THE DRAMATURGY OF PRESENCE

Albert Serra

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Films are about personality: the better the personality, the better the film.

Paul Morrissey

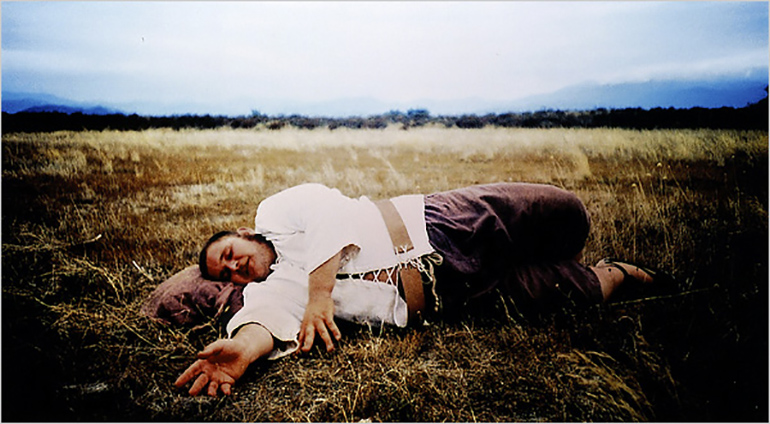

The recovery of the actor as a performer, as a generator of unrepeatable and fatal gestures, as a creator of human destiny and plastic to time, has been my obsession since I started to work on cinema. Manny Farber, like Warhol and Paul Morrissey, detected the beginning of the decline of the actor in the 1950’s. They longed the cinema of the 1930’s, where the look of the actor was still more important than the hairstyle (a ‘baluster’), the gesture than its meaning. All the stylization of the film was upon the actor’s service, and not the other way around. (The lighting was not an abstract thing arisen from the cinematographer’s imagination; it highlighted the face of the actors!). Hence Paulette Goddard’s terrible comment about the decline of Chaplin, when ‘Max Eastman and Upton Sinclair ruined Charlie, by intellectualizing what he did, and then he couldn’t do it anymore’. Paulette, Chaplin’s wife, portrays him as a frustrated writer who, facing his own incapability with the written language, decides to make literature with images. The presence of the actor was lost (‘before, his movies were all about movement, movement and mime’), and the signified appeared. Hence the predilection of all the avant-garde art for the mechanic purity of Keaton, for the wild and savage purity of Harry Langdon, or in the case of Manny Farber, for Laurel and Hardy: Their staging was, according to him, “dispersed” (FABER, 1998: 370), and instead of being virtuous deploying space –like Chaplin- they ‘dissolved’ it around them; Laurel and Hardy are lost in their own frame, and in a disturbing way, they do not know how to use it ‘aesthetically or egoistically’ (FARBER, 1998: 370) towards their own benefit.

***

All the advances related to staging in film history have had a narrative purpose. I have always considered absurd to think about the staging, and I have avoided believing that it could have any relevance to the aesthetic quality of the film. I have shot in digital, because it was more simple to serve the actor, and all my method comes down to the principle that the technique should always be prepared to capture the actor’s inspiration, and that this can arise in the most unforeseen moment or circumstance. Whatever the form of this wait might be, it produces a tension, and out of something as simple as this, the most refined staging emerges, because it is latent. Rather, to make the actor wait is to turn him into an ‘accessory’, into an ‘ambulant receptacle of the production team’, as in theater so often the actor is only a receptacle of the word. The actor is not a ‘spot’ in the image, nor another shape, is the emotion that derives from a dramaturgy: the dramaturgy of his presence. The moving image is not fetishist; it is moral, substantial, because of time, an element that only the actor can make visible for us. Each of his gestures has an effect, it already has it when the gesture is taking place, and only the face of the actor gathers it.

***

All movies should come to life only on the screen. Nothing of what we see should have happened in reality before. Only the camera should be able to record what is essential to the actor; People in the shooting should not be able to perceive it. This is why, increasingly, I have got used not to observe what is happening on set while shooting. Each scene should be new, with new dialogues, new turning points, and if it has already been contemplated, it becomes old and wasted. It cannot even be thought, nor conceived in a physical sense. The scene only exists in the face of the actor, and his spontaneous reaction is our gaze as spectators. What is the difference in our mind, between a “magical” Saturday night party and another trivial one? They are incomparable. Nevertheless, it is the same people, the same space, the same action. Plastically they are very similar. But the difference in intensity in the effect that they exert on us is unquestionable. Only the camera can capture this difference without interpreting it.

***

As Manny Farber says, the actor cannot be ‘alive’ as a character and preserve at the same time the style of the film. He himself is the style. He makes the symbiosis with the decor, the rhythm, the color. But he offers no significance. What does a gesture mean? A glimpse? Nothing. Gerardo Diego once read out loud one of his creationists poems, someone asked him what he pretended to say with those verses, and he answered: “I wanted to say what I said, because if I had wanted to say something else, I would have said it”. The gesture of an actor, his look, signifies themselves. The great actor does not represent, not even expresses; he only is. Perhaps his gestures work as an epiphany of the kinetic life, of the emphatic gesture and the poetic spoken word: they offer, as a presence and as a present, the afterlife of reality. But nothing more. Only great actors, as great poems, stand the weight of being only signifiers without rending. Only great directors (Bene, Warhol, Straub) have the discipline to repress their own indiscretion, and to accept each actor as a celebration.

***

The most embarrassing effect of not accepting the dramaturgy of presence as the essential aim of every actor, his immanence, and instead, to look for the certificate of their existence as character in their effects (the dramaturgy of action), is the emergence of ‘psychology’, and even what is more grievous, to make it quantifiable: Tears are shed, sweats, saliva, semen… mathematically, the more the quantity of matter, more veracity and, therefore, more profitability (a tangible good is given to the spectator in return for their money). The actor becomes the character in a quantifiable way and, therefore, controllable. Or what is the same from an emotional point of view: the presence of the actor is better valued when confronted to his own absence (staging). And besides, as Barthes pointed, this ‘combustion’ (BARTHES, 2009: 94) of the actor is decorated with spiritualistic justifications: the actor gives himself over to the demon of representation, ‘he sacrifices himself, allows himself to be eaten up from inside by his role: his generosity, the gift of his body to art, his physical labor are worthy of pity and admiration’ (BARTHES, 2009: 94). The evidence of his labor is irrefutable. And he becomes the style: the style is a bourgeois evasion towards the deep mystery of a pure presence Our Lady of the Turks. (Nostra Signora dei Truchi, Carmelo Bene, 1968).

***

Manny Farber despises the kind of interpretation of Jeanne Moreau in Jules and Jim [Jules et Jim, François Truffaut, 1961] and The Trial [Orson Welles, 1962], but yet in 1966 he had not seen an even more unfortunate interpretation: her presence in The Inmortal History (Histoire immortelle, Orson Welles, 1968) is so trivial, that her figure seems to be painted in a bad-glued wallpaper. Because the core of every cinematographic performance, according to Farber, is the suggestive material that surrounds the borders of each role, and never its psychological-ontological center: ‘quirks of physiognomy, private thoughts of the actor about himself, misalliances where the body isn’t delineating the role, but is running on a tangent to it.’ (FARBER, 2009: 588). As well in the progressive refinement of my method, and only trough the practical experience without considering the theoretical readings, I discarded the possibility that the center of a role, that is to say, the deep projection of a character, could have any esthetic validity. (‘I am only interested on the air over the actor’s head, never on what is inside, and therefore it is useless to stare at what is happening while shooting’, I declared once). Honestly, and I think this is the base of my infallible method to direct actors, I consider a sacrilege to put my gaze over a pure performance by the risk of spoiling it. I trust the camera to capture their most far profiles. And, above all, due to my Olympic contempt for cinema as an art form, it does not interest me at all what I am doing.

ABSTRACT

Based on The decline of the actor (1957) and other writings of Manny Farber, the filmmaker Albert Serra reflects on different models of interpretation and his own method of filming actors in this paper. Confronting the mechanic purity of Keaton or Laurel and Hardy, to the progressive intellectualization of Chaplin, Serra points out that an actor should offer no significance, but be the emotion that derives out of the dramaturgy of its presence, as results form films by Warhol, Carmelo Bene o Jean Marie Straub. In accordance with Farber, he comments that the actor cannot be “alive” as a character and simultaneously preserve the style of the film. He himself is the style. He makes the symbiosis with the decor, the rhythm, the color. This is why the actor should avoid the emergence of psychology. Thus, Serra explains that his decision to shoot in digital obeys to the fact that it is a more simple format to serve the actors as a performer, and that his method comes down to the principle that the technique should always be prepared to capture the actor’s inspiration, and that this can arise in the most unforeseen moment or circumstance. Whatever the form of this wait might be, it produces a tension, and out of something as simple as this, the most refined staging emerges, because it is latent.

KEYWORDS

Decline of the actor, Manny Farber, actor as performer, shooting method, Dramaturgy of presence, psychology of the actor, film style, Barthes, Warhol, Chaplin.

BIBLIIOGRAPHY

BARTHES, Roland (2009). Mitologías. Madrid. Siglo XXI Editores.

COLACELLO, Bob (2014). Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up. Vintage Books.

FARBER, Manny (1998). Negative Space. Manny Farber on the Movies. New York. Da Capo Press.

FARBER, Manny (2009). Cartooned Hip Acting. Polito, Robert (ed.), Farber on Film. The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber. New York. The Library of America.

ALBERT SERRA

Filmmaker and Producer. His feature films include, Honor de cavalleria (2006), El cant dels ocells (2008) and Història de la meva mort (2013), Golden Leopard in Locarno Film Festival. He is also Author of Els tres porquets in Kassel’s Documenta 13 (2012), and has participated in the exhibition The Complete Letters (CCCB) with the movie El senyor ha fet en mi meravelles (2011). In 2010 he collaborated with MACBA, with the project ¿Estáis listos para la televisión?, making the miniseries Els noms de Crist (2010).

Nº 4 MANNY FARBER: SYSTEMS OF MOVEMENT

Editorial

Gonzalo de Lucas

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEW

The Law of the Frame

Jean-Pierre Gorin & Kent Jones

DOCUMENTS. 4 ARTICLES BY FARBER

The Gimp

Manny Farber

Ozu's Films

Manny Farber

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Manny Farber & Patricia Patterson

Nearer My Agee to Thee (1965)

Manny Farber

DOCUMENTS. INTRODUCTIONS TO MANNY FARBER

Introduction to 'White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art and Other Writings on Film'

José Luis Guarner

Termite Makes Right. The Subterranean Criticism of Manny Farber

Jim Hoberman

Preface to 'Negative Space'

Robert Walsh

Other Roads, Other Tracks

Robert Polito

The Filmic Space According to Farber

Patrice Rollet

ARTICLES

Hybrid: Our Lives Together

Robert Walsh

The Dramaturgy of Presence

Albert Serra

The Kind Liar. Some Issues Around Film Criticism Based on the Case Farber/Agee/Schefer

Murielle Joudet

The Termites of Farber: The Image on the Limits of the Craft

Carolina Sourdis

Popcorn and Godard: The Film Criticism of Manny Farber

Andrew Dickos

REVIEW

Coral Cruz. Imágenes narradas. Cómo hacer visible lo invisible en un guión de cine.

Clara Roquet