THE RETURN OF THE NEWSREEL (2011-2016) IN CONTEMPORARY CINEMATIC REPRESENTATIONS OF THE POLITICAL EVENT

Raquel Schefer

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Perhaps I filmed to fight against.

(Robert Kramer, Berlin 10/90, 1990)

Contemporary cinematic representations of the political event (2011-2016) point to an ongoing dynamic dialectic of ‘structuration’ and ‘destructuration’ (LUKÁCS, 2012, 1968)1 of the film forms, transposing the terms of Lukácsian literary theory into cinema aesthetics. In the works of Jem Cohen and Sylvain George documenting, respectively, Occupy Wall Street (USA), 15-M (Spain) and, more recently, Nuit Debout (France), the return of the newsreel highlights the link between the economic structures and the film manifestations, while indicating a dynamic process of formal evolution. From the soviet newsreels to the work of Cohen and George, passing by the New Latin American Cinema (Santiago Álvarez, Glauber Rocha, Raymundo Gleyzer and Cine de la Base, etc.), and the North-American Newsreel Group, newsreel’s dynamics enables to reconsider, from both a historical and a formal perspective, the relationship between aesthetics and politics, as well as the established distinction between avant-garde/experimental and political cinema. These issues will be examined in this article through the operation notion of ‘form-event,’ which allows to reconcile two dimensions of the aesthetic production: one, which considers art as a reflection; another, which examines it in terms of its outcomes. Newsreel’s formal development from the post-war until the political and cultural contexts in which it has currently evolved brings up a more enriched genealogy of political filmmaking, revealing complex relationships –and a web of influences beyond national film canon– between historical political cinema and the ‘state of the form’ (JAMESON, 1992) of this cinema.

The newsreel as a film form

The newsreel is one of the major and most constant film forms in the history of cinema. Prevalent in the first half of the twentieth century, persisting in the second half of the century, namely through its destructuration by the aesthetic (Jonas Mekas) and political (Jean-Luc Godard’s ciné-tracts, Dziga Vertov Group, among other examples) avant-gardes (WOLLEN, 1975), the newsreel constitutes a transhistorical and cosmopolitan film form. Shaped in 1911 by Charles Pathé, and characterized in its earliest period by the predominance of its informative nature over the aesthetic dimension, as well as by standardized film procedures, newsreel’s language would be soon reinvented by individual filmmakers and filmmaker’s collectives. Dziga Vertov’s newsreels series constitute one of its first historical moments of destructuration.

In 1918, shortly after the October Revolution, Mikhaïl Koltsov, who headed the Moscow Film Committee’s weekly newsreel section, hired Vertov as his assistant. In this frame, Vertov worked together with Lev Kuleshov and Edouard Tissé. Vertov began editing documentary footage and became an editor for 43 issues of Kino-Nedelya, the first Soviet weekly newsreel. The film footage was compiled into organic newsreels, which were then distributed by agit-trains and agit steamboats all across the Soviet Union. The full-length film The Anniversary of the Revolution (Godovshchina revolyutsii, 1919), for instance, was entirely composed of assembled newsreel footage. In 1919, the filmmaker co-founded the Kinoks, a film collective which defended newsreel, in line with Lenin’s conceptions, as the film form of the Soviet Revolution. Vertov defined newsreel as ‘revolutionary cinema’s path of development [sic]... It leads past the heads of film actors and beyond the studio roof, into life, into genuine reality, full of its own drama and detective plots.’ (VERTOV, 1985a: 32) In 1923, with regard to newsreel and Kinoglaz’s (Kino-eye) theory (the camera as an instrument, much like the human eye, to explore the events of everyday life), he considered ‘Kino-eye as the union of science with newsreel to further the battle for the communist decoding of the world, as an attempt to show the truth on the screen’ (VERTOV, 1985b: 41-42).

In 1922, Vertov started the Kino Pravda newsreel series, a movie version of the Party paper, Pravda. Bill Nichols argues that Vertov’s film praxis, founded on newsreel, and his theoretical writings were fundamental in delimiting documentary as a film genre (NICHOLS, 2001). Annette Michelson states that ‘Vertov’s concern with technique and process’ led to ‘a disdain of the mimetic’ (MICHELSON, 1985: XXV). In his turn, Nichols considers that ‘Kino-eye contributed to the construction of a new society by demonstrating how the raw materials of everyday life as caught by the camera could be synthetically reconstructed into a new order’ (NICHOLS, 2001: 218).

If Vertov’s newsreel series are a decisive step in the development of another film form –archival footage’s appropriation (a significant trend of Soviet Film School, which can also be found, for instance, in Esfir Shub’s filmography)–, the ‘reconstruction’ of ‘everyday life’ ‘into a new order’ through film editing creates tension between the raw materials as indexical traces, and its re-organisation and re-signification within a formal system problematising realism, and mimetic tradition. Vertov plays with all the possibilities of film editing, disregarding formal continuity and chronology to accomplish a poetic representation of ‘reality’. Problematising the relationship between film and reality, representing actual and possible worlds, Vertov’s newsreels series lie at the edge of two conceptions of the aesthetic production: one, which, following the blueprint of Marxist aesthetics, considers art as a reflection of reality; another, which recognizes its outcomes on the social field and on the aesthetic sphere, including in terms of transformative mimêsis.

From that moment on, newsreel, in its non-dominant form, would combine powerful innovation –to the point of even denaturalising the film medium– with political engagement. Newsreel would evolve in a powerful and dynamic tension between formal experimentation and political content. To trace the history of newsreel as a film form implies then to examine its destructuration moments, which often coincide with revolutionary periods: the Soviet Revolution, as stated before, Cuban Revolution, as well as, among other possible examples, Portuguese and Mozambique revolutions. The cases briefly studied in this article point towards ‘form-events’ or ‘film-events’, that is, film representations which not only reflect ‘reality,’ but which also transform cinematic history and general history through aesthetic innovation and political engagement.

A brief history of newsreel’s destructuration moments ‑ I

The Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (Cuban Institute on Cinematographic Arts and Industry, ICAIC) was the first cultural institution created after the Cuban Revolution in March of 1959. The law of the Congress of the Ministers of the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Cuba giving birth to the ICAIC defines cinema as ‘the most powerful and suggestive medium of artistic expression and dissemination and the most direct and extensive vehicle of education and popularization of ideas’ (Cine Cubano, 140, 1998: 13). This is the framework within which ICAIC began producing the Noticiero ICAIC Latinoamericano (ICAIC Latin-American Newsreel), a weekly newsreel shown from 1960 to 1990 for a total of 1493 editions of about ten minutes each.

The law creating the ICAIC states explicitly its programmatic lines: placing cinema between art (‘the most powerful and suggestive medium of artistic expression’) and pedagogy/propaganda (‘the most direct and extensive vehicle of education and popularization of ideas’), it anticipates the direction of film policy in Cuba. For Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, ‘Cuban cinema emerged as one more facet of reality within the revolution. Directors learned to make films on the march... They interested viewers more by what they showed than through how they showed it’ (GUTIÉRREZ ALEA, 1997: 108). The crew of the Noticiero ICAIC Latinoamericano was indeed formed by technicians with little training, such as Álvarez, who was the sole director of the program for over three decades. Nevertheless, the subsequent development of Cuban revolutionary cinema would soon find a balance between content and form. Maintaining a productive tension between political engagement and formal experimentation, the ICAIC newsreels exemplify one of Third Cinema’s major concepts, Julio García Espinosa’s notion of ‘imperfect cinema’.

In his seminal article Por un cine imperfecto (For an Imperfect Cinema, 1969), García Espinosa affirms the potentiality of contingency (namely of technical contingency) in relation to film’s representative principle as a necessary step towards the ‘abolition of “elites” [sic]’ (1979: 24), the transformation of the spectators into ‘agents’ (1979: 24), and therefore the elimination of the separation between the subject and the object of representation. In García Espinosa’s words, ‘imperfect cinema is no longer interested in quality or technique. It can be created equally well with a Mitchell or with an 8 mm camera, in a studio or in a guerrilla camp in the middle of the jungle. [...] The only thing it is interested in is how an artist responds to the following question: What are you doing in order to overcome the barrier of the “cultured” [sic] elite audience which up to now has conditioned the form of your work?’ (1979: 26). In line with the conceptions of other Latin-American filmmakers, such as Rocha (the concepts of ‘aesthetics of violence’ and ‘aesthetics of hunger’, developed in 1965 manifesto Estética da Fome [Aesthetics of Hunger], which is quoted in the article [ROCHA, 2015], Ruy Guerra (the notion of ‘aesthetics of possibility’ [GUERRA, 2011]) or Octavio Getino and Fernando ‘Pino’ Solanas (‘Third Cinema’ and ‘Liberation Cinema’ [GETINO AND SOLANAS, 2015]), García Espinosa argues that the aesthetics of imperfection would not only be a means to achieve a decolonized and non-dominant (GRAMSCI, 2012; ALTHUSSER, 1973) cinema –affirming the specificities of Cuban and Latin-American culture–, but that it would also constitute a new poetics of cinema, defined as a ‘“partisan” [sic] and “committed” [sic] poetics’2 (1979: 25). This operative poetics is approached as a transformative poetics, i.e., as a poetics reflecting the ‘revolutionary process,’ but also transforming it, contributing to ‘abolish artistic culture as a fragmentary human activity’ (1979: 25), leading art ‘not to disappear into nothingness’ (1979: 26), but to ‘disappear into everything’ (1979: 26). Suggesting the suppression of the aesthetic sphere, the disappearance of artistic specialization, and the ‘possibility of universal participation’ (1979: 25) –therefore the unification of the subject and the object of representation–, García Espinosa considers that the goal of this new poetics is ‘to commit suicide, to disappear as such’ (1979: 25). This position is close to the perspective assumed by the young Karl Marx in the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. In this philosophical work immediately preceding 1845 ‘epistemological break’ (ALTHUSSER, 1973), art is defined as the prefiguration of the intensified sensibility of men liberated from historical alienation. Aesthetic production does not respond to the real collective consciousness, but instead to a possible consciousness, a consciousness to come (MARX, 2007). This position would be later reviewed by Marx, namely in the third volume of Capital. Literature –French Realism– is perceived a contrario as the reflection or the representation of a given socio-economic reality, and therefore located at the level of the ideological superstructures3, the prevailing conception of Marxist aesthetics.

The New Latin-American cinema cannot strictly be regarded as a remarkably eclectic aesthetic movement, constituted by extraordinary cinematic œuvres, but as a theoretical praxis (ALTHUSSER, 1973) of cinema, including a corpus of speculative texts, and mobilizing, as Soviet Cinema before, a set of new modes of film production and distribution. In this sense, the ICAIC’s cinematic corpus, along with its structures of production and distribution, and the theoretical approach of some of the filmmakers working at the institute, exemplify this transcultural horizon. With a significant documentary production involving newsreels, but also including fiction films –as Gutiérrez Alea’s notable Memories of Underdevelopment (Memorias del subdesarrollo, 1968)–, the ICAIC’s structures of production and distribution exemplify García Espinosa’s ‘imperfect cinema,’ a cinema which affirms the potentiality of contingency. The ICAIC newsreels were produced very fast, often with obsolete technical equipment. The newsreels were filmed in cellulose acetate support with ORWO magnetic sound. Copies in 35 mm were made for the movie theaters, and in 16 mm to be distributed throughout the country by the cine móvil (mobile cinema). Furthermore, the ICAIC’s corpus is predominantly constituted by ‘film-events’ insofar as these films do not only represent (or reflect) the Cuban and the international revolutionary processes (ALTHUSSER, 1973), but they also transform the history of cinema –providing the formal basis for Cuban, Latin-American and Third Cinema– and general history – modifying the perception of recent and historical events.

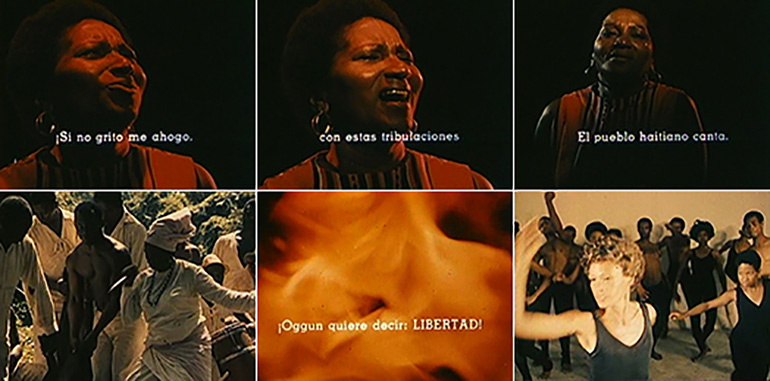

The ICAIC’s production leads thus to reconsider the relationship between art as a reflection of ‘reality’ (a major problem in cinema due to the indexical nature of the film image) and as a productive force, categories which themselves suppose an exchange, and a dynamic tension, between political content and formal experimentation. Within this framework, the ICAIC worked on two inseparable fronts: on the one hand, reviewing history and actuality; on the other hand, transgressing the canon. Álvarez states that the formal innovation of his films emerges as a response to the dominant newsreels (ÁLVAREZ, 1970). In his view, ‘the urgency of the Third World, this creative impatience in the artist produce art of this period, the art of the lives of two-thirds of the world population’ (ÁLVAREZ, 2009). Álvarez’s Now! (1965), perhaps the best-known ICAIC newsreel, and Humberto Solás’ Simparelé (1974) stand as examples of these two gestures: rewriting history and actuality through aesthetic innovation and canon transgression. Both films propose a counter- or a non-hegemonic aesthetics, the first one innovating newsreel through new forms of narration, editing, archival footage’s appropriation, use of soundtrack, and détournement strategies (DEBORD and WOLMAN, 2006); the second one refreshing cinematic reenactment. In Now!, the image takes on a new dialectical legibility, a restitution which is the condition for the emergence of counter-actuality. In Simparelé, dialogism ensures a ‘counterpoint’ (FERRO, 1993: 13) to the history of Haitian Revolution, and to its repercussions in the history of the continent.

The ICAIC newsreel’s formal procedures and the theoretical assumptions underlying their paratext may be inscribed in the genealogy of Soviet Cinema. However, this historical declension also constitutes a major destructuration moment of the newsreel as a film form. At this exceptional moment in time, newsreel finds itself in conflict with dominant structures, which are destructured. This process gives rise to a new structure, which is oriented toward a new state of equilibrium, shaping New Latin American and Tricontinental aesthetics. At the same time, newsreel is redefined not as essentially a vehicle for propaganda, but, conversely, as a film form driven by a politico-aesthetic emancipatory logic. The ICAIC newsreels’ ability to make cinema appear as a site of confrontation, allowing images to make visible political transformation, along with their aesthetic procedures can indeed be found in a broad and heterogeneous range of Latin-American films from the 1960s and 1970s, from Rocha’s Maranhão 66 (1966) and 1968 (a collaboration with Affonso Beato) and Solano and Getino’s The Hour of the Furnaces (La hora de los hornos, 1968) to Raymundo Gleyzer’s Swift, Comunicados Cinematográficos del ERP n° 5 y 7 (1971), and Marta Rodríguez and Jorge Silva’s The Brickmakers (Chircales, 1964-1971), among many other examples.

The Noticiero ICAIC Latinoamericano collaborated in the creation of other national newsreels in countries like Nicaragua (INCINE Newsreel) and Panama (GECU). However, its influence goes beyond Latin America. In the aftermath of Mozambique’s independence, for instance, a Cuban delegation that included Álvarez4 visited Maputo to form technicians from the National Institute of Cinema (INC) as part of an ICAIC’s program for training African film professionals. The aesthetics of Kuxa Kanema, Mozambican national newsreel program, was clearly influenced by the ICAIC newsreels.

Ismail Xavier highlights a singular turn which takes place in the 1960s: from an aesthetic point of view, Brazilian Cinema Novo and the New Latin American Cinema question ‘the teleology implying that it is up to the core countries... to produce the cutting-edge artistic experiences’ (XAVIER, 2007: 12). For the first time in the history of cinema, the Northern hemisphere is represented in the cinema of the Southern hemispheric countries, as, for instance, in Rocha’s Claro (1975), a film in which the Third World permeates and tropicalizes the ruins of the ancient world. For the first time in the history of cinema, the cinemas from the South have an aesthetic impact –and an intrinsically political impact, within a framework of reciprocity– on the cinemas from the North. In 1967, Rocha states that ‘Jean-Luc Godard is the heir of cinema novo [sic]’ (ROCHA, 2006: 311). One can actually note the influence of New Latin American Cinema’s aesthetics on Dziga Vertov Group’s filmography, while the ciné-tracts and the cinegiornali liberi manifest heavy influences from the ICAIC newsreels, although their genealogy can be traced back to Soviet Cinema. Also in the context of the Portuguese Revolution of 1974-1975, filmmaker’s collectives such as Grupo Zero and Cinequanon produce newsreels clearly influenced by the ICAIC newsreels.5

A brief history of newsreel’s destructuration moments ‑ II

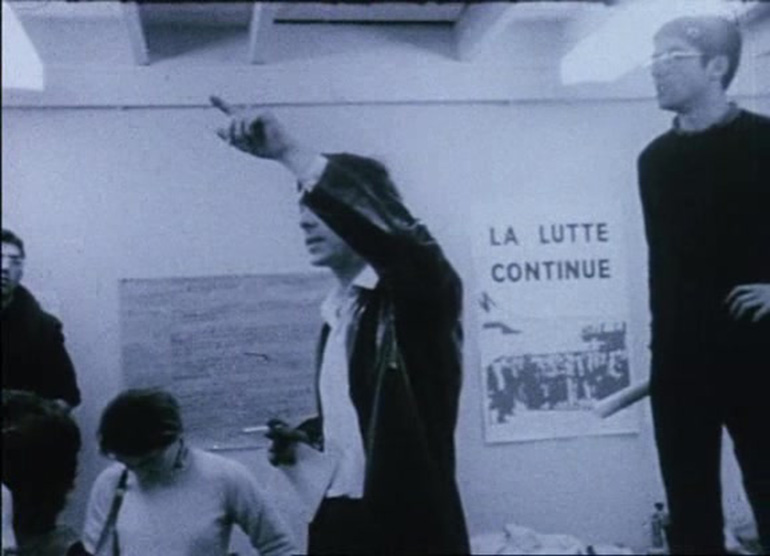

The Newsreel Group, a filmmaker’s collective, is created in 1967 in New York to produce and distribute militant cinema. The Newsreel Group stood for collective forms of film production and played an important role in the 1960s political movement in the USA. The cooperative documented, for instance, the 1967 March on the Pentagon, the occupation of Columbia University in 1968 and the Chicago Democratic Convention in the same year. Films as The Case against Lincoln Center (1968), or Off the Pig (1968), one of the first films made about the Black Panther Party, including footage of Panther recruitment and training6, testify the influence of the ICAIC newsreel’s aesthetics on the collective.

Newsreel’s subsequent destructuration would be achieved by Kramer, one of the founders of the Newsreel Group. In an interview to Cahiers du Cinéma in 1968, Kramer states that a revolutionary movement was then under construction in the USA, adding that there was no distinction between ‘our’ political role and ‘our’ role as filmmakers (DELAHAYE, 1968). The subjective dimension of political change was already at that moment a central point of Kramer’s thought: ‘We are politically engaged in all sort of things not only as filmmakers, but also as political filmmakers and even as individuals without a camera, with our bodies’ (DELAHAYE, 1968: 51). For Kramer, who brilliantly uses the metaphor ‘a maison qui brûle’ (‘a burning house’), quoting Luis Rosales, to characterize Hollywood in the 60’s, the conception and praxis of political cinema would thus imply to rethink the aesthetic forms departing from politics. In the Winter 1968 issue of Film Quarterly, which dedicates a special feature to the Newsreel Group, Kramer defines the collective’s cinema: ‘Our films remind some people of battle footage: grainy, camera weaving around trying to get the material and still not get beaten/trapped. Well, we, and many others, are at war. [...] We want to make films that unnerve, that shake assumptions, that threaten, that do not soft-sell, but hopefully [...] explode like grenades in peoples’ faces, or open minds like a good can opener’ (KRAMER, 1968-1969).

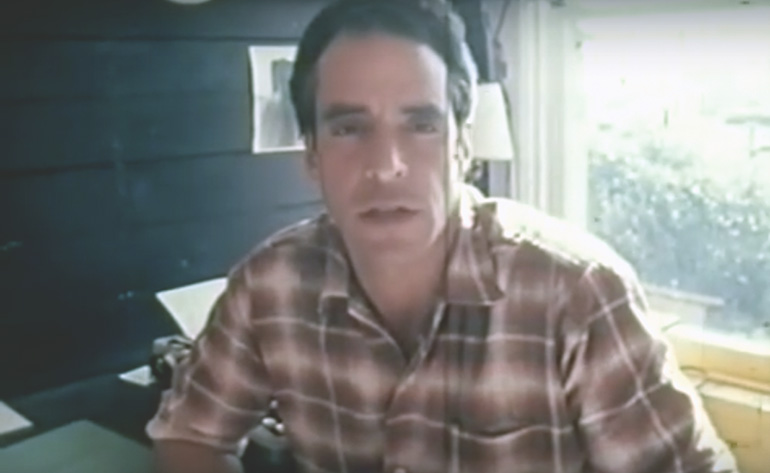

The cinema of Robert Kramer possesses the power of articulating politics and subjectivity, and the ability of thinking technology creatively. These characteristics are inseparable from a formal research related to the transition to a lived cinema, in which politics is permeated by subjective experience, and collective history is beset by memory. Kramer tackles the framework and the methodology of militant cinema: his cinema affirms, in its most corporal dimension, politics of subjectivity and politics of desire.

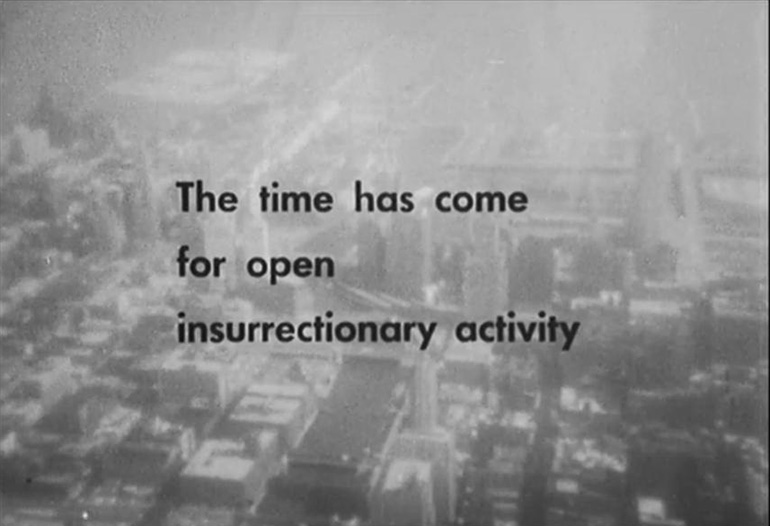

Kramer directs Ice (1969) against this background. The film retraces the story of a New York militant group in the context of COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program, a CIA’s covert program to disrupt domestic political organizations), and of political struggle’s radicalization. The film’s uncertain temporality is considered to be an example of ‘prospective cinema’ by Dominique Noguez (1987: 62), as it represents a time to come, reinforced by the diegetic imaginary war between the USA and Mexico.

Ice’s mise en scène, its grainy image, its long sequence shots, the focal changes and the rupture of all forms of naturalism, particularly when representing situations of loss of sight or loss of control, owes more to the New American Cinema and to the New Latin-American Cinema stylistic forms than to those of militant cinema. However, militant cinema is present in the film as a metanarrative element through the didactic short movies directed by the fictional militant group that intercut the plot. The aesthetics of these short movies is symptomatically very close to that of Newsreel productions and of Kramer’s first movie, FALN (Fuerzas Armas de Liberación Nacional, 1965, co-directed by Peter Gessner), entirely edited with images shot by the Venezuelan guerrilla fighters, which insists that revolution would imply the adoption of reinvented forms of life and the creation of a new ideal human being.

Militant cinema is questioned and formally overcome by Ice. To Nicole Brenez, engaged cinema, on the contrary of militant cinema, do not ‘remain indifferent to aesthetic questions’ (BRENEZ, 2011). Quite the opposite, ‘the cinema of intervention exists only insofar as it raises the fundamental cinematographic questions: why make an image, which one, and how? With whom and for whom?’ (BRENEZ, 2011) Ice is an engaged film that critically contains militant cinema as an objectual metanarrative element. The complex role Kramer plays in the film as one of its leading actors detaches it as well from the militant cinema. In one of the central sequences, Robert, interpreted by Kramer, is emasculated by the secret police. The punishment emphasizes the imbrications between politics, subjectivity, and sexuality while the plot’s ulterior development indicates a clear separation from the Newsreel Group’s programmatic line.

The subjective and authorial marks of Kramer’s films were in fact at the edge of militant cinema, achieving a destructuration of the newsreel as a film form. Indeed, Ice was rejected by the Newsreel Group for its subjectivism and its political position. It would only be released in 1970 because the Newsreel Group considered that to distribute it officially would mean to acknowledge the cooperative’s support for armed struggle groups, which some of its members would join subsequently. According to Eric Breitbart, at that moment member of Newsreel, Ice contributed to ‘prematurely put an end to the group’ (BREITBART, 2001: 212).

In Milestones (1975), as in Ice, we find a collective body, a political community composed of a constellation of individual bodies in the process of becoming – Mary, who is going to be a mother; Terry, the demobbed GI, who is killed by a cop; Helen (the writer and filmmaker Grace Paley), who edits a film about Vietnam War; the political militant who just came out of prison and wants to become a blue-collar... However, the film is not only a communitarian or a generational portrait of the New Left, but, instead, a cinematic essay on the equation between the collective and the subjective, the limits and contradictions of militancy, bodies’ implication in the political struggle, and biopolitical regulations. To Serge Daney, the film’s ‘cast of [...] bodies [...] creates neither a fresco, nor a chronicle, nor a document but a “fabric” [sic]’ (DANEY, 1976: 55). The patchwork of stories’ entanglement emerges from their material articulation as much as from the lacunae, the intervals, and the ellipses. The narrative is also structured by certain scenes of intense physicality and synesthesia: the delivery, one of the film’s central sequences; Gail’s attempted rape scene, which construction breaks definitively the border between documentary and fiction; John, the blind potter, interpreted by John Douglas, the film’s co-director and one of the Newsreel Group’s founders, the one who cannot produce images but objects, living for that reason on the margin of postindustrial society.

There is also a becoming-Indian in the film, particularly present in the employ of ethnographic forms to represent the hippie community, which is inspired by Kramer’s biographical background. The transformation is mentioned by one of the characters – ‘living in the desert [...] becoming Indian’. The inserts that punctuate the film convoke a historical reverse angle, retracing the history and the iconography of slavery, state repression, and biopower technologies in the USA. There is an outside that is gathered by the film, an attempt to inscribe those bodies in the ‘contrived corridors’ (ELIOT, 2002) of history, a movement which has as a counterpoint the effort to redefine the outside, to revise national history departing from a singular intersection of subjectivities.

Scenes from the Class Struggle in Portugal (1977-1979), co-directed by Philip Spinelli, destructures the newsreel as a film form. On the one hand, the narrative is structured by the confrontation of two different temporalities and spatialities: 1975-1977, the years of the shooting in Portugal; San Francisco in 1978, the space and time of the film’s prolog and epilog. Temporal and spatial distance favor an analytical representation of the Portuguese Revolution, which is conceived as a dynamic process. There is an explicit subjective mediation of the Revolution’s representation, enacted through the voice-over, the modes of enunciation, the graphics and, particularly, the prolog and the epilog.

The subjective, self-reflexive and self-referential dimensions of the prolog and the epilog locate Scenes from the Class Struggle in Portugal in a very fragile ground at the frontier of political cinema and self-portrait. The film affirms self-portrait’s potentiality as a political form in opposition to militant and documentary’s film ideology of objectivity, transparency, and purity.

Scenes from the Class Struggle in Portugal results from a reflection on dialectic pairs embedded in the notion and praxis of the Revolution. These pairs are set out in the successive intertitles: ‘events/history, facts/principles, actuality/potentiality [...] words/images [...] history/memory’. Kramer’s dialectic thought finds its formal equivalences in the multitemporal narrative structure and in the editing’s fragmentary and discontinuous dynamics, highlighting the interstitiality announced by the film’s Balzacian title. The abrupt cut of the newsreels by the intertitles make visible the in-actuality of actuality. This in-actuality of actuality is also present in the interval between the shooting and the editing processes, made visible by means of three elements: the prolog and the epilog’s dating, the intertitles, and the voice-over.

Alongside with Rocha’s segments of the collective work The Guns and the People (As Armas e o Povo, 1975), another full-length film on Portuguese Revolution, Scenes from the Class Struggle in Portugal –and, in general terms, the whole cinema of Robert Kramer– represents a moment of destructuration of the newsreel as a film form. The representation of reality is consciously filtered by subjectivity, while the ‘impure’ aesthetic and narrative procedures render visible the inactuality of actuality. The subjectivization of newsreel takes place in a period of a self-referential turn of cinema. Extending the tradition of pictorial and literary self-portrait, self-referential film forms impregnate the work of filmmakers such as Chantal Akerman, Juan Downey, and Godard. The proliferation of self-referential forms, unifying the subject and the object of representation, highlight a significant trend of the political cinema in the 1970s.

Newsreel’s ‘state of the form’

Contemporary cinematic representations of the political event point to an ongoing dynamic dialectic of ‘structuration’ and ‘destructuration’ (LUKÁCS, 2012, 1968) of the newsreel, and to the crossing of boundaries between the ‘objective’ and the ‘subjective’/’self-referential’ declensions of this film form. The problem of the dynamic formal phenomena is wide and complex, and it cannot be dealt with exhaustively within the framework of this paper. The self-referential turn of cinema in the 1970s would culminate in the so-called ‘creative documentary,’ documentary’s contemporary canonical model. The peak of ‘creative documentary’ is symptomatically accompanied by the return and the destructuration –namely through its self-referential declension– of the newsreel. In the films of Cohen and George documenting Occupy Wall Street, 15-M, and Nuit Debout, the return of the newsreel highlights the link between the economic structures and the film manifestations, while indicating its dynamic process of formal evolution.

In its ‘state of the form’ (JAMESON, 1992), newsreel’s process of destructuration is pushed to its extreme limits, finding itself in conflict with the background of film forms (newsreel and self-referential cinema’s traditions) as well as with the background of the everyday political experience. Particularly in George’s filmography, this process gives rise to a new structure. Jameson argues that, with the failure of the traditional distinctions between the spheres of work and leisure, to look at images is fundamental to the functioning of most dominant institutions (JAMESON, 2011). Jonathan Crary considers that, under such conditions, ‘most of the historically accumulated understandings of the term ‘“observer” [sic] are destabilized’ (CRARY, 2014: 47). Associating a critical reading of the tradition of avant-garde/experimental and political cinema, political engagement and formal innovation, contemporary newsreels constitute true acts of seeing –affirming image’s productivity– in a network of permanent observation (FOUCAULT, 1993).

Since 2009, the cinematic landscape has been prolific in works that not only constitute film inscriptions of history, visual documents about the emergence of an ‘insurgent citizenship’ (HOLSTON, 2009), and the process of reconfiguration of the public sphere, but that also establish a fertile and transversal dialogue with the history of avant-garde/experimental and political cinema, particularly newsreel. Those film objects interrogate the current state of things –when images become technologies of control– from the point of view of a critical analysis of the dominant forms of visual representation.

Cohen’s Gravity Hill Newsreels (2011) constitute a series of ten newsreels about Occupy Wall Street Movement. The series was conceived to be shown at New York IFC Center Cinema, preceding, as in the past, the screening of a feature film. The political event’s representation is based upon an exploration of the shot/reverse shot’s logic as well as upon contraposition of verticality (architecture) to horizontality (people). Through a virtuous editing and an expressive usage of the music of the ex-Fugazzi Guy Picciotto, Cohen manages to intertwine, opposing them, Manhattan’s architecture and the citizens’ collective movements in an organic narrative innovating newsreel as a film form.

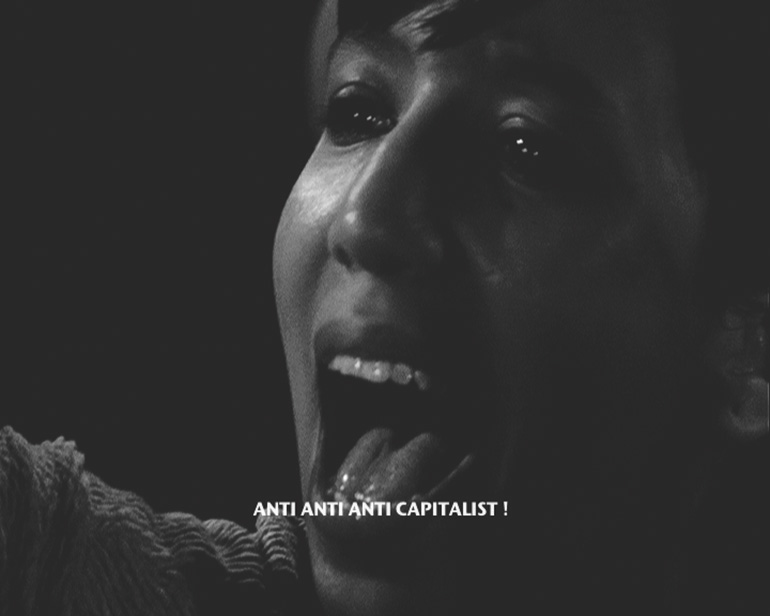

George’s Vers Madrid ! – The Burning Bright (2011-2014) is defined, in its official synopsis, as an ‘experimental newsreel trying to present some political experimentations and new life forms’. It constitutes an aesthetic insurrection manifesto opened upon three different temporalities: first of all, 15-M’s political events in Madrid; secondly, the history of class struggle and the history of avant-garde/experimental and political cinema, evoked both as memory and a matter which is reactivated by the film; finally, the future, it is to say, the almost imperceptible ongoing historical variations and transformations, condensed in dialectical haptic images of radiant lights, sunflowers, undisciplined bodies, and resistant luminescence.

Class struggle and class relations are represented through the collective actions of the social body. In the heterogeneity of its materials, the film summons up multiple literary and cinematographic references, ranging from William Blake (The Burning Bright) to Kramer (its subtitle is Scenes from the Class Struggle and the Revolution evoking Scenes from the Class Struggle in Portugal) to Calderón de la Barca and Federico García Lorca. The low-angle shots, the complex multitemporal sound design, the work of ellipsis, the dialectical organic editing through qualitative, formal and material jumps, which expands and highlights the temporal dimension of the events, the straight and direct cuts that link visually and narratively the individual, the people and the urban architectures where word flows are the main formal traits which allow George to organize a narrative expressive of the complex social confrontation of late capitalism.

Vers Madrid !’s genealogy can be traced back to Soviet Cinema and the different newsreel’s destructuration moments analyzed in this paper. However, a new structure arises from the combination of these procedures with elements from newsreel’s self-referential declension. In some of the film sequences, George is stopped by the police and has to run away. The shaky oblique hand-held camera shots reveal the presence of the filmmaker and his effective and affective involvement in the events. In Paris est une fête – Un film en 18 vagues (2017), George’s most recent film, the documentation of Nuit Debout is intercut with sequences in which the filmmaker’s flâneries become a programmatic variation of the Pasolinian figure of the ‘free indirect subjective’ (PASOLINI, 1991). This mode of cinematic perception and enunciation establishes a system of relationships between visibility’s inside and outside, the possibility and the impossibility to represent ‘reality’, what it is and what might have been, actual and possible worlds. At the same time, it highlights the gap between cinematic representation and natural perception.

Conclusion

This paper aimed to examine the historical and formal evolution of the newsreel as a film form, focusing on its major destructuration moments. Newsreel’s destructuration moments coincide with exceptional political events, such as the Soviet Revolution, the Cuban Revolution, the generalized recession of capitalism economy starting in 1974 (MANDEL, 1974), and contemporary forms of insurrection. The newsreel’s dynamic process of formal evolution points therefore to the link between the economic structures and the film manifestations – a principle which might be applied to the evolution of all film forms. However, this transversal process of permanent mutation shows the capacity of cinema not only to represent, but also to transform ‘reality’. The cases studied in this article point towards ‘form-events’ or ‘film-events’, i.e., film representations which not only represent ‘reality,’ but which also productively transform the history of newsreel, the history of cinema, and general history. Therefore, newsreel’s evolution seems to be produced against the background of film forms as well as against the background of ‘the everyday experience of life’ (JAUSS, 2013), and to have an impact on these two spheres. Within this framework, political cinema involves always formal innovation. Implicit in this definition is the short-circuit of any crude binary opposition between political and avant-garde/experimental cinema.

FOOTNOTES

1 / Unless indicated, all the translations from non-English texts are mine.

2 / In the original, ‘poética interesada’ (‘interested poetics’).

3 / If we consider the conceptions developed in 1859 Introduction to a Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, particularly with regard to ‘the unequal development of material production and, e.g., that of art,’ Marxist position appears as much more complex.

4 / Álvarez devoted two films to the Mozambican Revolution, Maputo: The Ninth Meridian (Maputo: Meridiano Novo, 1976) and Nova Sinfonia (1982).

5 / Álvarez directed a film on Portuguese Revolution, El milagro de la tierra morena (1975).

6 / Jean-Luc Godard’s One plus One is from the same year.

ABSTRACT

Contemporary cinematic representations of the political event (2011-2016) point to an ongoing dynamic dialectic of ‘structuration’ and ‘destructuration’ of the film forms. In the works of Jem Cohen and Sylvain George documenting, respectively, Occupy Wall Street (USA), 15-M (Spain) and, more recently, Nuit Debout (France), the return of the newsreel highlights the link between the economic structures and the film manifestations, while indicating a dynamic process of formal evolution. From the soviet newsreels to the work of Cohen and George, passing by the New Latin American Cinema, and the North-American Newsreel Group, newsreel’s dynamics enables to reconsider, from both a historical and a formal perspective, the relationship between aesthetics and politics, as well as the established distinction between avant-garde/experimental and political cinema. These issues will be examined through the operation notion of ‘form-event,’ which allows to reconcile two dimensions of the aesthetic production: one, which considers art as a reflection; another, which examines it in terms of its outcomes. Newsreel’s formal development from the post-war until the political and cultural contexts in which it has currently evolved brings up a more enriched genealogy of political filmmaking, revealing complex relationships –and a web of influences beyond national film canon– between historical political cinema and the ‘state of the form’ of this cinema.

KEYWORDS

Newsreel, political cinema, avant-garde/experimental cinema, Soviet Cinema, New Latin American Cinema, ICAIC, Newsreel Group, Sylvain George, form-event, aesthetics and politics.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ALTHUSSER, Louis (1973). Pour Marx. Paris: Maspero.

ÁLVAREZ, Santiago (1970). Motivaciones de un aniversario o respuesta inconclusa a un cuestionario que no tiene fin. Pensamiento Crítico, 42, pp. 23-25.

ÁLVAREZ, Santiago (2009). Arte y Compromiso. Miradas de Cine – Tierra en Trance: Reflexiones sobre cine latinoamericano. Retrieved from: http://tierraentrance.miradas.net/2009/03/reviews/escritos-cinematograficos-politicos-de-santiago-alvarez.html [accessed: January 17th 2017]

BREITBART, Eric and Joshua (2001). The Future of the Past. Conversation. VATRICAN, Vincent and VENAIL, Cédric (eds.) (2001). Trajets à travers le cinéma de Robert Kramer (pp. 210-216). Aix-en-Provence: Institut de l’Image.

BRENEZ, Nicole (2011). Edouard de Laurot, Commitment as Prolepsis. Lecture at the Quai Branly Museum, Paris.

Cine Cubano, 140, 1998.

CRARY, Jonathan (2014). 24/7. London and New York: Verso.

DANEY, Serge (1976). L’aquarium (‘Milestones’). Cahiers du Cinéma, 264, pp. 55-59.

DEBORD, Guy and WOLMAN, Gil (2006). Mode d’emploi du détournement. DEBORD, Guy. Œuvres (pp. 221-229). Paris: Gallimard.

DELAHAYE, Michel (1968). La Maison brûle. Entretien avec Robert Kramer. Cahiers du Cinéma, 205, pp. 48-63.

ELIOT, T. S. (2002). Gerontion. In The Waste Land and Other Poems. London: Faber and Faber.

FERRO, Marc (1993). Cinéma et Histoire. Paris: Folio-Gallimard.

FOUCAULT, Michel (1993). Surveiller et punir : Naissance de la prison. Paris: Gallimard.

GARCÍA ESPINOSA, Julio (1979). For an Imperfect Cinema. Jump Cut, 20, pp. 24-26.

GETINO, Octavio and SOLANAS, Fernando E. (2015). Hacia un tercer cine. Apuntes y experiencias para el desarrollo de un cine de liberación en el tercer mundo. Cinéfagos. Retrieved from: http://cinefagos.net/paradigm/index.php/otros-textos/documentos/437-hacia-un-tercer-cine-apuntes-y-experiencias-para-el-desarrollo-de-un-cine-de-liberacion-en-el-tercer-mundo. [accessed: June 25th 2015]

GRAMSCI, Antonio (2012). Guerre de mouvement et guerre de positon. Paris: La Fabrique.

GUERRA, Ruy (2011). Unpublished interview to Raquel Schefer y Catarina Simão. Maputo.

GUTIÉRREZ ALEA, Tomás (1997). The Viewer’s Dialectic. MARTIN, Michael T. (ed.) (1997). New Latin American Cinema, 1, Theory, Practices and Transcontinental Articulations (pp. 108-131). Detroit: Wayne University Press.

HOLSTON, James (2009). Insurgent Citizenship: Disjunctions of Democracy and Modernity in Brazil. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

JAMESON, Fredric (1992). The Geopolitical Aesthetic. Cinema and Space in the World System. Bloomington and Indianapolis, London: Indiana University Press and BFI Publishing.

JAMESON, Fredric (2011). Conferencia en la Film Society del Lincoln Center, New York.

JAUSS, H. R. (2013). Pour une esthétique de la réception. Paris: Gallimard.

KRAMER, Robert (1968-1969). From a series of interviews with Newsreel members. Film Quarterly, 20, 2, pp. 47-48.

LUKÁCS, Georg (1968). Histoire et conscience de classe. Paris: Flammarion.

LUKÁCS, Georg (2012). La théorie du roman. Paris: Gallimard.

MANDEL, Ernest (1974). The Generalized Recession of the International Capitalist Economy. marxists.org. Retrieved from: https://www.marxists.org/archive/mandel/1974/12/generalized_recession.htm. [accessed: January 9th 2017]

MARX, Karl (1977). Le Capital : critique de l’économie politique, 3. Paris: Éditions Sociales.

MARX, Karl (2007). Manuscrits économico-philosophiques de 1844. Paris: Vrin.

MARX, Karl (2008). Introduction à la Critique de l’économie politique. Paris: L’Altiplano.

MICHELSON, Annette (ed.) (1985). Kino-Eye, The Writings of Dziga Vertov. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press.

NICHOLS, Bill (2001). Introduction to Documentary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

NOGUEZ, Dominique (1987). Le cinéma, autrement. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf.

PASOLINI, Pier Paolo (1991). Empirismo eretico. Lingua, letteratura, cinema: le riflessioni et le intuizioni del critico et dell’artista. Milano: Garzanti Editore.

ROCHA, Glauber (2006). Você gosta de Jean-Luc Godard? (Se não, está por fora). In O Século do Cinema (pp. 308-313). São Paulo: Cosac Naify.

ROCHA, Glauber (2015). Estética da Fome. Hambre / Espacio Cine Experimental. Retrieved from: http://hambrecine.com/2013/09/15/eztetyka-da-fome/. [accessed: July 4th 2015]

SCHEFER, Raquel (2015). La Forme-Événement. Le cinéma révolutionnaire mozambicain et le cinéma de Libération, 737 p. Non-published PhD thesis. Paris: Université Paris 3 – Sorbonne Nouvelle.

Vers Madrid ! – The Burning Bright's official synopsis (Sylvain George, 2011-2014).

VERTOV, Dziga (1985a). On the Significance of Newsreel. MICHELSON, Annette (ed.) (1985). Kino-Eye, The Writings of Dziga Vertov (p. 32). Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press.

VERTOV, Dziga (1985b). The Birth of Kino-eye. MICHELSON, Annette (ed.) (1985). Kino-Eye, The Writings of Dziga Vertov (pp. 40-42). Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press.

WOLLEN, Peter (1975). The Two Avant-Gardes. SIMPSON, Philip, UTTERSON, Andrew and SHEPHERDSON, K. J. (eds.), Film Theory: Critical Concepts in Media and Cultural Studies (pp. 127-137). London and New York: Routledge.

XAVIER, Ismail (2007). Sertão Mar : Glauber Rocha e a Estética da Fome. São Paulo: Cosac Naify.

RAQUEL SCHEFER

A researcher, filmmaker and film curator, Raquel Schefer has a Ph.D. in Film and Audiovisual Studies from the Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3 University, with a dissertation on Mozambican revolutionary cinema. She published the book El Autorretrato en el Documental (Self-Portrait in Documentary) in 2008, in Argentina, and book chapters and articles in several countries. She is currently a Teaching Assistant at the University of Grenoble Alpes, and a co-editor of the quarterly of theory and history of cinema La Furia Umana.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

No 9 EZTETYKA

Editorial. Eztetyka

Albert Elduque

DOCUMENTS

Revolution

Jorge Sanjinés

Tricontinental

Glauber Rocha

Godard by Solanas. Solanas by Godard

Jean-Luc Godard and Fernando Solanas

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

A combative cinema with the people. Interview with Bolivian filmmaker Jorge Sanjinés

Cristina Alvares Beskow

Conversation with Eryk Rocha: The legacy of the eternal

Carolina Sourdis (in collaboration with Andrés Pedraza)

The necessary amateur. Cinema, education and politics. Interview with Cezar Migliorin

Albert Elduque

ARTICLES

Reading Latin American Third Cinema manifestos today

Moira Fradinger

From imperfect to popular cinema

Maria Alzuguir Gutierrez

The return of the newsreel (2011-2016) in contemporary cinematic representations of the political event

Raquel Schefer

ImagiNation

José Carlos Avellar

REVIEW

TEN BRINK, Joram and OPPENHEIMER, Joshua (eds.) Killer Images. Documentary Film, Memory and the Performance of Violence

Bruno Hachero Hernández

MONTIEL, Alejandro; MORAL, Javier and CANET, Fernando (coord.) Javier Maqua: más que un cineasta. Volumes 1 and 2

Alan Salvadó Romero