‘ONE MUST AT LEAST BEGIN WITH THE BODY FEELING’: DANCE AS FILMMAKING IN MAYA DEREN’S CHOREOCINEMA

Elinor Cleghorn

FORWARD

FORWARD

" in: Cinema Comparat/ive Cinema, n.8, 2016, pp. 36-42

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

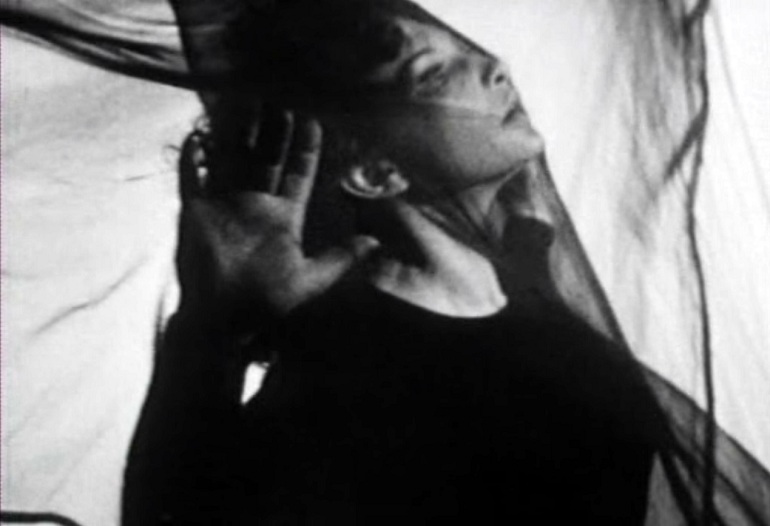

In the first scene of her film-dance Ritual in Transfigured Time (1945/6), Maya Deren appears, leaning against a doorframe. She crosses the threshold, takes up a chair, and begins to unwind a skein of wool. The film’s protagonist, played by dancer Rita Christiani, enters the frame and with her arm raised moves towards the room occupied by ‘Maya’ as if compelled to do so. The camera follows Christiani’s approaching hand while Maya, the skein held in a taut diagonal across her body, nods towards a ball of wool placed upon an opposite seat. Christiani sits down and the two women, watched over by an austere muse played by diarist and writer Anaïs Nin, commence the ritual that will bind them as doubles in the protagonist’s dance through the strictures of social obligation towards the expansive freedom of subjectivity. With the skein wrapped about her hands and her palms open, Maya mouths a silent conversation, her head swaying. While Christiani’s action of winding is executed at a naturalistic pace, successive shots of Maya unravel in slow motion. Achieved by intercutting profile shots of Christiani filmed at a consistent speed of 24 frames a second and Maya at increased frame rates, the sequence proposes the simultaneity of two different orders of time: the effect is akin to a sudden discordance in a musical phrase, like a bitonal clash. Camera motor manipulation transforms the sweeping gestures of Maya’s arms into the stuttering articulations of a puppet; her facial expressions contort, and her mouth movements evoke unheard incantations. As the sequence draws to a climax, Maya unravels the skein completely; captured at 148 frames a second, her hand gestures converge into a dance of uncanny grace and her hair clouds about her face, ‘moving slowly in the lifted, horizontal shape possible only to rapid tempos’ (DEREN, 1946a:48). Freed of the skein, her eyes closed, Maya raises her hands as her head tips back, and for about ten seconds the screen is given over to an ecstatic portrait of Maya Deren, trembling at the edges of motion.

Maya Deren performed in three of her six completed films; Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), At Land (1944), and Ritual in Transfigured Time. In her shooting scripts and pre-productions notes she refers to her roles as ‘Maya’ or simply ‘girl’ or ‘woman’, and in her theoretical writings she distances her discussion of the films from the question of her presence as an actor. Deren’s work, however, is synonymous with the enmeshment of her ‘self’ within the films themselves. In Meshes, Maya exists everywhere at once, fractured into four iterations of the protagonist’s subconscious as she dreams through a disorienting poetics of domestic containment. In At Land, shards of Maya are gathered together in the protagonist’s mythological quest to preserve a ‘constant identity’ amidst the volatile fluidity of the external world (DEREN, 1988:365 original de 1946b). In Ritual in Transfigured Time, Maya appears as the protagonist’s counterpart, at once a double of Christiani and her familiar spirit, in a social choreography that moves towards the accomplishment of the protagonist’s ‘critical metamorphosis.’ (DEREN, 2005:225, original de 1946c)

Deren came to filmmaking with a ‘very deep feeling…for dance’ (DEREN, 1984:431, original de 1941). While she never undertook formal training, she identified as a dancer; but rather than pursuing a career as a performer she made her fascination with dance as cultural expression the focus of her progression as a writer and researcher. In 1941, Deren approached choreographer and anthropologist Katherine Dunham to propose that they collaborate on book for children explaining the origin and meaning of dances ‘in a simple, anthropological way’ through illustrations and poetic text (Ibid.). Later that year Deren was employed as Dunham’s secretary and editorial assistant, and she joined her company, the first self-sustained African-American and Afro-Caribbean dance group in the U.S., on their national tour of the musical Cabin in the Sky. Throughout the 1930s Dunham carried out field work studies of Caribbean dance forms, particularly those specific to Trinidad and Haiti, and thus Deren had access to her extensive research materials, which included 16mm footage of dances performed in religious and communal ritual contexts. When her position with Dunham ended in 1942, Deren focused on her own academic study of ritual dance forms, and later that year she published an essay titled ‘Religious Possession in Dancing’ in the journal Educational Dance. Deren had not yet conceived of making films, but the essay introduces an organization of thinking around the somatic conditions and psychological effects of ritual dance and ceremonial possession that permeated Deren’s optic from the beginning. For Deren, ritual dance affected an exemplary condition of ‘depersonalization’, in which the participant, propelled through into possession by physical endurance and with the cooperation of the community, is freed ‘from the specializations and confines of personality.’ (DEREN, 1946a:20)

Deren’s choreographic direction of bodily movement in her films, including those in which she appears, draws upon the language of dance in order to absolve the personal dimension and refute characterization. Dance in Deren’s filmmaking is never merely decoration or flourish: rather, dance unfolds as a corporeal articulation of human subjectivity released from the codified social and cultural margins that determine individual identity. Dance also issues forth a transformative force: the body embodies and structures the passage of time, strives beyond muscular and gravitational limitations, and extends animate impulses to spaces and objects. The possessed body presented Deren with a model for a particular condition of filmic dance because, in the ritual context, the devotee is the instrument of collective expression residing beyond the will of the individual: dance, initiated by the participant’s somatic and psychological investment in the ceremony, is then mediated and sustained by extrinsic forces, the rhythms of drum and song, which not only act upon the dancing body but inhabit its very pulse. In Deren’s filmmaking, dance derives from the camera and its mechanistic manipulations, from the technicity that she enfolds into her screen bodies in order to affect, as she put it, a ‘transcendence’ of the ‘intentions and movements of individual performers’ (DEREN, 2005:227, originally from 1946c) In her discussion of a sequence in Ritual in which the gestures and greetings of guests at a cocktail party are choreographed into a frenetic dance of social animation, Ute Holl writes; ‘A dance appears on screen that has never been danced, that instead has been created by camera and editing work. Emotions are…produced by technical devices. They are engendered beyond the intentions of the actors’ (HOLL, 2001:165). When Deren ‘acted’ in her films, she inhabited filmic space as an embodied articulation of her own choreographic vision. She moves as an instrumental dancer, transposing the patterning described in her shooting scripts into motion, designating the attentions of her body towards her own transformation into a choreo-filmic entity.

As a dancer, Deren had an innate ability to compose her body in her filmic performances, to accomplish textures of meaning through a simple step, a raise of the hand, or a blink. In her movements she transforms exertion into uncanny grace. In At Land she twists her torso with ponderous precision as she climbs the wooded stump of a tree; she crawls across a banqueting table as if swimming, full-bodied yet somehow weightless. Meshes progresses along the rhythm of her strides; her arm extensions are controlled and balletic, her limbs slink across the surfaces of walls and corridors. When Deren began experimenting with filmmaking, she handled the Bolex as an extension of her body, as a curious prosthesis. As she writes of the tentative beginnings of Meshes; ‘I started out thinking in terms of a subjective camera, one that would show only what I could see by myself without the aid of mirrors and which would move through the house as if it were a pair of eyes…’ (DEREN, 2005:203, originally from 1946) Deren’s first filmic material was her own body, and while Meshes largely abandons the subjective perspective, the protagonist’s movements extend from Deren’s embodied intimacy with the camera, from her willingness to be moved by it, to submit to its manipulations. Later Deren conceptualized the camera as an ‘active participant’ in the creation of her filmic dances: not only could the camera extract qualities of dance through the repetitions, expansions, accelerations and attenuations its mechanism could bring to movement, but its flexibility, as a hand-held instrument, enabled the movements of the filmmaker to be incorporated into the film, to become the muscular derivation of motion within the frame (DEREN, 2005:172-173, original de 1960). Filmmaking, for Deren, was dance: a labor striving to be unburdened, an exhibition of effort releasing from weight. Deren’s roles in Meshes, At Land and Ritual constitute a complex imbrication of physical performance, choreographic direction, and embodied filmmaking. In the finale of the wool-winding scene in Ritual ‘Maya’ is overtaken by the exquisite exhaustion of the delineation of her movements into slower and slower motion. Here, Maya’s body performs a referential inversion of the work of Deren’s filmmaking.

The wool-winding sequence instigates the process of possession that draws the film into its fantastical temporal order, and as Maya is being possessed within the film, she exhibits Deren’s mechanistic and material possession of the film. As the skein unravels completely and Maya vanishes into the ball of wool, one is reminded of the metamorphosis that befalls Ovid’s Arachne, whose skilled grace at winding, weaving, and working wool condemns her body to the form of her labors, as if a spider: ‘from that belly, yet she spins her thread’ (OVID in INNES (transl.), 1955:138). While she was making her final completed film, the technically and choreographically ambitious astral ballet The Very Eye of Night, Deren described herself as a spider, spinning the project out of her own guts (DEREN, 1953). But in Ritual, Deren’s mythological vision, ‘Maya’ escapes the containments of domesticity to dance into the formless depths of the ocean, where she melds with Christiani’s protagonist, her labors transfigured into the pure cinematic substance of the negative image. In Meshes, At Land and Ritual, Maya dances conditions of female corporeality that mythologize a woman’s struggle to relate herself to herself, unmoored from the modes of societal and sexual identification that attempt to contain her. In turn, it is through these dances that Deren makes visible the work of her filmmaking: Maya embodies the strenuous physical, material, and mechanistic labors of an artist striving, as Millicent Hodson writes, to create ‘with every step an iconography of female experience’ (HODSON, 1984:xi).

In her book A Politics of Love: The Cinema of Sally Potter, Sophie Mayer discusses Potter’s ‘incorporation of dance into film’ in her 1979 experimental narrative film Thriller, a re-imagining of Puccini’s 1896 opera La Bohème. Potter trained as a dancer and choreographer from 1971, first at the London School of Contemporary Dance, where she studied with Richard Alston and Siobhan Davies, before forming the performance duo Limited Dance Company in 1974 with dance artist and choreographer Jacky Lansley. As Mayer argues, Potter’s emphasis on dance and dancing bodies in her films, including in The Gold Diggers (1983) and The Tango Lesson (1997), is predicated upon a concern with making visible the artistic labor of filmmaking: ‘Dance is not the ahistorical perfection of ballet or the mass production chorus line of Busby Berkeley films, but an individual’s work on herself, through the repetitive, difficult process of rehearsal and failure required to produce creative expression’ (MAYER, 2009:45). In The Tango Lesson, Potter herself plays the role of Sally, a filmmaker whose fascination with learning tango leads her to offer a dancer, Pablo, a role in her film in exchange for teaching her to dance. For Mayer, the value Potter places on the strenuous, exhaustive effort inscribed in performance as a labor of the body obviates identification with ‘star performers because of their celebrity’: rather, the visibility of labor connects Potter’s viewers to her performers’ ‘private selves’, expressed through the ‘discipline of performance’ (MAYER, 2009:75). In Deren’s filmmaking, the cinematic incorporation of her dancing body into the very warp-and-weave of the films makes visible, and as Mayer puts it, valuable, the physical, material, and mechanistic labors of her art making, thus conjuring a locus for the formation of Deren’s artistic subjectivity that exempts her the reduction of her ‘bodily appearance’ to an emblem of her ‘star construction’ (Ibid). Like Potter’s filmmaking, Deren’s innovations in filmic dance evolved through an intense attendance to what it meant to work, and through working, to move. In 1955, while she was making The Very Eye of Night, Deren wished to withdraw Meshes from circulation because she considered it represented the ‘virtually unintelligible’ expressions of a medium that was now her ‘mother tongue’ (DEREN, 2005:191, originally from 1965). Yet she locates a profound point of departure in a sequence that she refers to as the ‘four strides.’

Holding a knife, one of the dreaming ‘Mayas’ begins to move towards another Maya, sleeping on a chair. She rises and begins to stride; in close-up her sandaled foot lands first on sand, on grass in the next frame, then on to pavement, and finally on to a rug1. The sequence culminates with the knife-bearing Maya returned to the room, advancing upon the sleeping Maya. Deren choreographed the ‘four strides’ with the intention to convey the implicit violence of an individual’s psychological journey; as she writes, ‘What I meant when I planned that scene is that you have to come a long way –from the beginning of time– to kill yourself…’ (Ibid, 192). Writing in 1955, in a letter to James Card, curator of moving image at George Eastman House, Deren describes the illuminating impact of witnessing the embodied work of her own filmmaking in Meshes. In the four strides sequence, in which this work makes itself visible as seam, as suture, Deren identified the emergence of one of the most fundamental principles of her choreographic filmmaking; the dynamic continuation of bodily movement across oneiric dislocations in time and space. This ‘short sequence’, she writes, struck her ‘ like a crack letting the light of another world gleam through…’ in the metaphorical closed room of Meshes of the Afternoon. Deren writes:

…as I used to sit there and watch (Meshes) when it was projected for friends in those early days… I kept saying to myself “The walls of this room are solid except right there…There’s a door there leading to something. I’ve got to get it open because through there I can go through to someplace instead of leaving here by the same place I came in.”

And so I did, prying until my fingers were bleeding. And so came to a world where the identity of movement spans and transcends all time and space… (Ibid) .

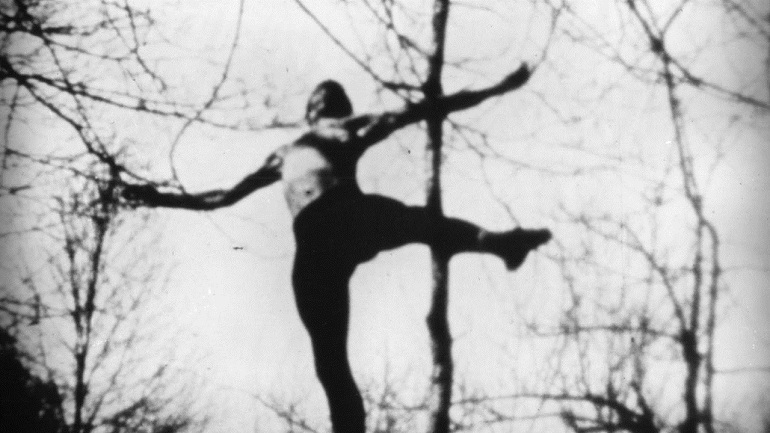

Meshes was not a dance film per se, but rather, as Deren put it, a ‘choreography in space’, in which dance derives from the protagonist’s naturalistic movements across ‘a world of imagination’ (DEREN, 2005:221, original de 1945) described by the film’s shifting spatiotemporal propositions. When she began to explore the possibility of creating a dance ‘expressly for camera’ (DEREN, 2009: 262, original de 1945) in 1945, the ‘four strides’ sequence, which she performed, choreographed, and edited, yielded a radical approach to the treatment of the dancing body on film, described by dance critic John Martin as ‘…the beginnings of a virtually new art of “choreocinema” in which the dance and the camera collaborate on the creation of a single work of art’ (MARTIN en DEREN, 1988:366, originally from 1946). Following the making of At Land, and propelled by her interest in ritual dance and by the unique choreographic capacities of the camera’s movements and mechanisms, Deren made A Study in Choreography for Camera, ‘a dance so related to camera and cutting that it cannot be “performed” as a unit anywhere but in this particular film’ (DEREN, 2005:222, original de 1945). Made in collaboration with Talley Beatty, a dancer Deren met whilst working with Dunham, Study presents a solo dancing body traversing across an expansive, symbolic geography. Deren described the film as a ‘sample of film-dance’, and she hoped it would usher in ‘a new era of collaboration between dancers and filmmakers…one in which both would pool their creative and talents towards an integrated art expression’ (Ibid). While Deren does not actually appear on screen she is almost overwhelmingly present as the agent of the film’s choreographic innovations, as director of Beatty’s movements, and as the muscular propulsion for the mechanistic enhancement of his pro-filmic performance. Deren’s choreocinematic conceit, predicated upon the embodied inscription of the work of her filmmaking into the movements of the screen body, was particularly influential for women artists transitioning to filmmaking from dance, such as the experimental filmmaker and documentarian Shirley Clarke, and the film and video artist and purveyor of cine-dance Amy Greenfield. Writing in 2002, Greenfield discusses the ways in which Study ‘redefined the possibilities for the transformation of dance into avant-garde film’ (GREENFIELD, 2002:21). Greenfield describes the climactic movement in Study, the ‘idealized, floating leap’ (DEREN, 2005:224, originally from 1945) in which Beatty makes an unhindered ascent sustained for almost thirty seconds, as Deren’s leap. Achieved by cutting together separately filmed fragments of footage of Beatty as he rises, plateaus and descends, the leap appears to release the dancer from the pull of gravity, conjuring an instance of dance entirely specific to Deren’s filmic manipulations.

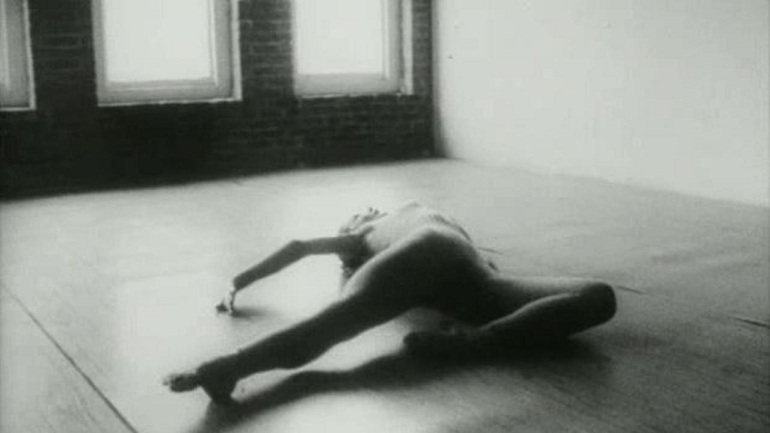

Greenfield came to filmmaking in 1970 after ten years training as a dancer and choreographer, and her cine-dance is predicated upon the enmeshment of her own performances in front of the camera, her choreographic direction of movement behind the camera, embodied cinematographic negotiations of space, and intricate processes of editing. In Element, made in 1973, Greenfield struggles naked through mud, her limbs rhythmically emerging and submerging as the camera dances across her body. Element was filmed by Hilary Harris, an experimental and documentary filmmaker who made his own dance-film, Nine Variations on a Dance Theme, in 1966.

Greenfield directed Harris’ camerawork to alternately synchronize with and oppose the intense language of her movements, activating the camera’s volatile collusion in the communication of a uniquely cinematic ‘female-human-experience’ (GREENFIELD en HALLER, 2007:159). For Greenfield, Deren’s emphasis on embodied camerawork as the derivation of the motile energies of dance, as conceptualized in her writings following the making of Study, was profoundly influential on her own transition from dance and choreography into experimental filmmaking. As she writes, ‘Deren wrote of the incalculable and uncategorizable kinds of movements possible with the handheld camera in direct relationship to the body. This became the hallmark of my use of the camera’ (GREENFIELD, 2002:26). Deren similarly influenced Clarke, who made her first film Dance in the Sun in 1953 after studying with Martha Graham, Hanya Holm and Doris Humphrey, in her creation of cine-dance in choreographic collaboration with the camera. Clarke made Dance on a Bolex she received as a wedding present: the film features choreographer and dance artist Daniel Nagrin performing ‘fluid movements intercut between an interior and exterior location’ (RABINOVITZ, 1991:97). After meeting Deren and viewing her works in 1953, Clarke was particularly inspired by the choreographic principles of Ritual, and in films including In Paris Parks (1954) and Bridges-go-round (1958) she extends cine-dance beyond the dancing body, to the inherent rhythms of everyday activities and the pace of urban spaces.

Maya Deren was by no means the first female artist to explore the relation of dance and film, but she stands out as the most illuminating cynosure within this historical nexus. Throughout the earliest decades of cinema’s ‘experimental mode’, a number of pioneering women artists sought alliances between film and dance. Film scholar Antonia Lant has suggested that women tended to ‘gravitate’ towards dance in part because the form encompassed a particular attunement to embodied experience (LANT, 2006:145). For artists exploring the relation of film and dance before Deren’s inauguration of choreocinema in the 1940s, certainly an intuitive impulse towards dance was foundational to the creation of radical constitutions of film art. The technological, conceptual, and aesthetic innovations of Loïe Fuller, Germaine Dulac, Lotte Reiniger, Mary Ellen Bute, Stella Simon, and Sara Kathryn Arledge, for example, undoubtedly extended from each artist’s embodied relationship to dance and choreographic movement, either through performance, choreography, or spectatorship. However, the diverse and complex motile, temporal, sensorial and perceptual conditions that have arisen from each of these artists’ unique confluences of dance and film completely challenge restrictions of ‘film-dance’ to the normative margins of a gendered sensibility. Furthermore, an examination of the contributions of these artists through the lens of their closely held ‘feelings’ for dance enables a critical recuperation of their personal motivations, which thus necessitates a discursive prioritization of individual subjectivity and creative agency. For each of the artists mentioned, dance was not merely a representational subject or a stylization of movement. Rather, dance functioned as the presiding impetus structuring their works’ propositions of time, space, and movement, which in turn arose from their respective conceptualizations of filmmaking, at the material level of production, as intentionally choreographic operations. Deren’s choreocinema introduced the concept of filmmaking as dance, as a creative union of bodily performance, choreographic patterning, and technical manipulation predicated upon the foregrounding of female artistic agency. As Maria Pramaggiore has shown, Deren’s ‘self-representation’ films –Meshes, At Land and Ritual– resist ‘cultural imperatives surrounding gender and sexuality’, and as such envisage female ‘…desire and identification as…a fluid discovery rather than as certitude’ (PRAMAGGIORE, 2001:240). In turn, it is the work of Deren’s filmmaking, the strenuous physical, material, and mechanistic labors of an artist striving against the reductive margins female identification is too often contained within, which is activated in the films in which she appears. As Pramaggiore writes, Deren’s filmmaking ‘…(treats) the dialectics of individual identity as a limiting choreography’ (Ibid, 239): by composing her films in adherence with the logics of ritual, Deren created a model through which to ‘defamiliarize and circumvent’ (Ibid) such limitations. In Deren’s films, dance derives from the application of the unique capacities of the medium to the originary performances of her screen bodies, which converge in choreographic complexes that locate meaning as always made in movement. When she appears on screen, the identity of Maya Deren is indeed defamilarized, but through the fragmentations, multiplications, accelerations and attenuations to which she subjects her own body, ‘Maya’ is conjured as the choreographic projection of Deren’s ‘conscious manipulations’ (DEREN, 1946a:20), which combine to describe female subjectivity and feminist artistic agency as indeterminate, interstitial and always in motion, always in formation.

FOOTNOTES

1 / Although Deren described this as the ‘four strides’ sequence, there are actually five close-ups of her foot, the first two landing onto sand.

ABSTRACT

For the Ukrainian-American experimental filmmaker Maya Deren (1917-1961) filmmaking was dance. Through her own presence as actor, her technical and mechanistic manipulations of performed movement into dance, and her embodied dance-like engagements with filmic technicity, Deren innovated a radical approach to the making of dance-film, which was heralded in the mid-1940s as ‘a virtually new art of “choreocinema.”’ This essay explores the ways in which Deren’s ‘choreocinema’ derived from her long-held feeling for dance, and argues that her acting roles in Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), At Land (1944) and Ritual in Transfigured Time (1945/46) constitute complex choreographic imbrications of performance, direction, and filmmaking. While Deren’s filmmaking is synonymous with the enmeshment of her ‘self’ within the films themselves, her performances are predicated upon her immersion in dance as a refutation of the personal dimension. Through examination of the impact of Deren’s interest in dance as ritual, collective, and depersonalized expression, this essay argues that Deren’s acting roles exemplify her ambition to utilize dance, created by the manipulations of the filmic instrument, to articulate female subjectivity released from the margins of normative social and cultural codifications. In turn, this essay looks towards the resonance of Deren’s innovations through the work of dance-filmmakers including Shirley Clarke, Amy Greenfield and Sally Potter, proposing that a particular attunement to dance has, for feminist filmmakers, enabled ‘choreocinema’ to evolve in the form of nuanced meditations upon embodied labor, artistic agency, and the ever-motile configuration of female subjectivity.

KEYWORDS

Maya Deren; choreocinema; dance; dance-film; feminism; subjectivity; performance; embodiment; labor; ritual.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

DEREN, Maya (1941). Letter to Katherine Dunham. MELTON, Hollis (ed.) (1984). The Legend of Maya Deren: Vol 1, Part 1 ‘Signatures.’.New York: Anthology Film Archives/Film Culture.

DEREN, Maya (1945). Correspondence with Sawyer Falk. MELTON, Hollis (ed.) (1988). The Legend of Maya Deren: Vol 1, Part 2 Chambers. New York: Anthology Film Archives/Film Culture.

DEREN, Maya (1945). Choreography for Camera. Dance Magazine, October, in MCPHERSON, Bruce R. (Ed.) (2005). Essential Deren: Critical Writings on Film by Maya Deren. Kingston, NY: Documentext.

DEREN, Maya (1946a). An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form, and Film. New York.The Alicat Bookshop Press.

DEREN, Maya (1946b). ‘Three Abandoned Films’, screening program notes. MELTON, Hollis (ed.) (1988). VèVè Clark, Millicent Hodson & Catrina Neiman The Legend of Maya Deren: Vol 1, Part 2 ‘Chambers’. New York: Anthology Film Archives/Film Culture.

DEREN, Maya (1946c). Ritual in Transfigured Time. Dance Magazine, Octubre, en MCPHERSON, Bruce R. (Ed.) (2005). Essential Deren: Critical Writings on Film by Maya Deren. Kingston, NY: Documentext.

DEREN, Maya (1953). Letter to Gene Baro. Inèdita. Maya Deren collection. Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Centre at Boston University.

DEREN, Maya (1960). Adventures in Creative Film-Making. Home Movie Making. MCPHERSON, Bruce R. (Ed.) (2005). Essential Deren: Critical Writings on Film by Maya Deren. Kingston, NY: Documentext.

DEREN, Maya (1965). 'A Letter’ (to James Card). Film Culture, no.39. MCPHERSON, Bruce R. (Ed.) (2005). Essential Deren: Critical Writings on Film by Maya Deren. Kingston, NY: Documentext.

GREENFIELD, Amy (2002). The Kinesthetics of Avant-Garde Dance Film: Deren and Harris. MITOMA, Judy (ed.), Envisioning Dance on Film and Video. London & New York: Routledge.

HALLER, Robert A. (2007). Amy Greenfield: Film, Dynamic Movement, and Transformation. BLAETZ, Robin (ed.), Women’s Experimental Filmmaking, (ed.). Durham & London: Duke University Press.

HOLL, Ute (2001). Moving the Dancer’s Souls. Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde. NICHOLS, Bill (ed.). Berkeley & London: University of California Press.

HODSON, Millicent (1988). MELTON, Hollis (ed.) (1984). The Legend of Maya Deren: Vol 1, Part 1 ‘Signatures.’.New York: Anthology Film Archives/Film Culture.

LANT, Antonia (2006). What was Cinema? (Introduction). LANT, Antonia, PERIZ, Ingrid (eds.). The Red Velvet Seat: Women’s Writing on the First Fifty Years of Cinema. London & New York: Verso.

MAYER, Sophie (2009). A Politics of Love: The Cinema of Sally Potter. London. Wallflower Press.

PRAMAGGIORE, Maria (2001). Seeing Double(s): Reading Deren Bisexually. NICHOLS, Bill (ed.). Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde. Berkeley & London: University of California Press.

OVIDIO (150). The Story of Arachne. Metamorphoses. Book VI. INNES, Mary (trans.) (1955). London. Penguin.

RABINOVITZ, Lauren (1991). Points of Resistance: Women, Power & Politics in the New York Avant-garde Cinema, 1943-71. Urbana & Chicago. University of Illinois Press.

ELINOR CLEGHORN

Elinor Cleghorn is a writer, researcher, lecturer and film programmer specializing in early feminist filmmaking and theories of embodiment. She received her PhD from Birkbeck College, University of London, in 2012 with a thesis exploring the embodied filmmaking of Maya Deren, Lotte Reiniger and Loïe Fuller. In 2011, Cleghorn curated Maya Deren: 50 Years On, a dedicated program of screenings, discussions and events commemorating the 50-year anniversary of the filmmaker’s death, at the British Film Institute in London. She has given invited talks on Deren’s filmmaking at Nottingham Contemporary, BFI Southbank, Camden Arts Center, and Tate Modern, and participated in a variety of symposia and research events on feminist filmmaking at venues including ICA London, BFI, Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, and the London Feminist Film Festival. Her writing has appeared in Screen, The Moving Image Review and Art Journal, LUX Online, and The International Journal of Screendance.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Nº 8 PORTRAIT AS AN ACTRESS, SELF-PORTRAIT AS A FILMMAKER

Editorial. Portrait as an actress, self-portrait as a filmmaker

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

About the femenine

Maya Deren

About Fuses

Carolee Schneemann

Conversation about Wanda by Barbara Loden

Marguerite Duras and Elia Kazan

About the Film-Diary

Anne-Charlotte Robertson

Nothing to say

Chantal Akerman

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

About the Women Film Pioneers Project

Alejandra Rosenberg

Medeas. Interview with María Ruido

Palma Lombardo

VIDEO ESSAY

Florencia Aliberti, Caterina Cuadros and Gala Hernández

ARTICLES

Lois Weber: the female thinking in movementWeber: the female thinking in movement

Núria Bou

‘One must at least begin with the body feeling’: Dance as filmmaking in Maya Deren’s choreocinema

Elinor Cleghorn

Nothing of the Sort: Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970)

Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin

The Trouble with Lupino

Amelie Hastie

Presence (appearance and disappearance) of two Belgian filmmakers

Imma Merino

Identity self-portraits of a filmic gaze. From absence to (multi)presence: Duras,Akerman, Varda

Lourdes Monterrubio Ibáñez

REVIEW

Jorge Oter; Santos Zunzunegui (Eds.) José Julián Bakedano: Sin pausa / Jose Julian Bakedano: Etenik gabe

María Soliña Barreiro