PRESENCE (APPEARANCE AND DISAPPEARANCE) OF TWO BELGIAN FILMMAKERS

Imma Merino

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Agnès Varda (1928) and Chantal Akerman (1950-2015) were born in Brussels twenty-two years apart, which, evidently, makes them belong to different generations and –with their connection to French cinema and culture– take part in the development of cinematic modernity in different ways. Varda is a Nouvelle Vague pioneer and, at the same time, being a woman amongst men, an outsider in the movement until her late appreciation. Akerman is a Nouvelle Vague heir who practically always made cinema from the sidelines. Each one in her own way –with notable stylistic differences– has thought about the fact of being a woman (and about women’s bodies) to show the female alienations and liberations, has diluted the limits between documentary and fiction to invent her own formats and, amongst other aspects and in relation to the matter at hand, has made herself physically present in her images, where there are also personal traces through fictional characters and the filmmaker’s narrative and reflective voice. Curiously, though, we can observe an inverse process: while Varda has progressively made herself physically present in her images, Akerman’s body increasingly became invisible expressing that presence through her voice.

In the notable year of 1968, Chantal Akerman burst into cinema like an explosion that, even with a minimal scope, has had delayed and long-lasting effects. It was with Saute ma ville (Blow Up My Town), a short film that ends with a literal explosion, where an oven bursts into pieces, belonging to a young singer with a ‘Chaplinesque’ attitude (Akerman herself) who clumsily carries out a series of domestic activities, which, in this way, are subverted in relation to the assigned female roles. It is a literal explosion, but with a symbolic dimension –in 1968 it is a gesture that appeals to a will of destruction as the possibility to build something new. Likewise, due to Akerman’s death and the suicidal pulse that is glimpsed in this first piece where the alternation between vitality and depression –so common in the director’s filmography–is traced, the explosion seems to have acquired a premonitory sense in an uncertain terrain between the literal and the symbolic. In any case, part of the singularity of Saute ma ville has to do with the fact that the filmmaker herself comes into scene.

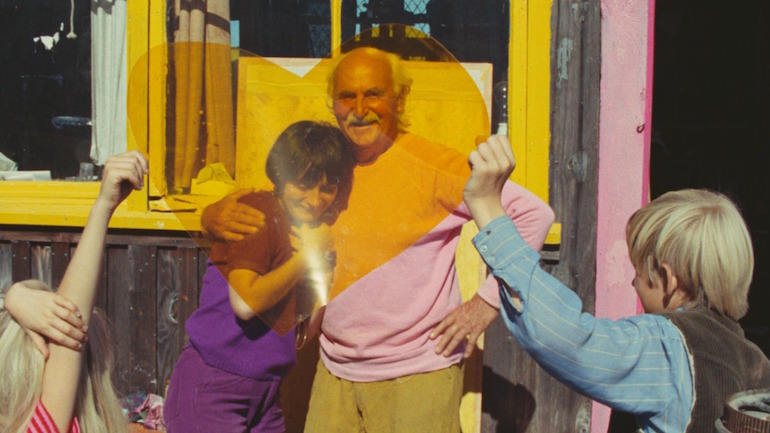

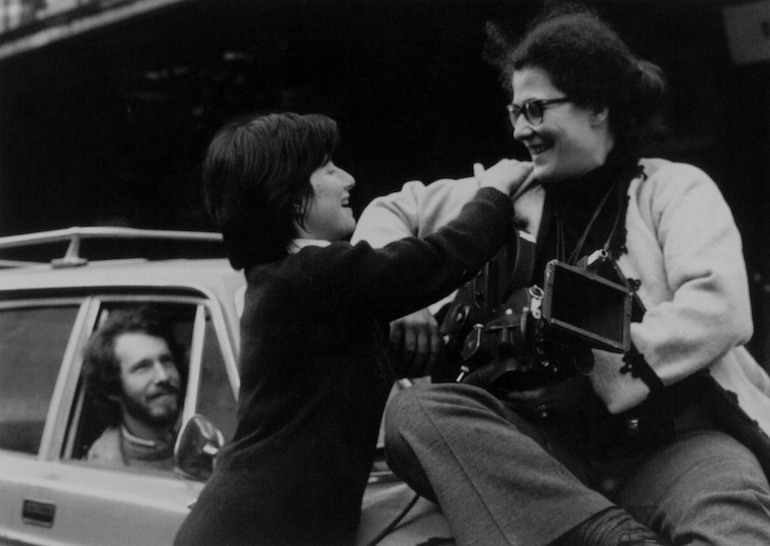

A photographer that started making cinema in 1954 with La Pointe Courte, a film set in a fishermen’s neighborhood of Sète that traces the becoming of a filmography between realism and artificialness or between life and its representation, Agnès Varda made herself physically present in her images for the first time a year before Chantal Akerman. Before that, sharing the voice-over narration with Michel Piccoli without highlighting the subjectivity, she had left a carnal trace with her voice in Salut les cubains! (1963), a montage of the animated succession of photographs shot in Cuba in the first years after the revolution and, therefore, while the Castrist regime was being established. In any case, in the year 1967, Varda physically appeared for the first time in her cinema with Oncle Yanco (Uncle Yanco), a short film in which, from the story of an artistic uncle who lived as an old hippie on a boat in Sausalito, she explored her own identity searching in a Californian harbor for her father’s hidden Greek roots, which he had never spoken about. The filmmaker appears occasionally in the shot as if she wanted to keep the newly found uncle company and, at the same time, as if she wanted to make a physical record of the personal search of her origins. But there is also the ‘modern’ gesture of making the cinematic device visible (while having lunch with a group of people, she asks that they ‘cut’ the take) and of showing the possible existence of representation in the documentary: the film, with the presence of the clapperboard, starts with the repetition of a scene in which Varda and her uncle Yanco reproduce the moment of their encounter. Two years later, while the filmmaker lived in Los Angeles and had started her own projects after having arrived accompanying Jacques Demy in the adventure that brought him to film Model Shop (1969) for Columbia Pictures, the gesture of cinematic modernity seems to be more conscious with Lion’s Love, a hippie fantasy with Viva and the creators of the musical Hair (James Rado and Gerome Ragni), which, by its own artificial character, is at the same time a document about the Hollywood of the time. The thing is that there is a scene in which, next to a camera, Varda is reflected in a mirror that, since Cléo de 5 à 7 (Cléo from 5 to 7, 1962), had turned into a recurrent object in her cinema, inhabited by reflections, duality, changing identities, the tension of realness and its representations. Moreover, there is a curious sequence in Lion’s Love that, following what Varda has explained1, refutes certain assumptions. In this sequence, the independent filmmaker Shirley Clarke2, a possible North American double of Varda, seems ready to commit suicide because her Hollywood producers do not grant her the final cut and, therefore, the freedom of making her own film. Suddenly, Clarke says: ‘I’m sorry, Agnès, but I’m not an actress and cannot pretend I’m taking the pills.’ She adds that she would never commit suicide for a movie. Then, Varda furiously comes into scene telling her that, if she doesn’t do it, she will do it herself. Is Varda’s intrusion an act? A game? An action to create distance from fiction? Varda claims that her intrusion was not premeditated and that it was not even improvised. Simply, it happened; the camera continued filming and Varda decided to include it in the final cut as a record of a moment where Shirley Clarke did not participate in the game of fiction and in which a filmmaker intercedes to demand what was agreed to another filmmaker who, curiously, made films with a documentary appearance. Strange sequence.

Expressing her own subjectivity through her voice-over both in essay documentaries (in a special way in Ulysse, an extraordinary short film from 1982 in which she questions the memory from a photograph taken many years before in an Atlantic French coast beach where we can see the back of a naked man, a child sitting amongst the rocks and a dead goat) and the fictions L’une chante, l’autre pas (One Sings, the Other doesn’t, 1977) and Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond, 1985) leaving proof that she is the narrator, Varda did not appear in the image again until twenty years after Lion’s Love. This was in Jane B. par Agnès V. (1988), which is insinuated as a portrait of actress and singer Jane Birkin, who constantly appears disguised as a different array of characters3. Varda appears occasionally from a very elaborated sequence in which Jane Birkin is in front of a mirror while we hear Varda’s voice-over: ‘It is as if I filmed your self-portrait. But you won’t always be alone in the mirror. There will be the camera, which is a part of myself, and who cares if I sometimes appear in the mirror or in the field of vision.’ While she says these last words, the camera turns around and, next to Birkin, the filmmaker appears in the mirror after the camera has also been made present in a new gesture of the conscious cinematic modernity. The game of representation and self-representation becomes visible. In any case, it is interesting that Jane Birkin herself considers that, in Jane B. par Agnès V., there is less of a portrait of herself than a self-portrait of the filmmaker through the stereotype she embodies4.

Not often has a hand stroking a back made the love of a person to another so visible in a cinematic image as Varda’s in Jacquot de Nantes, a 1991 film in which the filmmaker reconstructs Jacques Demy’s childhood and teenage years; but Demy also appears in the latter months of his life, and the camera captured the imprint of his sickness in his body, following the surface of his skin full of spots: a way of retaining him in the images, of resisting death? The filmmaker has said that it was her way of keeping him company. After Demy’s death, Agnès Varda dedicated herself to his memory with two more films where he is also present in the images: L’univers de Jacques Demy (The World of Jacques Demy, 1995), participating as one of the witnesses who remember the filmmaker, and Les demoseilles ont eu 25 ans (The Young Girls Turn 25, 1993), in relation to the celebration of the 25th anniversary of Les demoiselles de Rochefort (The Young Girls of Rochefort, 1967) at the town where it was filmed. They are two films in which the viewer is directly addressed for the first time, situating herself directly in front of the camera’s lens. In this same position, but with a shyness that doesn’t allow her to look the camera in the eye and, therefore, the viewer, Varda reveals what might be her biggest confession in the interior of her cinema. It is in Deux ans après (The Gleaners and I: two years later, 2002), sequel of Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (The Gleaners and I, 2000), a documentary with a great impact with which she portrays an array of people who scavenge things (the ‘glaneurs’) and herself (‘the glaneuse’) as a gatherer of images. In her confession in Deux ans après, Varda admits that she had not noticed that, in the prequel, she had filmed her hands, with spots and other imprints of old age, in a similar way as she had filmed Demy’s skin in Jacquot de Nantes. She explains that this was suggested by critic Philippe Piazzo: ’Everyone had seen this except me. And I don’t want to come across as an idiot or naïve, but it impressed me how much one can work without knowing. One doesn’t work in the meaning and continuity. They tell me that my cinema is very coherent. They can say what they want, obviously, but the thing is I work as I can.’ Her conclusion: ’On ne sait jamais ce qu’on filme (you never know what you’re filming).’

It is with Les glaneurs et la glaneuse that, apart from being present in her voice-over comments, Varda decidedly physically appears in her images. Nevertheless, she only appears in four minutes of the total eighty minutes. Although what is predominant is the portrait of an array of modern gleaners that define the social theme of the film in relation with a consumer society that throws things away while others pick them up to survive, Varda’s presence had her accused of narcissism and impertinence, for example by one of the glaneurs (Alain F., who feeds himself with the markets’ leftovers while he survives selling a magazine and, selflessly, teaches evening lessons to immigrants) who, in Deux ans après, blames her of not being in accordance with the film’s theme. Varda replies that she is also a gleaner (of objects, but mostly of images) and that she filmed herself for honesty: just like a portrait, she had to honestly be exposed in front of the camera. In any case, contradicting Alain F., Varda’s body is not an impertinence in the film, it is relevant. While she filmed a hand, which held a postcard that reproduces Rembrandt’s self-portrait, with her other hand, she realized there was a bright relationship with one of the film’s themes: the passing of time and its imprint in things and bodies. Integrated these images in the film, the self-portrait is a representation of the world while the portrait of other bodies and objects becomes a self-portrait. This statement from Italian philosopher Franco Rella comes to mind: ‘The representation of the world becomes a representation of itself, the portrait (of a face, but also of a thing or a scene) becomes a self-portrait. To show the world in its change means to show the world in the change itself, to the point that, as Baudelaire says, the self evaporates or, as Rimbaud says, the self becomes someone else’ (RELLA, 1998: 58).

A Serge Daney’s theory also comes to mind, which he expressed in an article published in Libération on the 24th of January of 1982 in relation to the diptych formed by Mur Murs (Mural Murals, 1981) and Documenteur (1981), which Agnès Varda filmed at the beginning of the 1980s during her second stay in Los Angeles. Mur Murs is an outgoing documentary about the muralism in Los Angeles and Documenteur is an introverted film in which, also with the presence of murals, a woman (with a child interpreted by Mathieu Demy, the son of Demy and Varda) lives in pain and strangeness after separating from her husband: a way of self-portraying herself through an interposed character (and the presence of editor Sabine Mamou) in a moment of crisis and, actually, of separation of the couple. In Daney’s article, he mentions that, in relation to the hypothetical discovery of the mix between fiction and documentary, this has always existed in cinema. He adds that, in fact, every film is a ‘document’, which he argues with revealing intuition: ‘“A documentary, remember that, was always on something. It weighed over the sardines, the shepherds, the plebs, the orchids, the Fidji islands, the fishermen, the colonies, the others, Whereas a document is with. A document informs about the state of the matter which is being filmed or will be filmed, and about the filming body as well. One with the other. A film/document such as Les glaneurs et la glaneuse certainly informs about the state of the matter that it films and about the state of the body that films.

In showing the postcard of Rembrandt’s self-portrait, Varda says: ‘Here we have Rembrandt’s self-portrait. It is always the same, a self-portrait.’ And then she covers the postcard with her hand. Isn’t this a way of suggesting that any self-portrait shows and at the same time hides? Some years later, with Les plages d’Agnès (The Beaches of Agnès, 2008), Varda becomes omnipresent in the film because she herself is the topic of the film, where she remembers her own life. The self-portrait takes the temporal dimension of the autobiography, an unusual genre in cinema. Nevertheless, although showing herself and remembering her life, there is a warning at the beginning of the film. In a beach, she sets up an installation of mirrors while the wind makes her scarf cover her eyes. Laughing, she tells her assistants that this is her idea of a self-portrait: some deformed mirrors and a scarf over her face. Apart from the images filmed in the present with her physical presence and her comments, the filmmaker uses in Les plages d’Agnès her own filmography, as well as photographs and other documents and objects, as if it were an archive, as a form of memory that, through selected fragments, lets her evoke different moments of her life and her times. At the same time, it is indicated that there are biographic elements transformed in fiction material and embodied in characters that act as doubles or as more or less deformed mirrors. In a certain way, it reminds me of the game of Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman (Chantal Akerman by Chantal Akerman, 1996), the film for the series Cinéma, de notre temps in which Akerman presents as a possible self-portrait (and also an autobiography) the chaining of different sequences of her films, which shape a formal research between fiction and documentary, diary and essay. Akerman, though, mostly uses fictions, which makes it even more interesting and complex in relation to the multiple ways of self-portraying herself. In this way, as Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman suggests, the filmmaker would represent or split herself differently in characters embodied by Aurore Clément (like in Les rendez-vous d’Anna [The Meetings of Anna, 1978] in which a filmmaker travels from the German city Essen to Paris), in the starving Maria de Medeiros of J’ai faim, j’ai froid (1984) or in the girl that wanders through Brussels discovering her sexuality and feeling lonely in Portrait d’une jeune fille de la fin des années 60 à Bruxelles (Portrait of a Young Girl in the Late ‘60s, in Brussels, 1993). The idea of the splitting identity is clearly addressed in Lettre d’une cinéaste (1984), one of the filmic letters with which different filmmakers responded to a request by Cinéma, cinémas, a television program of the French Antenne 2 channel that was broadcasted from 1982 to 1991. In this eight-minute filmic letter Akerman confesses that she makes cinema because she hasn’t dared to try writing, although it is essential for her creative process: ‘To make a film, one always needs to write.’ To write to clarify what one wants to film; to write to choose, elaborate, order the experience; to write to think, to understand the world and oneself. Chantal Akerman turns her Lettre d’une cinéaste into a kind of humorous self-portrait in which she explains what one has to do, apart from writing, to make a film: get up, get dressed, eat, have actors and a team at hand. But not only in her case, but also in the case of actress Aurore Clément, so that the idea of splitting identity, of the (self) representation through actors is addressed.

Nevertheless, we can consider that Akerman did not only split or project herself in characters embodied by actresses. She herself played fictional characters, although it is possible to question ourselves if these characters are a representation of her or a way of becoming someone else. I have talked about Saute ma ville. Eight years later, in Je, tu, il, elle (I, You, He, She, 1974), she made herself physically visible in the images to narrate the journey of an experience that starts in solitude, while she writes and eats sugar in an apartment, passes through the contact with someone else (the truck driver played by Niels Arestrup) and finishes with the reencounter with the body of another woman to represent female sexuality in an alternative way: a final and long scene in which, contradicting the ‘voyeurism’, two naked bodies embrace and rub against each other with a frankness and crude sobriety contrary to pornographic cinema. In any case, does Akerman represent a character named Julie? Or does she represent herself? Maybe both. After all, the presence in an image of a body (something which also applies to the actors) is in itself a form of self-representation. As, on another hand, in a self-representation there can be a game with oneself, a disguise, a desire of being someone else or inventing oneself.

Contrary to Varda, who has made herself more visible in her images with the passing of time, Akerman has become physically invisible in her cinema, although she sometimes reappears, such as in L’homme à la valise (The Man with the Suitcase, 1983), which, as if it were a self-fiction in which she herself is in an imaginary situation, welcomes us to contemplate what aspects of Akerman herself are in a character that, after two months of absence, returns home with the need to work (indeed, in a meaningful way, she wants to write) and finds that the friend to whom she has lent her apartment to does not want to leave. Or such as in Portrait d’une paresseuse (1986), in which, in her bed, she lays at the feet of her beloved Sonia Wieder-Atherton to listen how she plays the cello. In any case, even if she doesn’t appear physically, her personal and biographical imprints are present in her films, always in the search of new ways.

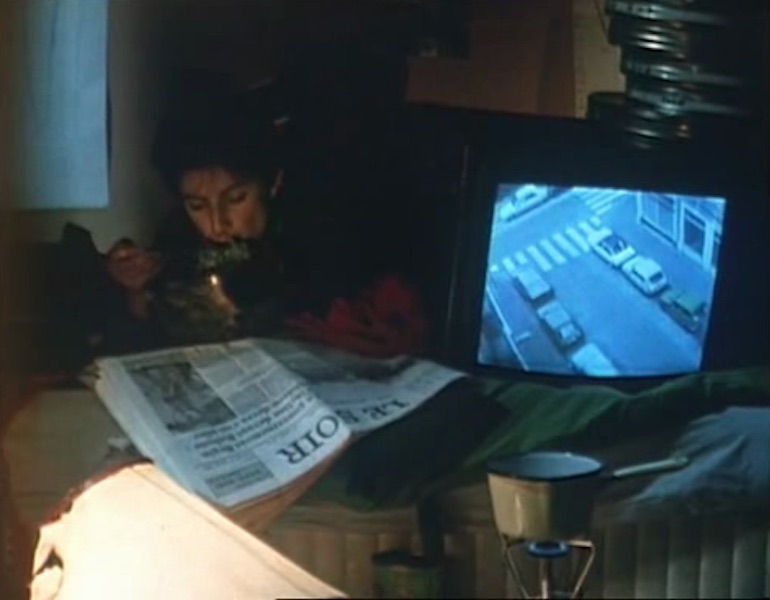

In fact, the physical absence together with her full presence soon came with News from Home (1977), in which she herself reads the letters she received from her mother, Natalie, during her stay in New York in 1973. It was the filmmaker’s first stay in this city. Three years later, in 1976, she returned to film the images of News from Home. Akerman revisited the places she knew from her previous solitary walks around the city, before filming only 170 minutes for a film that lasts 80 minutes. The memory and reflection of the lived experience had done their work. Once time had passed, the memory of the spaces revealed what was the precise place where the camera had to be set up to reveal a personal gaze linked to a feeling of alienism (and at the same time the wish of knowledge of an alien reality) which is also perceived in some of her later films, filmed either in Eastern Europe, in the American South, in either side of the border between Mexico and the U.S. or even in Tel Aviv.

After time had passed, Akerman, who had always rejected sentimentalism so that a deeper emotion could appear, read her mother’s letters with a distance thatallows to communicate the experience: we can recognize her wish of her daughter being happy, but at the same time the longing for the ‘prodigal’ daughter and even reproaches because she doesn’t write back, the insistence that she take care of herself, that she don’t wander about dangerous neighborhoods and don’t go out at night. Time passes and mothers do not change. Maybe neither do the daughters. Thirty years later, during the filmmaker’s stay in Tel Aviv while filming Là-bas (Down There, 2005), Natalie Akerman, now by telephone, still tells her daughter that she misses her, that she should take care of herself and be careful. Chantal, conscious of her mother’s restlessness due to the possible attacks, wants to calm her down: ‘I don’t take the bus, I don’t go to supermarkets or to the movies.’ In Là-bas, a film close to the filmic diary, we don’t see Chantal Akerman’s body. We observe what she sees and films from the window of her apartment in Tel Aviv. She also reveals her thoughts. In this way, while we glimpse the neighbors, she expresses that it reminds her of her past: she remembers herself as the girl who watched other children playing ball in the streets of Brussels. She watched through the window and withdrew into herself. She continues to do that. To look at others, to observe the world and withdraw into herself living the ambiguity of a state that brings solitude but also creation. The secluded and open self behind the window.

Between News From Home and Là-bas, intimate and essay-like films in which the relationship with her mother in the distance is present, Chantal Akerman went searching for her roots in Eastern Europe to show it in the silent images of D’est (From the East, 1993), with her majestic lateral tracking shots; she expressed the state of her body, even if it is not visible, through her musical but at the same time hoarse voice (due to the passing of time and maybe the effects of tobacco) in such personal documentaries such as Sud (South, 1998), filmed in the still racist American South, and De l’autre côté (From the Other Side, 2002), in which she explores both sides of a section of the border between Mexico and the United States filming a wall that reminds us of the fence of Nazi concentration camps. When Akerman went to Barcelona in the year 2006, invited by the MICEC (the International Contemporary European Film Festival), I asked her if these images of the wall had been filmed thinking of the fences of concentration camps, of which Natalie Akerman was a survivor. She answered yes, with the conviction of something that is evident, and that they were also filmed so that the viewer would think about it. There is another film, the last one, that we need to address: No Home Movie (2015), in which Natalie Akerman’s survivor state is present as much as the difficulty of speaking about this experience of maximum horror. The mother (who in some way inspires the body language, related with the repetition of domestic activities, of the protagonist of the masterpiece Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles [Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels, 1975]), occupies the center of No Home Movie and, unlike other occasions, her face and body are present, while her daughter practically does not appear in the image. The latter, as a daughter and a filmmaker, considers how to film her mother in the moment that the decay of her body announces that the transition to death is imminent. Then, the camera adopts a modest distance while the framing encloses the apartment with the feeling that it is a full space that is being emptied of life. This is the last film, so decidedly premonitory that it finishes with the curtains closing. It is not only the end of the mother but it also announces the death of the filmmaker herself, of whom we can feel in No Home Movie a vital apathy. Or maybe we know this through her suicide, which arrived a few months after the film. In the end, even with her self-portraits and biographic imprints, what can we know about Varda and Akerman through their cinema? Let’s remember the ending of Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman: ‘My name is Chantal Akerman and I was born in Brussels. And that’s the truth.’ The rest is maybe the work of our suppositions and our imagination: a self that shows itself, also hides.

FOOTNOTES

1 / In the seminar ‘Le cinema mis en question par une cinéaste’, which she gave from the 10th to the 15th of October of 2011 as a visiting professor for the Ferrater Mora Chair of Contemporary Thought of the University of Girona.

2 / Shirley Clarke (1919-1997) founded the New American Cinema Group with Jonas Mekas. When Varda included her in Lion’s Love, so that she could embody a New Yorker independent filmmaker who argues with Hollywood’s producers, Clarke had made some impactful films, such as The Connection (1962), which shows a group of heroin addicts in an apartment in New York City while they wait for the dealer’s arrival. With the unclean and unkempt texture of the images, it has a documentary’s appearance, or the one of a sample of cinéma vérité, but it is a fiction written and planned by Jack Giber, who adapted one of his theatrical plays. Both filmmakers share the fact of questioning the language and the limits of documentary and fiction, as well as a sense of independence for which Varda had similar problems in Hollywood to Clarke’s (acting both as herself and as a fictional character) in Lion’s Love.

3 / In an interview with Jean-Claude Loiseau published in the 132nd issue of the magazine Première, in March of 1988, Agnès Varda explains: ‘In this portrait, she was not in a state of confidence but representing. For me, she appears as mysterious as before the film.’

4 / In an interview with Jane Birkin, by Paloma Gil and Imma Merino, published in the magazine Presència on the 3rd of July of 1994, the actress mentions: ‘In her film there are many more things about her than of myself. It is more her own portrait. I have given more of myself through some fictions, I have reflected myself more (en aquesta frase caldria afegir alguna cosa que indiqués que aquesta major reflexió s’ha produït en les ficcions de què estem parlant – una traducció del pronom feble “hi” de l’original; tal com està ara la frase queda molt deslligada). Although possibly I ended up giving what the director wanted of me and what happens is that you end up being just like she sees you (aquesta frase sona una mica estranya i cal canviar el “he” per “she”; potser podria ser “you end up being just like she sees you”).’

ABSTRACT

Agnès Varda and Chantal Akerman are two filmmakers that, within film modernity, have invented their own rules and experimented with new ways of representation, without disregarding the fact they are making cinema from their experience as women. Each one in her own way, in her own images and sounds, has introduced her subjectivity and has become physically present through her body and her voice. Akerman burst into cinema in 1968 with Blow Up My Town (Saute ma ville), an explosive short film where she self-represented or maybe self-fictionalised; that was an attempt she continued later on, both by performing in her own films and by being embodied by other actresses, thus turning physically more invisible; meanwhile, in her more intimate, essay-like and even documentary films, her presence sometimes manifested through forms of absence, as it is shown in her last film, No Home Movie. We can also find Varda’s doubles in her last fiction films, whereas in her essay documentaries the filmmaker’s body has become more visible, acknowledging a subjectivity she had previously expressed through her narrative and reflective voice. The culmination of this physical presence is found in The Gleaners and I (Les glaneurs et la glaneuse, 2000), a documentary which links portraits of gleaners from contemporary world with the self-portrait done in the old age, and the autobiographical movie The Beaches of Agnès (Les plages d’Agnès, 2008).

KEYWORDS

Self-portrait, self-representation, body, double, documentary, mirror, subjectivity.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AKERMAN, Chantal (2004). Autoportrait de Chantal Akerman en cinéaste. Paris. Cahiers du Cinéma-Centre Pompidou.

DANEY, Serge (1982). Mur, murs et Documenteur. Paris. Libération.

GIL, Paloma, MERINO, Imma (1994). Entrevista a Jane Birkin. Girona. Presència.

NAVACELLE, Christine de, DEVARRIEUX, Claire (1988). Agnès Varda: Cinema du Réel. Paris. Ed. Autrement.

PIAZZO, Philippe (2000). Agnès Varda, glaneuse sachant glaner. Paris. Le Monde-Eden

RELLA, Franco (1998). Confins. La visibilitat del món i l’enigma de l’autorepresentació. València. Edicions 3 i 4.

VARDA, Agnès (1994). Varda par Agnès. Paris. Cahiers du Cinéma/Cine-Tamaris.

IMMA MERINO

Imma Merino (Castellfollit de la Roca, 1962). Degree in Philosophy from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) and a PhD in Communication from the Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF) with the thesis Subjectivity and selfrepresentation in Agnès Varda cinema. She teaches Film History at the Universitat de Girona (UdG) and Creative Documentary at the UPF. Works as a film critic and cultural journalist for the newspaper El Punt-Avui. She has worked in various anthologies, including Al otro lado de la ficción: trece documentalistas españoles, Derivas del cine contemporáneo and monographs on Jacques Demy, François Truffaut: el deseo del cine and Max Ophuls: carné de baile.

Nº 8 PORTRAIT AS AN ACTRESS, SELF-PORTRAIT AS A FILMMAKER

Editorial. Portrait as an actress, self-portrait as a filmmaker

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

About the femenine

Maya Deren

About Fuses

Carolee Schneemann

Conversation about Wanda by Barbara Loden

Marguerite Duras and Elia Kazan

About the Film-Diary

Anne-Charlotte Robertson

Nothing to say

Chantal Akerman

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

About the Women Film Pioneers Project

Alejandra Rosenberg

Medeas. Interview with María Ruido

Palma Lombardo

VIDEO ESSAY

Florencia Aliberti, Caterina Cuadros and Gala Hernández

ARTICLES

Lois Weber: the female thinking in movementWeber: the female thinking in movement

Núria Bou

‘One must at least begin with the body feeling’: Dance as filmmaking in Maya Deren’s choreocinema

Elinor Cleghorn

Nothing of the Sort: Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970)

Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin

The Trouble with Lupino

Amelie Hastie

Presence (appearance and disappearance) of two Belgian filmmakers

Imma Merino

Identity self-portraits of a filmic gaze. From absence to (multi)presence: Duras,Akerman, Varda

Lourdes Monterrubio Ibáñez

REVIEW

Jorge Oter; Santos Zunzunegui (Eds.) José Julián Bakedano: Sin pausa / Jose Julian Bakedano: Etenik gabe

María Soliña Barreiro