IDENTITY SELF-PORTRAITS OF A FILMIC GAZE. FROM ABSENCE TO (MULTI)PRESENCE: DURAS, AKERMAN, VARDA

Lourdes Monterrubio Ibáñez

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

The filmic self-portrait has been analysed by different authors as one of the forms of the ‘cinema-I’ described by Philippe Lejeune in Cinéma et autobiographie: problèmes de vocabulaire (1987), and used to transpose the question of autobiography from literature to cinema. The different discursive modes of this ‘filmic writing of the self’ include clearly identifiable devices, such as the diary or the letter, and more elusive ones, like the self-portrait, all of them fusing and confusing in distinct experiences:

‘[…] although the filmic self-portrait is difficult to elucidate, this doesn’t mean that it lacks a playing field, provided that the autobiography’s portrait of a life is replaced by the inscription of life, and the narrative anchor to the discontinuous record of the self, which is regulated by reminiscence and poetic meditation’ (FONT, 2008: 45).

Raymond Bellour, meanwhile, uses Michel Beaujour’s work on literary self-portrait (1991: 3) as a starting point to offer in his Autoportraits (1988) a definition of filmic self-portrait through five attributes, while previously highlighting its differences from autobiography:

‘The self-portrait is thus located on the side of the analogical, the metaphorical and the poetic rather than on that of the narrative: “It tries to build its coherence through a system of mementos, repetitions, superpositions and correspondences between homologous and replaceable elements, in such a way that its general appearance is one of discontinuity, anachronistic juxtaposition, montage”. While autobiography is defined by a temporal closure, the self-portrait appears as a never-ending totality, where nothing can be delivered in advance, because its author announces: “I’m not going to tell you what I did, but rather who I am”. The author of self-portraits begins with a question that reveals an absence from the self, and everything can end up being an answer; he so moves seamlessly from a void to an excess, and doesn’t know clearly either where he is going or what he is doing […]’ (BELLOUR, 1988: 341-342).

Next, the author presents the reasons why digital technology ‘seems to lend itself more to the adventure of self-portrait than cinema does’ (BELLOUR, 1988: 344). These writings of the self were produced in France during modern cinema as a result of the expression of subjectivity in film work, and according to Bellour’s comments on self-portrait, they proliferated from the 1980s onwards.

In L’autoportrait en cinéma (2008), Françoise Grange concludes that the defining essence of the filmic self-portrait lies in the impossibility of its fixing:

‘The film takes its images, erases and replaces them. This permanent absence is a symptom of cinema’s potential to portray the self. Its flux moves through time, it transports a never-completed image in the process of an ever-expanding future’ (GRANGE, 2015: XXIII-7).

In accepting this unavoidable presence-absence dialectic, the author puts forward two considerations that we will take as the point of departure for our study. Firstly, as far as presence is concerned, the notion of self-portrait goes beyond the dimension of mere self-representation:

‘Making a self-portrait does not just mean presenting the actual image, it means proposing a search for the image as an imperceptible, piercing presence of an absence that plagues us all. A self-portrait is a presentation of our obsession with always being someone else, of finding ourselves in an untraceable place that is impossible to locate, when we would so desire to determine its position. Like a leap in the dark, the self-portrait is the experience of a journey through the spaces, times, and layers that run through those worlds we think we inhabit, but which actually inhabit us’ (GRANGE, 2015: XXIII-4).

As Beaujour says: ‘Trapped between absence and human being, the self-portrait must make a detour to produce what will essentially always be an intertwining of anthropology and thanatography’ (1980: 13). Secondly, the self-portrait ‘condenses and presents, on several fronts, a cinematic thinking’, and this implies not only ‘describing the self in cinema’, but also ‘describing cinema itself’. Both qualities ‘give off mirror flashes in which they can observe each other; they can progress together at evolutionary distances’ (GRANGE, 2015: XII-17). Using this characterization, we will call this filmic experience an identity self-portrait, because it seeks the expression of the filmmaker’s identity through her filmic gaze, as the materialization of her cinematic thinking, overcoming the limitations that the application of a mere generic perspective would entail. As Domènec Font says:

‘The “writing of the self” has the same imprecise outlines and the same heretical status as the essay film, and is frequently tied in with it: it is a personal writing that exists within a difficult generic frame rather than in an equally problematic clear characterization’ (2008: 47).

This article aims to discuss and compare the nature of the identity self-portraits of three of the greatest filmmakers in francophone cinema: Marguerite Duras, Chantal Akerman and Agnès Varda. The choice of these three authors is justified not only by their contributions to the shaping of the filmic self-portrait, but also by the engaging itinerary they trace from modern to contemporary cinema through different axes: from absence to (multi)presence, from identity to alterity and intersubjectivity, from fiction to autobiography, from the artistic to the intimate. They are experiences of the filmic self-portrait that share the same, primal desire: to vindicate their status as female filmmakers through cinematic reflection, through their thinking about cinema. As Varda states in Filmer le désir (Marie Mandy, 2002): ‘The first feminist gesture consists of saying […] I look. The act of deciding to look […] the world isn’t defined by how I am looked at, but by how I look at it’.

Marguerite Duras. Coalescent self-portrait in voice and absence

The last period in Marguerite Duras’ film career develops what we have called ‘literary-filmic coalescence’, a fusion of the two artistic disciplines which is produced based on the need to turn into voice the literary text over the film image, with the aim of achieving both literary and filmic narrative deconstruction and artistic destruction (MONTERRUBIO, 2013). One of the most revealing embodiments of modernity’s time-image defined by Gilles Deleuze is produced then, by destroying the sensory-motor schema of classical films’ movement-image and producing ‘the indiscernibility of the real and the imaginary’ (1989: 274). The independence of the visual image and the sound image, the interstice between them and the voiceover’s enunciation as a pure act of speech (1989: 256-257, 278, 243) all generate a coalescent time-image that negates representation and defines what has been called the India cycle –Woman of the Ganges (La femme du Gange, 1972), India Song (1975) and Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta désert (1976). In India Song the filmmaker portrays, for the first time, one of the absent voices of the film, which in the final part becomes the narrator of the sound story.

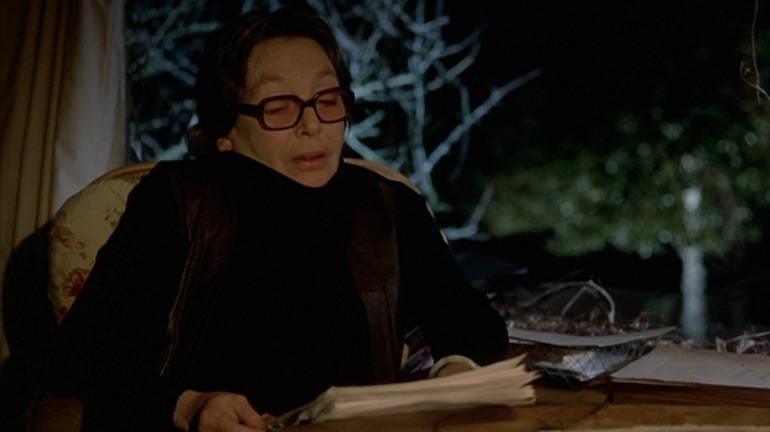

Her next project, The Lorry (Le camion, 1977), was the only film where its maker appears on screen, in the chambre noire space of the reading, where writing becomes voice; from where it is possible to hypothesize a film. We share the views of Grange, who defines this work as a self-portrait: ‘Self-representation in situation (directing actors) turns into the self-portrait of a filmmaker who is inhabited by a particular vision of cinema’ (GRANGE, 2015: XXII-13,16). The filmmaker's self portrait produced during the creative act expresses her cinematic thinking through a filmic gaze that causes narrative deconstruction, just like in the India cycle. This deconstruction, which has, once again, a coalescent nature between literary writing and filmmaking, is produced by ‘the fluctuation between the actual and the virtual’ that Julie Beaulieu analyses (2015: 122). Moreover, the splitting between the reality of the reading (filmmaker and actor) and the film’s invention (the woman and the truck driver) produces an identification between filmmaker and character, thus tackling the creative identity-fictional alterity duality that comes to define the identity self-portrait in the rest of Duras’ filmography. In her conversation with Michelle Porte, the filmmaker says: ‘It’s me [the woman in the truck] as well, of course, as I can be all women […] Anyway, I’ve reached this point: talking about myself as if about someone else, getting interested in myself as someone else would interest me. To talk with myself, perhaps, I don’t know’ (DURAS, 1977: 132). As Youssef Ishaghpour notes, there is an ‘irrepressible identity and duality of Duras and the woman in the truck’, that ‘consists of talking about the self by saying ‘she’: a fickleness of a mental image circulates, without ever taking shape, moving away from Duras towards an indeterminate distance and then returning by projecting itself over her film image to un-make it’ (ISHAGHPOUR, 1982: 263).

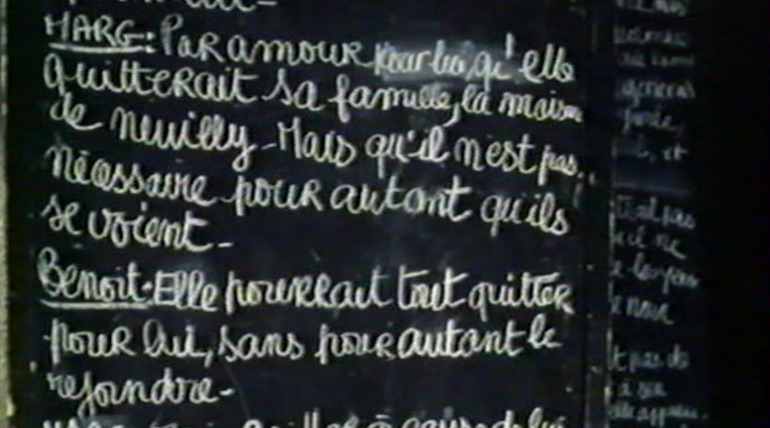

After The Lorry, Duras never appears again in the visual images of her works, switching instead to narrate them all through voice-overs, which fit in with Michel Chion’s definition of I-voice (1999: 49) and more particularly of "textual speech"; with it, Duras attains the inventive dimension of her works: ‘But in comparison with literature, textual speech in film is doubly powerful. Not only does it cause things to appear in the mind but also before our eyes and ears’ (CHION, 1994: 174). Le navire Night (1979) shows once more the two spaces –those of creation and of the potential fiction – that are already present in The Lorry. This time, the voices of Duras and Benoît Jacquot are framed within an autobiographical story about a visit to Athens, as the author herself points out in the prologue to the literary text. The filmmaker’s identity turns once more into a fictional character, this time present just through her voice, in order to narrate a story, once again, about a woman, F., through the negation of her mise-en-scène, which is this time replaced by the space of the set where it should be filmed, and the actors that should perform it. The Durasian self-portrait once again vindicates its creative identity through a shot in the visual image. Among the elements of film creation shown, the camera presents a blackboard on which we can read a piece of dialogue we have just heard between Duras and Jacquot. In this dialogue their respective lines (MARG and Benoît) are identified, offering a visual image of the talking characters’ identity. In this way, Duras’ artistic identity generates a new self-portrait to show her view of the recurrent themes of her creation: the experience of desire and loving passion as defined by the absence of their characters, based on the same creative identity-fictional alterity duality.

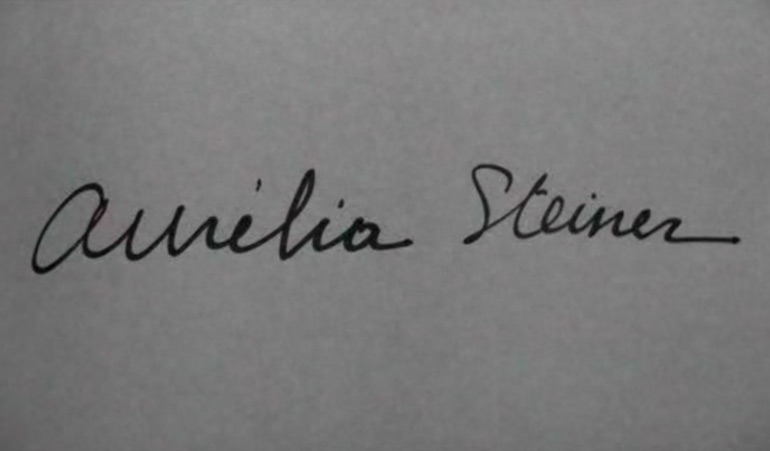

In Aurélia Steiner Melbourne and Aurélia Steiner Vancouver (1979) Duras’ identity disappears completely in order to embody her main character, who is also absent from the visual image. Both Aurélias are embodied in her voice, blending together with it. The author herself explains the identification between filmmaker and character: ‘If you like, when I talk I am Aurélia Steiner […] To wake Aurélia up, even if she is born from me’ (DURAS, 1996: 151). Both the duality in the two abovementioned works and the identification in this case are produced thanks to the characters’ emptying of identity, which in Aurélia is produced through the epistolary mechanism: ‘this name designates strictly what I means: an “empty form”, the mark of subjectivity in its universal and singular dimension’ (VOISIN-ATLANI, 1988: 192). They are female subjectivities which are defined not only by their absence in the image, but also by the omission of their names (the woman in the truck, F.) and/or the absence or contradiction of their biographical references, so allowing the merging with the filmmaker’s identity when insisting on the Durasian vision of desire, passion, incest, identity conflict with the ancestors and, in this case, the Holocaust. These two new Durasian self-portraits in voice and absence offer two crucial images of this identification, which is transferred to the characters. In Melbourne the image of Aurélia could appear on a Parisian bridge, then turning the film screen into a mirror where Duras-Aurélia is reflected. In Vancouver the main character tries to solve her identity conflict through the continuous expression of her name, which becomes voice and writing. Even more so, the inscribing of this name and an excerpt of the text onto the film screen, both handwritten, identify Aurélia’s and Duras’ writing and handwriting.

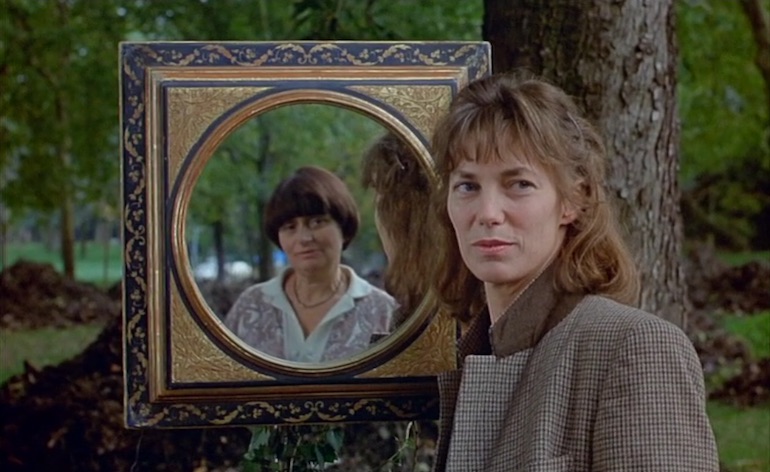

In Agatha and the Limitless Readings (Agatha et les lectures illimitées, 1981) the filmmaker introduces an element that adds a new dimension to the coalescent self-portrait: Yann Andréa, the author’s partner, becomes an actor in the film, along with Bulle Ogier. The work, which narrates the story of incest between Agatha and her brother, is again split in two spaces. The visual image shows two silent characters who go through the hall of a hotel –Roches Noires– and don’t meet until the film’s conclusion. The sound image presents the dialogue between Agatha and her brother at the moment of their final separation. While the visual image is played by Ogier and Andréa, the sound image is produced by his voice and Duras’. The filmmaker embodies once again the main character: ‘It's me, Agatha’ (DURAS, 2014: 139). However, this time the fictional loving alterity is personified by Duras’ real loving alterity, thus densifying the identification between character and filmmaker. Moreover, the visual image is divided between outdoors, on the beach, and indoors, in the hotel. The former, which is identified with the male voice, represents a space of fiction, of diegesis, of the childhood memories of those characters we hear in the sound image, as a symbol of the present absence of the remembrance that is evoked. The latter is constituted, firstly, as an extradiegetic space of Durasian writing, linked with her voice, where the revelation of the film mechanism is once again produced. While the voice of Agatha-Duras articulates a new childhood memory of the siblings, the visual image follows the female character wandering through the hotel. Then the camera is shown in a mirror and the character looks towards it, breaking the cinematic fourth wall and destroying the fiction linked to the outdoor space, so as to reveal the extradiegetic space of the film construction, the writing space.

Ogier’s glance towards the camera is a glance towards Duras, once again creating a superb metaphor for the filmic device as a mirror that produces the self-portrait, a mirror in which both the visual character and the sound character-filmmaker look each other. All of this is possible thanks to the power of the Durasian voice-over, which Ishaghpour discusses in these terms:

‘The voice belongs neither to the representation nor to the presence, it is not representable; instead it determines representation. Through voice, the integral voice-over, Duras rends the magic of cinema as a universe for identification and imaginary fascination’ (ISHAGHPOUR, 1986: 280).

Finally, The Atlantic Man (L’homme atlantique, 1981) is constructed using discarded images from Agatha…, to create a work where more than half of the image is composed of a black screen, over which we hear, for the last time, Duras’ voice. On this occasion this voice formulates the filmmaker’s own conscience, which is no longer narrating a fiction, instead it is directed at the actor Yann Andréa over images of him, mixing them with her reflections on their love relationship over the black screen. Hence, The Atlantic Man rids itself of the fiction of Agatha… to present a last self-portrait of Duras in relation with Andréa’s loving alterity. This self-portrait refers more than ever to absence, which once again brings together the artistic aspect of the work in progress with the more intimate aspect of the love experience: ‘I don’t know any more where we are, at what end of which love, at which start of what other love, in which story we’ve got lost. My knowledge ends in this film. It ends because I know there is no single image that could extend it’. The destruction announced in The Lorry: ‘Let cinema go to its ruin, that is the only cinema’ (DURAS, 1977: 74) is completed in The Atlantic Man. The filmmaker’s voice and the black visual image are the end point of a splendid self-portrait of voice and absence through the Durasian literary-filmic coalescence: ‘Through the drift of the self-portrait, Duras’ films aimed for a mise-en-scène of a conscience of an individualized subject who is the owner of everything’ (GRANGE, 2000: 463). A mise en absence, we might say, of a female authorial conscience that vindicates its condition of filmmaker by taking up once again the primordial feminist gesture described by Varda, and which Beaulieu analyses regarding Duras: ‘a position-taking which leads into a politics and a philosophy in whose center we can find the woman, the author and women (female characters)’, to develop themes previously till then considered taboo, exemplifying ‘the re-appropriation of the woman’s body and its feelings’ (BEAULIEU, 2010: 35-36). It is a feminist gesture that different authors have also linked to the transgression and the subversion of the classical narrative associated with the movement-image (‘subverting the male-centred system of representation of classical and mainstream cinema […] rejecting the traditional perspective of the male gaze’), and particularly with the Durasian coalescent voice:

‘[…] these female voices […] place enunciation on the side of feminine identity, traditionally undermined in narrative cinema. Even more, these female draw attention to social marginality and convey historical memory, establishing a parallel between social, economic, and cultural segregation in patriarchal Western society and off-screen and non-diegetic elements in film representations’ (MAULE, 2015: 38, 56, 30).

This identity self-portrait of a female filmmaker is materialized through the absence of her image and the presence of her voice, to develop in this way the duality-identification between the author and her female characters, in what is the borderline experience, never surpassed, as far as relations between literature and cinema are concerned.

Chantal Akerman. Existential self-portrait in the face of maternal alterity

The presence of Chantal Akerman in her films has taken up different positions. While at the beginning of her career she divided herself into filmmaker and actress in fictional works –Blow Up My Town (Saute ma ville, 1968), The Beloved Child, or I Play at Being a Married Woman (L’enfant aimé ou je joue à être une femme mariée, 1971), La chambre (1972), Je, tu, il, elle (1974)–, in the early ‘80s she showed her presence as a filmmaker of work-in-progress documentaries –Tell Me (Dis-moi, 1980), On Tour with Pina Bausch (Un jour Pina a demandé, 1984), Les années 80 (1983). This dialectic of actress-filmmaker is also explored through the distance and irony of autofiction in The Man with the Suitcase (L’homme à la valise, 1983), Letter from a Filmmaker (Lettre d’un cinéaste, 1984) and Portrait d’une paresseuse (1986). However, the existential self-portrait, using one’s own identity as a film material, is explored in three works that traverse her whole filmography: News from Home (1977), Down There (Là-bas, 2006) and No Home Movie (2015).

News from Home is made by reading the letters that Akerman’s mother sent her during her first, intermittent period in New York, between 1971 and 1974. It is on her second trip to the city, in 1976, when the filmmaker shoots the film material that composes the work. Therefore, the film starts with the filmmaker reading her mother’s letters, while at the same time it shows her perception of the city of New York through the camera. The sound image of the reading of the letters (where the I-voice reproduces a maternal textual speech), as well as the visual image of the perception of the city, the space where they are received, turn into an abyssal self-portrait that brings together the alterity of the maternal gaze on Akerman with the subjectivity of her own filmic gaze, and with both characters remaining absent from the visual image –and, in the case of the mother, also from the sound image: ‘For Akerman, giving voice to her mother’s letter raises ambivalent issues of inheritance and of emotional indebtedness […] Akerman’s voice silences her mother’s in a simulacrum of communication’ (MARGULIES, 1996: 151). The filmmaker offers an image of the generation gap that separates her from her mother, which is an essential Identity fracture in herself and her work, a chasm between the family reality of her mother in Brussels and the professional desires of the daughter in New York. As Brenda Longfellow notes, the film is defined: ‘[…] as evidence of an irreparable divide […] the daughter's insurmountable difference from the mother, a difference that is at once spatial, generational, political and sexual’ (LONGFELLOW, 1989: 79). Thus, the letters are defined by the perceptions of their addressee. The anxious, demanding and constant murmur of maternal worries for her daughter, as well as the insistent asking for news, become an identity attribute of the filmmaker herself: ‘Akerman demonstrates that subjectivity is a function of connexion to others, is constructed within a social context, that it arises and articulates itself only through its relation to others’ (BARKER, 2003: 44). It is a mother-daughter bond which verges on pathological identification: ‘I live at the rhythm of your letters’, where the life experience of the sender depends on the epistolary production of the addressee. Consequently, the self-portrait is built through maternal alterity: the daughter’s perception of how her mother experiences her absence, and the confrontation between this perception and her own identity. It is a self-portrait in maternal alterity that presents its existential depths through the absence of her words and her image, but in the presence of her voice and her filmic gaze.

In Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman (1996) the filmmaker expresses her belief that it is possible to make the desired professional self-portrait through her filmic work. However, the sine qua non condition of the people in charge of Cinéma, de notre temps was that she had to appear in the image and talk about herself, and this stipulation resulted in the film being divided into two parts. In the first, Akerman tries to present the motivations and circumstances that led her to become a filmmaker. In the second, various excerpts from her films are edited without any external comment. Thus it confirms that mere self-representation is absolutely insufficient for generating a self-portrait that springs from a search for a perhaps impossible image. This search actually takes place in the second part, which, ‘containing in fact no image representing the filmmaker, potentially evokes her’ (BEGHIN, 2004: 210). A last shot returns to an image of Akerman looking at the camera and saying her name and birthplace as the only possible truth, perhaps making clear the failure of identifying self-portrait with self-representation. Such an identification would seek an auto-objectivation which is impossible or, at least, pointless. Two years later, the installation Self-portrait/Autobiography: a work in progress (1998) seems to achieve the desire that had remained unattained in the previous film. The images of From the East (D’Est, 1993), Jeanne Dielman... (1975) and excerpts from other films are accompanied by Akerman reading from her novel Une famille à Bruxelles (1998), published that same year. The statement ‘If I make films it’s because I didn’t dare to try writing’, which is present in the first part of Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman, reveals its full importance here. The forced self-representation in the previous film becomes now effectively a search for identity through the reading of an autobiographical story that deals with family narration after the father’s death, to materialize one more time the mother-daughter conflict. Once again, the presence of the voice and the absence in the image generate Akerman’s self-portrait in relation with maternal alterity.

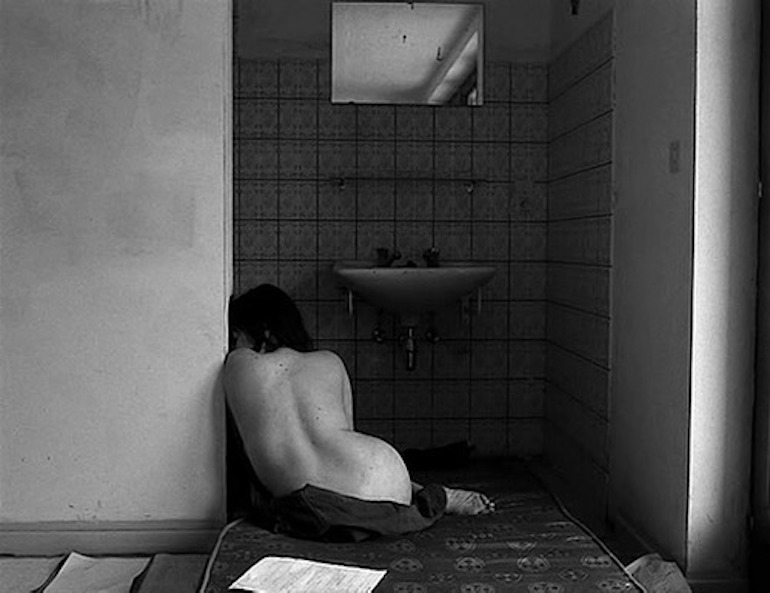

Almost a decade later, Down There shuts itself away inside an apartment in Tel Aviv to offer a new identity self-portrait of the filmmaker. While in News from Home it was possible to identify the film’s point of view with Akerman’s subjective gaze, this time the static camera registers the exterior events through the windows while the author’s presence remains outside the frame, from where we can listen to her movements and actions and the phone calls she makes. This shift of position in relation with News is completed with the advent of her voiceover, outside the space-time shown, from where she releases a flow of conscience that turns the film into a deep, personal diary of a depressive crisis. In this manner, the film becomes a self-portrait of a split identity that transports the mother-daughter chasm in News’ into the filmmaker’s very self, where the filmic dispositive expresses the intimate impossibility of connecting the interior with the exterior: ‘I’m disconnected from almost everything […] I can hardly look, I can hardly hear. Half blind, half deaf. I float, sometimes I sink, but not completely […] To sum up, I don’t know how to live […] There’s something broken in me. My relationship with the real, the quotidian’. We perceive this reality as almost enclosed. Vision is limited through the apartment windows, listening is restricted to the city murmur and the camera detaches from the filmmaker: it no longer shows her subjectivity, it becomes a witness of her retreat, of the ‘immobility and absorption’, so as to generate a film diary where ‘the only thing that remains is the naked and poignant evidence of exterior exile. “I am not fleeing from the yellow star. I’m with it, it is inscribed in me”’ (BÉGHIN, 2011). The off-space of the voice is disconnected from the in-space of the image, as an expression of the identity crisis that Akerman recounts. This interior exile is also revealed through the identity present in Israel, which is also split between its reality and its mythical significance. This identity crisis finds its essential image in the only shot where the filmmaker actually appears (apart from those in the interior of her apartment where she partially enters the frame). The image shows Akerman on the beach, facing away, in the distance, without any link to the camera that is filming her, without any voice-over connecting her to her conscience. By using, on this occasion, the device of the diary, the author manages to create another self-portrait which is produced through the dialectic of presence-absence, both in front and behind the camera in the visual image, both outside the frame and in the off-space in the visual image.

Her last work, No Home Movie, meant overcoming the conflicts with maternal alterity exposed in News… and the identity crisis shown in Down there, to create, at last, a self-portrait of the presence. No wonder that this self-portrait has a literary precedent in her narration Ma mère rit. Traits et portraits (2013), in which it is again constructed from the maternal alterity. The film, which is devoted to the last moments of her existence, cancels out the distance with her and resolves the intimate split. Now both mother and daughter appear and talk in the image. Their presences and their words come together in their bodies to destroy the absence and make the voice-over disappear, just as these two elements had materialized the identity conflict in the previous works. Moreover, Akerman introduces a handheld camera, which turns into an expression of the conciliation between identity and alterity, as it allows the filmmaker to film while she is being filmed by the static camera. Different images disclose the meanings of this final self-portrait in presence. First, mother and daughter share the space –particularly that of the kitchen, whose meaning, in relation to Jeanne Dielman… (1975), is crucial– and conversation, as they remember the family past together, sharing their memories and perceptions. In addition, the filmmaker observes her mother in her daily experience, follows her with the handheld camera while both of them are recorded by the static one. In this way, the creation of the maternal portrait is also a reaffirmation of the own self-portrait, which at last reconciles the artistic sphere with the intimate one. Secondly, the generational chasm shown in News… through the epistolary correspondence is now mitigated through Skype conversations, where mother and daughter are present in voice and image again. The previous distance between them is cancelled out, an idea that Akerman highlights by zooming in on her mother’s image on the computer, until she disfigures it. Finally, and again with the handheld camera, the filmmaker faces her own image through the self-filming, first, of her shadow in the water, and later of her reflection in the kitchen window. Death imposes the mother’s definitive absence, with which both the film and the filmmaker’s career end. Along this career, Akerman offered us a self-portrait of her identity intimacy through her cinematic thinking:

‘[…] what one could call the dramatic formalism of Chantal Akerman resides in forceful strategies of enunciation that articulate, dialectically, impression and observation, subjectivity and otherness, the present and the past […] In a poetics that is also a formal politics, the essential figures of her filmic writing –repetition, ellipsis, interruption– articulate the working of the unconscious (repression, the compulsion to repeat) as they partake of a very personal interpretation of history’ (DAVID, 1995: 62-63).

Through these three films Akerman combines her film poetics and her film politics, her cinematic thinking, to compose an existential self-portrait that evolves from absence to presence, portraying an identity conflict against the maternal alterity that contains various crucial feminist issues. The status of filmmaker is revealed as primary in the intimate need to produce a cinematographic image of herself, offering that first gesture of looking at herself that Varda had talked about.

Agnès Varda. Self-portrait of multipresence and intersubjectivity

The non-fiction cinema of Agnès Varda is mostly defined by the voice-over, first-person narration of the filmmaker, making evident her subjective gaze, as narrator of the film story, in what she has called subjective documentary. This is the case with works like Salut, les cubains! (1963), Black Panthers (1968), Daguerréotypes (1977) or Mural murals (Mur murs, 1981), among others. However, Varda’s sound presence becomes a visual one when it comes to creating a portrait of the other. The one in Oncle Yanko (1967) shows the filmmaker on the screen, announcing so the theory realised in Jane B. for Agnès V. (Jane B. par Agnès V., 1988), a film analysed by Cybelle H. McFadden (2010), in which the portrait of the object requires the presence of the subject who is making it, including a self-portrait of the filmmaker as part of the portrait of the actress. At the beginning of the film Varda explains her theory to Birkin in these terms:

‘[…] it is as if I filmed your self-portrait. But you won’t be alone in the mirror. The camera, which is a bit like myself, will be there, and it doesn’t matter if I appear in the mirror or the frame […] You just need to follow the rules of the game and to look at the camera as often as possible. To look at it squarely, otherwise you won’t be looking at me’.

The filmmaker synthesizes this thesis in a lucid shot. A pan shows Birkin looking at Varda via a mirror, then it shows Varda, and finally it shows the actress looking at the camera through the mirror. In this way, the filmmaker affirms that both the portrait and the self-portrait are generated through the relation with the other, through a film apparatus that turns into a mirror where one must look at oneself: ‘The filmmaker defines a playing field between the camera –a substitute for the eye– and the mirror that returns its gaze, between the portrait of her model-like actors and the self-portrait of the filmmaker who is revealed through her own images’ (RIAMBAU, 2009: 136). A shot of the camera and one showing Varda behind it express the need to include a vindication of the filmmaker’s work within the work itself.

In Jacquot de Nantes (1991) the presence of Varda’s voice-over as the narrator of the story is completed with a series of extreme close-ups of the face and the hands of Jacques Demy, highlighting the presence of Varda’s intimate gaze. This link between subject and object is again synthesized through the filmmaker’s presence and the character’s gaze at the camera. Varda appears in the image in a single, decisive shot; the camera explores Demy’s face, producing a smile, then shows the filmmaker’s hand caressing his shoulder. This hand synthesizes ‘the multiplicity of female figures Varda embodies in Jacquot de Nantes in relation to Jacques/Jacquot: she is at once the filmmaker, the partner, but also Jacquot’s mother, the one who creates, through fiction, the boy that Jacques Demy was’ (LE FORESTIER, 2009: 175). In this way, Varda offers a new, simultaneous portrait-self-portrait, as we can see in the next-to-last shot in the film, where the filmmaker’s voice-over sings Démons et merveilles while the handheld camera looks along the seashore until it meets Demy’s gaze. This simultaneity is also produced in the two later works devoted to the filmmaker, moving from the space of memories to the space of biography: The Young Girls Turn 25 (Les demoiselles ont eu 25 ans, 1993) and The World of Jacques Demy (L’univers de Jacques Demy, 1995).

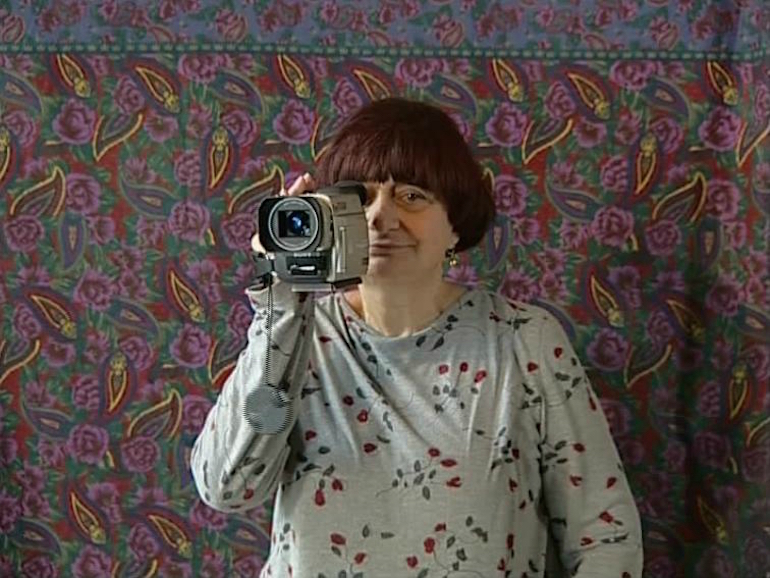

The digital handycam allows the filmmaker to experiment with new possibilities to make her self-portrait in The Gleaners and I (Les glaneurs et la glaneuse, 2000), until she synthesizes her proposal in a particular gesture: ‘This is my project: to film with a hand my other hand. To enter into the horror. It seems extraordinary to me. I have the impression that I am an animal. Worse than that. I am an animal I don’t know’. Varda experiments with self-filming, with the possibility of filming herself while she handles the camera to show how she gathers heart-shaped potatoes, how she catches trucks on the road or how she examines the alterity of aging with the same interest she shows when approaching the people she interviews. Her grey hair and the wrinkles on her hands correspond to the ones in Demy’s portrait in Jacquot de Nantes, showing again the link between identity and alterity. The filmmaker talks about this correspondence between the portrait of the loved one and the self-portrait in the conclusion of The Gleaners and I: Two Years Later (Deux ans après, 2002), where she states, looking at the camera, that she wasn’t aware of the link between the two images. Knowing nothing of his work as a psychoanalyst, Varda by chance interviews Jean Laplanche in relation to his work as a vine grower, and then he presents his antiphilosophy of the subject: ‘the subject finds its origin, first, in the other’. As Claude Murcia states:

‘To think about the other so as to think about oneself, that is what Varda does in her quest for her own alterity […] The Gleaners and I seems to be an attempt at grasping the self, one’s own body and the anguish it generates due to its finite condition. This procedure implies the acceptance of this alterity that constitutes oneself and the other’ (MURCIA, 2009: 48).

The Beaches of Agnès (Les plages d’Agnès, 2008) is created as ‘a new postmodern hybrid between autobiography and self-portrait’ (BLUHER, 2013: 63). It is a hybrid built like a kaleidoscopic collage, where Varda, in addition to being author and narrator, is now the film’s main character. It is a film in which:

‘[…] the subtle sliding toward self-portrait manages to temper and metamorphose the impasses of the autobiography, by opening all kinds of intermediate paths […] equally successfully, it achieves autobiography through the medium of the self-portrait and vice-versa, thus creating by herself, like a hapax, a unique form of use’ (BELLOUR, 2009: 17).

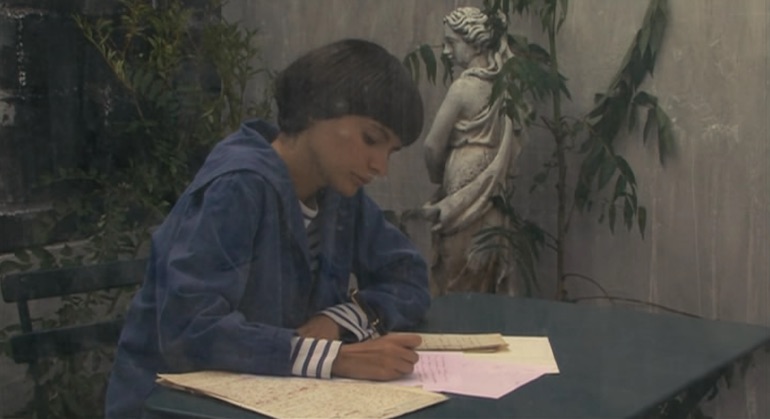

While until that moment the self-portrait had been generated based on the image and voice of the filmmaker, both in front of and behind the camera (self-filming included), and always in relation with her interest for alterity, now Varda uses two new elements to generate what Bluher calls ‘performative self-portraits’ (BLUHER, 2013: 59): autobiographical recreation and the artistic installation. In both cases, real and present Varda as she is now appears offering new, powerful meanings. In the first case, the filmmaker recreates old autobiographical scenes while including herself in them, generating the mise en abyme of the self-portrait in its creative and playful sense: ‘She constantly emphasizes her self-invention […] It is as if Varda created herself, sui generis’ (CONWEY, 2010: 133). In her childhood recreation on the beach Varda puts herself next to her fictional child self-portraits to declare: ‘I don’t know what recreating a scene like this means. Do we relive the moment? For me it is cinema, it is a game’. Later on, she recreates the family environment at Sète, her photographic activity in La Pointe Courte (1955) and the writing of her first screenplay. In this last recreation, self-portrait mise en abyme is produced through the reproduction of the same action in the same space by both presences: the past and fictional, and the real, present one, thus highlighting the experience of subjective time, also in the case of the self-portrait. This is inherent to all Varda’s works we are analysing here.

Concerning the installation, as Bellour points out, this is identified with the notion of mise-en-scène: ‘We find ourselves in a subtle, strange, in-between, where cinema acts as contemporary art’ (BELLOUR, 2009; 19). At the beginning of the film, the installation of the mirrors on the beach shows, once again, portraits of her collaborators and of herself, enabling the installation to contain an experience of the creative self and a new image of her self-portrait. Symmetrically, the film concludes by showing the installation Ma cabane de l’échec (2006), a space that is covered with the photochemical film of the projection copies of The Creatures (Les créatures, 1966), where Varda’s presence generates a new self-portrait that also gives the installation a new and powerful meaning: ‘When I am here I have the feeling that I inhabit cinema, which is my home. I feel that I have always inhabited it’.

Varda’s self-portrait is defined by the filmmaker’s multipresence through different positions in simultaneous devices: in front of and behind the camera; reflected in multiple mirrors; as a fictional recreation which is the product of auto-invention; as an artistic creation in the space of the installation. It is a self-portrait that can only be completed with the portrait of her beloved ones, those whom she mentions at the beginning of the film: ‘[…] the others are the ones that truly interest me and that I like to film. The others, those who intrigue me, motivate me, question me, confound me, excite me’. Among them, the loved ones that are already disappeared, and of course, ‘the most loved among the dead ones’, Jacques Demy. Varda takes up the abovementioned shots of his portrait from Jacquot de Nantes, to now complete them with her words: ‘My only solution as a filmmaker was to film him, from very close: his skin, his eye, his hair, as a landscape, his hands, his blemishes. I needed to do that, shots of him, made from his own matter. Jacques dying but Jacques still alive’. Self-portrait is again defined as a collage-puzzle, constantly transforming and being updated, and that is only possible thanks to the mirror of alterity: ‘Only the movement of our thinking and our emotions can shape a “portrait-puzzle” in a “game of human mirrors” that makes us penetrate into the real and plunges us deeply, to return us its visible and indefinite dimension’ (BLUHER, 2009: 185). This is, then, a self-portrait of multipresence, as a result of an intersubjectivity that goes beyond the dialectic of identity-otherness. Agnès’ identity beaches are always inhabited by others. As she explains regarding her family: ‘[…] altogether, they are the sum of my happiness. I’m not sure if I know them or if I understand them, I just go towards them’.

Varda’s self-portrait is therefore configured as the portrait of her creative experience, of her process of cinematic reflection on that first gesture of how I look, destroying the genre stereotypes. This is a gaze that longs for meeting the others and generates the multiplicity of its own image:

‘Her goal is not only to give expression to her particular voice, but it is to show, to make visible the creative process as she experiences it as an aging woman with a long and formidable career. This process reaps the important benefit of producing the female cinematic body –a composite entity of the filmmaker constructed by the film’ (MCFADDEN, 2014: 70).

Identity, presence and cinematographic thought

The study of these filmmakers’ filmic self-portrait has given us an itinerary from absence to presence which also describes the evolution of cinematic thinking from modern to contemporary cinema. Marguerite Duras generates her coalescent self-portrait of voice and absence through artistic subjectivity, by projecting her identity onto fictional female characters that are absent from the visual image but embodied by Duras through her voice-over. This cinematographic approach materializes in exemplary fashion modernity’s time-image, based on the fusion of literature and cinema, destroying the sensory-motor schema of classical cinema’s movement-image. Chantal Akerman, meanwhile, develops the dialectic of identity-alterity that define postmodernity, by exploring its belonging concepts of extimacy (IMBERT, 2010: 331) and strangerhood (BAUMAN, 1991: 101). In this way, she offers an existential self-portrait facing the maternal alterity, in relation with the diary form, where the presence of the voice-over and the absence of her own image express an identity conflict which is overcome by the presence next to and in front of the other. This filmic self-portrait is moreover located halfway between the previous influence of literature and the new one of visual arts. Finally, Agnès Varda creates a self-portrait of the multipresence and the intersubjectivity that springs from the portrait of the other and the interest for alterity to construct a self-portraiting, a multiple and intermedial collage-puzzle which is produced thanks to the intersection between autobiography and artistic installation. It is an intersubjectivity that goes beyond the dialectic of identity-alterity and that is identified with contemporary cinema. In these three self-portraits, the mirrors of fiction, maternal alterity and intersubjectivity bring us back to the sought presence of the filmmakers to which Grange referred.

This is a route from absence to presence that we can synthesize with the apparition of the beach as a shared element in the three self-portraits. It is a beach that is always deserted in Duras’ films –Aurélia Steiner Vancouver, Agatha…– a space of fiction and absence where a coalescent literary-cinematic self-portrait is projected through the embodiment of different female characters thanks to her writing made voice. It is a beach of shared experience with alterity, where nonetheless Akerman portrays herself as isolated and split –Down There– materializing the identity conflict, and where later on she will meet her image again in the water to film it –No Home Movie– and to show thus its possible overcoming. In Varda’s multiple, always-inhabited identity beaches, the self-portraiting collage manifests an intersubjectivity that goes beyond the dialectic of identity-alterity.

All of these images vindicate the filmmakers’ female status through their respective cinematographic reflections. Duras destroys the rules of the classical narrative to realise a female filmic enunciation using her own voice, which offers her own topics and reaffirms herself as a creator; Akerman experiments with filmic self-absorption and seeks an essential image that must overcome the identity conflict in the face of maternal alterity, and which it is materialized through the dialectic absence-presence it is materialized through the dialectic absence-presence both in the cinematic image and sound; Varda produces a self-portrait of multipresence as a result of her need to look at the other, a work that is born from the intermedial hybridization of all the artistic practices. Creating, looking into oneself and looking at the other as self-portraiting gestures of feminist vindication.

ABSTRACT

The present article aims to analyze the nature of the filmic self-portraits of three of the greatest directors in francophone cinema: Marguerite Duras, Chantal Akerman and Agnès Varda. They all generate an identity self-portrait that shows the essences of their respective filmic gazes. Three self-portraits that describe a route from absence to (multi)presence, from identity to alterity and intersubjectivity, from fiction to autobiography, from artistic to intimate space, from literary presence to that of visual arts, and which share the same primordial desire: the vindication of their female filmmakers’ status through cinematic reflexion. Marguerite Duras only showed her image in one single work, The Lorry (1977), to then embody, through her voice-over, different female characters who remain absent from the filmic image. A duality-identification is then generated between the filmmaker and the fictional characters, and the latter compose a self-portrait in absence of the director in Le navire Night (1979), Aurélia Steiner (1979), Agatha and the Limitless Readings (1981) and The Atlantic Man (1981). Chantal Akerman, while dividing herself into filmmaker and actress at the beginning of her career, created three works that represent her existential self-portrait: News from Home (1977), Down There (2006) and No Home Movie (2015). Films of a diaristic nature where the self-portrait is constructed through the conflict with maternal alterity and self-identity, and which is embodied by the dialectic presence-absence of Akerman in the film. Finally, Agnès Varda creates a self-portrait of the multipresence born from her interest in alterity, from the portraits of others created in Jane B. for Agnès V. (1988) and Jacquot de Nantes (1991), and which she continues in The Gleaners and I (2000). In The Beaches of Agnès (2008) the meeting between autobiography and art installation enables her to generate multiple self-images, present and past, real and fictional, in order to achieve a collage-puzzle of herself.

KEYWORDS

Marguerite Duras, Chantal Akerman, Agnès Varda, self-portrait, filmic gaze, first-person enunciation, identity and alterity, presence and absence.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BARKER, Jennifer M. (2003). The feminine side of New York: travelogue, autobiography and architecture in ‘News from home’. FOSTER, Gwendolyn Audrey (ed.), Identity and memory. The Films of Chantal Akerman (pp. 41-58). Illinois: Southern Illinois Univesity Press.

BAUMAN, Zygmunt (1991). Modernity and Ambivalence. Cambridge: Polity Press / Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Limited.

BEAUJOUR, Michel (1991). Poetics of the Literary Self-Portrait. New York: New York University Press.

BEAULIEU, Julie (2010). La voie/voix féministe durasienne. Intercâmbio. Revista de Estudos Franceses da Universidade do Porto, vol. 2, no 2, L’écriture au féminin : Histoire, apports, enjeux (XIXe et XXe siècles), pp. 19-38. Retrieved from: https://www.academia.edu/3525943/La_voie_voix_f%C3%A9ministe_durassienne_2009_?auto=download

BEAULIEU, Julie (2015). Virtualités à l’œuvre dans le cinéma de Marguerite Duras. PROULX, Caroline y SANTINI, Sylvano (dir.). Le cinéma de Marguerite Duras : l’autre scène du littéraire ? (pp. 115-124). Bruxelles: Peter Lang.

BÉGHIN, Cyril (2004). Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman. PAQUOT, Claudine (ed), Chantal Akerman: autoportrait en cinéaste (p. 210). Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou / Cahiers du Cinéma.

BÉGHIN, Cyril (2011). Quatre temps d’exil. Chantal Akerman. Quatre fillms [DVD] Marseille: Shellac Sud.

BELLOUR, Raymond (1988). Autoportraits. Communications vol. 48, n. 1, pp. 327-387.

BELLOUR, Raymond (2009). Varda ou l’art contemporain. Notes sur ‘Les Plages d’Agnès’.Trafic nº 69, pp. 16-19.

BLUHER, Dominique (2009). La miroitière. À propos de quelques films et installations d’Agnès Varda. FIANT, Antony, HAMERY, Roxane and THOUVENEL, Éric (dirs.), Agnès Varda: le cinéma et au-delà (pp. 177-185). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

BLUHER, Dominique (2013). Autobiography, (re-)enactment and the performative

self-portrait in Varda's ‘Les Plages d'Agnès/The Beaches of Agnès’ (2008). Studies in European Cinema, 10:1, pp. 59-69.

CHION, Michel (1982). The voice in cinema. New York: Columbia University Press.

CHION, Michel (1994). Audio-vison. Sound on screen. New York: Columbia University Press.

CONWEY, Kelley (2010). Varda at work: ‘Les plages d’Agnès’. Studies in French Cinema, 10: 2, pp. 125-139.

DAVID, Catherine (1995). ‘D’est’: Akerman variations. AA.VV., Bordering on fiction: Chantal Akerman’s ‘D’Est’. (pp. 57-64) Minneapolis: Walter Art Center

DELEUZE, Gilles (1989). Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

DURAS, Marguerite (1977) Le camion suivi de Entretien avec Michelle Porte. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit.

DURAS, Marguerite (1996). Les yeux verts. Paris: Cahiers du Cinéma / Édtions de l’Étoile.

DURAS, Marguerite, (2014). Le livre dit. Entretiens de ‘Duras filme’. Paris: Gallimard

FONT, Domènec (2008) A través del espejo: cartografías del yo. MARTÍN GUTIÉRREZ, Gregorio (ed.), Cineastas frente al espejo (pp. 35-52). Madrid: T&B Editores.

GRANGE, Marie-Françoise (2000). La représentation dans le cinéma de Marguerite Duras, de ‘India song’ (1974) à ‘L’homme atlantique’ (1981). BURGELIN, Claude y GAULMYN, Pierre de (eds.), Lire Duras. Écriture –Théâtre– Cinéma (pp. 453-464). Lyon: Presses Universitaires de Lyon.

GRANGE, Marie-Françoise (2015). L’autoportrait en cinéma. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. New edition [online]. Original edition: 2008.

IMBERT, Gérard (2010). El cine posmoderno como experiencia de los límites (1990-2010). Madrid. Ediciones Cátedra.

ISHAGHPOUR, Youssef (1982) D’une image à l’autre. La représentation dans le cinéma d’aujourd’hui. Paris: Éditions Denoël / Gonthier.

ISHAGHPOUR, Youssef (1986). Cinéma Contemporain. De ce côté du miroir, Paris: Éditions de la Différence.

LE FORESTIER, Laurent (2009). Signer, dé-signer, dessiner: La foction auteur dans ‘Jacquot de Nantes’. FIANT, Antony, HAMERY, Roxane and THOUVENEL, Éric (dirs.), Agnès Varda: le cinéma et au-delà (pp. 167-176). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

LEJEUNE, Phillipe (1987). Cinéma et autobiographie: problèmes de vocabulaire. Revue Belge de Cinéma n. 19, pp. 7-12.

LONGFELLOW, Brenda (1989). Love letters to the mother: The work of Chantal Akerman. Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory/Revue canadienne de théorie politique et sociale, Volume XIII, no.1-2, pp. 73-90.

MARGULIES, Ivone (1996). Nothing happens. Chantal Akerman’s hiperrealista everyday. London: Duke University Press.

MAULE, Rosanna (2009). Marguerite Duras, la grande imagière. MAULE, Rosanna and BEAULIEU, Julie (ed.), In the dark room. Marguerite Duras and cinema. Bruxelles: Peter Lang.

MCFADDEN, Cybelle H. (2010). Reflected Reflexivity in ‘Jane B. par Agnès V.’. Quarterly Review of Film & Video, Vol. 28 Issue 4, pp. 307-324.

MCFADDEN, Cybelle H. (2014). Gendered frames, embodied cameras: Varda, Akerman, Cabrera, Calle and Maïwenn, Madison. New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

MONTERRUBIO, Lourdes (2013). La coalescencia literario-cinematográfica en la obra de Marguerite Duras. CARRIEDO, Lourdes, PICAZO, María Dolores, GUERRERO, María Luisa (dir.), Entre escritura e imagen. Lecturas de narrativa contemporánea, (pp. 245-258). Bruxelles: Peter Lang.

MURCIA, Claude (2009). Soi et l’autre (‘Les glaneurs et la glaneuse’). FIANT, Antony, HAMERY, Roxane and THOUVENEL, Éric (dirs.), Agnès Varda: le cinéma et au-delà (pp. 43-48). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

RIAMBAU, Esteve (2009). La caméra et le miroir: portraits et autoportraits. FIANT, Antony, HAMERY, Roxane and THOUVENEL, Éric (dirs.), Agnès Varda: le cinéma et au-delà (pp. 145-143). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

VOISIN-ATLANI, Françoise, (1988). L’instance de la lettre. SIESS, Jürgen (dir.), La lettre. Entre réel et fiction (pp. 97-107) Paris: SEDES.

LOURDES MONTERRUBIO IBÁÑEZ

BA in French at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, where she obtained her PhD with the thesis La presencia de la materia epistolar en la literatura y el cine franceses: tipología, evolución y estudio comparado [The presence of the epistolary matter in French literature and cinema: typology, evolution and comparative study]. Previously she studied Filmmaking at the ECAM (Escuela de Cinematografía y del Audiovisual de la Comunidad de Madrid). She has written film criticism for the magazine Cahiers du Cinéma. España. As a specialist in relations between literature and film in the French context, she has published ‘La coalescencia literario-cinematográfica en la obra de Marguerite Duras’ in Entre escritura e imagen. Lecturas de narrativa contemporánea, Peter Lang, 2013. Her latest publications are ‘Del cinéma militant al ciné-essai. Letter to Jane de Jean-Luc Godard y Jean-Pierre Gorin’ (L’Atalante, vol. 22) and ‘Juventud en marcha de Pedro Costa. La misiva negada. Palabra, memoria y resistencia’ (Secuencias, vol. 45).

Nº 8 PORTRAIT AS AN ACTRESS, SELF-PORTRAIT AS A FILMMAKER

Editorial. Portrait as an actress, self-portrait as a filmmaker

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

About the femenine

Maya Deren

About Fuses

Carolee Schneemann

Conversation about Wanda by Barbara Loden

Marguerite Duras and Elia Kazan

About the Film-Diary

Anne-Charlotte Robertson

Nothing to say

Chantal Akerman

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

About the Women Film Pioneers Project

Alejandra Rosenberg

Medeas. Interview with María Ruido

Palma Lombardo

VIDEO ESSAY

Florencia Aliberti, Caterina Cuadros and Gala Hernández

ARTICLES

Lois Weber: the female thinking in movementWeber: the female thinking in movement

Núria Bou

‘One must at least begin with the body feeling’: Dance as filmmaking in Maya Deren’s choreocinema

Elinor Cleghorn

Nothing of the Sort: Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970)

Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin

The Trouble with Lupino

Amelie Hastie

Presence (appearance and disappearance) of two Belgian filmmakers

Imma Merino

Identity self-portraits of a filmic gaze. From absence to (multi)presence: Duras,Akerman, Varda

Lourdes Monterrubio Ibáñez

REVIEW

Jorge Oter; Santos Zunzunegui (Eds.) José Julián Bakedano: Sin pausa / Jose Julian Bakedano: Etenik gabe

María Soliña Barreiro