CONVERSATION WITH ERYK ROCHA: THE LEGACY OF THE ETERNAL

Carolina Sourdis (in collaboration with Andrés Pedraza)

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / INTERVIEW / FOOTNOTE / ABOUT THE AUTHORS

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / INTERVIEW / FOOTNOTE / ABOUT THE AUTHORS

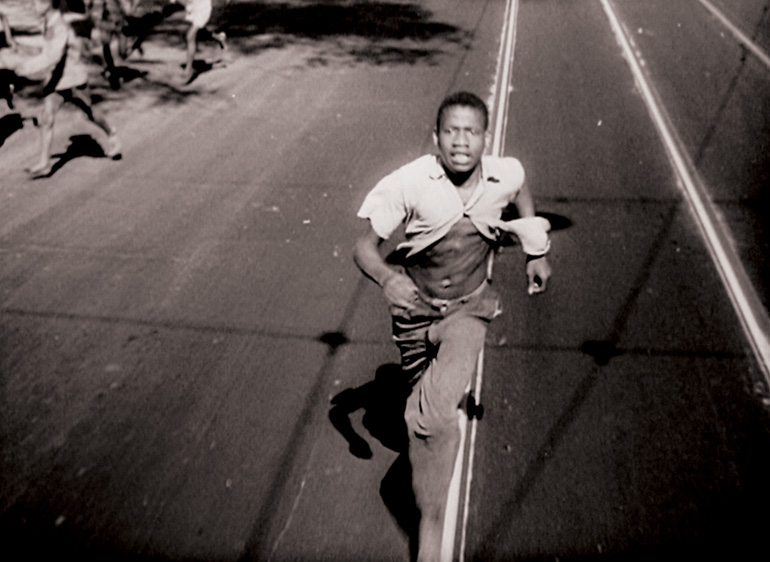

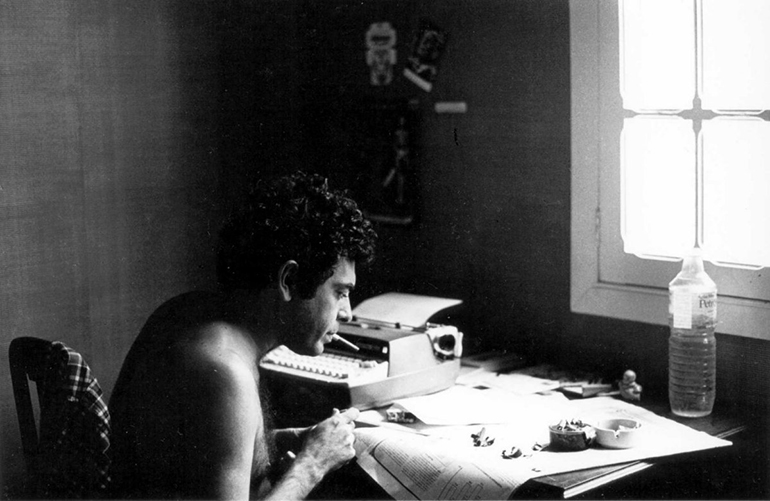

This conversation with the Brazilian filmmaker Eryk Rocha took place during the 18th International Documentary Film Exhibition in Bogotá (MIDBO), Colombia, held between the 24th and the 30th of October. We discussed with him about the validity of the ideas of Cinema Novo, about the aesthetic and political proposals of the current Brazilian filmmakers, and about the relationships that he has created with the legacy of this cinema movement through his films. Eryk Rocha has lived in several Latin American cities: Bogotá, La Habana and Brazil, where he was born and where he is currently living. He has made seven documentary features, including Stones in the Sky (Rocha que Voa, 2002); Transeunte (2010), about the Brazilian singer and songwriter José Paes de Lira; Sunday Ball (Campo de Jogo, 2014), and Cinema Novo (2016).

You recently released Cinema Novo in Cannes. It is a film entirely made out of excerpts of Cinema Novo films. What moved you towards the making of this film?

Now that some time has passed, I think I could say three things about Cinema Novo to start the conversation. In the first place, I made this film to understand better where I come from, not only regarding my affective origins, that is, where I come from as a person, but also regarding my origins as part of the cinematography and political history in my country. In the second place, I live in Brazil and we are now undergoing a very difficult political moment. I needed to understand why I want to keep making films, what I want to say and what is my need of making them; this is my seventh film already. My third point comes out from here, and it is to try to understand better my country nowadays. Even though the starting point of the film is Cinema Novo, I think it is a film about the present. It is a result of a dialogue between generations. It is based on the dialogue between my generation and the 60s generation, my father’s and many other Brazilian filmmaking masters. I think that these three points are three motivations, three passions that made me do this film.

Even your first feature film, Stones in the Sky, was going in this direction. In a way you were already questioning the relationship between the cinematographic past and the political past, and the possibility of showing the current world, from the reconstruction of the generation of the 1960s and its cinema ideals. What bonds can you see now between Stones in the Sky, which you made 14 years ago about your father during his exile in Cuba, and Cinema Novo, which includes a whole generation of filmmakers?

I made Stones in the Sky after finishing my studies in San Antonio de los Baños, in Cuba, when I was 24 years old. I lived in La Habana for a year with two friends who had studied with me at university, one Brazilian and one another French-Uruguayan. Although the film has to do with Cinema Novo, the focus of Stones in the Sky was more opened to the Latin American and Cuban cinema and in particular to the relationship between my father, Glauber Rocha, and the Cuban cinema when he was exiled there for a year, in 1971, right in the middle of the military dictatorship in Brazil. So Stones in the Sky is more of a reverse shot of Cinema Novo, because it talks about another moment of Latin America. But of course, both films have a strong dialogue. I think they are complementary. Between these two films I made five feature films and several shorts, and many other projects; it is interesting that my first film was a declaration of love to my father, to cinema and to Latin America. I think that every cinema intended to be cinema is something very personal. It grows from one’s relationship with the world; it is a necessity, an urgency. I went back to these origins 14 years later and I asked myself essential questions regarding why I kept making films and about what is now happening in Brazil. In this sense, I am very happy with the connection of Cinema Novo with the present. The archives of the film aren’t dead archives... I even find the word archive a bit complicated. Many times I find of documentary film terms very complicated... ‘Archives’, it sounds like something from the police... It is related to ‘depoimentos’, testimonies. It sounds horrible! It is a term that immediately gives you a sense of past.

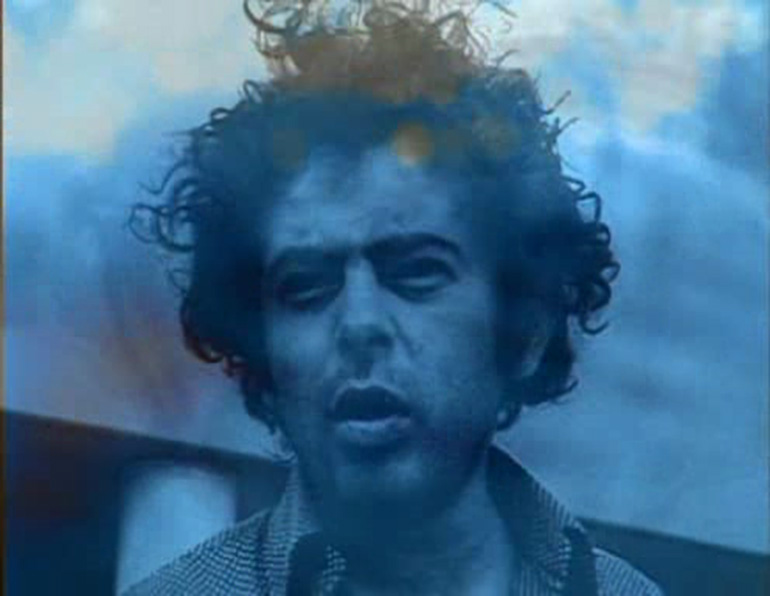

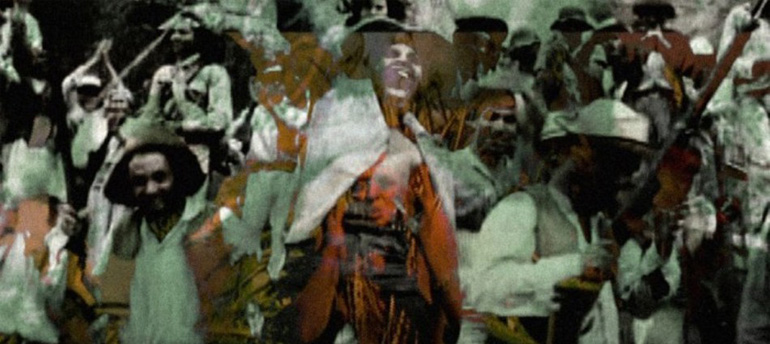

However, in Cinema Novo the archive is not the past, it is rather a memory in motion, just as the title of the festival1 suggests. It is not a stagnant memory of the crystallized, idealized, romanticized past. We often talk about the 1960s and we tend to idealize, to romanticize, to the nostalgia... Fortunately my film has nothing to do with this. It is a memory, but in terms of the Brazilian poet Murilo Mendes, who stated that the memory is a construction of the future. This is the memory in motion, and this is what interests me the most about archives. Even for the film I shot many things that were discarded during editing. Everything that was shot today with Cinema Novo filmmakers, those who are still alive, everything was discarded. This is because, even if it is a paradox, those materials that were filmed today created a feeling of past for the film, whereas everything from the archive created a feeling of present. It has to do with the construction of language that we were looking for, with poetics, with a transfiguration of the Cinema Novo forms.

Yesterday we were discussing about the personal implication of the filmmaker, about how every film is, in a way, a personal discourse which is comprised by a collective portrait which at the same time determines certain visual forms. How do you face today in the editing these poetics of the Cinema Novo when you talk about the search of a language, and of transfiguration? How do you face this process of intervention of images from the past to activate what you feel that is still prevailing and can be shown in the future, as a memory of your country and its cinema, in a new structure?

It took us nine months to edit the images, and then three months to edit the sound. We worked full-time on the film for a year. Undoubtedly the body of the film is made of many segments, of dozens of fragments. The heart of the film is the montage, which from different segments and fragments results in a new dramatic and poetic body. I play a lot with that. I always say that it is not a film about Cinema Novo, it is a film through Cinema Novo and with Cinema Novo. I never had the ambition of making a film about anything; I think it is a wrong starting point trying to make a film about something. The about already anticipates some control, it is a totalizing idea, and I think that a film is not made to form a totalizing idea about anything; about anticipates control; it is a somewhat arrogant vision. I am much more interested in dialog, this through... How I go through the film and how the film goes through me.

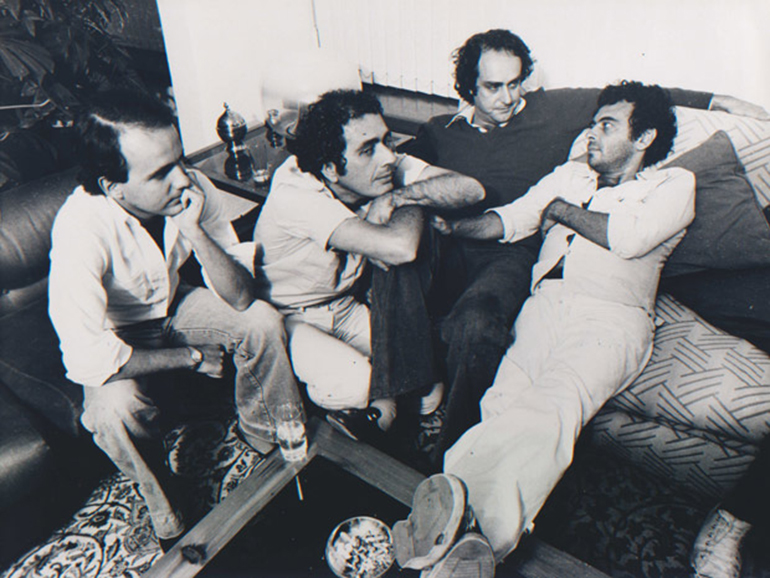

The essence of the film is how we −I talk of we because it is me, the editor of the film Renato Valona, who is a fundamental person in the creation, and Edson Secco, who edited the sound with me− incorporated this creative, aesthetic, political and spiritual energy of Cinema Novo. How we incorporated this in the construction of the film. I was never interested in doing something about Cinema Novo that was biographic or incidental, in which I could explain what Cinema Novo is, because I feel it is very complicated to explain such a complex movement. 50 years had to go by for this film to be made, and it is not a coincidence, it is because it is a fundamental movement not only in cinema, but in Brazilian and Latin American culture. So I wasn’t interested in trying to do something about, in drawing conclusions or finding a definition. It is rather a dialogue. That is why I think it is a film essay, because it suggests a dialogue about how to incorporate this energy of transfiguration. It is undoubtedly the most complex film I have ever made. There are at least 15 masters of Brazilian cinema, there are more, but let’s say there are 15 fundamental filmmakers. We used 130 films, as well as archives of Brazilian and international television channels, home-movies of the filmmakers, sound archives, and some of the recordings of the interviews we filmed today, very few.

So the big challenge was how to connect with these materials, to settle the starting points of the montage, of this construction. The first starting point was to avoid creating any mediation between past and present. We didn’t want to show the filmmakers, now old, talking about what Cinema Novo was. This was completely out from the montage. We wanted to create the film just with archives, which was a big risk. How can you renew the film in every sequence with only archives, with black and white films, often in a precarious state? Another fundamental starting point of the editing was to narrate the film in first person. This narrative polyphony emerges from the creators, the authors of Cinema Novo. There are no critics, no historians, no intermediation. We didn’t include anything that could be used as interpretation, anything that could be used as a mediation to explain what Cinema Novo was. The film emerges, then, from within, from the emotion, the adventure of creation. It emerges from those authors.

Going back to one of the points you stated as a motivation to make Cinema Novo... A big part of the strength of this movement, and in general of the so-called New Latin American Cinema, lied in the need of constructing categories of thought which were strictly Latin American and which emerged from cinema itself, within creation. It is difficult to say whether this was achieved or not. Nowadays, so long after, how does your film deal with the possibility of putting together a Latin American thinking, in relation to what you said about searching a cinematographic and political past at the same time, in relation to the longed-for union between politics and aesthetics?

The 1960s are present today. There are characteristics and fundamental problems that are very similar to those we lived 50 years ago, problems that are still open and unsolved. But in every age there are very specific issues, and it is interesting to think about that. In Brazil we have just undergone a coup of the media, the parliament and the legal sector. Cinema Novo was a generation that underwent the interruption of the democratic process through a military coup, a coup d’état. So these cycles of interruption and starting over are a tradition in the Latin America tragedy. We undergo interruptions of the democratic processes all the time and we have to start over. And this tragedy, which happens not only in Brazil, but in many Latin American countries, is also a key to the inspiration for the montage of Cinema Novo.

Not only in Brazil, but all over the globe, this need of thinking about aesthetics and its relationship with politics is something very present, very urgent and very necessary. The 1960s generation planted a very important seed on that subject and now it is returning very strongly, and it is very necessary. I think that my film is a small seed too, an attempt to contribute to this matter. Politics do not have a way out. The ordinary citizen that walks in the streets of Rio de Janeiro, of Bogotá, Caracas or Buenos Aires experiences politics intensely. Nowadays we are living something that I never thought our generation would experience. There was another coup, another interruption in the democratic process, a polarized country, a very violent and strong neo-fascism. A setback. Life comes first than cinema, and I live this intensity as a citizen. It is not only my concern, but that of any person walking in the street, who has to wake up to work in any area. It affects life, it affects any person and it affects cinema too. Cinema is nourished from that relationship with life. The contemporaneity of this aesthetic-political thinking of Cinema Novo lies there. What makes Cinema Novo an extremely original movement is not only to make films about political issues, but films with political issues and political forms. Politics is found in the language of films and in a new model of production. That is why this cooperation between politics and aesthetics is the big trace of Cinema Novo, and I think the big trace of the best cinema tradition in Latin America.

In this sense it is interesting to talk about your film Sunday Ball. You suggest very well there this kind of very intimate relationship between politics and aesthetics and, especially, the implication of politics in the daily life of the citizen, in his daily experience. This film uses body-language, it focuses on expressions of pain, of emotion, and it totally avoids the words. You don’t do any interview, there aren’t any testimonies or anything that tries to clarify or present the situation. However you can feel its dramatic progression, you can feel the rise of the collective ecstasy created through football. It is also felt as an ambiguous ecstasy with this insistence in the contact between bodies which is passionate and almost violent. How is this film still linked to the precepts of Cinema Novo, how does it renew its legacy?

One of my biggest passions is football and I always wanted to make a film through football and with football. During the investigation I realized I was not interested in industrial, multi-million dollar football; besides, the World Cup in Brazil was about to take place. We decided with my assistant that we would not shoot in the Maracanã Stadium: television does it every day. So we decided to make a film about popular football. Actually, Brazilian football was born in those popular fields, but unfortunately this has been forgotten and now Brazil wants to copy the European way of playing, despite the fact that Germany was inspired by Brazil to reinvent its football and become world champion. Brazil began to imitate the worst of Europe. This is the complex of colonialism suffered in Latin America. We want to bring the worst while people are expecting something from us. The film, among other things, tries to be a metaphor of this.

At the beginning I wanted to make the film in several places in the suburbs of Rio, in several popular dirt fields. But we found a field in the neighborhood of Sampaio, in the north, which we felt that contained every field: it was surrounded by several favelas, there was an annual championship going on and it was two kilometers away from Maracanã. It is curious because it was a coincidence, but it was next to the big stadium. We arrived there, we started getting closer to the people, becoming friends, frequenting the area and, before we realized, we were already shooting the film. This is very common. The films are faster than you are. It is not you who make the film, it is the film that makes you. And you have the feeling that the film is pulling you to one direction. We shot the whole championship until the big final. There were 14 teams and each team represented a different favela. The final was between Geração and Juventude, the teams of two favelas that were historically rivals because of drug dealing issues.

At the editing when we tried to make a version of the film by editing the whole story of the championship, we realized that we got a very fragmented result, it became something incidental. It was when we realized that this great final of the championship, this final between Geração and Juventude, carried itself a real drama. It even had a dramatic structure, so we focused the whole film on it. The playwright Nelson Rodrigues said that even the smallest football game, in any corner, is a Shakespearean tragedy. Many times in the field, the space for happiness, for ecstasy, is also a space for war. In fact, I think this is a very strong characteristic of Latin America: the permanent coexistence of tragedy, war and happiness. I think it is something that strongly coexists in our nations.

So the film is first of all a counterpoint to official football: it is a field next to Maracanã where the final of the World Cup is played, and it collects millions of dollars. It is the richest industry in the world. It also has millions of cameras, so filming a popular field of street football, filming the final of a championship between favelas, filming that area of the city, where a majority of black youngsters live, most of them without jobs or opportunities, becomes a political act. Besides, these fields are disappearing. The spaces are being appropriated for the real estate industry. That is to say, they are also being robbed. The popular football field is, maybe, the last democratic space for the people, where the people can move around, meet each other. If you watched the transmission of the World Cup, everything in high definition, in the end that is what it showed. You could see no black people in the panoramas of the stands because the tickets were very expensive. The working-class has been excluded from the stadiums in Brazil, which is supposed to be the country of football.

However, next to Maracanã, barely two kilometers from it, there is a field where there is still place for the popular resistance. This field becomes a reflex of the country. In these favelas there are only churches and drug trafficking, and therefore the field represents a lot: it represents these people’s culture, the culture they possess. Every Sunday, as a ritual, they go there, they meet in this field to play soccer, to play this championship. This field is a space for celebration, for invention, a political and meeting place. There would probably be more violence without this field. Football is the way these young people can canalize their energy and their creativity, their anger and violence. Also playing football is a dance. Football has a very powerful, dramatic, extremely strong body and visual language; it is a trance. Sunday Ball is a highly political film through this perspective; it doesn’t talk sociologically about what favelas are or how many deaths drug trafficking caused. The film doesn’t need it, it confronts the spectator with this visual power. I wanted the film to be an almost theatrical suggestion, where the spectator was present like he was in that field, in that place in the neighborhood of Sampaio; that is also why it is very choreographic.

Besides this political and aesthetic search inside the cinematic language and the artistic forms, Cinema Novo and the New Latin American Cinema looked for a collective synchrony. There were some artistic movements established, movements linked to national projects, to an idea of country and continent. Specifically in Brazil, this idea of collectiveness was transplanted in a very rich and powerful dialogue between many artistic fronts: music, cinema, literature... It wasn’t exclusively cinematographic. The forces and the movements affected every area. What happens now with this idea of collectiveness, with the possibility of common dreams in a whole generation of artists? Can we still think of a common cultural force, of an artistic impulse that creates a collective movement?

We now live in an age of collapse, an emotional collapse, an economic, social and political collapse. That is the current world. There is a collapse and the lack of collectiveness is a consequence of this. I think there are some embryonic movements that wish to reconstruct collectiveness. There may be some hints or signs of this in Brazil. There are some groups and movements that seem to be being born, but they are still getting shape, we do not know where they are going. Nevertheless, I think that this idea of movement itself does not exist anymore, the idea of a movement like there was in Cinema Novo.

The idea of collectiveness that existed in Cinema Novo, where there were music, cinema, literature movements, is very present in my film. If you look at what Cinema Novo was, apart from being a group of very talented and courageous artists, there was a great fondness, a great and deep friendship between them. They were a brotherhood. There is a moment in the film when Carlos Diegues says something like ‘We weren’t friends because we made cinema; we made cinema because we were friends’. They were friends because they admired each other’s films, in the essential sense, an admiration to one another. You rarely see that nowadays. I am part of a new Brazilian cinema, I have similarities with several authors, this exists but it is not strong enough to start a movement, we are still lacking that. We need more aggressiveness linked to a project, more deepness and more understanding of the age we are living in.

Nowadays projects are individual. In the 1960s there was this idea of national cinemas: Brazilian cinema, Argentinian cinema, Cuban cinema. I think that our generation has the challenge to reinvent and rebuild the idea of collectiveness. There are new models of communication, of technology, new ways of production and organization are outlined, there are some impressions of this. Some attempts. There are things forming, there are germs, seeds. But actually, which cinematography in the current world can be defined as so? At some point there was an Iranian cinema, now maybe it doesn’t exist anymore. There was an Argentinian cinema in the beginning of the 1990s, but what about now? Much less a Brazilian cinema. There isn’t the idea of a united movement, or a unity that can constitute a movement. I don’t think so. However, there are individual searching projects and similarities between artists that work together. Maybe today is a more interesting moment in this sense than ten years ago.

One would think that this individuality following the economic openness in the 90s in Latin America is somehow broken by the development of left-wing projects, the fact that Hugo Chávez, Lula da Silva or Néstor Kirchner came to power. How does this affect the current Brazilian cinema? This vision of unity that is materialized in economic policies such as UNASUR or MERCOSUR... How are they brought to the fore in culture? Nothing is agglutinated from there?

I think this individualism is a result of the age that not only affects cinema, but everything. The challenge of cinema to create new aesthetic movements, new unions, it the same challenge politics has to reenchant politics. The emptiness in the idea of collectiveness exists in every area. What you said about the late 1990s, this big rehearsal of Latin America, this simultaneity existed in many countries, is something that happened especially in the sense of an economic integration and, maybe, of an ideology or a sense of being Latin American. Lula was essential for Brazil to look more at Latin America and yes, there were changes, it is true, there was another feeling. But this integration never was consolidated culturally, which was one of the biggest mistakes of those left-wing political projects. Lula had some initiatives, but much fewer than expected and, besides, he didn’t give enough importance to the culture and communication in the contemporary world. They didn’t understand. Unfortunately the left in Latin America didn’t have vision of what culture and communication are regarding their strategic importance, even of what education, in a broad sense, is. This is one of the reasons why the project failed. They always understood integration from an economic point of view. I don’t want to generalize, but that is what I think that happened. There are projects, vanishing points, some things that can be saved. During the first mandate of Lula, the Ministry of Culture, led by Gilberto Gil, was incredible and sowed very interesting things, but more in Brazil rather than in Latin America.

And in a moment where films like City of God (Cidade de Deus, Fernando Meirelles, 2002) or Carandiru (Héctor Babenco, 2003), which deal with Brazilian problems and marginalization, set themselves up as representatives of the Brazilian cinema both in specialized festivals and in commercial circuits, what do you consider the legacy of Cinema Novo is in complementing or controverting these types of approaches?

I don’t think they are a rupture, or that they have inherited the spirit of Cinema Novo. They took the key issues of the Brazilian society and of Brazil, and they grasped them to put them into the perspective of advertising cinema, of commercial cinemas, of the ‘universal’ cinema. There are North American filmmakers in every country. North American filmmakers are not only in the United States: there are a lot of them in Colombia, in Brazil, in Argentina. A friend said that globalization did not exist, that there was rather an anglobalization. What happens is that this kind of cinematographic product is, once again, a result of our age, of an idea of commercial cinema, of an idea and an ambition of a type of ‘universal’ communication that feeds from American cinema and from advertisement. Thus, using the key issues of poverty, it applies the formula of a certain commercial cinema, which is in the end a fake political cinema, an entertainment cinema dressed up as political cinema. I don’t like it and I don’t get hooked on it, but there is space for diversity, some people like it. There are referential works in the Brazilian cinema, and they are a path, a vision of cinema, an ideology of cinema, that reaches many places because they have the majors, the international distributors that allow these films to circulate a lot.

Now that you mention distribution and circulation, it is worth considering where the Cinema Novo and its manifestos were received, isn’t it? In the end, the New Latin American Cinema reached the importance it has today, partially, because of the validation it got from Europe, and this plays a crucial role which, in a way, contrasts with the anticolonialist ideals that these cinemas had. Aesthetics of Hunger (Estética da fome, 1965), as a manifest, is still totally prevailing because the ideological and cultural colonization is still prevailing as well. How do you sense this and how are the ideas formulated by the Cinema Novo filmmakers being actualized?

I think the question itself is the action. A five centuries long problem cannot be solved in five decades and that is why Aesthetics of Hunger, the manifest, is so prevailing. Because... what happened after the manifest of Aesthetics of Hunger in Brazil? 21 years of military dictatorship. What happened after a fake openness that promised a democracy that never existed? The first elections in Brazil in 1989, in which the media chose Collor de Mello. A sham! And now? The coup. Making these films can be a way of catharsis. It is what we were talking about before, this notion of dialoguing between generations, of aesthetics and politics. I think it has to do with anthropophagy. Each generation devours what has been done before, with love and inspiration, and with respect; but not to repeat it, but as an inspiration to reinvent things. Because history is in motion, not stagnant.

There are motions and there are forces that transcend their own age. There is an Italian critic called Adriano Aprà, who was a close friend of Rossellini; he said something that had a great influence on me. He was asked: ‘Adriano, after all, what is Italian neorealism?’ He said: ‘Italian neorealism is a spiritual state’.

I think there are movements like neorealism, or the French New Wave, or Russian constructivism and many others, that appear in a certain moment and in a certain country, with certain authors that have a significant common base. But they are above all a spiritual state. They are movements that can be analyzed from a historicist perspective, from a history context. This is a layer. But for me it goes way beyond that. They are boundless movements, because they are forces that appear to get even with the world or to try to beat it, as is constantly threatening to defeat us. They bring with them a vital experience of the citizen and the author. What exactly wants Cinema Novo? It wants to look at Brazil, to interpret it. To take the cameras out of the studios, the big cameras, and take them to the streets to look at the Brazilian people, to look at the Brazilian reality, to try to confront the military coup. It is important to say that most of the production of Cinema Novo came out during the dictatorship in Brazil. That is why it is very strong, very contemporary, an attitude facing the world, a certain urgency of understanding the world and our realities. This is fundamental nowadays. It seems to me that Cinema Novo is much more interesting as an aesthetic philosophy of thought. You watch films like Barren Lives (Vidas Secas, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, 1963), or like Black God, White Devil (Deus e o Diablo na Terra do Sol, Glauber Rocha, 1964), or like The Guns (Os Fuzis, Ruy Guerra, 1964), for example, and these are films that transform over time, that gain new meanings with every new generation.

They gain new layers of ways of looking...

Yes, that is what seems more contemporary to me about Cinema Novo. And what I see as the original force of the movement is this symbiosis between politics and aesthetics that we mentioned before. I have the feeling that in the current cinema, form is separated from content. I watch absolutely beautiful films, but they are often so formalist, that they become sterile, they lack courage. In other times I watch totally activist films, films that denounce something, which is essential, but I feel that there is a separation of these two aspects in current cinema. I don’t want to generalize, but I think that we need to take risks to cross these borders and connect these two forces. It is incredible to see how many Cinema Novo films mix the two ends brilliantly, so that form and content become one. You don’t see form and content anymore, you see a cascade, the language of the film is what comes at the forefront, and I find this is everlasting.

Glauber Rocha says at the end of the film: ‘Well, Cinema Novo ended, but no, actually it didn’t end because the idea of novelty is everlasting’. This is the idea of Cinema Novo as something prevalent, that is, the idea of novelty is present, is opened. The idea of novelty is a possibility that revives in each generation. And it is everlasting because it is in motion, because the possibilities of cinema, which is such a young art, barely a child that cannot die so early, are oceanic. It has a huge experimentation field, a lot of political and poetic possibilities. The same happens with anthropophagy, it is a spiritual state. Oswald de Andrade’s anthropophagy isn’t there to be repeated. It is more like an inspiration, like an essential mold to transform it, because everything is transforming. What interests us are the roots, the seeds and how we are transforming this energy.

FOOTNOTE

1 / International Documentary Festival in Bogotá (MIDBO), where this conversation took place, had as a central topic ‘Memories in motion’.

ABSTRACT

This conversation deals with the prevalence of the ideas of Cinema Novo through the work of the filmmaker Eryk Rocha, by discussing his process of creation and his relationship with the legacy of this cinema movement in which his father, Glauber Rocha, was an essential figure. In addition, it questions the strength of collectiveness in art within the Brazilian and Latin American political context nowadays, and it stresses the relationships between politics and aesthetics highlighting the need to keep constructing a Latin American way of thinking from cinema.

KEYWORDS

Cinema Novo, New Latin American Cinema, Eryk Rocha, political cinema, cinematographic movement, Latin American thought, aesthetics-politics.

ANDRÉS PEDRAZA

He is a winner of several national grants in script writing from the Fondo para el Desarrollo Cinematográfico de Colombia and pre-doctorate researcher in the Department of Social Communication of the National University of La Plata, Argentina. His research is focused on the emergence of popular audiovisual schools during the presidency of Álvaro Uribe Vélez in Colombia from a political, historical and communicative point of view.

CAROLINA SOURDIS

Producer and audiovisual researcher trained in Bogotá and Barcelona. Her audiovisual works have been displayed in festivals in Spain, Colombia and Iran. As a researcher, she has worked about the editing and the practice of found footage, supported by the Ministry of Culture of Colombia. She is a pre-doctorate researcher in the Department of Communication in the Pompeu Fabra University. Her research is focused on the essay drifts of European cinema and the convergence points between cinematographic practice and theory.

No 9 EZTETYKA

Editorial. Eztetyka

Albert Elduque

DOCUMENTS

Revolution

Jorge Sanjinés

Tricontinental

Glauber Rocha

Godard by Solanas. Solanas by Godard

Jean-Luc Godard and Fernando Solanas

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

A combative cinema with the people. Interview with Bolivian filmmaker Jorge Sanjinés

Cristina Alvares Beskow

Conversation with Eryk Rocha: The legacy of the eternal

Carolina Sourdis (in collaboration with Andrés Pedraza)

The necessary amateur. Cinema, education and politics. Interview with Cezar Migliorin

Albert Elduque

ARTICLES

Reading Latin American Third Cinema manifestos today

Moira Fradinger

From imperfect to popular cinema

Maria Alzuguir Gutierrez

The return of the newsreel (2011-2016) in contemporary cinematic representations of the political event

Raquel Schefer

ImagiNation

José Carlos Avellar

REVIEW

TEN BRINK, Joram and OPPENHEIMER, Joshua (eds.) Killer Images. Documentary Film, Memory and the Performance of Violence

Bruno Hachero Hernández

MONTIEL, Alejandro; MORAL, Javier and CANET, Fernando (coord.) Javier Maqua: más que un cineasta. Volumes 1 and 2

Alan Salvadó Romero