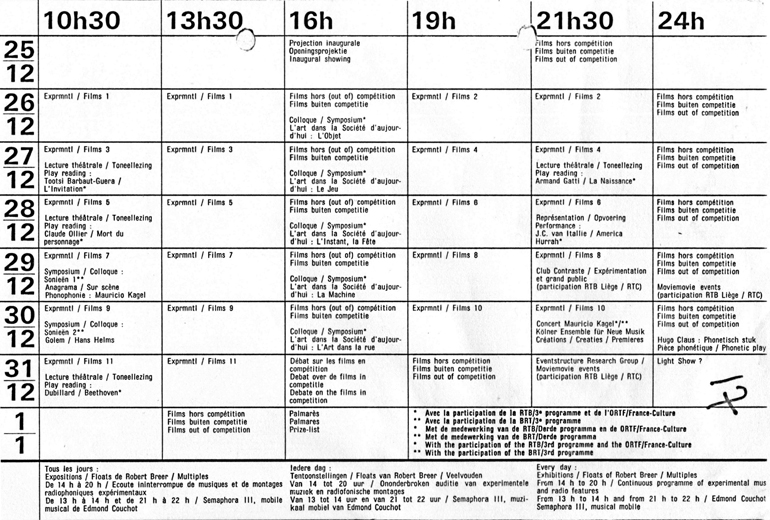

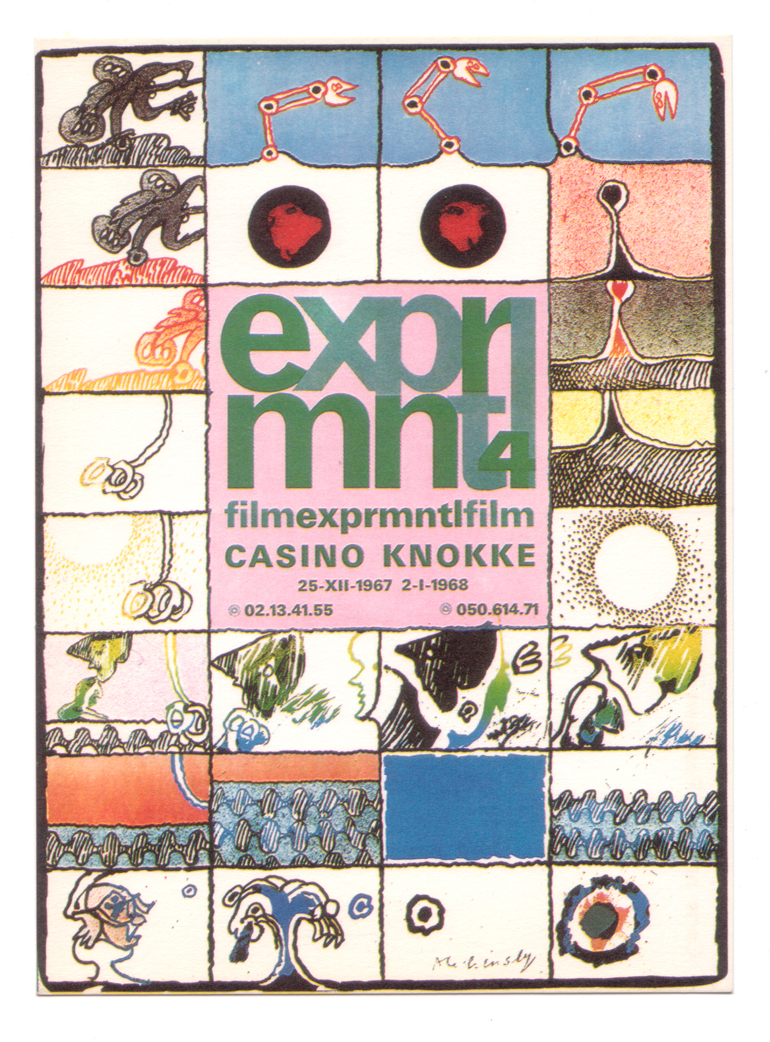

EXPRMNTL: AN EXPANDED FESTIVAL. PROGRAMMING AND POLEMICS AT EXPRMNTL 4, KNOKKE-LE-ZOUTE, 1967

Xavier Garcia Bardon

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

‘For once I was ahead of Godard: at the start of the year we interrupted an experimental film festival at Knokke, in Belgium, but, fortunately, not the films of Shirley Clarke and Michael Snow.’1 In 2009 Harun Farocki recalled the intervention he took part in, while he was a film student, at the fourth edition of the international experiemental film festival at Knokke-le-Zoute, summing up, fourty years later and just in three sentences, what 1968 meant for him.

Towards the end of December 1967, along with other students from Berlin and Ulm, drawn like him to emerging film trends, Farocki had begun the journey to this spa on the Belgian seaside, which was deserted in the middle of winter. There, over the course of a week spent by the sea, within the odd context of a casino crowded with hundreds of film-makers and avant-garde artists, visionaries, cinephiles, curious bystanders and hippies, EXPRMNTL 4 considered the state of experimentation in cinema and the arts.

EXPRMNTL, organised by the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique and conceived by Jacques Ledoux, its curator from 1948 until his death in 1988, had only had three previous editions. The first one, in June 1949, attempted to put together the first complete retrospective of all avant-garde films made since the invention of cinema, from Oskar Fischinger to Norman Mclaren, from Charles Dekeukeleire to Maya Deren, from Joris Ivens to Kenneth Anger. The second one (the first one that was actually called EXPRMNTL), was organised in 1958 within the context of the Brussels universal exhibition; it let the world discover the early films of Agnès Varda, Jean-Daniel Pollet, Walerian Borowczyk, Roman Polanski, Peter Kubelka and film-makers who would soon be referred to as underground, such as Stan Brakhage, Stan VanDerBeek, Shirley Clarke or Robert Breer. The third edition, in 1963, established the set up that would make the event become the stuff of legends: held between Christmas and New Year in the Knokke-le-Zoute casino, it brought together film-makers but also musicians, writers, researchers and artists from all disciplines into the heart of a programme that even today amazes due to its breadth, and for the vision which Ledoux tried to inspire it with. For Ledoux, avant-garde film couldn’t be placed separately from parallel, formal projects in the other arts: it could only be understood in relation to music, literature, the visual arts, and only at the heart of a network linking all these disciplines.

Along screenings of films by Gregory J. Markopoulos, Henri Chopin, Ed Emshwiller, Takahiko Iimura, Ferdinand Khittl or Edmond Bernhard, the festival held a day-long event dedicated to electronic music. Contributors included the Groupe de Recherche de l’ORTF (Ferrari, Parmegiani, Bayle) and the electronic music studio from Cologne’s Westdeutscher Rundfunk; a concert with works by Maderna, Boulez and Stockhausen; an exhibition of works by the Groupe de Recherches d'Art Visuel de Paris (Le Parc, Sobrino, Morellet) and debates with writers associated with the nouveau roman (Duras, Pinget) and with the magazine Tel Quel (Baudry, Sollers), but also with researchers, such as Lucien Goldmann and Nicolas Ruwet. In the same edition, the clandestine screenings of Flaming Creatures (Jack Smith, 1963), a film cursed by EXPRMNTL 3, which had been excluded from the contest and was projected by Jonas Mekas, P. Adams Sitney and Barbara Rubin in their hotel rooms, would for the European audience mean the discovery of underground cinema – for its aesthetic and its strategies of distribution.

Up until then, every edition of the festival had brought together an international panorama of the most striking contemporary happenings, and EXPRMNTL 4 went even further. It crystalized like few events the energy and the preoccupations – aesthetic, cultural and political – of a time. In a document dated 1974, Ledoux unveiled, later on, the key to his programme: ‘There are three parts to the festival: first, the film competition, second the non-film related activities, third the unexpected. The first and the second lead to the third.’2 The strength of EXPRMNTL lies in the articulation of these three parts, the ‘secret’ of this open construction whose complexity has been remarked upon by several witnesses.

To begin with, let’s be precise: just as everyone who collaborated with Ledoux agrees about his thorough attention at all stages of conceiving and organising a project (not to mention his tyrannical nature),3 when Ledoux is discussed within the context of EXPRMNTL, as Jean-Marie Buchet recalls, ‘it’s important not to forget that we’re talking about a collective institution, which he’s only the head of (but consequently also the face to).’4 If Ledoux certainly decided everything down to the minutest detail, this was because a collective all around him nurtured his thoughts and let him develop the event. Long-term accomplices René Micha, Paul Davay, Yannick Bruynoghe and Dimitri Balachoff (critics all of them, passionate about cinema and culture, but also artists) made up this programming team hovering around Ledoux, which helped him in all aspects of the project, from fundraising through planning events outside the screenings, and also with the film selection process.5

The first part of the programming process involved choosing the venues. A completely deserted bourgeois spa, over the Christmas holidays Knokke-le-Zoute seemed like a ghost city, a backdrop conjured up for an unlikely situation. This abstract world-and-time-bubble was all about mixing subjects, and asked anyone interested in going to the festival (between two and three thousand people in 1967) to submit to a total immersion experience, over a week, without a break. Facing the sea, the casino was a space to inhabit and reinvent. But EXPRMNTL was also what it was thanks to the relationship between the president of the film archive, Pierre Vermeylen, a diplomatic and influential person,6 with Gustave Nellens, the casino’s director. An art collector (with a penchant for surrealist Belgian painting, shown by the Magritte and Delvaux frescoes that decorate the walls of his venue), Nellens offered his casino and staff to the festival.

Looking through the list of films in the competition, what’s striking is the wide understanding of the term ‘experimental’, which the organisers juxtaposed a wide range of projects around. According to the regulations of the competition, ‘the term “experimental cinema” would be understood to comprise all works made for film or televisión, which would show evidence of trying to regenerate or widen film as a medium for cinematic expression’.7 A third of the selected films are American, but EXPRMNTL 4 is not satisfied with giving a seal of approval to the underground canon. The programme presents (and sets in tension) a great variety of projects, in which experimentation can exist both formally and as a background, or as a way of dealing with a topic: pre-structural films, surrealist essays, poetic documentaries, humorous animations and animated collages, dance films and even an erotic feature in Cinemascope.

Ledoux insisted on the exclusive nature of the films in the programme: save for a few exceptions, the competition was strictly reserved for works that had not previously been screened, which meant risking not including films whose importance, however, was already agreed.8 Here is where the organiser’s genius came into play. To promote the creation of new works, the festival became a producer. Ledoux worked out an agreement with Agfa-Gevaert which meant that the Cinémathèque would receive a considerable amount of 16mm film, to be given to a hundred film-makers, who’d agreed to use it. Actually, in this inspired gesture there’s ‘a mixture of calculation and generosity’.9 ‘Generosity’: Ledoux offered straightforward and concrete assistance to out-of-pocket film-makers. ‘Calculation’: he ensured, at the same time, that the films shown at Knokke would be original. Among the 59 films made with the stock given by the festival and submitted to the selection jury are projects by Marcel Broodthaers, Martin Scorsese, Jean-Jacques Lebel, Piero Heliczer, Jud Yalkut and Werner Nekes, as well as of course a large number of unknown artists, whose names have not been preserved by history. Twenty-four of these films would be chosen, to which 66 others would be added. In total, the competition was made up of ninety films, distributed among 11 programmes, which were each presented twice a day.

Ledoux continued developing the festival by choosing the competition jury. Shirley Clarke, Vera Chytilova, Walerian Borowczyk and Edgar Reitz were the jury for EXPRMNTL 4.10 Each of them had already taken part in at least one edition of the festival. They knew its spirit. Ledoux worked to build an international community, careful to make sure there’s a balanced representation of various trends and understandings of what ‘experimental’ means. This jury gave the main prize to Wavelength (1967) by Michael Snow, and special awards to films by Lutz Mommartz (Selbstschusse, 1967), Stephen Dwoskin (Chinese Checkers, Naissant, Soliloquy, 1965-1967) and Martin Scorsese (The Big Shave, 1967).

![[i]Wavelenght[/i] (Michael Snow, USA, 1967). Register for the competition. Source: Royal Belgian Film Archive. img articles knokke04](/cinemacomparativecinema/images/ccc02/img_articles_knokke04.jpg)

Out of the competition, split among five programmes each shown only once, EXPRMNTL 4 showed a further 70 films. This included works by film-makers both in and out of the competition, or by the members of the jury of the competition and the films that have come too late to be included in the programme, or that are not recent enough for the organisers to consider (but still relevant, according to Ledoux), there are also the works in the expanded cinema festival, in which everything leads to thinking that it is precisely their ‘expanded’ character that has kept them apart from the competition (Ledoux wanted all films to be screened in the same conditions): Le Corbeau et le renard (Marcel Broodthaers, 1967), whose projection required a prepared screen with various inscriptions; Hawaiian Lullaby (Wim van der Linden, 1967), in which a shirtless dancer prances through the stage in front of a screening of a sunset; The New Electric Cinema (Piet Verdonk, 1967), projected on an aluminium foil screen and accompanied by the sound made by a vacuum cleaner; and lastly, Speak (1962), by the English artist John Latham, whose projection opens with the performance Juliet & Romeo, in which a man and a woman painted in red and blue and covered in newspapers undress each other. Only two films in the competition were shown on double screens: Il mostro verde (Tonino De Bernardi and Paolo Menzio, 1967) and A dam rib bed (Stan VanDerBeek, 1967).

![Predesigns by Eventstructure Research Group and Sigma Projects for their project [i]Moviemovie[/i]. Source: Royal Belgian Film Archive. img articles knokke05](/cinemacomparativecinema/images/ccc02/img_articles_knokke05.jpg)

Besides these projects, the organisers invited the Eventstructure Research Group and Sigma Projects from The Netherlands (Jeffrey Shaw, Tjebbe Van Tijen and Theo Botschuijver) to show Moviemovie, a multimedia spectacle in which four projectors diffuse abstract and coloured images over a gigantic transparent inflatable structure that was shapeless and changing, embracing spectators wishing to immerse themselves inside it. Somewhere between expanded cinema performance, lightshow (a form that was in full development in the US, in parallel to the rise of psychedelic music) and an alluring sophisticated party, Moviemovie was the most spectacular reconfiguration of the classic cinematic set-up shown at Knokke. By including this work and all the others mentioned above, EXPRMNTL 4 played an essential role in spreading the practices of expanded cinema and of the lightshowin Europe.11

The film programming continued after the festival throughout February in Brussels, at the Cinémathèque and the Musée du Cinéma. Put together in five categories (award-winning films, films in the competition, films out of competition, films that arrived after the deadline, films rejected by the selection jury), this side of the programming process reveals a fascinating initiative that doesn’t just show or allow us to revisit all the criteria, but that, above all, allows the criteria to be relativised: according to the first view, the selection jury and the competition jury. This process was completed by two full days of debates on the ‘Study weekend about the Knokke Competition’, organised by the Palais des Beaux-Arts. By way of introduction to this programme, Ledoux made the following statement, which sounds rather precious within the context of his not very frequent public pronouncements: ‘In Knokke, at the recent experimental film competition, it’s trendy to call films “bad” or “boring”. As if these opinions had any meaning, when they’re applied to experimental film! […] It’s not very important whether films are “good”, or whether the experience “works”, as long as it shows something tapping into a bigger drive, and it is more considered. If we wanted to set up a parallel with scientific experimentation, we would happily say that here we’re very often dealing with a fundamental search, which is not necessarily found to be applied from one day to the next’.12

It’s important to value the unique opportunity these sessions represented altogether. In what was then a fragmented landscape, in which film-makers worked in relative isolation, ignoring research started by others, and in which the chances to see these films were so extremely rare, ‘Knokke-le-Zoute […] was still standing strong as the only international meeting point for avant-garde film-makers’.13 In 1967, there was no other event that, like EXPRMNTL, was exclusively dedicated to cinematic experimentation, and that provided such a wide international view of it. At Knokke, film-makers could find out what was being made in other places and the public could find out what’s being made everywhere. Ledoux’s first preoccupation was to showcase, provoke encounters and create links.14

EXPRMNTL effectively played this catalyst role. It’s at Knokke that Mekas met Kubelka, in 1963, and where Varda, in the edition in Brussels in 1958, met Brakhage. For some film-makers, the very existence of the festival was a firing range: ‘Knokke was like the start’, said Birgit Hein. ‘We were artists, we were painters. We didn’t know anything about film’.15 We know that EXPRMNTL 4 would give an essential push not just to the career of Birgit and Wilhelm Hein (who at the time were still students) but also to setting up the German independent film scene. ‘For us, Knokke was a tremendously important event. Particularly, because our first film was shown in the competition, but also because Knokke gave us a chance to break through our isolation. And of course Knokke was also supposed to be where you could appear in public for the first time within the right framework. There was a huge number of meetings and get-togethers, and everyone was extremely enthusiastic. Our aim was to create a film co-op with American film-makers. We didn’t manage to, but from then there was an international network, contacts, names. In large part XSCREEN’s foundation was due to Knokke; that’s where we began inviting international film-makers to Cologne’.16

A similar interest in setting up networks had inspired Ledoux to organise during EXPRMNTL 4 an international meeting of film co-ops, which were the structures of distribution for independent cinema that emerged everywhere after the creation of the Film-makers’ Co-op in New York in 1960. This need to join up, to make a cultural network, was felt everywhere. ‘In truth, no one knows anyone. Not even on a national level’.17 On 28 December 1967, representatives of several co-ops met up in Knokke to talk about the issue of distributing avant-garde films on an international scale, and of the possibility of creating a European co-op. Shirley Clarke and P. Adams Sitney (New York), Robert Nelson (California), Stephen Dwoskin (London), Kirby Siber (Zürich), Alfredo Leonardi and Gabriele Oriani (Naples), Andi Engel (Frankfurt), Werner Nekes (Hamburg), among others, took part in these debates. Some of these co-ops had just been set up, such as the one in Hamburg, established a month earlier; others were set up right there and then, in the heat of these discussions.18

But Ledoux’s visión would have been incomplete if the programme had been limited to film. The project was more ambitious: it was about making the links between avant-garde film and other arts explicit, and to point to its central role in the arrangement. ‘Ledoux believes film is the creative language that’s going to make everything explode’,19 Jean-Pierre Van Tieghem declared; he took part in organising non-film-related events.

By organizing a meeting between experimental film, visual arts, music and theory, EXPRMNTL opened up, both in words and in actions a space for reflection and exchange. Talks, exhibitions, concerts, conferences, theatrical performances and happenings were layered and woven into a complex network of ideas. Robert Breer showed his Floats, normal motor-animated sculptures in permanent motion. Edmond Couchot, French pioneer of interactive art, presented Semaphora III, ‘a cybernetic system capable of reacting to any kind of sound, whether noise, voice or music, and to visually interpret it via light and motion elements’.20 Michelangelo Pistoletto’s paintings on mirrors and other reflective media integrated the viewer into his device. Lastly, the Denise René Gallery showed a series of multimedia works by Vasarely, Demarco, Soto, Sobrino, Le Parc, Morellet and Yvaral. Movement, light, reflection, reproduction: conceptually, all the exhibitions at EXPRMNTL 4 could be related to film.

![From a letter by Jacques Ledoux, designs by Robert Breer representing his [i]Floats[/i], a series of moving structures exhibit during EXPRMNTL 4. Source: Royal Belgian Film Archive. img articles knokke06](/cinemacomparativecinema/images/ccc02/img_articles_knokke06.jpg)

![The Holy Trinity by Hugo Claus in his theater piece [i]Masscheroen[/i], premiered during EXPRMNTL 4. Center: Bob Cobbing. img articles knokke07](/cinemacomparativecinema/images/ccc02/img_articles_knokke07.jpg)

Mauricio Kagel directed several works interpreted by the Kölner Ensemble für Neue Musik, while the collective Mu sica Elettronica Viva21 gave an epic 4-hour-long improvisation at the Salle du Lustre, right beneath Magritte’s fresco Le Domaine Enchanté. Armand Gatti read his last work, La Naissance, dedicated to Latin American guerrillas. It was there that Hugo Claus created Masscheroen , a theatrical piece inspired by the medieval tale of Marieke van Niemegen , whose blaspheming character and whose appearance as the Trinity on stage with several nude actors (among them, the English poet Bob Cobbing) ended up in some legal complications. Lastly, there were panels. Five debates around the theme of ‘Art in Today’s Society’ were coordinated by the critic René Micha. Among the contributors figured artists such as Martial Raysse, Julio Le Parc, Yaacov Agam and Piotr Kowalski, writers such as Peter Handke, Maurice Roche, Claude Roy, Jean-Pierre Attal, Alfred Kern, Armand Gatti, Jérôme Savary, Edoardo Sanguineti and Claude Ollier, as well as composers like Frederik Rzewski, Michel Philippot, André Souris and Konrad Boehmer .

Another roundtable took place under the theme of ‘Art of experimentation and large public’, as well as a panel discussion around the use of the human voice as an instrument.

In this way, the programme of EXPRMNTL 4 spilled out of the screening room. Four of the casino spaces were used, so that Ledoux’s project unfolded across the whole building, in permanent motion, conceptually, artistically and spatially22. The constant movement is created by the festival visitors, who the press refers to as the ‘hippies’ invading the casino, frightening off the regulars. It is an audience that comes and goes during the screenings, that boos the films it disapproves of, that has appropriated the building. In this effervescent atmosphere, it’s not surprising that many projects were quickly added to the official programme. It’s the unexpected part of the festival, which Ledoux did not realise would gain such significant proportion23.

In purest underground tradition, some of the screenings happened outside the official programme. Everyone has heard about Flaming Creatures being banned and its subsequent clandestine screenings over the course of EXPRMNTL 3. No doubt the mythical aura that grew around these events played an important role in the expectations of visitors to EXPRMNTL 4. Some film-makers brought a film to show that it hasn’t been selected by the festival, others come with their latest work. In this way, and rather quickly, many parallel events are improvised inside, but above all outside, the casino (in a hotel room, in the room next door to a café). The French performer Jean-Jacques Lebel, who had been invited by the organisers of Knokke to be part of the talks, helped organise these events. Of these ‘illegal’ screenings, details of which are still mostly unknown (as they left no traces behind), we know at least a few:24 an 8mm pornographic poem by Henry Howard (member of the Living Theatre), Le Corbeau et le renard by Marcel Broodthaers , some reels by Pierre Clémenti, a film by Lebel. These events, which were very successful, entailed a questioning of the authority of the festival and of the very principle behind its selection.

In this increasingly challenging atmosphere, several unexpected interventions emerge in the casino itself: having arrived to accompany the out of competition screening of her Film Number Four (1967), Yoko Ono also performed her Black Bag Piece , for which she spent several hours under a cover of black canvas in the casino’s lobby. Arriving with various musician friends, Pierre Clémenti improvised with them all around the festival. Mouna Aguigui, an eccentric personality in the streets of Paris and Niza, came to Knokke to rally the crowd. Improv-style, Musica Elettronica Viva made an accompaniment for Moviemovie, but also for John Latham’s performance Juliet & Romeo . In a climate of uninterrupted exchange, spontaneous bonds were made between artists. It’s easy to agree with Maxa Zoller, who has described EXPRMNTL 4 as ‘a total expanded cinema experience’ and as ‘a festival of expanded art’.25

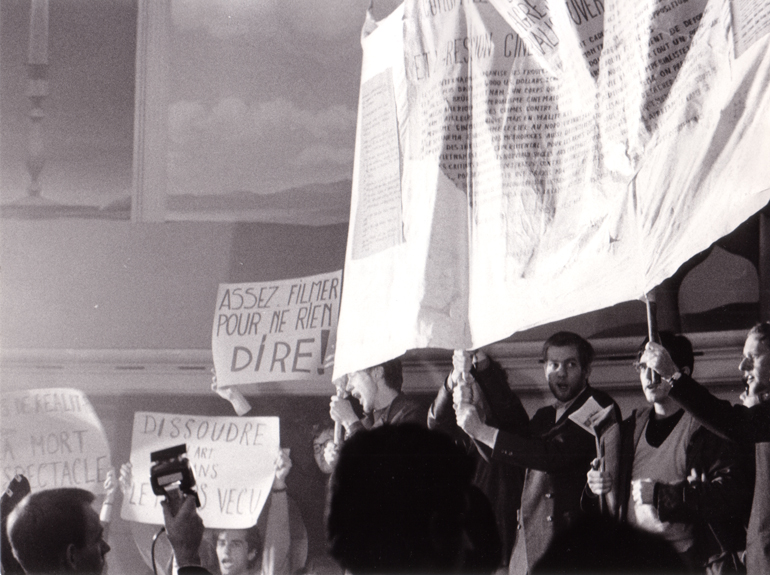

‘Everyone has complete freedom of expression’, Ledoux had announced. ‘This year the festival will continue this tradition.’26 In what starts to feel like a gigantic improvisation, other surprise guests arrived. A few months before May 1968, and in the heat of the protests already shaking up Germany at the height of the student movement, representatives for all leftist causes – maoists, marxists, anarchists, provos from Amsterdam27– converged at Knokke. Among them, a group of German students have made the journey. Coming primarily from two schools, the Deutschen Film- und Fernsehakademie in Berlin and the Institut für Filmgestaltung in Ulm, they were driven to Knokke by their passion for film. 28 However, the students were going to protest against the majority of the films shown at EXPRMNTL and against the festival itself by way of various spectacular actions. Situating itself against the lack of political commitment by most of the avant-garde film-makers, and particularly against the American participants, their protest was both about experimental cinema in its quasi-totality and the festival itself.

Harun Farocki, Holger Meins, Gerd Conradt (Berlin) and Oimel Mai (Ulm) form part of this group29. Conradt was the only one among them who was showing a film at Knokke, out of competition: Frederic Rzewski ißt spaghetti bei Carlone – Via della Luce 55 – Rom – Italien – 26 August 1967 (1966), filmed with the composer Frederic Rzweski , who is also at Knokke with the group Musica Elettronica Viva . Farocki had just produced the short film Die Worte des Vorsitzenden (1967), as a direct reaction against the death of a student knocked down by the police in the protests organised in Berlin against the Shah of Iran’s visit – an event which would mark the spread of the protest movement beyond the university context.

According to Farocki, Meins and Mai led the actions at Knokke30. The first one is still linked above all with the history of the Red Army Faction, but at the time of EXPRMNTL 4 Meins still obviously hadn’t chosen the path of terrorism. Other than Oskar Langenfeld (1966), the school documentary he made a year before and the only work he’s credited with directing, Meins had also collaborated in works by some of his classmates, specially as the camera in the Farocki film referred to above, Die Worte des Vorsitzenden . Most importantly, a year later he would also be credited with directing Herstellung eines Molotow-Cocktails (1968) , an agit-prop film of which there are no extant copies31, which details, through images, how to make a molotov cocktail. Oimel Mai, who studied with Alexander Kluge in Ulm, in 1969, would direct Elitetruppe Fleur de Marie , a political-fiction work described by Jean-Pierre Bouyxou in La science-fiction au cinéma as a ‘space opera with marxist-leninist pretensions’.32

If Farocki has commented on Meins’ (and his) enthusiasm for some of the films discovered by EXPRMNTL 4, such as Michael Snow’s Wavelength, 33 what really struck them was the political aphasia in most of the films they saw at Knokke. During this period of demonstrations against the Vietnam War, students let themselves get carried away by the feeling of an imminent revolution and by the reaction against the senselessness of their position as spectators, and decide to speak up: ‘We can’t stay sitting down at a film festival. We have to do something, here too’.34 Their intervention was recorded by several actions, some of which oddly recall expanded cinema performances.35 The first one was related to the screening of Wolfgang Ramsbott’s film Der weisse Hopfengarten (1966), during which, parading around in front of the screen like soldiers, the students took hold of the Christmas trees on the stage and point them at the audience, resembling a firing squad. The second one disrupted the screening of The Embryo (Koji Wakamatsu, 1966) in which, kidnapped and drugged, a shoeshop saleswoman endures awful torture by her boss. Roland Lethem had found The Embryo on a trip to Tokyo, and had advised Wakamatsu to submit his film to the competition at Knokke. ‘His film,’ Lethem would relate, ‘was a scandal, and leftist students in Berlin tried to stop the second screening by making a human pyramid in front of the screen. These students wanted to light the stage backdrop on fire. I can still see Wakamatsu, facing the spectacle of these hostile protestors, laughing his head off in a corner of the screening room.’36

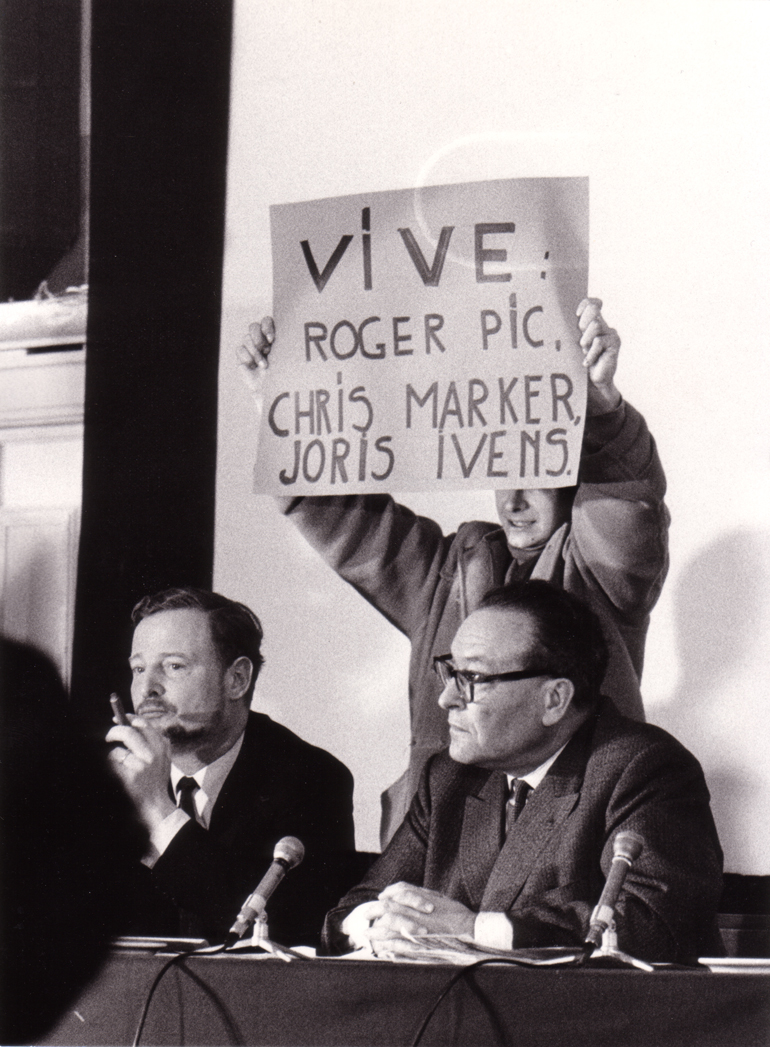

Leaving the screening, the German students, accompanied by some others from Belgium, began to put together a large manifesto-panel directed against American imperialism, in politics as well as in film. Besides this text, which would make a comparison between the military operations conducted by the US in Vietnam and the activity of experimental film-makers, stands this slogan: ‘The FLN is the only jury’. Exhibited for a few seconds in the casino hall, the manifesto would soon be destroyed by the casino’s director, who wanted to stop any political demonstrations within the context of his establishment. If the violence of his reaction would grant the students the solidarity of some spectators, others, like Shirley Clarke, did not take shortcuts with their reasonings: ‘You’re blaming the wrong Americans’,37 they’d point out to the students.

![Fotografía tomada por Ed van der Elsken durante la elección de [i]Miss Expérimentation[/i]. A la izquierda, Jacques Lebel y Harum Farocki. Sentados en la mesa están los miembros de la selección del jurado. Encima de la mesa, un candidato desnudo al título de [i]Miss Expérimentation[/i]. En la pared, un detalle del fresco de René Magritte [i]Le Domaine Enchanté[/i]. Publicada en [i]Skoop[/i], 1968. img articles knokke09](/cinemacomparativecinema/images/ccc02/img_articles_knokke09.jpg)

![[i]Miss Expérimentation[/i]. Jean-Jacques Lebel posando con dos candidatos. Fotografía publicada en [i]Skoop[/i], 1968. img articles knokke10](/cinemacomparativecinema/images/ccc02/img_articles_knokke10.jpg)

![[i]Miss Expérimentation[/i]. Jean-Jacques Lebel posando con dos candidatos. Fotografía publicada en [i]Skoop[/i], 1968. img articles knokke10b](/cinemacomparativecinema/images/ccc02/img_articles_knokke10b.jpg)

![[i]Miss Expérimentation[/i]: Jean-Jacques Lebel y Yoko Ono. Fotografía de Virginia Leirens. Fuente: Royal Belgian Film Archive. img articles knokke11](/cinemacomparativecinema/images/ccc02/img_articles_knokke11.jpg)

On 31 December 1967, the last day of the festival, the EXPRMNTL programme foresaw a debate about the films in the competition. Ledoux’s interesting initiative gave the audience the chance to ask the selection jury questions about the criteria that had guided their work, but above all to question the relevance of the very idea of a selection. Lebel quickly took the floor. After congratulating the organisers for their transdisciplinary approach, he announced the immediate selection of Miss Expérimentation 1967. On the stage, nude, two young men and women (one of them being Yoko Ono) put themselves forward for the contest. One of the young men was chosen. Taking advantage of the chaos, just as has been agreed with Lebel, demonstrators took the stage, waving a banner onto which the torn fragments of their sign have been glued, and brandished placards on which slogans such as ‘Long live Roger Pic, Chris Marker, Joris Ivens’, ‘Dissolve art in the living time’, ‘No reality without the death of spectacle’, ‘Silent cinema’ or even ‘Long live Dziga Vertov’ could be read. While the winner of the Miss Expérimentation contest swung his hips over the table of the selection jury, the demonstrators threw pamphlets towards the crowd, shouting ‘Reality!’ and ‘Awareness!’ It’s worth seeing images of this astounding scene, which breaks out immediately after in the hall – protestors, casino guards and police coming to blows. The show Moviemovie followed the fight, and later the traditional breughelesque Christmas Eve dinner. An unforgettable evening, the final bouquet for a rough week.

Temporary and of a pragmatic nature, the exclusive bond between the performative form of the radical militancy and the libertarian opposition had suddenly put in question the power of the organisers (exercised particularly through the selection of films), the links between the organisation and power and money (Pierre Vermeylen, president of the Cinémathèque, was a minister; the event was supported by private companies), and the films themselves. This critique had its relevance inasmuch as it highlighted the undeniable institutional regulations of the event, and the low number of explicitly political films at the heart of the programme. But in 1967, could political compromise in film not also happen within formal experimentation? Could it not be the vehicle for a new radical questioning of values, whose reach was also political? Recontextualizing the disagreement that in Germany, and also in other places, set up an opposition between experimental and political film-makers, Birgit Hein recalls: ‘political film-makers totally ignored the relevance of a formally innovative art. At that time we were considered reactionary avant-garde film-makers, which really annoyed us. In the contrary, we felt that some political films, with their clear claims, were reactionary, because they were working with the same signs as traditional commercial cinema. Back then, these two contexts were truly separate’.38 And nevertheless: ‘It wasn’t easy because of course we were all on the same side’.39

Opposed to the repressive attitude of the casino director and of the president of the Cinémathèque regarding problems encountered at the festival, Ledoux’s seemed conciliatory. Although he would remain in his role, the curator of the film archive seemed to have understood that those out of control skids formed an integral part of the event. ‘Far from seeing an attempt to sabotaje his work in outbursts of all kinds […], he considered them to be the extension of it, even if their nature sometimes left him perplexed’.40 One would think that at the core of EXPRMNTL, Ledoux, despite his reputation, was working to replace it with an open structure, conscious that otherwise it could get away from him. In this locked up space, like in a lab, his attitude as programmer consisted of setting up the conditions and the actors for the experience, and to precipitate the encounter, embracing the idea of allowing himself to be surprised as the events unfolded.

Spilling out of the conventional limits of a film festival, EXPRMNTL 4 was a multipurpose affair. The encounter, the opening, all the way to the outburst, were at the heart of its project. EXPRMNTL worked to reinvent the very notion of the festival, underscoring the specificity of this very particular presentation context: the festival, neither a museum, nor gallery, nor film theatre, was the construction of a temporary and collective situation, an experience of itself. Ledoux provided the framework for a phenomenon of which he did not know the limits, and the happening came to answer itself. ‘There were several sideshow attractions,’ Werner Nekes said, ‘and the political happening was also like a kind of attraction’.41

A few months later, Harun Farocki, Holger Meins, Hartmut Bitomsky, Wolfgang Petersen and about ten more students were kicked out of the Deutschen Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlín for their political activities.42 Meins went on to join the Red Army Faction in 1970. Arrested two years later, he died in jail in November 1974, following a hunger strike. Besides the two portraits dedicated to him by his old classmate Gerd Conradt, at least two films were dedicated to his memory: La Tête d'un frère (Roland Lethem, 1974, screened outside the competition at EXPRMNTL 5) and Moses und Aron (Jean-Marie Straub, Danièle Huillet, 1974).

Soon after the festival, Shirley Clarke was interviewed in Paris by Noël Burch and André S. Labarthe, in one of the most relaxed portraits in the Cinéastes, de notre temps43 series. Jean-Jacques Lebel and Yoko Ono were also in the room, providing a feeling of being at the EXPRMNTL 4 afterparty for the viewer. Clarke evokes the urgency of those new cinematic approximations, which for her have everything to do with the profound crisis affecting society at all levels at that time: ‘I think Rome is burning. Which is always a good time to let oneself go. […] A new world is coming. The end of this world is coming, but a new world will take its place’.

Six months after EXPRMNTL 4, with May 1968 in full swing (Jean-Jacques Lebel will be a feverish participant), the Cannes film festival was called off under the influence of nouvelle vague film-makers, including Jean-Luc Godard, who as it happens also interrupted a film festival a few months after Harun Farocki. No Palm D’Ors were awarded that year.

EXPRMNTL held one more edition, its last, seven years later, in 1974.

Translated by Lupe Núñez-Fernández.

FOOTNOTES

1 / FAROCKI, Harun (2009). ‘Written Trailers’, in Harun Farocki. Against What? Against Whom?. London, Koenig Books/ Raven Row, p. 222. Farocki also recalls the events at Knokke in an article included in Trafic magazine (‘Une extrême passion’, in Trafic, n. 30, summer, 1999, pp. 17-20) and in the second of two films that Gerd Conradt, his former classmate at the Berlin Academy, dedicated to Holger Meins (Starbuck - Holger Meins, 2001).

2 / ‘Comité Consultatif X5. Réunion du 11 février 1974’: Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique, X5. Programmed non-cinema protests, under the name Rapport Comité Consultatif. This programme also serves as proof; it was put together after the tumultuous editions of the festival in 1963 and 1967.

3 / «Everything that Ledoux has ever set out to do has always been Ledoux’ business from the beginning in fine» (Gabrielle Claes, interview with the author, 26 abril, 1999); «Jacques Ledoux was very possessive, a tiranical and dominant person, who wanted to do and control everything» (Dimitri Balachoff, quoted by HEAD, Anne, A true love for cinema. Jacques Ledoux, 1921-1988, Rotterdam, Universitaire Pers, 1988, p. 16).

4 / BUCHET, Jean-Marie,«Ledoux exprmntl film», Revue belge du cinéma, n° 40, November, 1995, p. 34.

5 / The selection jury, which was always fully Belgian, in 1963 included Dimitri Balachoff, Yannick Bruynoghe, Paul Davay, André Vandenbunder and Roland Verhavert.

6 / A member of the Belgian Socialist Party, Vermeylen was a senator from 1945 to 1974, Home Office Minister from 1947 to 1949 and from 1954 to 1958, Justice Minister from 1961 to 1964 and Education Minister from 1968 to 1972.

7 / EXPRMNTL 4. Fourth International Experimental Film Competition organized by the Royal Belgian Archive of Belgium. Casino Knokke / 25.XII.1967-2.I.1968, Royal Filmarchive of Belgium, published with assistance from the Belgian Commission for UNESCO, 1967, unpaginated.

8 / Unsere Afrikareise (1966) by Peter Kubelka for example, was excluded from the competition because it had already been shown a few times in Europe, particularly by Ledoux at the Musée du Cinéma. «The possibility of discovering new talent had never before been so explicit, or had been pushed so far», P. Adams Sitney remarked. SITNEY, P. Adams, ‘Report on the Fourth International Experimental Film Exposition at Knokke-le-Zoute’, in Film Culture, n. 46, Autumn, 1967, published –belatedly– in October 1968, p. 7.

9 / According to Danielle Nicolas, who later on became Ledoux’s assistant (HEAD, Anne, op. cit., pp. 54-55).

10 / Pontus Hulten would be announced as the fifth member of the jury. Due to illness he was unable to attend.

11 / ‘Interview. Gabriele Jutz with Birgit Hein’, in MICHALKA, Matthias (ed.), X-Screen. Film Installations and Actions in the 1960s and 1970s, Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien / Walther König, Vienna / Cologne, 2004, p.125.

12 / February 1968 programme at the Musée du Cinéma, Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique.

13 / SITNEY, P. Adams, Op. Cit., p. 6.

14 / This is why, for example, the festival catalogue includes contributions from all the film-makers. «We did this to encourage engagement between film-makers, their work and between the film-makers and their public. To us this seemed to be more necessary in the context of experimental film, where there is a large risk of misunderstandings and incomprehension. We hope to gain and provoke those kinds of exchanges on every level, whether it be economic, aesthetic or critical» (EXPRMNTL 4, op. cit).

15 / Birgit Hein, interview with the author, Berlin, 26 August 2012.

16 / MICHALKA, Matthias, Op. Cit., pp. 118-119.

17 / Birgit Hein, interview with the author, Berlin, 26 August 2012.

18 / A second gathering followed this meeting at Knokke, in Munich, November 1968, organised by the Heins and Klaus Schönherr.

19 / Jean-Pierre Van Tieghem, interview with the author, 11 January 1999.

20 / Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique, Exprmntl 4/drukwerken/imprimés, 25.

21 / Allan Bryant, Alvin Curran, Jon Phetteplace, Carol Plantamura, Frederic Rzewski, Richard Teitelbaum and Ivan Vandor.

22 / Without taking into consideration the spaces taken up by off-festival events, something that will be discussed later on.

23 / YALKUT, Jud «Freaking the Festival Factions. Report from the Belgium Film Festival», in New York Free Press, 8th February 1968, p. 14.

24 / SITNEY, P. Adams, Op. Cit., p. 9; YALKUT, Jud, Op. Cit., p. 9.

25 / ZOLLER, Maximiliane, Places of Projection. Re-contextualizing the European Experimental Film Canon, doctoral thesis, Birbeck College London, School of History of Art, Film and Visual Media. Tutor: Profesor Ian Christie, 2007, pp. 129 and 124.

26 / MAELSTAF, Raoul, «Knokke 1967-8», interview with Jacques Ledoux, Cinema TV Digest, n° 18 (vol. 5, n° 2), Autumn, 1967, p. 3.

27 / MICHA, René, «Cinéma expérimental», La Nouvelle Revue Française, n° 184, April, 1968, p. 717; BOUQUET, Stéphane, BURDEAU, Emmanuel, «Rhizome universel. Entretien avec Jean-Jacques Lebel», in Cahiers du Cinéma, special edition: Cinéma 68, 1998, p. 65 ; Jean-Marie Buchet, interview with the author, Brussels, 12 November 1998.

28 / Some of them were connected to the Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund (SDS), the federation of German socialist students.

29 / Two other film students, Hartmut Bitomsky (Berlin) and Jeanine Meerapfel (Ulm) were also present at Knokke, but it appears they did not take part in the demonstrations. FAROCKI, Harun, interview with the author, Brussels, 20 April 2013.

30 / Starbuck - Holger Meins (Gerd Conradt, 2001).

31 / A reconstruction of the film can be seen in Gerd Conradt’s film Starbuck – Holger Meins (2001).

32 / BOUYXOU, Jean-Pierre, La science-fiction au cinéma, Union Générale d’Edition, Paris, 1971, p. 116.

33 / BAUMGÄRTEL, Tilman «Der kleine Ausschlag für eine große Entscheidung Interview mit Harun Farocki über den deutschen Herbst», www.libertad.de/inhalt/spezial/holger/jw41harunfarocki.shtml, undated, last accessed: 16 March 2013.

34 / Harun Farocki commenting retrospectively on the events at Knokke in Gerd Conradt’s film Starbuck - Holger Meins (2001).

35 / The footage taken at the festival by Claudia Aleman and Reinold E. Thiel for the Westdeutscher Rundfunk document the events well ( Experimental 4 – Knokke. Vierter Wettbewerb des experimentellen Films , broadcast programme, WDR, Cologne, 1968). Aleman and Thiel seem to share implicitly the point of view of the students – something not very surprising considering that Claudia Aleman was at the time also studying at the Ulm school. Thiel will later on in 1969 produce Harun Farocki’s film Nicht Löschbares Feuer (on which Gerd Conradt was cameraman).

36 / LETHEM, Roland, ‘Koji Wakamatsu à Knokke, Noël-Nouvel An 1967-68’, published in Japanese in the journal Bun Gei , special Wakamatsu edition ( Ko ji Wakamatsu, the genius who kept fighting), January 2013, Kawade, Tokyo, p. 135. Original text in French given to the author by Roland Lethem. Ironically, the protestors’ action interrupted a film by a film-maker very renowned for his commitment (at least in Japan), to the point that in his home country students refer to him as ‘Che’.

37 / YALKUT, Jud, Op. Cit., p. 14.

38 / « Interview. Gabriele Jutz with Birgit Hein», p. 121.

39 / Birgit Hein, interview. Regarding Harun Farocki and EXPRMNTL 4: «Retrospectively, it was the last time when politics and the avant-garde, aesthetics and politics, still held equal presence. From then on they became separate. In 1968 they started to grow apart in full force. […] Different factions started to emerge. Up to then it had been a single force – with many different elements, but that were all happening together». FAROCKI, Harun, op. cit.

40 / BUCHET, Jean-Marie, Op. Cit., p. 33.

41 / Werner Nekes, interview with the author, Brussels, 11 July 1998.

42 / FAROCKI, Harun, Op. Cit., p. 222.

43 / Rome is Burning (Portrait of Shirley Clarke) (Noël Burch and André S. Labarthe, 1970).

ABSTRACT

This article compiles the several manifestations and witness’ accounts of the 4th edition of the International Festival of International Cinema of Knokke-le-Zoute (EXPRMNTL 4), celebrated in 1967: its conception by Jacques Ledoux and the Cinémathèque Royale de Bélgique and the evolution of the festival through its first editions, the aesthetic, political and cultural concerns, the competition programme and the non-filmic activities, as well as other events, such as the multimedia spectacle Moviemovie, the meetings to stimulate the creation of an international network of American, European and Asian experimental film-makers or the concerts and performances, which extended well beyond the spaces of the Casino where the festival was held. Finally, the essay details some of the events that happened within the atmosphere of protest that marked that edition of 1967: from clandestine screenings to several demonstrations and forms of boycott, signalling the moment at which aesthetic and political avant-gardes began to diverge. Among the witnesses here compiled, it is worth mentioning the accounts of the film-makers Birgit and Wilhelm Hein and Harun Farocki.

KEYWORDS

EXPRMNTL, Knokke-le-Zoute, Jacques Ledoux, Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique, film programming, politics, experimental film, expanded cinema, Harun Farocki.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A.A.V.V. (1967), EXPRMNTL 4. Fourth International Experimental Film Competition organized by the Royal Belgian Archive of Belgium. Casino Knokke / 25.XII.1967-2.I.1968, Royal Filmarchive of Belgium, published with assistance from the Belgian Commission for UNESCO, 1967, unpaginated.

BAUMGÄRTEL, Tilman «Der kleine Ausschlag für eine große Entscheidung Interview mit Harun Farocki über den deutschen Herbst», www.libertad.de/inhalt/spezial/holger/jw41harunfarocki.shtml, undated, last accessed: 16 March 2013.

BOUQUET, Stéphane, BURDEAU, Emmanuel, «Rhizome universel. Entretien avec Jean-Jacques Lebel», in Cahiers du Cinéma, special edition: Cinéma 68, 1998, p. 65.

BOUYXOU, Jean-Pierre, La science-fiction au cinéma, Union Générale d’Edition, Paris, 1971, p. 116.

BUCHET, Jean-Marie (1995). «Ledoux exprmntl film», Revue belge du cinéma, n. 40, November, p. 34.

FAROCKI, Harun (1999) «Une extrême passion», Trafic, n. 30, Summer, pp. 17-20.

FAROCKI, Harun (2009). ‘Written Trailers’, in Harun Farocki. Against What? Against Whom? London, Koenig Books/ Raven Row, p. 222.

HEAD, Anne (1988). A true love for cinema. Jacques Ledoux, 1921-1988 Rotterdam, Universitaire Pers, p. 16.

LETHEM, Roland (2013). ‘Koji Wakamatsu à Knokke, Noël-Nouvel An 1967-68, Bun Gei’, special Wakamatsu edition (Koji Wakamatsu, the genius who kept fighting), January, p. 135.

MAELSTAF, Raoul, ‘Knokke 1967-8’, interview with Jacques Ledoux, Cinema TV Digest, n. 18 (vol. 5, n. 2), Autumn, 1967, p. 3.

MICHA, René, ‘Cinéma expérimental’, La Nouvelle Revue Française, n. 184, April, 1968, p. 717.

MICHALKA, Matthias (ed.) (2004). ‘Interview. Gabriele Jutz with Birgit Hein’, MICHALKA, Matthias (ed.) X-Screen. Film Installations and Actions in the 1960s and 1970s, Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien / Walther König, Vienna / Cologne, 2004, pp. 118-119, 125.

SITNEY, P. Adams (1967). ‘Report on the Fourth International Experimental Film Exposition at Knokke-le-Zoute’, Film Culture, n. 46, Autumn, p. 7.

YALKUT, Jud ‘Freaking the Festival Factions. Report from the Belgium Film Festival’, in New York Free Press, 8 February 1968, p. 14.

ZOLLER, Maximiliane, Places of Projection. Re-contextualizing the European Experimental Film Canon, doctoral thesis, Birbeck College London, School of History of Art, Film and Visual Media. Tutor: Professor Ian Christie, 2007, pp. 129 and 124.

XAVIER GARCIA BARDON

Xavier García Bardon is a film curator at the Centre For Fine Arts / Bozar Cinema and lectures at the Ecole de Recherche Graphique (both in Brussels). He completed his doctorate at the Université Paris-3 Sorbonne Nouvelle, under Nicole Brenez’s supervision, and has conducted extensive research on the history of the EXPRMNTL film festival at Knokke-le-Zoute (1949-1974), to which he has also devoted several film programmes and publications.

Nº 2 FORMS IN REVOLUTION

Editorial

Gonzalo de Lucas

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

The Power of Political, Militant, 'Leftist' Cinema. Interview with Jacques Rancière

Javier Bassas Vila

A conversation with Jackie Raynal

Pierre Léon (in collaboration with Fernando Ganzo)

Interview with Ken and Flo Jacobs. Part 1: Interruptions

David Phelps

ARTICLES

EXPRMNTL: an Expnded Festival. Programming and Polemics at EXPRMNTL 4, Knokke-le-Zoute, 1967

Xavier Garcia Bardon

The Wondrous 60s: an e-mail exchange between Miguel Marías and Peter von Bagh

Miguel Marías and Peter von Bagh

Paradoxes of the Nouvelle Vague

Marcos Uzal

REVIEWS

Glòria Salvadó Corretger: Spectres of Contemporary Portuguese Cinema: History and Ghost in the Images

Miguel Armas

Rithy Panh (in collaboration with Christophe Bataille): La eliminación

Alfonso Crespo