THE FILMIC SPACE ACCORDING TO FARBER1

Patrice Rollet

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

Manny Farber claims for a strictly ‘topographical’ writing despite, according to himself, this term overly entails the sign of unity of a filmic space that Godard’s collages of 1960’s have definitively turned problematic. He articulates his new configurations even in the titles themselves (Birthplace: Douglas, Ariz, 1979, Taking Off Grom A Road Picture, 1980; Across the Tracks, 1982, Earth, Fire, Air, Water, 1984, Change of Direction, 1985), as well as in the way in which he has forever, practiced the critic. His language attests, simultaneously, a stratigraphical and atmospheric attention towards the natural and urban landscapes that surrounded his life. From the very unusual inclination of the tablelands in San Diego, to the dimness of The Lyric, the movie theatre across his place in Douglas, without forgetting the dark crowds of those, where as an adolescent, he went to watch the action films by Hawks or Wellman […] but above all, the films approached as landscapes whose surface must be measured, literarily and in all directions, in order to discover inside them, unknown points of view, even fugitive, even improbable, even erratic, that will open upon them new critical perspectives. It is not so much about making visible the unsuspected details of a blurred cinematographic space, as to unveil the breaking points or the fracture lines that shake, in a subterranean fashion, the tectonic plates of a Californian falsely soothed landscape, and the films that Hollywood produces there. And the changing topography of Farber’s articles reveals itself, ultimately, as the fundamental landscape that should sum up all the rest within itself, through a scenography that changes on every occasion and that pushed to the limit, makes the most material architectural structure (the little typographic block that constituted, for example, the 800 words of his column and a half, in the space of The New Republic’s page, at the beginning of his career) dispute the critical dramaturgy.

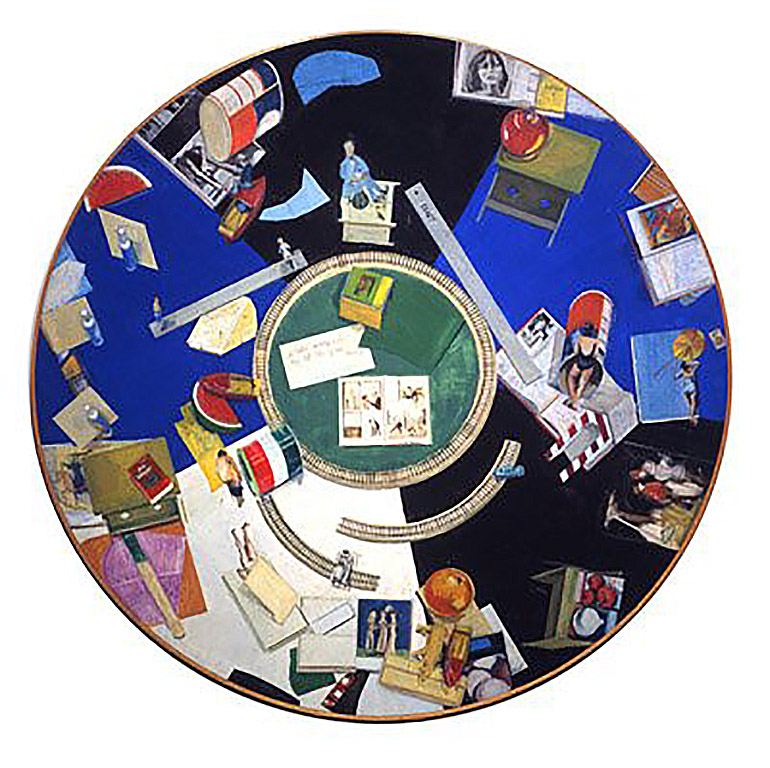

Then, cinema: art of space? Yes. But undoubtedly, more exactly in the sense that Eric Rohmer understood it in one of his first texts in La Revue du cinema, in which it already corresponded to the whole of the filmic space, rather than to the interior of each shot, to respond to certain conception of cinematic spatiality (narrowness of its visual surface and breadth of its place of action). Faber, kindly goes off on a tangent in Rohmer’s Knee, a circular painting of 1982,through the figure of two grey metallic rulers that give dynamism to the central railroads. Simultaneously he pushes some of the fiction corpuscles removed from the work of the filmmaker (Clara’s knee, or Chloè’s face in Chloè in the Afternoon (L’Amour l’après-midi, Eric Rohmer, 1972) to the perimeter.

In the matter of fact, it would be instructive to compare until its parodic pedagogical dimension, or its common sense of retroactive envelope, term by term, the three spaces that Rohmer would latter identify to shed lights on the formal setup of Faust (1926) by F.W Murnau:

- ‘The pictorial space’ (The cinematographic image projected on the screen as representation of certain part of the physical world.)

- ‘The architectonical space’ (Those same parts of the natural or artificial world in relation to which the filmmaker measures himself during the shooting.)

- ‘The filmic space’, in the strict sense, (a virtual space suggested to the spectator with the help of the two precedent elements, rather than the filmed space itself.)

With the three spaces formulated by Farber in the introduction of his book, with the particularly precious concern whilst exceptional to him, for an almost conceptual clarification of his thought:

- ‘The field of the screen’ (that approximately corresponds to the pictorial space of Rohmer.)

-

‘The psychological space of the actor’ (that Rohmer does not mention in the opening of his thesis statement, but to which he later returns, and that for Farber, does not belong exclusively to the mental or imaginary order, given that the performance of the actor can progressively dig or fill, empty or overflow, make precise, or instead undetermined, very directly, very concretely, very physically, the filmic space that he brings into existence or makes disappears, in the same terms that the framing, the light or the montage: They are Rita Tuwhinghan, Jeanne Moreau and above all, Giuleitta Masina,‘three tiny women –swell their proportions to gigantism with gestures and decor’ (FARBER, 2009: 559), placed by the side of Ida Lupino who ‘has her place, and, retracting into herself, steals scenes from Bogart at his most touching’ (FARBER, 2009 :691) in High Sierra (Raoul Walsh, 1941), of Liv Ullmann,‘one of those rare passive Elegants in acting who can leave the screen to another actor and still score’ (FARBER, 2009: 610), in Hour of the Wolf (Vargtimmen, Ingmar Bergman, 1968) or of Lynn Carlin, whose‘role out sight by the time her husband returns from a bored-with-job whore’ (FARBER, 2009: 637) in Faces (John Cassavetes, 1968).

Nobody has been able to elucidate this space of interpretation as Farber, with all the nuances that the acidity of an etching may authorize: in the golden age of its history the American actor, but not him exclusively, testifies moments of grace and absolute coherence in his interpretation, always keeping himself, even at those moments, in the periphery of his role and like adjacent to his own self; not as Marlo Brando or Paul Newman, watching themselves act for pleasure, but as Burt Lancaster, seeming to‘disappear into concentration’ (FARBER, 2009: 588), Sean Connery, ‘sifting into a scene, covertly inflicting a soft dramatic quality inside the external toughness’ (FARBER, 2009: 560), or Henry Fonda, creating the impression of ‘walking backward, slanting himself away from the public eye’ (FARBER, 2009: 577). Therefore, the main roles have the supreme class and elegance, in my concept, of a Gary Cooper that will later remind a Harrison Ford, characterized by always having an apologizing look for being in the shot; while secondary roles, as Leonid Kinsky in Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942), Eugene Pallette and Eric Blore in a film by Preston Sturges, mobilize an ‘whirring energy is created in back of the static mannered acting of some Great Star’ (FARBER, 2009: 559). In his decline and in ‘cartooned hip acting’ (FARBER, 2009: 588), the actor only shows an intermittent sample of what he can do […] He can no longer afford the slightest deviation from a movie that, henceforth considers itself to be an equal to a painting or a symphony, completely controlled by their author.

Bottom: Faces (John Cassavetes, 1968)

-

‘The area of experience and geography that the film covers’ (that as the filmic space in Rohmer, contains the other two, but implies less the peaceful virtuality of an ideally reconstructed space by the spectator’s mind, than precisely a more uncomfortable negativity –and this is the whole difference– of a space without boundaries, like those images expanding over a page without being delimited by any margins. This space serves as a reverberation pedal, or as a sound box of the film beyond itself. It gradually connects the apparently most distant territories of an experience lived in a state of perception, well seen by Rohmer, between perception and conscience.But, in the case of Farber in an area of the cinematographic unconscious even more difficult to localize, which belongs equally to the spectator and the filmmaker, and leads in the intersection of its paths, to both the hidden interiors of the literally unsolvable space of the structural cinema, and the great highway of the American road movies of the 1970’s, always opened to the exterior.

This work around the negative, that in any case has to be reduced to a philosophical figure (though the termite has some reminiscences to the old mole of some), reminds us that to Farber’s eyes, though he feels disgusted for the development of a general theory, the filmic space too, has a history, in which the organic richness of works by Hawks, Walsh, or Wellman irrevocably gave over its place to the more singular excavations of Antonioni, Pasolini or Godard; Just to mention two critical moments of a more complex adventure where different sceneries succeeded each other, without exclusiveness or long term existence, in some cases.

The great era of the burlesque could embody the paragon of a primary space, not to say primitive, that would oscillate –Keaton in the middle point of a distant command, somehow detached from the frame that surrounds his own self – between the two antithetical positions of Chaplin, who adapts the frame to himself and controls the space that surrounds him from within the shot (even when everything moves around him and he is trapped, despite the resistance of his own body, in the apparently irreversible movement of the assembly line in Modern Times 1936) and of Laurel and Hardy in their short films, where they accept, to really lose themselves in the frame, moreover pursuing their efforts, trough the centrifugal force of their gestures and their actions that reach insanity, to plunder and disperse the slightest decor, until they get to completely dissolve, both in literal an figurative sense, the space that surrounds them. (Whatever it is, all-over, but political and social as well. The environment of American suburbs with its slight desire for money, for material comfort and for public recognition, is subjected from the outset, to the constant confrontation with the police, the wasteful expenses, and the return to the formless in some terrains more than desolated: for example, the destructive Big Business 1929 by James Horne y Leo McCarey, that presents –with the occasion of the door-to-door selling, as derisory as incongruous, at Jimmy Finlayson’s residence, where Lauren and Hardy arrive to sell him a Christmas tree in the middle of summer, after they respond to the unfortunate crack that sectioned a part of their conifer, with a minuscule slash to the frame door– a progressive but irreversible rise and the reach of the climax, contrasted with slow burnings and calculated answers, that lead to the final paroxysm of the movie, cataclysmic until the point where, it transforms one’s bay window, the other’s car and all the intermediate space of the street and the garden that was keeping them apart just a few seconds ago, into moon craters).

Let us change the time and the genre now. If Manny Farber and Patricia Patterson, with the risk of disturbing the conveniences –are they by any chance seriously mistaken?– prefer The Far Country (Anthony Mann, 1954) rather than The Searchers (John Ford, 1956), is mostly, and despite certain internal contractions, not to say contradictions, of the internal space it implies (particularly, the claustrophobic impression of The Searchers, antithetic to the ideaof the screenplay by Borden Chase, aroused by the staging of a meagre porch, too narrow to be contiguous to any lounge, or of a ship cabin, too small to hide oneself in it) a result of the ability of Mann’s western to make the landscape exist beyond the frame where yet the artifice and transparency of the studio decor reigns, just by placing its characters in general, and James Stewart in particular, off-centre. There, where Ford’s movie, centring the vignettes of its shots on a John Wane reduced to a stamp figure, returns, through that gesture which borders mannerism, to the natural and savage beauty of the Monument Valley tablelands the status of a jewellery case, sublime but somehow vain, of the actions that take place there. To Wayne’s almost heavy loneliness responds the more subtle misanthropy of Stewart, that rejects him to the border of the frame as much as society does, being always on the periphery, of one and the other. And nothing annoys the artist and the critic more than those ‘framing’ effects, in all the senses of the word, that limits the infinite enlargement of the painted, filmed, written space, beyond itself.

More than the apparent disenchantment, the dispossession, the nausea that immerses their protagonists, or the slowing down of their actions until the stagnation of an unbearable face to face with the spectator, what characterizes modernity and, as Farber also writes ‘the whole riverbed of films shifted’ (FARBER, 2009: 622)under the calmed and impassive pressure of the first works by Antonioni in the 1960’s, is exactly the abandonment of the organic, of the continuity and complexity of space, for the sake of a new primitivism that results in a simplification of the form, a confrontation of the tones, a fragmentation of the screen, and even in a montage-collage. In modernists terms, it is also about the rise of the surface in relation to the depth (the flat backgrounds of the blue sky in Contempt [Le Mépris, Jean-Luc Godard, 1963]), the all-over setup of that surface (even the erotic treatment of the body of Faye Dunaway the way she walks in Bonnie and Clyde [Arthur Penn, 1967]), the transit from figuration to abstraction of an stylized composition (the formal pureness revealed by the faces, the profiles and the napes in Persona [Ingmar Bergman, 1966]), or the vertigo in the representation that originates the mise-en-abyme of the images (the gestural and verbal repetition and amplification of the Dean Martin’s interpretation with the one of the husband, in Some Came Running [Vincent Minnelli, 1958]). Radicalized, all these procedures culminate in the irreducibly opened works of the underground cinema by Shirley Clarke, Peter Emanuel Goldman or an early Cassavetes, with their completely dull characters, the raw brutality of their cinematography, and the limitless of time suggested by the undetermined stream of an endless present.

The cinema of the 1970’s, both American and European, failing to recognize the modern divorce between surface and depth, redeploy the elements of both components, according to Farber, with no emphasis or principles requirements (unlike the declared ruptures of Citizen Kane [Orson Welles, 1941] or The adventure [L’avventura, Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960]), trough the confrontation, that eventually was imposed, of a ‘dispersal space’ (FARBER, 2009: 762),that does not lack depth,(Mean Streets [Martin Scorsese, 1973], McCabe and Mrs. Miller [Robert Altman, 1971], Céline and Julie go boating [Céline et Julie vont en bateau, Jacques Rivette, 1974]), and a ‘shallow-boxed’ (FARBER, 2009: 762), that goes out of its area ([Katzelmacher Reiner Werner Fassbinder, 1969], In the realm of the senses [Ai no korîda, Nagisa Oshima, 1976], Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles [Chantal Akerman, 1975]). The fluctuant, discontinuous, atomized world of one, is corresponded to the geometrical clarity, the frontal filming and the structural isomorphism of the part and the whole, of the other. But what both have in common, besides the pleasure for triviality and the denial for a closure (the density and the enigma of the world seem to merge in the termite cinema of that time), is a literal way to confront things, very distant to the dominant allegories of the 1960’s. Thus, a more beautiful part is reserved for the ellipsis, the lapses and the transitions to the void (if not transitions to the act), that can not completely fulfil the obsessive rituals of Jeanne Deilman, but instead liberate the happiest imaginary games of Céline and Julie, whose willingly vagueness is comparable to «Cézanne watercolour, where more than half the event is elided to allow energy to move in and out of vague landscape notations» (FARBER, 2009: 763).

Negative space, once again, which can be verified through the history of its forms, always in motion; Not in the sense of an amplified shadow of the works but in an enunciable negative greatness or the antimatter which constantly enlarges the film universe, or even in the sense of those black holes which no longer emit any light because of the density of their own mass, but whose hypothesis has to be admitted in order to shed lights on its very real effects on the gravitational field of the bodies. That is to say, that the negative space is not reduced to the common places of the reverse field or the space off-screen of the academic studies, which would only be one category of all this, upon many possible, and not the most stirring one. These studies involve the whole regions of experience, which can never become absolute: opened, rather than encompassed by the films, beyond and before themselves, in the bosom of all those artistic, geographic and political wider territories, to which they join as they can; usually in a subterranean way, often in the borders, in the very limit of the critical wilderness, once again in the periphery of a cinematographic civilization where nor the cartoon by Chuck Jones, nor the actions movies by Walsh, Fuller or Siegiel –not more than the unpretentious interpretations of Cagney or Wayne–, are taken seriously by the enlightened amateur, who only knew to think about the adaptation of the borderline beauty of the works eager to capture‘the unworked-over immediacy of life before it has been cooled by Art’ (FARBER, 2009: 424).Naturally, for Farber is about the scrabbled space from the gallery of termites, that as good as a carpenter he is, he well knows with a unique way of loving his most intimate enemy. The accepted myopia of the critic, his blind work, protects him from the very frequent mirages of sight and from the generalizations it implies, developing his other senses at the same time (‘the photographic ear’ (FARBER, 1998: 358) of Patricia, the pictorial touch of Manny, the taste of both for the chewed reflexion, their allergy to the inebriating scents of fashion). They take their chances for the vision that extol too high from the white elephant essayist, often praised with the halo of Great Art, occasionally sheltered under the reins of the Great Writer, but always prisoner, like Gulliver and Lilliput, of the thousand nets of the Holy Trinity of evaluation, interpretation and prescription.

ENDNOTES

1 / This article is an excerpt from the postface by Patrice Rollet published on the French edition of Manny Farber’s writings: Farber, Manny (2002). Espace Négatif. Paris. P.O.L. Deep thanks to Patrice Rollet for permission to reproduce this article.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

FARBER, Manny (1998). Negative Space. Manny Farber on the Movies. Expanded Edition. New York. Da Capo Press.

FARBER, Manny (2009). Farber on Film. The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber. POLITO, Robert (Ed.). New York. The Library of America.

Nº 4 MANNY FARBER: SYSTEMS OF MOVEMENT

Editorial

Gonzalo de Lucas

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEW

The Law of the Frame

Jean-Pierre Gorin & Kent Jones

DOCUMENTS. 4 ARTICLES BY FARBER

The Gimp

Manny Farber

Ozu's Films

Manny Farber

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Manny Farber & Patricia Patterson

Nearer My Agee to Thee (1965)

Manny Farber

DOCUMENTS. INTRODUCTIONS TO MANNY FARBER

Introduction to 'White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art and Other Writings on Film'

José Luis Guarner

Termite Makes Right. The Subterranean Criticism of Manny Farber

Jim Hoberman

Preface to 'Negative Space'

Robert Walsh

Other Roads, Other Tracks

Robert Polito

The Filmic Space According to Farber

Patrice Rollet

ARTICLES

Hybrid: Our Lives Together

Robert Walsh

The Dramaturgy of Presence

Albert Serra

The Kind Liar. Some Issues Around Film Criticism Based on the Case Farber/Agee/Schefer

Murielle Joudet

The Termites of Farber: The Image on the Limits of the Craft

Carolina Sourdis

Popcorn and Godard: The Film Criticism of Manny Farber

Andrew Dickos

REVIEW

Coral Cruz. Imágenes narradas. Cómo hacer visible lo invisible en un guión de cine.

Clara Roquet