portuguese actor. In 1973 he founded the Cornucopia Theatre together with Jorge Silva Melo. They have staged over 100 theatre pieces. He has participated in numerous films of Portuguese cinema, especially in those by Manoel de Oliveira: The Satin Slipper (1985), Os Canibais (1988), O Dia do Desespero (1992), Abraham's Valley (1993), A Caixa (1994), The Convent (O Convento, 1995), Anxiety (1998) and Word and Utopia (Palavra e Utopia, 2000).

Nº 6 THE POETRY OF THE EARTH. PORTUGUESE CINEMA: RITE OF SPRING

Editorial. The poetry of the earth

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

The soul cannot think without a picture

João Bénard da Costa, Manoel de Oliveira

A certain tendency in Portuguese cinema

Alberto Seixas Santos

To Manoel de Oliveira

Luis Miguel Cintra

The direct experience. Between Northern cinema and Japan

Paulo Rocha

Conversation with Pedro Costa. The encounter with António Reis

Anabela Moutinho, Maria da Graça Lobo

ARTICLES

The theatre in Manoel de Oliveira's cinema

Luis Miguel Cintra

An eternal modernity

Alfonso Crespo

Scenes from the class struggle in Portugal

Jaime Pena

Aesthetic Tendencies in Contemporary Portuguese Cinema

Horacio Muñoz Fernández, Iván Villarmea Álvarez

Susana de Sousa Dias and the ghosts of the Portuguese dictatorship

Mariana Souto

REVIEWS

MARTÍNEZ MUÑOZ, Pau. Mateo Santos. Cine y anarquismo. República, guerra y exilio mexicano

Alejandro Montiel