ABOUT THE WOMEN FILM PIONEERS PROJECT

Alejandra Rosenberg

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

I had the pleasure to chat with Sofia Bull and Kate Saccone on a chilly morning in May in New York City regarding the Women Film Pioneers Project1. Edited by Jane Gaines and Monica Dall’Asta, WFPP is published online by Columbia University’s Center for Digital Research and Scholarship.

I met Kate at her office and together we "skyped" with Sofia, who lives in the UK (where she is a Professor in Film at Southampton University). In a small real and cyber space, the three of us represent three generations of women working for WFPP: Sofia, who has collaborated with the project since 2005 and is currently the co-editor of the Overview Essays; Kate, who started working with for the project in 2011 and is currently the Project Manager; and me, one of the new Research Assistants who entered the project nine months ago.

Alejandra Rosenberg: Just to warm up, what is the Women Film Pioneers Project?

Kate Saccone: The Women Film Pioneers Project is many different things. On the one hand, it is an online resource that advances research on female filmmakers in the silent era, who were more than actresses and who worked behind-the-scenes as directors, producers, editors, screenwriters, distributors, and more. On the other hand, it is also a community, a network, of scholars all over the world who are interested in women in early cinema.

Sofia Bull: The output of this research project is hard to define because of its digital nature: in one sense, it could be described as a data-base, in another, as an online publication.

KS: It is also a portal that points the reader in a multitude of directions through links to holdings in FIAF archives around the world –so it really simultaneously points outward while also containing original scholarship within it.

SB: We could say that it is a resource for research, while it also is a place where we publish research.

AR: I think WFPP is extremely interesting in how it plays with two temporalities by publishing research in innovative ways while researching about something that happened a century ago.

KS: Yes, I agree, and going off of that, it is also very much a part of the contemporary moment in the relationship between cinema studies and digital humanities, where there are a number of fantastic digital or online-only resources that focus on early cinema research, including Media History Digital Library2 and the Media Ecology Project3.

AR: It is also very stimulating how the Women Film Pioneers Project constructs an international community of scholars, opening and crossing the borders of national scholarship.

KS: Yes, it is so trans-national just in terms of the contributors involved and the archives that they use in their research. When you reconnect at a conference or silent film festival, there is always this really great sense of a global community.

SB: The main aim of the project is, on the one hand, to find more things about women in the silent era by doing re-historical research. However, on the other hand, one of the aims is also to foster this research community; creating a tool for activism in the present era. A way to give women in the film industry, and women scholars as well, the sense of a long running history. Everyone is so aware nowadays about how there are not enough female filmmakers, and how it is a struggle for female filmmakers today. But I think it is interesting that not that many people know that there has always been female filmmakers and that the percentages were actually comparatively high in the silent era... and that can be a source of inspiration nowadays.

AR: Usually when one talks about women filmmakers, one thinks of Agnès Varda, Maya Deren... but we tend to forget that women were also present at the birth of cinema and it is very painful to realize that we were never taught about all these women that also founded and shaped cinema, as, for instance, Alice Guy or Lois Weber.

SB: Some of these women have been known for a long time but the sort of notion that women were involved in film culture (not just in filmmaking but also owning cinemas, writing about film from a very early age...) is something that is rarely talked about. And partly it is because people didn't know about it and, actually, WFPP has been instrumental in making this information available. It is only now that people are understanding the scope of that early era. Personally, I believe it is very important to understand the scope because, otherwise, when you only have a few figures, they seem like exceptions, making it hard to see them as part of a canon; it makes them appear like rare birds, in a sense.

KS: I just re-read Jane M. Gaines’ and Monica Dall’Asta’s prologue in Doing Women’s Film History4 and I love how they highlight that we need these women today just as much as they need us now. The example they use is Elvira Giallanella, an Italian woman who directed a film that was only discovered in 2007: it didn’t get seen until recently. This transnational community of scholars in the present day needed this discovery (and others) to continue to help show that there were all these women working as directors in the silent era. At the same time, Elvira also needs us now to have the public screening of her film that she never had. It is really a wonderful dialogue between the past and the present; between filmmakers, researchers and viewers.

AR: In her research, Gaines is also very interested in the historiographical difference between ‘what has happened’ and ‘what is said to have happened’; a distinction which is engaged with activism through WFPP, as, thanks to the project, one can see that ‘what is said to have happened’ doesn’t coincide with what really happened, since all these women never made it to the discourse of history.

SB: What I really appreciate with the project is that it’s encouraging all the researchers that are involved with it to think actively and reflexively about historiography and about the process of writing history, and to not just somehow re-write history in order to create a new set of facts... We are trying to have an awareness about the complexities and difficulties in writing history, which involves the awareness of the difficulty in finding historical facts. It is not just a simple process of re-visiting history: it is a much more complex attempt on thinking about historical writing and what it means to introduce female figures into that story.

KS: In our guidelines we actually instruct contributors not to write an encyclopedia-like entry. As Sofia said, this reflexive approach is crucial. We want contributors to interrogate the research process itself as they visit archives and see what is available and what is lost in terms of archival resources (films, documents, etc.). We are very upfront about this from the beginning and very aware of the challenges and questions facing this type of historical recovery work.

AR: I guess you are hyper-conscious of being one of the producers of history and, as such, being critical of the ways in which that has been done, or is being done.

SB: Well, yes, we try not to reproduce the mistakes of others but, maybe, at the same time, we might be committing other mistakes as we might be missing on things that we don’t even know we are missing.

AR: Kate, since you mentioned the guidelines, how does the project work more specifically?

KS: Basically, we have two sections: the Career Profiles, which are short (around 1000-1500 words)…

BS: …and the Overview Essays, which are longer (between 1000 and 4000 words).

KS: The Career Profiles, which are written by established film scholars and archivists, are focused on a single individual (although sometimes a career profile has two to three pioneers featured in it, because they could be sisters who worked exclusively together, like the Ehlers sisters, who worked in Mexico and in the United States). These profiles are mainly focused on the filmmaker’s career and we don’t necessarily need all the biographical information (childhood, etc.). It also includes a bibliography, a section with relevant archival paper collections, and the filmography. This last section, the filmography, is the most important part of the Profile because we list extant films and all the archives that hold prints so that the readers have a way to find these films. We have also been trying to add more clips to the profiles, as well as DVD information when available. Also, images are very important to us and we have a mix of portraits, film stills, screenshots, and documents (like death certificates, etc.) featured in each profile, when these images are available.

SB: The Overview Essays started out by the fact that the project went global and that there was this sense that there should be some sort of text that wasn’t focused on the individual women but on the different parts of the world that these women were active in. Therefore, we were asking the scholars to write an Overview Essay in which they could discuss more generally women’s role in cinema in a certain part of the world during the silent era. Then, we thought that we could use the Overview Essays for more contextual aspects, like having Overview Essays on different kinds of professions (for instance, on female cinematographers) in which we could link in the essay to all the individual Career Profiles, creating, thus, a digital space-essay that would gather all the links together. So, quite recently, we have started extending the Overview Essay section, thinking about it as a publishing platform for more general texts and articles on women and silent cinema, focused on different themes, geographical areas... thus, we are more flexible now on the kind of texts that we publish. In other words, the Overview Essays are a different space opened up for different kind of articles, which are all now peer reviewed, working, thus, as an academic journal more than an online data-base.

KS: And just to give a scope of the types of Profiles that we have, they range from pioneers who worked in Germany, in Turkey, Egypt, former Czechoslovakia, Russia, France, United Kingdom, the Netherlands, China, Japan... the list goes on. As of today we have 214 published profiles, about 200 assigned profiles –which means they are currently being researched and written–, and over 600 unassigned names. And that is clearly not all the women that worked in the silent era... One of the things that Jane Gaines always says, and that she has made me aware of, is that although many women became famous or successful, there are a bunch of women who failed to have a film career, or who were anonymous workers in labs and offices and we will never know their names... So this is just the tip of the iceberg.

SB: That is also something that the Overview Essays try to cover: the fact that it is impossible to trace all these individual people.

AR: So there are more than a thousand names that WFPP wants to research on... What is the exact range of time that the project focuses on?

BS: Formally, we are covering from the birth of cinema to the coming of sound.

KS: Yes, but we also do make some exceptions. For instance, in some places like Latin America, China, Japan and India, sound came later, so we are a little bit more flexible depending on the region. Also, occasionally the community of scholars discovers a pioneer who we need to include, like Esther Eng, who started working later in the 1930s. However, she was this very radical, queer, independent director, producer, screenwriter and distributor, working outside of Hollywood –in San Francisco and in Hong Kong– and we felt like we had to include her in the project. But, typically, as Sofia said, our range is from the birth of cinema to the coming of sound.

BS: ...which, as Kate said, is so different from country to country, which is one of the problems that we are finding as we expand globally. For instance, some parts of the world didn’t have any women in the silent era but did have some in the early sound period. Or rather, I should say, we don’t know if there were any women working in the silent period; there might have been but they haven’t been “discovered” yet.

AR: Talking more specifically about these women, my sense is that many of them began as actresses and then started to acquire other roles behind the cameras, such as directors...

KS: Yes, many were actresses who then went on to become screenwriters and producers and directors. But many others started out as directors or screenwriters and then added acting to their resumes, or never acted at all and only worked behind the camera or in some other capacity. It’s difficult to generalize, as there are just so many ways that women worked in the early global film industry.

BS: The problem for me is that I think directors are important. However, and one of the things that I really appreciate with our project is that we try to acknowledge a big range of professions. And part of the issue of writing women out of film history is maybe this sort of auteurist tradition: if you look beyond directors, you will find so many women that were doing amazing things and that had quite a lot of influence.

KS: Yes, in college, no one ever taught me about all these women. Not only did they not teach me who Dorothy Arzner was, or who Lois Weber was, or who Alice Guy was, but they would never even cover someone like, say, Maude Adams, who worked in a totally different capacity than a director. Adams, who also was a stage actress, did research into lights and lighting technology and the end result of her research became the industry standard during the sound period. We really need to look beyond just the auteurist model to understand the full scope.

SB: Also, one of the interesting things that comes up is that there were a number of women working in collaborative relationships with male directors but that didn’t always get the credit that they should have gotten, like Alma Reville (who was married to Alfred Hitchcock).

KS: Yes, for example, there was an actress in Russia, Ol’ga Rakhmanova, who started out as an actress and then became a screenwriter. She ultimately became a director in her own right, but her first directorial “credit” was when she was on a location shoot and suddenly the director died and she stepped in to help to finish the film and is credited as co-director in one version of the film, and not credited in a later version. This lack of stable attribution is characteristic of so many women’s careers. Also, Gene Gauntier, in the United States, who was working with the director Sidney Olcott. In her memoirs, she talks about how she was essentially co-directing but she never got the credit. I know memoirs should not always be taken as absolute truth, but these personal accounts do give us more information about what credit was denied in collaborative relationships. Or Lois Weber, who while credited, co-directed many films, like Suspense, with her husband, which raises complex questions about authorship and creative control in the collaborative relationship.

AR: There seems to be something very patriarchal of the way credits are established, with a necessity of distinguishing and separating each role...

SB: Yes, that is part of the problem that we have sort of mentioned, obviously. A lot of these collaborative women who worked with men never got a formal credit and we only know that they worked on the film because there are other documents or oral accounts telling us that she was involved in a much bigger role than the one that was acknowledged. We don’t really know but there is an assumption that that would have happened more to women than to men.

AR: Do you think that the depictions of women would be different, if there were women in the crew? Or is that impossible to know?

SB: It is not necessarily the case that the films directed or written by women were more feminist in the sense that we perceive the concept today but, potentially, one would assume that there was a higher likelihood of them including female perspectives or female stories... But one of the things that is hard about this is that so many of the films are still lost and it is hard to make any sort of generalizing comment. Many of the films are not here and available so that we can actually do that. Thus, it is hard to draw conclusions of the text, or of the ideology or their meanings, in relation to the portrayal of women (although it might be more possible to do so in individual cases)… I think this question of the representation of women by women in early cinema is something that is also very important and that potentially we could be covering in the future with our Overview Essays.

AR: Is there something else that you would like to add?

SB: I think one of the things that we often talk about regarding women filmmakers is that, as the research shows, there was a flexibility of roles in that early era, particularly outside of the bigger companies. Thus, there were a lot of women who were doing many different roles: they were not just actresses and directors; they were also actresses, directors, producers, set designers, screenwriters... all at the same time and in different productions, which is something very exciting to think about.

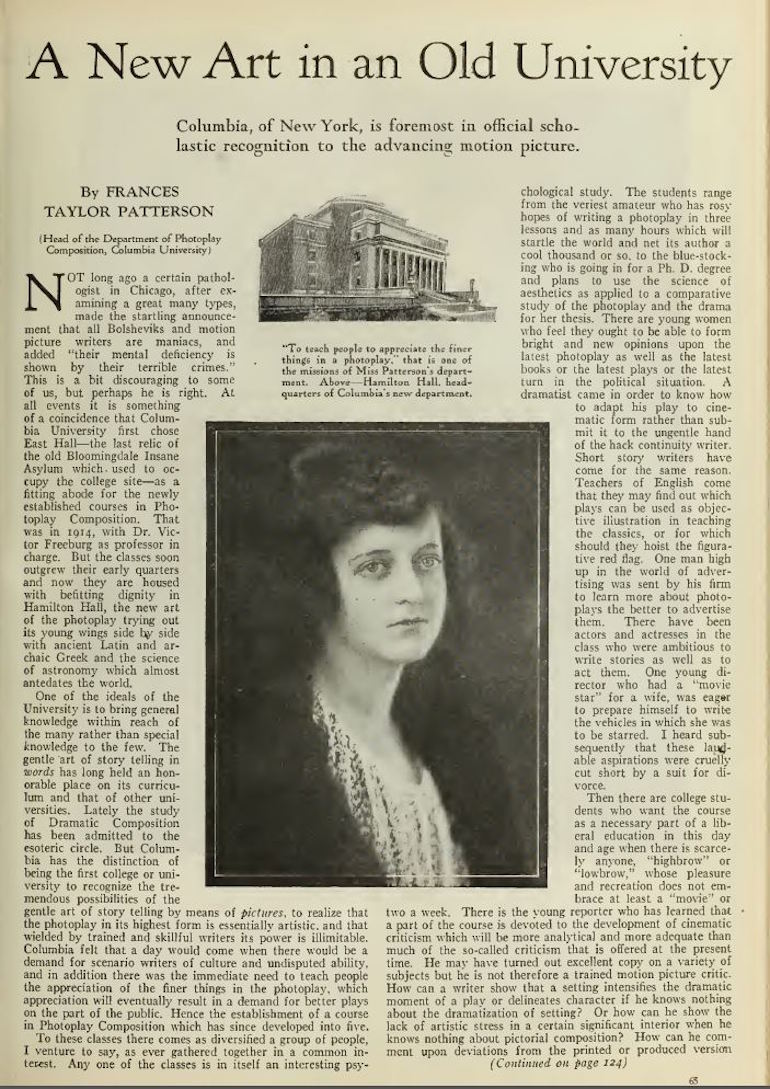

KS: Yes, this is really crucial. The Women Film Pioneers Project features a wide range of occupations and the list is always growing as we add the terms that the contributors find or that were used in that time. For example we have film critics and film scholars –one of my favorite pioneers is Frances Taylor Patterson who was one of the first university lecturers on film: she started teaching a screenwriting course in 1917 at Columbia University. Also, we feature costume designers, title designers, and titles writers, like the Swedish title-writer, Alva Lundin, who Sofia wrote an entry on for us, as well as exhibitors, projectionists... it is a very wide range of occupations. So we work with a meta-data librarian to create a taxonomy of occupations as they come in, which reminds me that I should point out that this project is produced by Columbia Libraries and Columbia’s Center for Digital Research and Scholarship, more specifically. So we work with web developers, and meta-data librarians, and specialized librarians, and computer programmers to create the digital project that you see... But, going back to the taxonomy, it’s a growing list of occupations that fosters some really fascinating discussions and raises complex questions. For example, last year we published a profile on Finnish pioneer, Jenny Strömberg, and it wasn’t clear to us if she had financed the production of a film about her hunting dogs, a film in which she also appeared. We didn’t know what to call her, and we were going back and forth with the author of the article, and with the meta-data librarian, questioning what we should call her “occupation.” We didn’t want to put “producer” because that is misleading, so we ended up putting “society matron” as her occupation, because it was her status in society that perhaps influenced the production of this film. However, the great thing about this being a digital project is that, if the contributor does more research in the future, and finds evidence of something different, we can change the information immediately. If this was a published book, which was how the project was envisioned initially, that wouldn’t be possible.

AR: One of the great things about it being digital is that it enables the project to be accessible to everybody, right? A simple search on the internet would lead you to the website, and you can start reading and getting deep into the topic.

KS: Right. Many more people find us, and access us, than if the project was a book. Also many family members and relatives of these women write to us, recognizing their grandmothers, great-aunts... and they reach out to us with information, documents, etc. creating a very nice community outside academia.

SB: We get a wide audience, which is very good. Definitely we reach many more people due to the digital nature of the project. The challenge for the project is also to come up with interesting pathways on the website for people to discover things that maybe they weren’t looking for initially. That way the reader can easily cross professions, borders… which is also one of the interesting things of the project: its global nature. Not only how we cover different national contexts but that we find many women that had international careers from quite early on, and a sort of geographical fluidity of filmmaking in the early era: women were moving around much more than we would assume.

AR: It is interesting to question how to incorporate these women into a film history class. I see cases where there is a week reserved to “women directors” but I would disagree with that approach as it is creating an exception from that type of label. Why would a week be called “women directors” if all the other weeks are not called “men directors”?

KS: Yes, it’s like if it was the specialty week!

AR: Wouldn’t it make more sense just to integrate everyone without creating the difference, so that students would learn everything without thinking that women filmmakers should be an exception?

BS: It is a very interesting question, the question on how to teach women in cinema. And, in one way, it can be good to highlight it –and a lot of people would go for that in an attempt to make it visible–, but, obviously, as you say, ideally we should be including it more organically, sort of across the board. But the issue remains: as long as female filmmakers are an exception it becomes difficult to not treat them as such... But you might have to not treat them as such to make sure they are not an exception.

KS: I was just thinking about this issue last month when the Film Society of Lincoln Center had their Queer Cinema Before Stonewall series, which featured a handful of films by our pioneers... and they were not labeled as “women films”, they were just part of the larger program, which was fantastic. And it was great to see films by Alice Guy-Blaché or Dorothy Arzner in dialogue with Vincente Minnelli and Kenneth Anger. At the same time, part of me wanted to only highlight these women’s specific screenings because their films are so rarely shown and they are so rarely a part of the conversation. It gives me hope that, due to the growing awareness of how horrible it is today for female directors, producers, screenwriters, etc., I am seeing a lot more articles, screenings, and resources available (like the Nordic Women in Film5). It is an exciting moment to see that some of these questions and issues are being raised and these discussions are being held in the public sphere.

AR: What I love about the project is that if we are able to put all these women in the discourse that we construct of history, we are enabling female students to also see themselves as directors, as they will have a larger scope of role-models to identify with, a scope not only constructed mainly by white men.

SB: Definitely. And, hopefully, the project is important for obviously re-writing that history but, also, as a source of inspiration for future filmmakers and future female scholars. In this sense, it has worked as a supportive network that allows young scholars to start publishing and to try to do some serious historical research, while also getting lots of help and lots of contacts from other women across the world. Basically, it is a very nice group of people.

KS: Exactly! It’s been great to get to know all of these wonderful scholars and their work, but also to get to know these pioneers very intimately (at least that is how I feel with every new entry, as I work closely with the author to edit, reread it, and publish it)… I feel like all of these women are very present in my life, they are very inspiring creatively, and I am very conscious of their work as I go about my life –not only do I now see my gender actively involved in cinema’s past, but these women continually challenge me today.

1 / https://wfpp.cdrs.columbia.edu/

2 / http://mediahistoryproject.org/

3 / https://sites.dartmouth.edu/mediaecology/

4 / Knight, J., Gledhill, C., eds, Doing Women’s Film History: Reframing Cinemas, Past and Future. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015.

5 / http://www.nordicwomeninfilm.com/

In this conversation, the author discusses with Sofia Bull and Kate Saccone about the Women Film Pioneer Project, which is edited by Jane Gaines and Monica Dall’Asta and published online by Columbia University’s Center for Digital Research and Scholarship. The conversation starts with general descriptions of the WFPP, that also touch on the internal methodology of the project, and is taken towards more specific discussions on the relations between cinema studies and digital humanities; women’s role and professions in the silent era; and on the importance of rethinking the hegemonic discourse of film history.

KEYWORDS

women in film, silent era, pioneers, research communities, Jane Gaines, film history, digital humanities, Alice Guy, Lois Weber, Elvira Giallanella, Dorothy Arzner, Maude Adams, Alma Reville, Gene Gauntier

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Knight, J., Gledhill, C., eds, Doing Women’s Film History: Reframing Cinemas, Past and Future. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015

ALEJANDRA ROSENBERG

Sponsored by Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Alejandra Rosenberg is an MA student at the Film Studies department of Columbia University, where she collaborates with the Women Film Pioneer Project and where she is developing a thesis under the provisory title ‘One Last Movie: Constructing our ghost through the reconstruction of our (his)stories’.

Nº 8 PORTRAIT AS AN ACTRESS, SELF-PORTRAIT AS A FILMMAKER

Editorial. Portrait as an actress, self-portrait as a filmmaker

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

About the femenine

Maya Deren

About Fuses

Carolee Schneemann

Conversation about Wanda by Barbara Loden

Marguerite Duras and Elia Kazan

About the Film-Diary

Anne-Charlotte Robertson

Nothing to say

Chantal Akerman

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

About the Women Film Pioneers Project

Alejandra Rosenberg

Medeas. Interview with María Ruido

Palma Lombardo

VIDEO ESSAY

Florencia Aliberti, Caterina Cuadros and Gala Hernández

ARTICLES

Lois Weber: the female thinking in movementWeber: the female thinking in movement

Núria Bou

‘One must at least begin with the body feeling’: Dance as filmmaking in Maya Deren’s choreocinema

Elinor Cleghorn

Nothing of the Sort: Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970)

Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin

The Trouble with Lupino

Amelie Hastie

Presence (appearance and disappearance) of two Belgian filmmakers

Imma Merino

Identity self-portraits of a filmic gaze. From absence to (multi)presence: Duras,Akerman, Varda

Lourdes Monterrubio Ibáñez

REVIEW

Jorge Oter; Santos Zunzunegui (Eds.) José Julián Bakedano: Sin pausa / Jose Julian Bakedano: Etenik gabe

María Soliña Barreiro