HYBRID: OUR LIVES TOGETHER1

Robert Walsh

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / ENDNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / ENDNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

2003-2004 brought a cascade of Manny events. It saw the launch of his traveling retrospective, About Face, at San Diego’s Museum of Contemporary Art. He received an award at the San Francisco International Film Festival through the good graces of Tom Luddy and Edith Kramer (both here tonight), whose Pacific Film Archive had been crucial to his teaching life at UCSD. And Espace Négatif, the long-awaited French translation by Brice Matthieussent of his selected film criticism, edited by Patrice Rollet, was published by P.O.L in Paris, where it became the subject of many reviews and interviews with French journalists, as well as a roundtable at the Pompidou. (Though, as Jean-Pierre points out, they employed similar strategies and explored the same terrains, Manny usually needed to be strong-armed into discussing his writing career, which he considered a thing of the past; he was always more than happy to talk about the going concern, painting.)

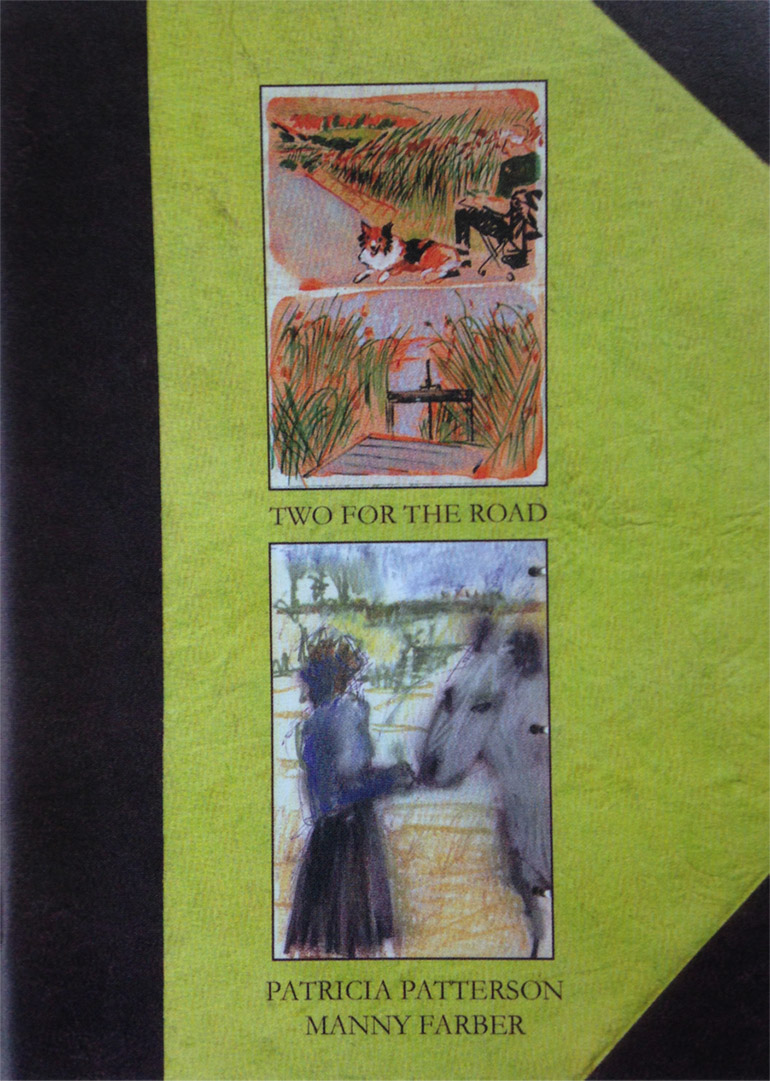

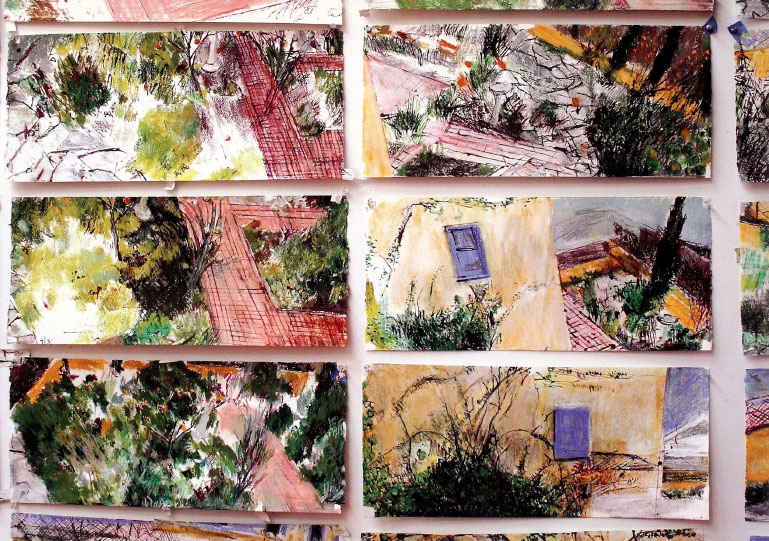

Just before these very public events, and easy to miss, Two for the Road opened at the Athenaeum Music & Arts Library in La Jolla: a small exhibition of Manny’s and Patricia’s sketchbooks, never shown before, their first as a duo.

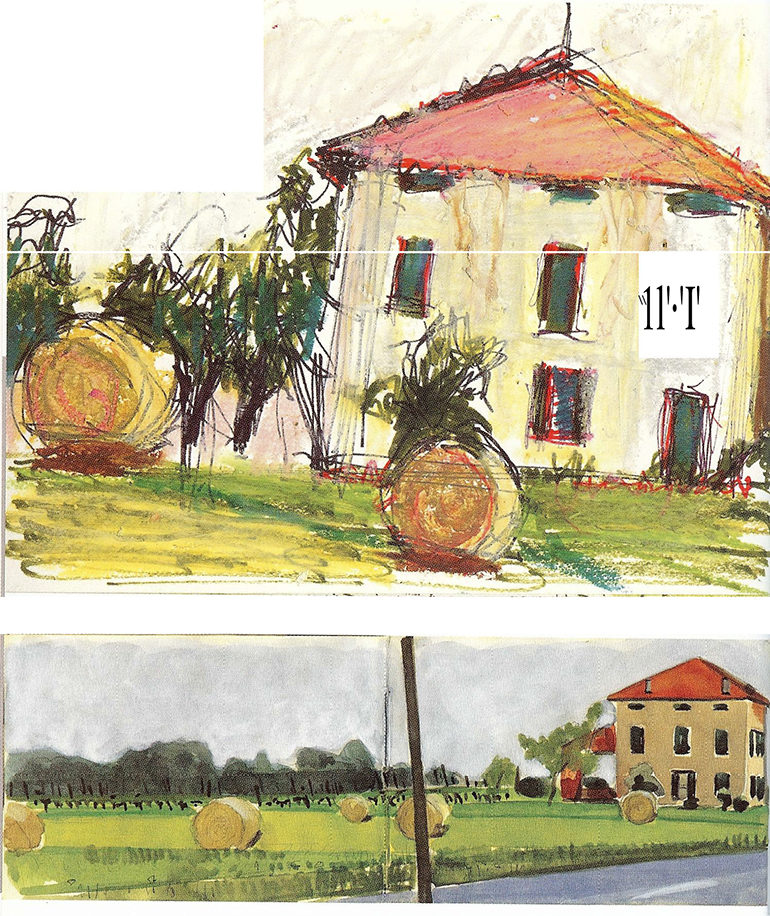

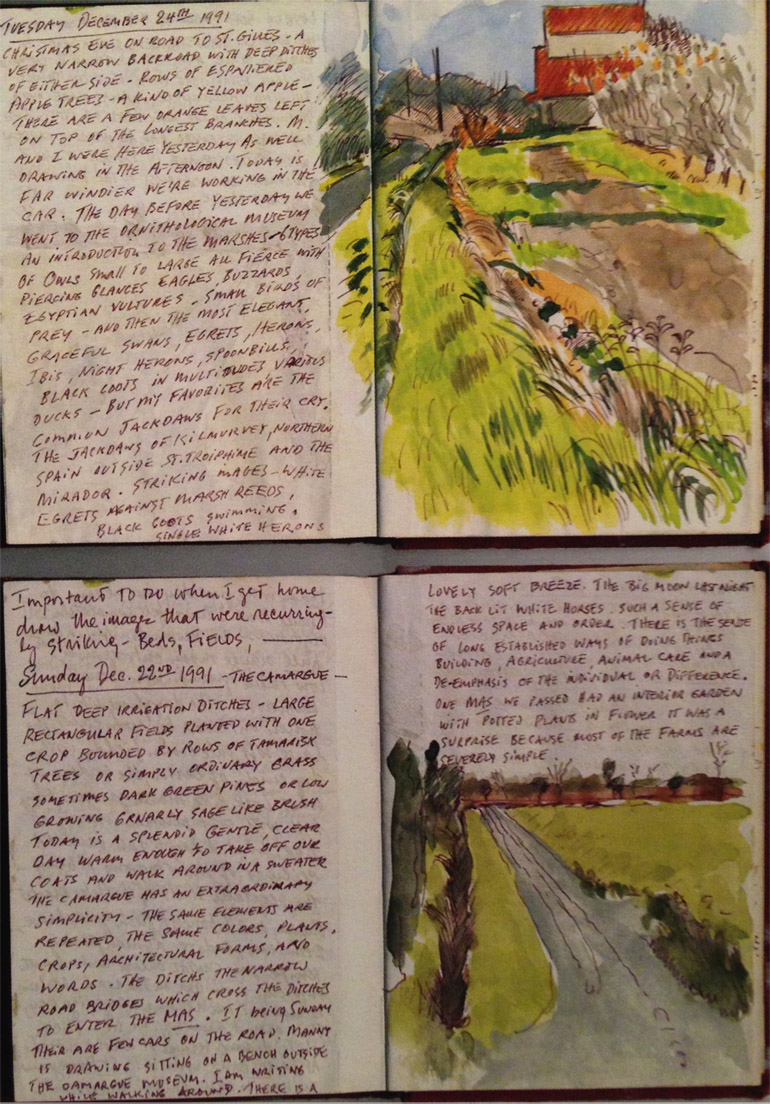

These are a few examples: Patricia’s diary notebooks from the French countryside, just before Christmas 1991, and Manny’s contemporaneous takes on customers in a bar in Arles. There can be no mistaking either’s work for the other’s, even when they sketch the same building. As Manny told Sally Yard, ‘Patricia goes for the psyche, I don’t even touch it—I go for the space.’ (Though Patricia rightfully piped in: ‘So do I.’)

What I’d like to unpack a little tonight—and celebrate—is how, in the deepest sense, all of Manny’s work for the past 40 years has been made in collaboration of one kind or another with Patricia.

*

Two caveats—not lip service, simply incontestable. First, bluntly, that, as Patricia emphasizes, ‘Manny’s work is Manny’s work, it’s his. My name doesn’t deserve to be on it.’ (As we’ll see, Patricia had what she referred to as ‘this other mission.’) Second, that, because of time constraints, Patricia’s own work will be getting short shrift here, and Manny’s influence on Patricia, which he regularly denies, is a topic we won’t get into either.

Plus one additional stipulation: None of what I’ll be saying about Manny’s reliance on Patricia should be considered clandestine or unacknowledged. Only open secrets will be tendered.

*

A bit of history—and geography: In the summer of 1966, on a trip to Cape Cod, Patricia met the photographer and filmmaker Helen Levitt, a friend of Manny’s since the 1940s, who, in an act of instant matchmaking of the highest order, promptly asked Patricia’s permission to put him in touch with her.

Their first date entailed a showing of the rereleased Shane (George Stevens, 1953) at the New Yorker Theater on Manhattan Upper West Side. They entered long after the movie had started—nothing out of the ordinary for him. Twenty minutes or so later, Manny—famously a lifelong early absconder—inevitably said, ‘You’ve seen enough, haven’t you? ‘

Their relationship flourished very quickly: Patricia soon started going to films more often. And leaving them more often.

Within a few months they had rented an unheated loft together on Warren Street in Lower Manhattan. By Manny’s fiftieth birthday, in February 1967, they were living and working together, and their collaboration had begun in earnest.

It’s important to remember where they were in their lives: Manny grew up in Arizona and California. He’d been a painter and critic all of his adult life, and was in the thick of the New York culture scrum. He had already published Underground Movies, Hard-Sell Cinema, White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art, and other essays that made his reputation and continue to saddle him. Judging from the detailed chronology that appears in his catalogues, Manny seems to have known every artist and writer in New York, from the entire Abstract Expressionist circle to the late James Agee and Walker Evans, to Saul Bellow, and Mary McCarthy. He’d had solo exhibitions at Kornblee, where he’d created a groundbreaking gallery-transforming installation in 1962, and Tibor de Nagy. He was attempting to earn a living with freelance carpentry jobs. He and his wife Marsha had separated the year before; he had a nine-year-old daughter, Amanda, herself a painter, sculptor, and teacher in San Diego today.

Patricia, just 25 in 1966, was born and raised in New Jersey, directly across the Hudson River. She’d studied at Parsons School of Design, been greatly encouraged by the legendary Marvin Israel, and traveled in Europe on various art trails; she was an itinerant art teacher in Catholic grade schools in the New York metropolitan area—half-hour classes throughout the day, two thousand kids a week.

About that ‘other mission’ I mentioned…

This is a 1962 shot of Patricia with her Irish friends Nan and Cóilín Mullin by another friend—another photographer—Alen MacWeeney, the basis for her painting called The Three of Us.

By the time she and Manny got involved, Patricia had been visiting and living for long stretches off the western coast of Ireland, on the Aran island of Inishmore—here in the village of Kilmurvey—which became the enduring focus of most of her artwork. She once said that when she returned to New York in 1963 she was stunned by the new ‘bold, large-scale, public work’ of Warhol, Johns, Stella, Oldenburg, et al. She felt that what she herself had been producing was ‘very private, intimate, and romantic.’ In the summer of 1965 she had traveled in Italy and was particularly taken with Piero, Giotto, Fra Angelico—a perfectly poised spot between public and private—evidence of which is clear in most all her work but which didn’t enter Manny’s active painting life until later.

*

Patricia was an outsider to film and in a sense to the New York art world. When they met, Manny was writing for what used to be called, politely, a men’s magazine. And, as Patricia has said, Manny was having a very hard time: He had stopped painting and, barely scraping by with the carpentry, was basically living out of his car. It seems undeniable that, upon meeting Manny, she was thrown into the deep end.

Nonetheless, she swiftly jump-started his working process—in film criticism and painting. The two of them were continuously going to museums, exhibits, and films, and talking, talking. Drafting his articles, Manny took to taking notes and typing as Patricia shared her impressions of the movie they’d just seen—or seen for the fourth time. (This was her immersion in Manny’s habitual method of repeated viewings—much more logistically difficult, time-consuming, and costly in those days than today, as well as contra Kael.)

This is not to imply that Manny was taking dictation; he was gathering intelligence. He would use what Patricia articulated, but argue, reconsider, add lots, cut lots, rewrite, entirely restructure the raw material they were both providing. (If their drafts had been preserved, we would have seen them revising and/or recontextualizing countless opinions. Their article on Godard, for instance, initially much more negative in tone, was among the pieces reworked extensively. Patricia recalls Manny’s saying emphatically that once something was said, it was no longer true).

Having noticed the briefest praise of Manny’s criticism in Susan Sontag’s essay Against Interpretation in the late 1960s, I had come, like most of us, to his writing first and remember being surprised when Patricia mentioned that she was initially unaware of Manny’s importance as a writer. She thought of him primarily as a painter who had dabbled in film criticism, not as one of the major prose stylists, prose thinkers, in America. But that probably accounts for the fact—lucky for him and the rest of us—that she didn’t find the situation utterly daunting. Looking at the essays they did together—starting with a piece for Artforum on the 1967 New York Film Festival (with Patricia uncredited; later articles ran under a shared byline)—one notices several basics:

Although they’re full of the kinds of material and densely layered prose Manny had been cultivating for a long time, these have different ambitions, in part because of a new, art-world audience and fruitful upheaval in global film. Employing shifting points of view and multiple approaches, the essays cunningly flaunt their ambivalences even more than Manny had done on his own. And there is an even fuller blossoming in the early 1970s, once Manny starts teaching film classes at UCSD and he and Patricia are involved with the Pacific Film Archive and the Telluride Film Festival, and especially with Jean-Pierre.

In an endlessly quotable Film Comment interview, Manny told Rick Thompson that he had become ‘very tired of the way the articles in Cavalier and The New Leader sounded’ in the mid-1960s:

‘I hated them. “This is Right and That’s Wrong and There’s Your Movie.” […] With the Artforum work, the terrain and possibilities of criticism suddenly opened up. That’s when I started using a lot of conversation from films. That’s when the collaboration with Patricia started. Her sensibility got involved and seemed legitimate to me; my sensibility for the movies widened’ (FARBER, 1998: 372).

Summing up Patricia’s contributions, he said:

‘Patricia’s got a photographic ear; she remembers conversation from a movie. She is a fierce anti-solutions person, against identifying a movie as one single thing, period. She is also an antagonist of value judgments. What does she replace it with? Relating the movie to other sources, getting the plot, the idea behind the movie—getting the abstract idea out of it. She brings that into the writing and takes the assertiveness out.

In her criticism she’s sort of undergroomed and unsophisticated in one sense, yet the way she sees any work is full-dimension—what its quality is rather than what it attains or what its excellence is; she doesn’t see things in terms of excellence. She has perfect parlance; I’ve never heard her say a clumsy or discordant thing. She talks an incredible line. She also writes it. She does a lot of writing in her art work; she gets the sound related to the actuality in the right posture. It’s very Irish. You don’t feel there’s any padding or aestheticism going on, just the word for the thing or the sentence for the action. I’m almost the opposite of all those qualities: I’m very judgmental, I use a lot of words, I’m very aesthetic-minded, analytic. [...] She cannot be unscrupulous. We have ferocious arguments over every single sentence that’s written’ (FARBER, 1998: 358-359).

Patricia added:

‘If it were up to me I’d never dream of publishing anything—it always seems like work in progress, rough draft. But he’ll say, “Leave it at that.” ‘ (FARBER, 1998: 358).

*

As significant as the writing of the late 1960s was the creation of Manny’s large paper process-abstractions, which grew out of easel-size paper paintings that he stenciled and wrote on, and which engaged him artistically for the next several years.

Patricia was not only not an abstract artist; she was more attached to art of the past, the immediate and the long past, while Manny’s influences and dialogues at that stage were primarily with his contemporaries. ‘When artists would come around,’ she once said, ‘there was no question that they thought what he was doing was serious and what I was doing was not.’ Yet she was averse to the notion of giving up her representational work and couldn’t quite imagine herself into the art world.

Nonetheless, she plunged into the studio work with Manny. She would stand atop a ladder and indicate to him the proper contour to be sliced from collaged Kraft paper. Through trial and error, they came up with very elaborate techniques for saturating the paper, mixing, applying and drying the paints, flipping the double-sided works during a period of hours or days. After they had moved further uptown but were keeping the Warren Street studio, Manny would tramp down dozens of city blocks through the snow in the middle of the night simply to turn a sheet over.

Patricia always saw Manny as the brave one, more ambitious in the art world, more competitive with his peers, driven, the prime mover. He had enormous stamina, a capacity for unflagging toil. (These days Manny’s big gripe seems to be that the chief drawback of aging is his inability to do as much work as he’d like. His unfollowable advice to Jean-Pierre: ‘Don’t get old.’)

From the beginning more hesitant, tentative, and needing more sleep, Patricia felt a certain relief at working with Manny behind the scenes. She was comfortable avoiding the complications of joint credit in the art world and antagonistic to its Reign of Titans. Part of her input involved the slow, methodical development of her aesthetic—through issues of scale, technique, speed of effects, subject matter—which Manny could—and did—assimilate and build upon as he wished. (I’ll come back to this…)

*

This account brings us far too abruptly to Manny’s stylistic shift of 1974, for which Patricia credits ‘changes in the art world when more autobiographical, representational work became respectable and legitimate again,’ rather than her own influence. Manny’s film classes had already begun to focus on everyday domesticity in a range of films, from silent comedies to Wellman to Ozu. And Patricia remembers ‘arguing Manny into stuff’ at the 1972 Venice Film Festival, specifically concerning Fassbinder and Straub-Huillet, filmmakers he would regularly lecture on until his retirement.

You can hear the blend of their sensibilities in this extract, where they refer to Hans in The Merchant of Four Seasons (Händler der vier Jahreszeiten, Rainer Warner Fassbinder, 1971) as

‘a victim in a modern Matisse image of four orchard-fresh colors [...] Fassbinder makes a wholesome frontal image in many ways like small Fra Angelico panels: a man in a crisp blue-and-white plaid shirt hawking the pale green pears filling a rectangular cart, a humble action frozen in a shallow-still composition’ (FARBER, 2009: 707).

*

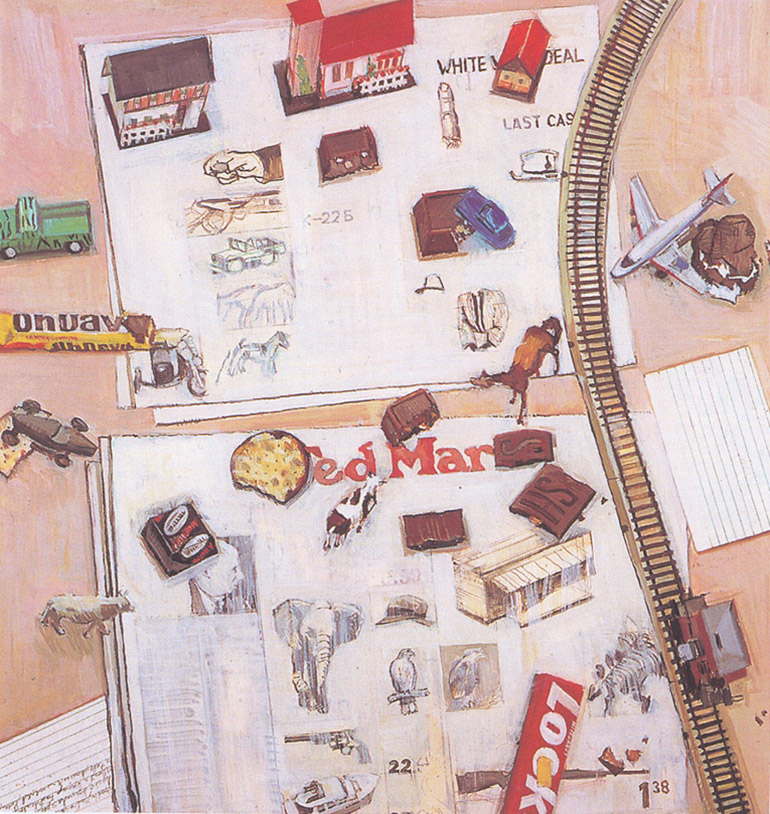

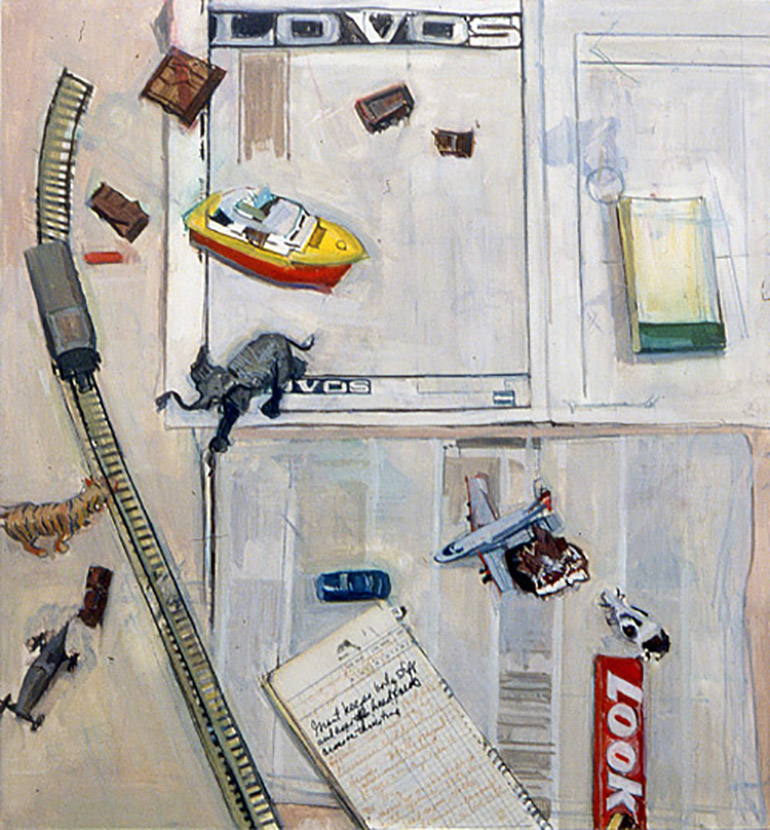

Howard Hawks II, from 1977: an oil-on-paper companion piece to A Dandy’s Gesture (each less than two-feet-square), which Patrick Amos and Jean-Pierre have discussed in their indispensable 1985 essay, The Farber Machine.

Jean-Pierre and Amos’s comments, such as

The objects in the painting… provide a crash course in Howard Hawks’ genre-bound career—the tiger is from Hatari (1962), the plane from Only Angels Have Wings (1939), the newspaper layout from His Girl Friday (1940)—but they now animate the space of the painting and establish their own autonomous fictional terrain.

With the new disparity of scales and objects Farber can better impose a system of reading that mixes different densities of information and constantly shifts gears and speeds across the painting.» (AMOS AND GORIN, 1986).

—as well as those about the mind of the bricoleur, are just as telling about Hawks II and the strategies and tactics Manny would deploy in the works that followed.

Manny had been restless with abstraction, and believed he had come to the end of a long run by 1974. He found a new absorption in the so-called “narrative,” “still-life,” “tabletop” paintings.

There was an extremely fast progression from Manny’s first forays with start-from-scratch drawings of tools, to the American Candy series, American Stationery, and on to the Auteurs in just three years. Surveying the first decade of the figurative phase—maybe we should call it the post-abstract-process phase—J.-P. and Amos alert us to Manny’s ‘compulsive need to bring each move to a standstill by producing immediately next to it a critical counter-move» and a debate between ‘his rhetorical longing for jazzing improvisations and his constantly affirmed need for tight compositional planning’ (AMOS y GORIN, 1985).

Even in a lap-size work like Hawks II you’ll notice the depictions of animals (toy animals from an aerial perspective in his case) that Manny has always thought Patricia just nails. The three series introduce and advance a local feel, domestic elements, versions of other images (movie stills, art reproductions, etc.), enormous detail, but nothing cramped or overdone.

Though the multiple angles and shifting scale are all his own, there’s an openness that Manny agrees has been one of Patricia’s abiding concerns. In these and in the later large palette-knife oils on board, he would show himself capable of exceptionally painstaking, time-intensive works in several figurative modes, even down to painting, in Patricia’s words, ‘the shadow under a raisin.’ She occasionally thought his complex, overall compositions could use some air. Over the years, she has suggested that he ceases work on a particular painting at a point he might not have been inclined to on his own—and he’s spoken gratefully of her having saved him from himself. The fact that he could see more he could do didn’t mean he should do it.

‘Leave it as it is. Leave it at that.’

Not to put too fine a point on it, but there was clearly a role reversal here: Manny was usually trying not to overburden, belabor the film criticism; despite the wealth of detail, he was going for speed. As his paintings became capable of accommodating anything and everything in his purview, Patricia helped him maintain a legible profusion, without drowning in William James’s ‘blooming, buzzing confusion.’

*

One cog of the first Farber-Hawks machine, less prominent here, is Manny’s handwritten messaging—another area where Patricia had a large role.

‘I really like using words,’ she once said about her own installations, which had deployed song lyrics and conversations in striking configurations. ‘I like the way words look.’

As I’ve indicated, Manny was particularly taken with Patricia’s ear and the time-layering that incorporation of movie dialogue contributed to the criticism. For the so-called “diaristic” paintings from 1974 on, he would appropriate snatches of dialogue—such as ‘feeding four flies, a glass of milk, and one piece of white bread to a snake’ from The Lady Eve (Preston Sturges, 1941)—and ventriloquize slogans, directives, stray remarks, from Patricia (and others), using them as apparently “self-targeted” (in J.-P. and Amos’s phrase) notes to himself. As they go on to say:

‘these missives allow Farber to describe, in a delirium of accumulation, how the painting was painted; how it should or might be read; how the next one should, might, could be done.’

But who is talking in these unattributed texts? Who is doing the talking?

Do Flower Near Vase.

Get It Finished.

No More Film. (Something Patricia felt increasingly in the mid-Seventies.)

What’s Wrong With Off the Top of the Head?

Put This Figure Upside Down.

Don’t Panic.

Don’t think so much.

Holier Than Thou.

Keep Showing Women Working.

Leave a lot of yellow and blue.

Don’t be so heavy and serious.

Go easy on violence and meanness.

I Want This Room Filled with Flowers.

Keep blaming everyone.

And my favorite: Easily intimidated.

How often was he lip-synching? How often responding to whispered questions or repeating phrases fed to him, like the actor-characters in 1960s Godard?

Who was talking? Only the painting, as the site of a disguised duet, a veiled polyphony.

*

1977, the year of theHawks paintings, was the year of that Film Comment interview, in which Manny and Patricia discussed the state of film criticism and recent art world strategies, his teaching methods, and ‘creeps getting their just due.’ The year, too, of Kitchen without Kitsch, sadly the last of their essays—on Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman (1975), a model work of Patricia’s hieratic domesticity.

The piece begins this way—and the links to Manny’s own work are blatant:

‘The lay of the land, in the Seventies film, is that there are two types of structure being practiced: dispersal and shallow-boxed space. Rameau’s Nephew (Michael Snow, 1974), McCabe and Mrs. Miller (Robert Altman, 1971), Celine and Julie Go Boating (Céline et Julie vont en bateau, Jacques Rivette, 1974), Beware of a Holy Whore(Warnung vor einer heiligen Nutte, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1971) are films that believe implicitly in the idea of non-solidity, that everything is a mass of energy particles, and the aim, structurally, is a flux-like space to go with the atomized content and the idea of keeping the freshness and energy of the real world within the movie’s frame. Inconclusiveness is a big quality in the seventies: never give the whole picture, the last word.’

Manny and Patricia allude to a host of filmmakers—from Robert Frank and Yvonne Rainer to Michael Snow, Ozu, the Straubs, Bresson, Buñuel, Warhol—and end by revisiting some of Manny’s longtime themes while moving into Patricia’s territory:

‘Though somewhat pat in comparison to its fiercer influences […] [How much is packed into that short phrase?] the Akerman revelation is a political thrust against the box-office hype of the straight press, which has convinced the audience that it needs Vito Corleones, Johnny Guitars, or Carries, constant juicing, dramatic rises and falls for its satisfaction. The audience has been brainwashed to believe it can’t stand certain experiences, thanks to the Mekas propaganda wheel as well as media hypesters.

Watching the luminously magical space of a washing-smoothing-cooking-slicing-kneading near-peasant is particularly provocative in that it suggests a workable parlance between structural and commercial film.’

These concerns—and the extrapolations to their artwork—continued to inform Manny’s and Patricia’s painting.

Manny concluded the Film Comment interview by telling Thompson:

‘I work at painting, but no more than at criticism. Painting comes natural! […] I can’t imagine a more perfect art form, a more perfect career than criticism. I can’t imagine anything more valuable to do, and I’ve always felt that way.’

He continued teaching for another ten years, but, aside from observations in interviews, these were his—their—final published words on film, on writing.

*

Resetting the clocks, as our master of ceremonies and DJ Jean-Pierre urged us to do, let me reverse gears and switch tracks:

In passing, Manny had also told Thompson about Godard’s visit to his studio:

‘I loved him, he was terrific, but I don’t know what he said. I know how he looked. The Straubs were awful, I could have killed them.’

This impulse didn’t keep him from painting a major work two years later: Thinking about “History Lessons”, a painting Jean-Pierre has the chance to view on an almost daily basis, and which Manny described as featuring obvious and crude sexuality, in an anti-Straub, anti-cerebral materialist move.

In a 1982 interview with Cahiers du Cinéma, Manny said:

‘Painting is like writing. It allows me to approach a film from several angles. The motivation of my painting, and much of my critical writing is to try to reconstitute the different feelings suggested in the film. It’s a pluralist vision…’

‘I don’t think anyone can decipher what these paintings of mine are dealing with…’

‘In order to capture the complex dimensions of a given subject, it’s essential to include as many references and perspectives as possible. The relation of a character to a table, to the ground, to a house, or a train, shouldn’t obey one logic; it should be infinite.’

‘Often what I do is the opposite of what is expected. So my Straub-Huillet painting is filled with erotic content because I know it will startle people; Straub-Huillet are very austere, only interested in serious things, so I shake up the audience by showing something they weren’t expecting in connection with their work.’ (GORIN, J.-P, y ASSAYAS, O., LE PÉRÓN, S. y TOUBIANA, S. 1982: 54).

J.-P and Amos contend that, ‘The move allows Farber to have it both ways: to show the viewer the essence of their aesthetic and to produce next to it precisely what it leaves out.’ And in the most incisive analysis of Manny’s painting, they continue:

‘What the minimalist visual aesthetic of the Straubs denies is precisely what Farber sees as the power of the film image. He insists on the film image’s transformative nature. He sees it as movement, as never resting on itself, always leaking at the edge, always creating the need for another shot, another image, always existing as a switching device to route and reroute attention. What underlies Farber’s figurative work is his attempt to revitalize painting by importing the dynamic of the film image. Thus the refusal of his pictures to coalesce into single images; their contentious relationship with any centrality, their multiplications of compositional strategies and viewpoints; their multivalent appropriations; their dependence on paths, routes, networks, and the painter’s insistence on a nomadic reading of his boards.’ (AMOS y GORIN, 1985).

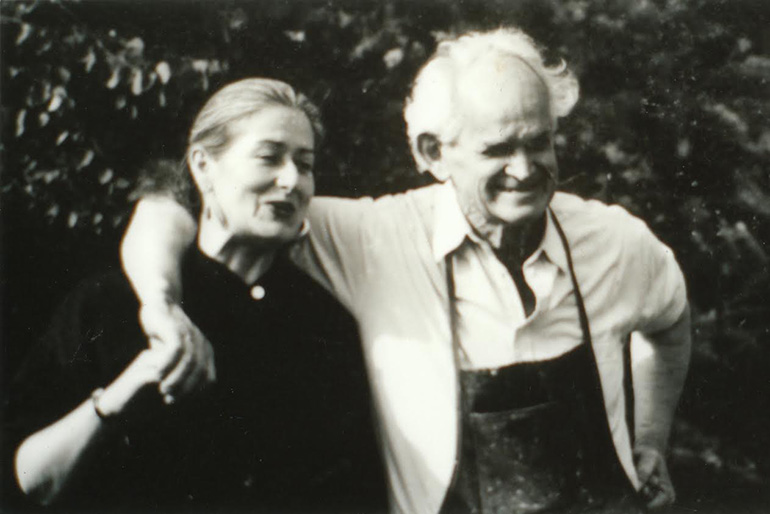

A parenthesis: In keeping with the trope of ventriloquism, as well as Manny’s penchant for autobiographical subtext, I can’t help but see this version of a photograph of Straub and Huillet, taken from Richard Roud’s book about the filmmakers, by analogy as a double portrait of Manny and Patricia?

*

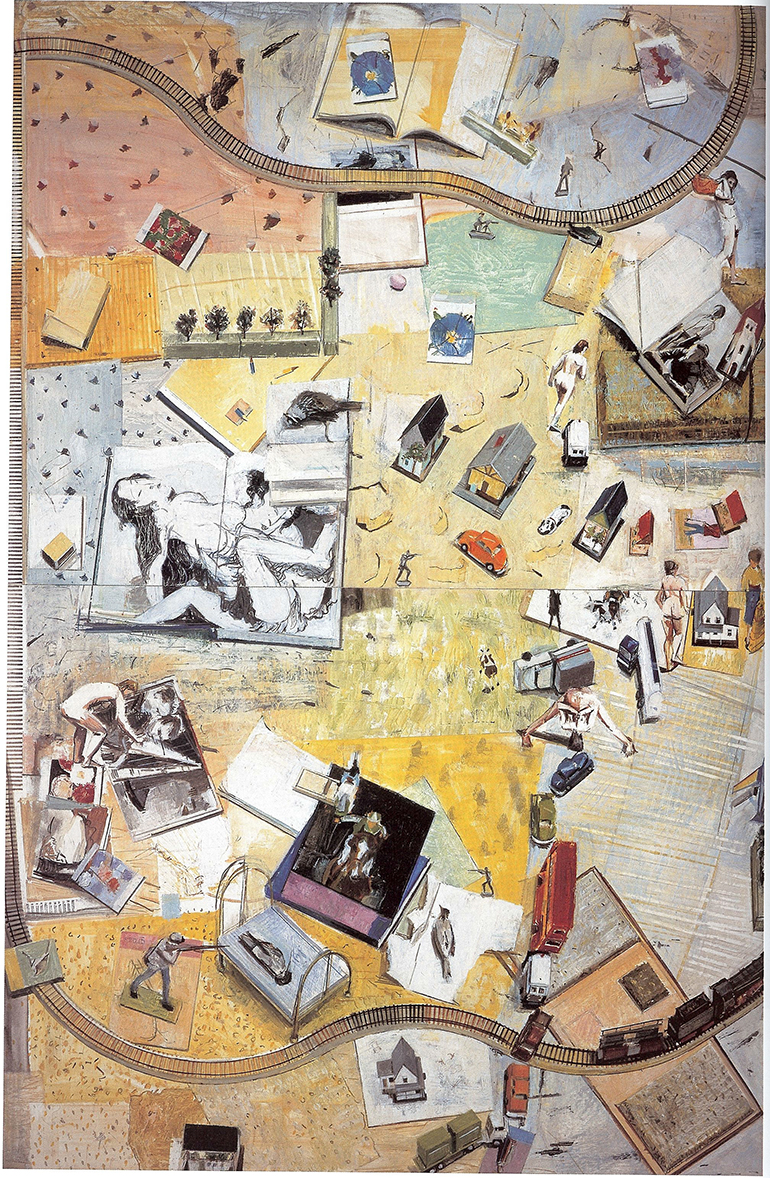

In 1985 came a painting actually called Domestic Movies, six-feet square, which incorporates ticker-tape-like film-leader messages referring to works Manny had taught, including Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955), Stella Dallas (King Vidor, 1937), and The Honeymoon Killers (Leonard Kastle, 1969). With its enormous size, its abutted bright-color fields and exactingly executed passages in a range of styles, it can be seen as one culmination of the previous ten years and—with its profusion of flowers, birds, and food, and its counterbalancing improvisatory arabesques—presaged much of Manny’s work of the next twenty.

The two-color background panes—Patricia’s choice—echo the striking pigment combinations she was using for the framing of her own work, but in Manny’s paintings, these function differently, and all the more so in the extended series of works with black-and-white grounds that would follow: They call attention to the deliberate constructedness of each painting, creating separate zones of space and time, strictly defined arenas where ping-ponging improvisation can thrive.

Each border crossing, each opportunity to respond to another framing edge—notice the number of internal rectangles—highlights Manny’s pervasive strategy of slowing down the viewer, even halting you dead in your tracks (as he would accomplish with lengthy texts placed at odd angles). He had employed this boundary technique in much of his abstract expressionist painting and sculpture, long before the barely concealed grids of the paper paintings, which the late, much lamented critic Amy Goldin dubbed «the bones.»

Working with and against Patricia’s dramatic, brilliant color sense freed Manny to explore further, and in a novel context, the kinds of color he had created in the paper paintings and in the early figurative works. Goldin refered to it as ‘color that looks as if it’s been through a lot: abraded, drowned, rising to the surface, floating. Light-sensitive color that has been subjected to natural phenomena.’

‘Of all Farber’s paintings,’ J.-P. and Amos concluded, ‘Domestic Movies has the most aggressive and disparate palette.’ They went on to make this precise breakdown:

‘What was lateral displacement [in the early series] is now vertical, what was separateness and fixed borders is now entanglement and snarl; what was linear alignment is flow; what was network is mesh. And what existed between then-and-now is cast in the present tense.’ (AMOS & GORIN, 1985).

*

Often executed at speed with casein on canvas (following long preparation) and employing the strictest economy of means, much of Patricia’s work has achieved an oxymoron of sorts: preserved and instantly readable moments of emotionally complex purity, whose unpretentious but theatrically iconic stature resonates with other equally unpretentious and iconic moments in separate works. There’s nothing quite like taking a 360-degree pan of one of her installation spaces. Each of her Aran-related images and objects invites us to assemble in our minds an abundantly, intimately populated world elsewhere.

As Patricia would be the first to acknowledge, the rhythms and musicality, the time-coding of Manny’s work, are all his. The sense of an intricately faceted temporal process is always paramount; one’s first, instantaneous take—that sense of stunning simultaneity, resulting from montage—works off and emphasizes it. Taking any seemingly random path through even one of his most dizzyingly complex paintings, you soon discover that he has already been everywhere along the route, anticipated and orchestrated where and how you’re likely proceed and perch.

The force fields of Manny’s paintings since 1974 had operated by similarities, analogies, variations, resonance-dissonance within dispersal. Gradually, each depiction of an object (a pear, a length of rebar, an open art volume) as well as the increasingly abstract “underpainting” of the ground, came to have its own image-voice, which resonates with other image-voices. The painter’s I—Manny’s I—encounters the Thou of an object, and the I of each image he makes invariably speaks with at least one other Thou. It is as though each object, not simply exists with, but experiences the others, and a painting is their polyphonic song. Since Godard has already taken the phrase Notre Musique, let’s call the works Our Lives Together. (With a distant reverb of Tangled Up in Blue‘s next phrase, ‘Sure was gonna be rough.’)

*

Second and Final Parenthesis: I don’t want to sentimentalize this process or sand down the rough bits, though I’ve likely done both. Where is the conflict?, you might ask.

Let me float this unsweet notion: that, for all his love and admiration for Patricia’s work, much of Manny’s painting from ‘74 to ‘87 or so amounted to an answer to—and at times even an aggressive micro-critique-in-action of—Patricia’s aesthetic.

Stillness, compassion, singular moments steeped in local and art history, paintings based on photographs and other documentation, a community of actual living people in a far-off country: What could be more radically different from the own work of that period by an artist whose method, according to J.-P. and Amos

‘denies the possibility of closure, of resolution, of completion, who is forever adding one more twist, who seems reluctant to move on to another painting because he is always seeing the possibility of further connections in the one underway.’ (AMOS & GORIN, 1985).

*

Since 1970, when he and Patricia moved to Southern California, Manny’s everyday life had been a continuous round of film classes, painting, watching reels and taking notes, catnapping, painting, film classes, etc.

In 1987, after he and Patricia had been a couple for more than twenty years, Manny, having turned 70, stepped down from teaching and began to work under the daily influence of: natural light, which flooded his studio at home (much of the earlier work was done entirely under fluorescents); a more settled domestic routine, which featured fewer sleepless or interrupted nights spent preparing for class; less film-going and less film talk; more and different kinds of music in the studio (Pollini, René Jacobs, Jon Hassell); more walks with Patricia, which brought the lagoon landscape into his paintings by way of twigs, eggs, feathers, and other plunder en route; and, above all, the inestimable presence of her ever-changing garden.

Manny’s obsession, especially once he had stopped writing and teaching film, has been his relating everything to his work. ‘Mallarmé said that everything in the world exists in order to end in a book,’ Sontag wrote. ‘Today everything exists to end in a photograph.’ For Manny, painting is all.

So Patricia would literally take him by the hand into the garden and on their walks, suggesting what he might paint next.

She said in 1989 that her ‘painting is related to things like gardening and designing a studio and reading… And now Manny and I talk even more about making, inside-painting kinds of things—color choices, scale decisions, framing moves, what to put next to what and why’ (PATTERSON, P. & WALSH, R.: 1989).

Their shared domestic environ became his sole subject matter, and though I can’t go into it here, I’d suggest that, rather than critiquing Patricia’s aesthetic, Manny’s work post-retirement came more and more to include and accept it, blend it with his own. “Topic for future research”, as the saying goes.

*

Which leads us, as in Finnegans Wake, ‘by a commodius vicus of recirculation’ back to Patricia’s in-the-meantime, meanwhile mission:

Through almost thirty years of teaching, two devastating fires ten years apart, in which she lost, first, nearly all and then ‘only two-thirds’ of her work, Patricia continued her own artistic practice. Until her retirement in 1999, her university duties included classes in painting and drawing, as well as art history lectures, notably a course on the Shakers, the Bauhaus, De Stijl, and Russian Constructivism—the art and politics of utopian communities.

There have been many other projects as well, such as public gardens, the color scheme for the San Diego Children’s Museum, and the enlivening “treatment” of small house in Tijuana.

But the core material of her art, its core space, has always been, and remains today, the Aran work—paintings, drawings, installations including Irish songs and conversation, all concerned with the residents, objects, and other ingredients of that world: a kitchen stove and cupboard, a piebald pony, the “skyline” of a tiny windswept village like another bare stone wall. The goal, however, throughout her career, has been to make the work pristinely contemporary, no matter what the subject matter. Traditional at first glance, every inch an art of the past—an art with the past—but by emphasizing the theatricality of people in rooms, like characters in a play, she was blending Aran with Fassbinder and the Straubs.

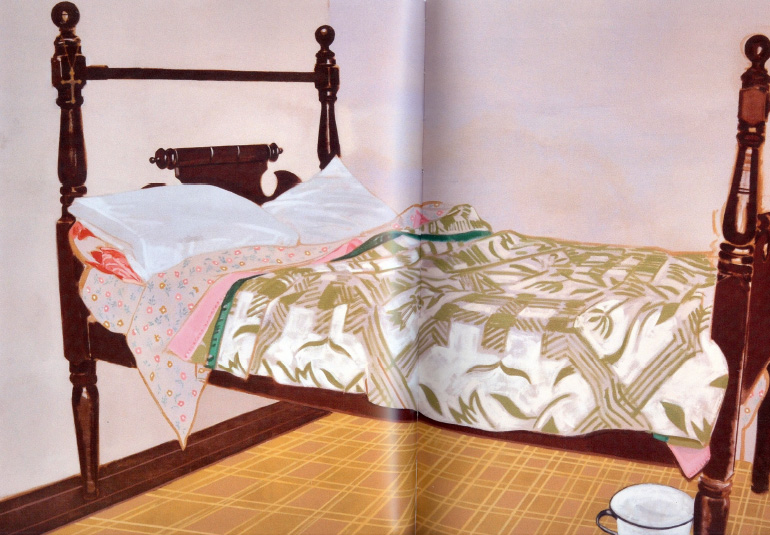

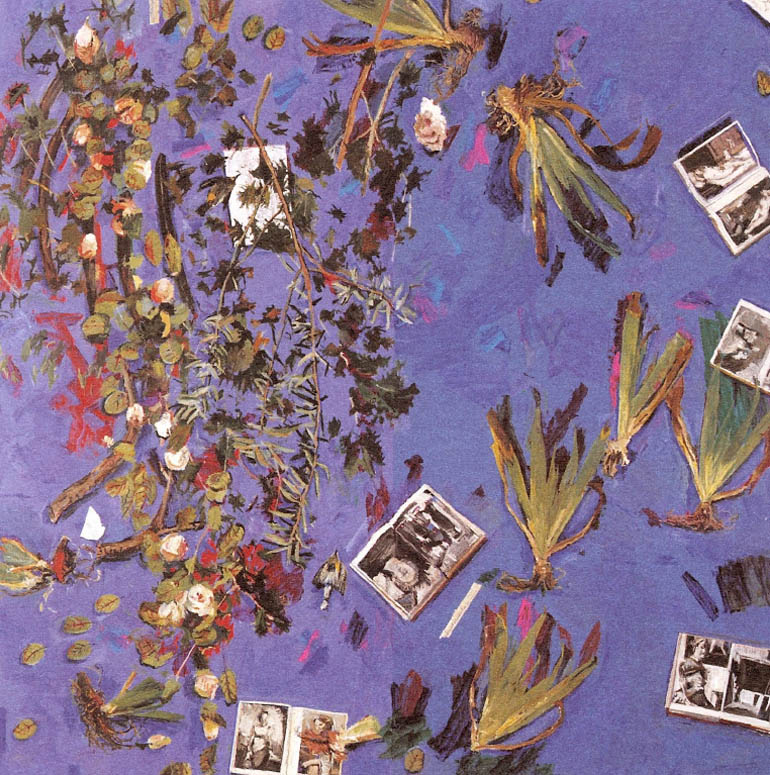

These are paintings—my hurried selection—that she exhibited in the early 1990s at Palomar College’s Boehm Gallery, nearby in San Marcos, part of an installation coming to grips with the death of her Aran friend Pat Hernan…

The marriage bed, a couple’s lifelong domestic site.

Pat’s wife, Mary, alone and in mourning. He had died two weeks before.

Pat’s grave.

A winter vegetable garden: tender green shoots, dark earth, the rhythm of things growing.

(I can almost hear Manny, who’s never been to Aran either, warning me I’m getting cornier by the minute, but for the time being, enough has accurately articulated—by Jean-Pierre and others—about stratagems and documentation, etc.)

The question is: What do these bare, luminous images show us?

Love, loss, a life lived together.

*

Toward the end of the millennium the critic-novelist-translator Gilbert Adair wrote:

‘there once existed critics who actually helped form public taste, who changed things, who made things happen, who “created a climate.” […] In the United States there was in the past the magnificent Manny Farber.’

Manny certainly accomplished those tasks, at the very least. But what Patricia has done and does for Manny is that and more: the direct and personal creation of the climate most conducive to the growth of his work.

These days the garden is taking over the studio… providing the opening moves of future Manny paintings.

To close, from 2000, one of the glorious masterpieces (a term he himself would wave off) of Manny’s most recent phase, Ingenious Zeus—yet another from a preponderance of titles originating with Patricia. Vegetables, roses from the garden, a clipped branch of shimmering leaves, a puzzling note, is it?, in the upper right corner (often Manny’s endpoint, his sweet spot, the place his zigzag vectors mysteriously lead us).

In reproduction: the Pieros, Vermeer’s Woman at the Virginal, Corot’s Italian Women, Titian’s nudes—all suggested by Patricia. Out of frame, in the painting’s negative space and time, the story of yet another of Zeus’s seductions (Danae this time), his appearance as a shower of coins, and all the renderings of that myth by earlier artists: Rembrandt, Van Dyck, Tintoretto, and several other Titians—even a Klimt.

As I look at it, Manny’s major yearning/need/aspiration/maneuver, maybe even his function, has been to see, reach out, and deal with something/anything, directly, with his hands, to respond to something/anything immediately before him—whether a film or items he’s in the middle of arranging on a table—project himself into it, and remake/reconstruct his responses and himself—remaking as both altering and doing over again. Writing “criticism,” process paintings, teaching, “still-lifes.” Work, in other words, the unavoidable, polyvalent term when talking about Manny. Not work as in exploitation—a meme you don’t hear too much these days but which will probably be making a comeback—but work as labor, as constructed object. Work, which Jean-Pierre calls Manny’s only religion. Which implies that, whatever he’s up to, Manny is furthering a lifelong project, continuing his devotions.

Everything he touches is worked—worked off and over, around, out, and through, up and in—and reworked again. He responds most fully, in the round, to Patricia, to her words, her silences, her aversions, her empathies, her garden, herwork. She has been his defining negative space for more than forty years. The I-Thou relationship he talks of entering into with his subjects, cultivating, so that they are given their due, is a stand-in, a surrogate relationship with her.

From the very beginning, their relationship was rooted in, built upon, and managed to survive working together.

Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville used to make repeated reference in films such as Sauve qui peut(la vie) (1980) and Passion (1982) to a longed-for fusion of love and work. Sometimes a bit rhetorical, a mask one puts on, pretending to be someone else; sometimes truly assuming the virtue.

In this light, Manny and Patricia’s partnership has been ideal, exemplary (that overused but necessary word): Exploring love and work in their shifting adjustments and adaptations; making work, trying to keep your work your love, and love your spontaneous and lasting work, in full commitment. Like the scores of elements, including chance, brought to life in Manny’s paintings—Patricia’s radiant colors set against his scumbled varieties, an old toy, a snippet of dialogue, a nastertium in every phase of its life from seed to dried husk, a Giotto, a Goya—everything’s within your grasp, to be reworked, loved, again and again.

Postscript: Despite debilitating illness, Manny continued working for another two years following the All That Jazz event. He left us with fewer vast paintings but produced an unexpected and entirely stunning series of sculptural pastels, exhibited as Drawing Across Time shortly before his death in August 2008. The subject: nearly 70 views of Patricia’s garden.

In Memoriam Manny, Zachary, Chris

ENDNOTES

1 / A truncated-on-the-fly version of this presentation was delivered as part of Manny Farber & All That Jazz, a five-hour tribute-circus curated by his friend and tireless champion, his dharma heir so to speak, Jean-Pierre Gorin, at the University of California, San Diego in 2006.

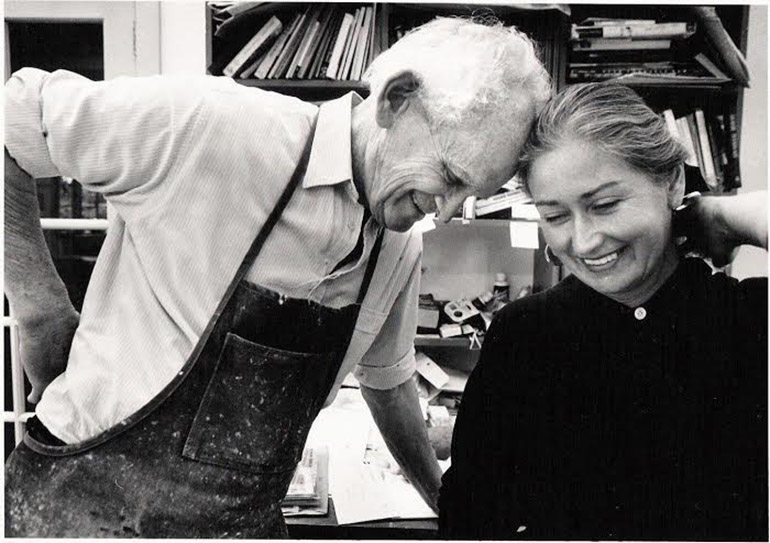

PHOTO CREDITS

The Three of Us photo is by Alen MacWeeney

The image of Manny in the doorway and Patricia seated is by Sheila Paige.

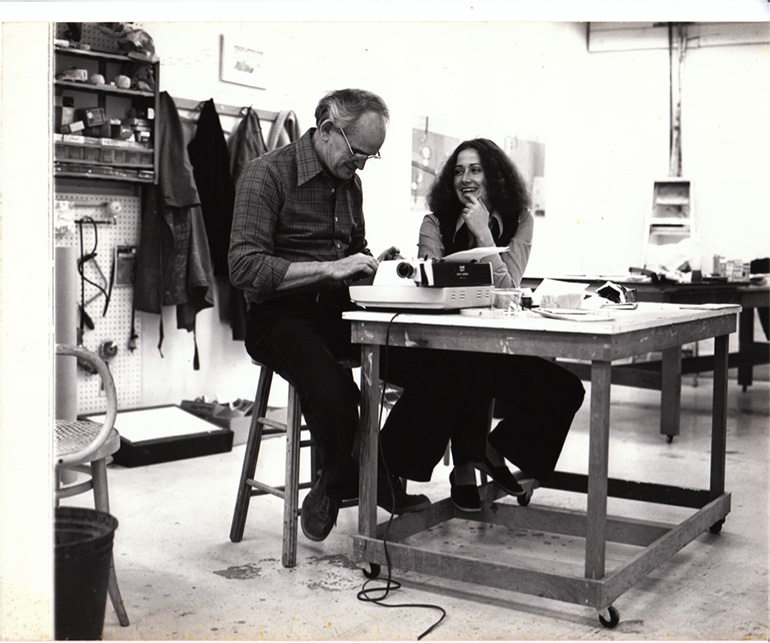

Manny and Patricia at the desk at UCSD is by Becky Cohen.

The black and white images of the two of them in the garden and with their heads together are by Don Boomer.

Manny at the table in the garden is by Michelle Darnell.

ABSTRACT

This article examines Manny Farber’s career path and the stylistic changes stimulated by the arrival of Patricia Patterson in his life, with the opening of a sensibility revealed in different stages of his work. The essay reflects on the influences their relationship had on Farber’s methodologies, techniques, and the overall aesthetics of his critical and pictorial work.

KEYWORDS

Manny Farber, Patricia Patterson, Film criticism, shifting points of view, color, film image’s transformative nature, Jean-Pierre Gorin, work.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AMOS, Patrick & GORIN, Jean-Pierre (1985). The Farber Machine. Manny Farber. Los Angeles. The Museum of Contemporary Art. Exhibition Catalogue. November 12, 1985 - February 9, 1986; Art in America 74, nº 4 (April 1986), pp. 176-85, 207.

http://www.rouge.com.au/12/farber_amos_gorin.html

FARBER, Manny (1998). Negative Space. Manny Farber on the Movies. Expanded Edition. New York. Da Capo Press.

FARBER, Manny (2009). Farber on Film. The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber. POLITO, Robert (Ed.). New York. The Library of America.

GORIN, Jean-Pierre, & ASSAYAS, Olivier, LE PÉRÓN, Serge & TOUBIANA, Serge (1982). Manny Farber. Critique et peintre du cinéma. Cahiers du Cinéma, nº 334/335, abril, pp. 54-63, 130. An English translation by Noel King appeared in Framework, Vol. 40, April 1999, pp. 35-51.

PATTERSON, Patricia & WALSH, Robert (1989). Local Color. Interview, May, pp. 80-84, 128.

ROBERT WALSH

Has been an editor at Vanity Fair for more than two decades. He has also worked closely with Susan Sontag, Pauline Kael, Joseph McElroy, and Harold Brodkey. He was the editor of the expanded edition of Negative Space: Manny Farber on the Movies (1998), as well as a contributor to the catalogue for Farber’s About Face retrospective (2003), Jean-Pierre Gorin’s All That Jazz tribute to Farber (2006), and the catalogue for Patricia Patterson’s Here and There, Back and Forth retrospective (2011). He has published criticism in Art in America, ArtNews, and Facing Texts: Encounters Between Contemporary Writers and Critics (1998).

Nº 4 MANNY FARBER: SYSTEMS OF MOVEMENT

Editorial

Gonzalo de Lucas

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEW

The Law of the Frame

Jean-Pierre Gorin & Kent Jones

DOCUMENTS. 4 ARTICLES BY FARBER

The Gimp

Manny Farber

Ozu's Films

Manny Farber

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Manny Farber & Patricia Patterson

Nearer My Agee to Thee (1965)

Manny Farber

DOCUMENTS. INTRODUCTIONS TO MANNY FARBER

Introduction to 'White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art and Other Writings on Film'

José Luis Guarner

Termite Makes Right. The Subterranean Criticism of Manny Farber

Jim Hoberman

Preface to 'Negative Space'

Robert Walsh

Other Roads, Other Tracks

Robert Polito

The Filmic Space According to Farber

Patrice Rollet

ARTICLES

Hybrid: Our Lives Together

Robert Walsh

The Dramaturgy of Presence

Albert Serra

The Kind Liar. Some Issues Around Film Criticism Based on the Case Farber/Agee/Schefer

Murielle Joudet

The Termites of Farber: The Image on the Limits of the Craft

Carolina Sourdis

Popcorn and Godard: The Film Criticism of Manny Farber

Andrew Dickos

REVIEW

Coral Cruz. Imágenes narradas. Cómo hacer visible lo invisible en un guión de cine.

Clara Roquet