IMAGINATION

José Carlos Avellar

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

This piece was written by José Carlos Avellar (1936-2016) for the exhibition and seminar Tudo é Brasil, organized by Lauro Cavalcanti and produced by Paço Imperial and the Itaú Cultural Institute in Rio de Janeiro between August and October of 2004, and in São Paulo from November 2004 to February 2005. The original version in Portuguese can be found on his web page: www.escrevercinema.com

1.

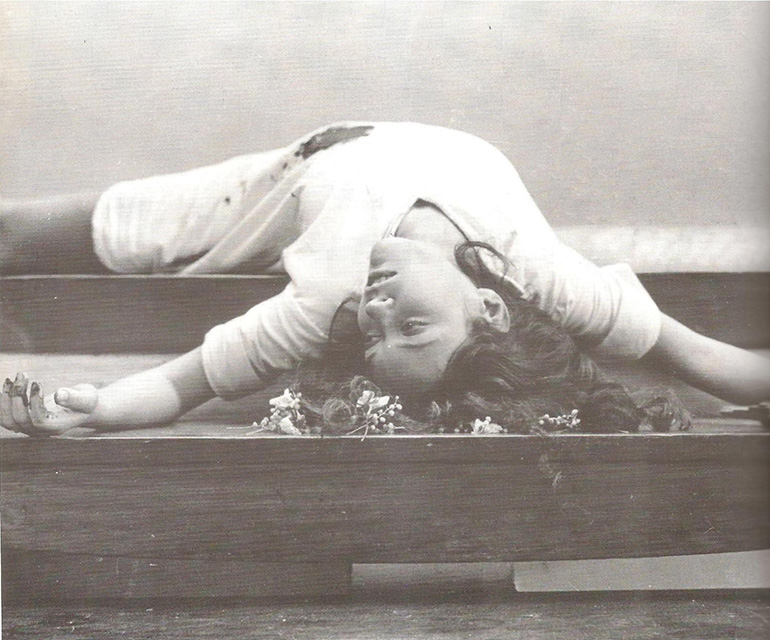

Imagine something that is simultaneously oyster and wind. The oyster, the shell, stagnation, something that is closed and also open to everywhere, something without shape or body, something which is only movement. Let’s consider the title of the film by Walter Lima Jr., The Oyster and the Wind (A Ostra e o Vento, 1996), as if he wanted to refer not only to the characters, to the good relationship between Marcela and Saulo (her being the oyster, him the wind) or the dispute between José and Marcela (him being the oyster, her the wind), but as an image that suggests to the spectator a way to watch the film (or, more generally, a way to watch any and every film). Let’s think about the title as the initial breeze to construct the film; the idea that organizes the story and the way it is narrated. And also, as the expression of an immobility that is highly mobile: the special relationship between the spectator and the film when it is screened. Not the film when the spectator continues to reinvent in his mind what he has seen during the screening, but the film at the moment when there is only image before his eyes. The relationship between the film and the spectator at the moment of screening is one of open/close, movement/immobile. The film (open like air in motion, which gusts everywhere while remaining closed on the screen) is oyster and wind. The spectator (who is still in the projection room like an oyster inside an oyster, and who transports his imagination to everywhere) is both wind and oyster.

2.

Let’s imagine Brazilian cinema in the ‘60s, not exclusively but especially Cinema Novo, as the equivalent of speech. From this standpoint, maybe it is possible to think of current Brazilian cinema as the equivalent of written language, a way of writing the oral language of the ‘60s. What is more, let’s imagine Brazilian films of the ‘60s as the individual speech of each filmmaker, as a result of what we could call a director cinema. From this point, it is perhaps possible to think of cinema before Cinema Novo as a spectator cinema, an attempt to imitate Hollywood’s writing at that time. Maybe it is possible to think of a spectator cinema and a director cinema as basic impulses, not of the idea, but as impulses of the practice of cinema, in particular of the practice of cinema in social groups subordinated by colonization – be it political, economic or cultural. Colonization can be the violence that one nation imposes on another, or which, within a specific country, one sector of society imposes on another. The colonist may have sent in troops or just films, it doesn’t matter. When a group that is economically and materially stronger imposes onto another group, through any kind of pressure, the inhibition that prevents free invention and which conditions people to behave as spectators, then they all become oyster rather than wind, and not just as film spectators.

3.

Maybe when Mário Peixoto directed Limite (1930), he was trying to speak to part of the European photographic avant-garde of the late ‘20s: Moholy-Nagy, Kertész, Burchartz, Man Ray, Hausmann, Renger-Patzsch and Rodtchenko. Maybe when Humberto Maure directed Ganga Bruta (1933), he was trying to talk to another sector of the European photographic avant-garde: Cartier-Bresson, August Sander and Alfred Stieglitz. It was a conversation that was direct and conscious, or mediated by any other image, in a magazine or a film, influenced by them, because maybe Peixoto and Mauro were indeed engaged in a dialogue in the general belief that cinema allows us to watch more, and better. Then Vertov spoke of the possibility of ‘making visible the invisible, of lighting the darkness, of watching without limits and without distances’. Then Grierson spoke of the possibility of ‘observing and choosing moments of life itself to create a new art’. Mauro, in a dialogue with Grierson, tried to bring to Brazilians a more accurate version of ourselves on the screen – to bring ‘our environment, our land, nation, Brazil as it is’ to cinema. Peixoto, in a dialogue with Vertov, tried to show that cinema makes us watch less and worse; it makes invisible what is visible, and herein lies its strength. What can be seen is shown just to establish a tension with what cannot be seen. Cinema covers, it hides and cuts. It actually starts with a cut, as if the commanding voice that interrupts the shot – ‘Cut!’ – marked the beginning of it all. Maybe we can photograph ourselves as a part (not as a whole), a photo taken before digital photography and which, before our very eyes, extends for an infinite time the process of developing, the photographic paper in the developer, the image is formed and at the same time it is modified by a tiny beam of light. Maybe we reveal ourselves in the same way that Walter Lima Jr. observed in a statement in the first issue of the magazine Cinemais (September/October, 1996):

‘It is significant that within Brazilian cinema there are two films that are such clear archetypes of our research: Limite and Ganga Bruta. Something you have to refine and something that determines your space, while suggesting that it exists beyond itself. This is strange, but in a way it creates a parameter’ (MATTOS et al., 1996).

4.

Let’s imagine that this issue can be considered at the same time as an oyster (everything is Brazil) and wind (Brazil is everything).

5.

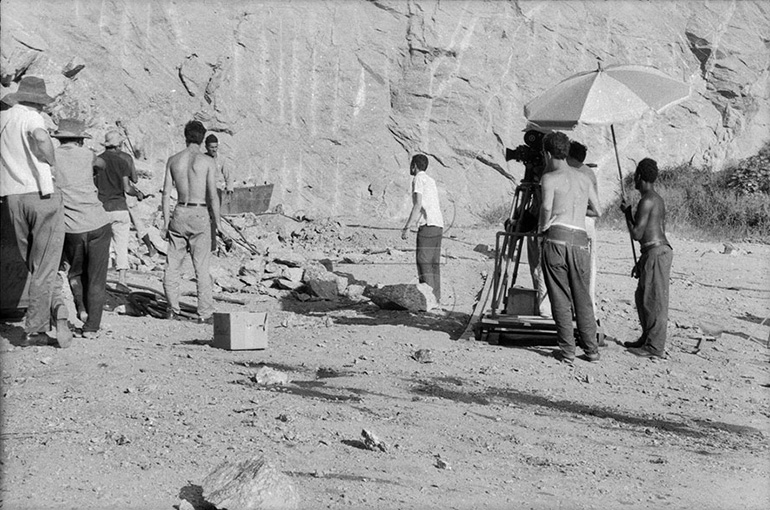

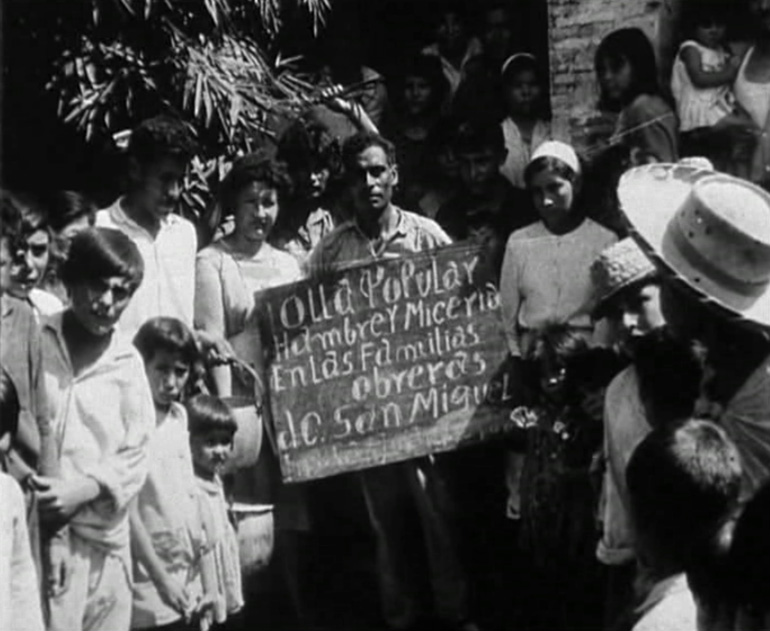

Let’s imagine that not everything that is ours belongs to us, and that we do not wish to own a part of what is ours. As Nelson Pereira dos Santos stated in a conversation with Maria Rita Galvão about Vera Cruz (1981): ‘We wanted a cinema that reflected the Brazilian reality, as if it was possible to make a cinema that didn’t reflect it, that wasn’t related to the reality that originated it. As if Vera Cruz itself wasn’t the reflection of a thousand things’. A line by Zavattini (as Nelson said: ‘We didn’t look for support in its idea system, but rather in sentences’): ‘Cinema has to look for truth, poetry comes after that’. An image of Eisenstein (as Leon Hirszman said: ‘I saw Potemkin and I went crazy! I thought I was watching the Renaissance, you know?’). Let’s remember: The Grand Moment (O Grande Momento, 1958) by Roberto Santos; Pedreira de São Diogo (1962) by Hirszman. Let’s imagine: Zavattini and Eisenstein as samba, readiness and other bossas. Vera Cruz, our thing?1

6.

Let’s imagine that Brazilian films, beyond the stories told in each of them, all say together that we possess a fragmented vision of ourselves. Maybe cinema, maybe even the country as a whole, undergoes a similar process to the one in the documentary O Fio da Memória (1991), presented by Eduardo Coutinho as a condition imposed onto black culture: following abolition, black people – illiterate, uncultured, without citizenship and without a family – had to fight against disintegration, gather all the pieces of their identity, and to build ‘the Brazil according to ourself2’, as Gabriel Joaquim dos Santos wrote in his diary. He lived in the town of São Pedro d’Aldeia, less than 200 kilometers away from Rio de Janeiro. He built his house there, the Casa da Flor, using objects he picked out of the garbage – pieces of glass, broken tiles, pieces of brick, stone or wood – and regularly wrote down fragments of life in Brazil in his notebooks from the moment he learned to read, when he was 34 years old, in 1926, until his death in 1985, at the age of 92. Let’s imagine that Brazilian films tell stories with similar eyes to those of Gabriel, stubbornly wanting to build a house, a place, a country.

7.

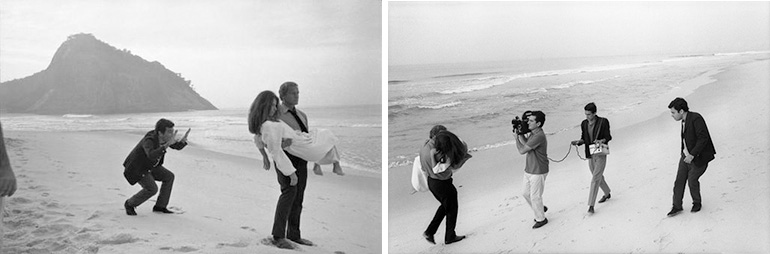

Let’s imagine a foreign spectator. Foreign not because, by chance, he is not in the country where he was born, but because he has the condition of a foreigner; or because he is surviving outside the space where he could be fulfilled; or because the conditions by which he received a news bulletin, or a soap opera, or a film on television turned him into a distracted spectator, and he is always foreign to the picture in front of him. When, in the adventure in Foreign Land (Terra Estrangeira, 1996) by Walter Salles and Daniela Thomas, Brazilian Alex, who has emigrated from Brazil to Portugal, sells her passport (nowadays a Brazilian passport is worth nothing, says the buyer), or when she says she feels sorry for the Portuguese (because they crossed the ocean with great effort just to discover Brazil) – when she acts and talks like that, Alex is not just behaving according to the context of the plot of the film. She is also (and mainly) expressing dramatically the feeling that engulfed Brazilian middle-class youngsters at the beginning of the ‘90s. The adventure on the screen experiences in another dimension what the spectators really experienced: the sense of belonging to a country that doesn’t work, of lacking roots or identity, of feeling that their land is foreign, of surviving (let’s remember two moments in the film) like a ship beached on a sand bank, like a car speeding to cross the border.

8.

Let’s imagine that thinking about art as an expression of a certain reality means thinking, at the same time, about reality as an artistic expression, or rather (not to imagine too much), thinking of art as the possibility of foreseeing a certain fact and expressing a reality that still doesn’t exist.

9.

Let’s imagine that when Joaquim Pedro de Andrade said in 1966, in an interview for O processo do Cinema Novo by Alex Viany (2001), that ‘There is always a layer of interpenetration, of communication, between the intelligence of developed countries and ours, of less developed countries’, he was searching not for a dialogue with the European or North American avant-garde, but rather with Latin American expression at that time. Together with Solanas, ‘The underdeveloped countries are victims of a neocolonialism in which the standardization of cultural models substitutes the occupation armies’; Glauber, ‘An economically underdeveloped cinema should not be culturally underdeveloped’; and with Nelson Pereira dos Santos, ‘We suggest making a cinema that is free from the limitations of the studio, a street cinema that is directly in contact with the people and their troubles’. When Joaquim says that nobody can avoid ‘receiving information from the world’s cultural avant-garde’ and being ‘obviously reached by this information’, he continues with the discussion of that time: how can we reject ‘directly imported values and processes that are not really connected to our reality’? How can we ‘find the genuine Brazilian processes’? Joaquim recalls the attempt to adopt an approach to this problem at the Week of Modern Art, and says: ‘We would gain a lot if we analyzed the Movement of 1922 once again in relation to what is happening now’.

10.

Maybe, close-up (like an oyster) on O Cangaceiro (1953), the radical statements (rather than wind, gale) of Lima Barreto and Glauber could be understood as a suggestion that the solution for what is ours is in what is ours, in the Brazil made by ourself3, (‘Whoever thinks otherwise is dumb and unpatriotic’), and that our problem is the difficulty of finding what is ours (‘Who are we? Which is our cinema?’). In a letter written in 1954 to O Estado de São Paulo (quoted by Alex Viany in Introdução ao cinema brasileiro, 1959), Lima Barreto says that ‘If we admit there should be, and should happen, a Brazilian contribution to international cinema-art, it is with the content of films, rather than with the technical external form. In the case of Brazilian cinema, and in defense of our culture, representation should be more important than presentation. Generally, the fools in cinema, the dull people in cinematographic art, are left speechless before a limpid image, an audible sound, a slightly strange montage, a Dutch angle. They are not interested in whatever is behind all this – the essence, the real intention of the film, the message, the filmologic intention; they do not see this, they do not even suspect that it exists. The presentation technique, the external look of cinema, the container of filmology, black-and-white or color cinematography, stereo or not stereo sound, sumptuous scenery or adjusted to the action, Cinemascope, the third dimension, VistaVision, the sometimes miraculous tricks, the make-up, the extravagant camera movements – these have all been pushed to the limits in gringo cinema. And, while we do not discover our themes to express them within our own aesthetic-film-cinematographic concept, eminently lower-class-peasant-mestizo-farmer-rustic4, as Mário de Andrade and the few cultured men in Brazil would like, we will not find the audiovisual way to generalize, to spread our culture, which is incipient, yes, but it is also authentic, real, irrefutable. Whoever thinks otherwise is dumb and unpatriotic’.

Maybe we can say that when Glauber was discussing O Cangaceiro in Revisão crítica do cinema brasileiro (Critical revision of Brazilian cinema,1963), moved by the idea of Black God, White Devil (Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol, 1964), which was being shot at that time, he saw Lima Barreto at the same time as ‘atheist and Catholic, patriotic and reactionary, progressive and developmentalist, neither on the right nor on the left wing’, ‘a Parnassian loaded with a lot of very badly-interpreted information’; as the director of a film addressed to a spectator who is ‘educated in the idealist mythology of a Western movie’ and who cannot ‘place the cangaçao, as a mystic-anarchic rebellious phenomenon that emerged from the landowner-based system in the North East, worsened by the droughts’. In Glauber’s opinion, Lima, ‘having failed to understand the novel of cangaçao and to interpret the meaning of the popular novels of the North East’, made ‘a psychologically primitive and conventional adventure drama’, an ‘epopee with the rhythm of a Mexican corrido’. However, behind the radical disagreement, both texts seem to agree that the Brazilian contribution to cinema is ‘in the content of films rather than in their external technical form’ (as Lima Barreto said in his letter) because ‘a technical ability should not be the support for an expression like cinema’ (as Glauber said in his Revisão).

11.

Let’s imagine that the spectator watching a piece of art is before a product of a process that has undergone a contemplative act of the objective reality, as Tomás Gutiérrez Alea suggested in his Dialética del espectador (Dialectics of the spectator, 1982); that a piece of art is not addressed exclusively, but mainly, to a privileged spectator, and that it tries to illuminate through a dialogue with this otherness; if that is so, we can imply that in a certain step of the invention process of a work, the director, as a spectator in the contemplative act, will favor a certain work as a piece of the objective reality that will illuminate his creation; therefore the matter does not lie in the relationship with the other, but in the choice of the other. What is more, let’s imagine, as Hélio Oiticica suggested in Situações da vanguarda no Brasil (Situations of the avant-garde in Brazil,1966), that ‘We are over the matter of the objective of art, we are past that phase’, and that the artist has to ‘offer a way to provide the possibility to experiment creation, to let the spectator turn into a participant’. Let’s imagine art as something that transforms the spectator into a creator, an invitation to creation as suggested by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino in The Hour of Furnaces (La hora de los hornos, 1968). This film recalls what Frantz Fanon said in 1961 in The Wretched of the Earth (Les Damnés de la Terre): (in the fight against colonialism nobody can run away) every spectator is either a coward or a traitor. The invitation to think like Alea (remembering Marx: the production of a piece of art does not just make an object for a subject, but also a subject for an object): director and spectator is all the same thing.

12.

Let’s imagine that the issue summarized at some point by Glauber with two questions – Who are we? Which is our cinema? – is not the question, but the answer. Let’s imagine we are a question.

13.

Let’s imagine a not-articulated expression, like a speech is articulated in writing: the opening images of Barren Lives (Vidas Secas, 1963), by Nelson Pereira dos Santos, are like this, they are trembling and almost entirely white. Long shots, almost empty, white on white, camera hand-held by the operator who walks alongside a family of emigrants; the images flow onto the screen like thoughts in construction spoken aloud, a visual correspondence of the word: of the more accentuated pronunciation of a word and the half-swallowed sound of another one in the middle of the sentence; of the gestures that go with the speech and which complete the meaning of what is only half said, and of the sometimes-irregular punctuation, of the pauses that show the search for the correct expression. In short, the intense white and the trembling image can be viewed as correspondences of all the imperfections of spoken language when compared to the written language. Let’s imagine a little further, a speech that is not very well organized as a language, an essential and rudimentary phenomenon, pure expression, completely inarticulated: the images of Black God, White Devil by Glauber are like this, those images in which the camera rises, as if it was on its knees, next to the parishioners of Sebastião, the stones in Monte Santo; the other images around Corisco or running alongside Antônio das Mortes. Neither a foreign and unknown language nor a deliberate misarticulation caused by the misuse of the language: we are talking here as if there was no language, as if everything was to be invented, as if a new way of feeling and thinking about the world was being invented at that moment, as if there was a word that had never been said before. To simplify everything: let’s think about language as a cinema resulting from the montage of two different shots which are sometimes apparently in conflict with each other but which are actually complementary: speech and writing. The first is natural, open, like a shot in a documentary. The second is disciplined and constructed like a shot in a feature film. Let’s think of the cinema of the ‘60s as an equivalent of speech, not because it tried to visually show the oral language of Brazilians, not because it tried a similar operation to when a film is supported by written language to structure its narrative. In the ‘60s, cinema was speech rather than writing because it was expressed through lively and partially articulated oral language; because it was even expressed with the equivalents of (shall we say) word before word, with the equivalents of the moment in which, to express anything even before it had a name, there is only an interjection, a shout, a grunt, a silent gesture, a speech that comes from feeling rather than reason. Let’s imagine: reality was then felt as cinema in nature. Life in its entirety, ‘its actions as a whole, is a natural and live cinema, and that is linguistically equivalent to oral language’. With memory and dreams as ‘fundamental outlines’, cinema represents ‘the written moment of this natural and total language, which is the action of men in reality’. Pasolini then imagined cinema as the written language of reality. In a dialogue with this way of feeling reality as a cinema in nature, Cinema Novo was considered an oral, natural and total language, action in reality, almost as if there was no film on the screen, representation as a re-presentation/reinvention of reality, as a first language. Indeed, first: thought being articulated, thought in the desert, on the border, in the moment between the still not-conscious, the still not-present, and the possibility of gaining form and expression.

14.

Let’s imagine that making cinema among us was like dictating a letter for Dora in Central Station (Central do Brasil, Walter Salles, 1998): the chances that the letter will be taken to the post office and reach the addressee are low. And the chances that Dora, even though she has decided to take the unlikely decision to bring the letter to the post office, will find any postmen interested in delivering domestic post are also very low. For the postmen in cinema, the letter is also coming from outside, it is written in another language and has a different kind of stamp. Let’s imagine that the free cinematographic imagination can sometimes be confused with the dubbing in Portuguese on foreign films, as recounted in Better Days Ahead (Dias Melhores Virão, 1990), by Carlos Diegues, in which the brunette Brazilian dubber sees the blonde American actress on TV with her voice and says: ‘Look, I’m on television!’.

15.

Let’s imagine what Nelson Pereira dos Santos once said to sum up the feeling that motivated his generation in the mid ‘50s – ‘We didn’t just want cinema, we wanted Brazilian cinema’ – as an expression addressed not to foreign cinema, but to films being made at that time, adaptations of foreign trends. He explained in declarations to Maria Rita Galvão for Burguesia e Cinema: o caso Vera Cruz (Bourgeoisie and Cinema: the case Vera Cruz) what was being discussed at the time: ‘We tried to copy international cinema, its dramatic structure, its language, its themes, everything [...]. For example, there weren’t any black people in films except for in certain roles, which were stereotyped as black, like Ruth de Souza, who always played the maid. This was a prejudice, black people were considered from white, rich people’s point of view. It was a characteristic of American cinema brought into Brazilian cinema. In the USA, black and white people lived in separate worlds, but here they did not, their interrelation was much greater, even if prejudices did exist, and there were also a lot of skin-bleached mulattos living among white people. But not in films. Even the actors’ appearance was Americanized. Girls were wearing American-style make-up, many actors had their hair dyed in lighter colors. That sort of behavior was not our own, it was unnatural for us, even if it was (at least, I think it was) natural in American films. Etc. The use of Portuguese in Paulista cinema was senseless, it was completely false; there was a prejudice against using the usual, wrong, oral language in films, which is in fact our language. We often make mistakes when speaking, I do, you do, and yet we have both benefited from higher education... But if this is how people speak, then why is it wrong?’ One thing was clear: ‘cinema did not express our reality, it did not have cultural representation’. In order to give it representation, we had to ‘create our own expression and stop using a preexistent expression, like Vera Cruz did’.

16.

Maybe when Júlio Bressane restated, in the ‘90s (shortly before his Miramar [1997]), that cinema ‘is an overly sensitive intellectual organism, not just sensitive, but over-sensitive’ and that this excess ‘pushes, forces cinema to find its limits’, to create ‘a border with all the arts and with almost all the sciences’, with this statement he seems to continue and expand what Mário de Andrade said in the ‘20s (shortly before his ‘cinematographic novel’, Amar, verbo intransitivo [To Love, Intransitive Verb, 1927]): cinema, as an impure art, is ‘the eureka! of pure arts’. Impurity, mixture, multiplicity of languages, art felt as the process of editing varied and different materials and influences. Maybe the influence that cinema had on pure arts at the beginning of the Twentieth Century is similar to the influence television now has on cinema. By mixing – with an even greater impurity – theater, music, literature and cinema lessons, television has developed a way of communicating that leads to the spectator paying little attention to the image, focusing instead on the interests of television and himself. Television tries to fragment and repeat what it shows to make the conversation easier to follow; the spectator tries to watch television while watching and doing other things, free from the focused, exclusive attention he devotes to a cinema screen. While once, when he was watching a film by the Lumière brothers in which the La Ciotat train looked as if it was about to jump off the screen into the room, a spectator closed his eyes, turned his face away and even seemed about to run out of the room, nowadays it doesn’t matter what kind of nightmare is threatening to jump out of the television into the house, the spectator will keep his eyes open, but he’s not focusing his attention anywhere. He tries to defend himself from what he is watching without ceasing to watch it. With a television in the living room, being at home is like being outside home at the same time, being somewhere else, where you can behave like Ninhinha in The Third Bank of the River (A Terceira Margem do Rio, 1995) by Nelson Pereira dos Santos: in order to fulfill her grandma’s wish, she puts her hand inside the image on the television and brings the box of chocolates into the living room. The house as this other place, no-man’s land, in no way reality; and also the image, from time to time stretches its hand out of the television to take something. Sitting in front of the television, the spectator can repeat to himself what Portuguese Pedro says to Brazilian Paco when he has just arrived in Lisbon in Foreign Land: ‘This is a place to meet nobody. It is the perfect place to lose someone or to lose oneself’.

17.

Let’s imagine that before the ‘60s we tried to write before we learned to talk, as if a language could be born first as writing only to emerge as speech, or that we tried to write the cinema that was spoken in Hollywood. Barren Lives and Black God, White Devil appear at a time when cinema was made like a drawing of an idea that is thought of before the image, thought in writing – and sometimes thought by somebody else, thought outside, where, it seemed, they thought better. Let’s imagine then that cinema was thought of as a way to coordinate a limited range of possibilities for composing images (close-up, long shot, high-angle shot, low-angle shot, shot / reverse shot, tracking shot, travelling, tilting): the image achieved with a hand-held camera (all these shots and none of them at the same time) and the improvisations during the shooting were the strengths of our films in the ‘60s. Actually, shooting like that, revealing the nervous presence of the camera rather than the actual scene, was a creative operation to make the cinematographic language more complex. Land in Anguish (Terra em Transe, 1967), by Glauber, is a good example: the scene is improvised, not because it was not thought about when writing the script, but because it was still being thought about during the shooting. The image was trembling not because the operator was lacking in camera skills, but because at that time reality was being discussed in this way, in a nervous, trembling discourse. Then cinema thought about the script as a challenge to shooting, shooting as a challenge to editing and the film as a challenge to the way of seeing. Cinema was considered an expression that is finished, ready, on the screen, and at the same time unfinished; part of a process that does not end with shooting: image-provoking, rushes, work print so that the spectator can clean out and order everything in his imagination.

18.

Let’s imagine that this issue can be considered at the same time as an oyster (Brazil is everything) and wind (everything is Brazil).

19.

Let’s imagine an image that is interested not just in revealing who watches it, but also in the way the spectator watches. Let’s see, for example, the story of the retired teacher who, in order to make a living, writes letters for people who can’t read, as if she was a metaphor for the process of renaissance of Brazilian cinema after the standstill imposed by the corruption of the Collor Government between 1990 and 1993. Central Station was not created to serve as this metaphor, but it can also (once its essence is understood) be viewed thus, as the story of the renaissance of looking: we could tell stories once again in a language that is common to us all and is our own; we could rediscover the country, discover ourselves as part of a certain space and time. The film runs through landscapes and characters that marked the oral cinema of the ‘60s: the North West, the sertão, the emigrants, the pilgrims, the ordinary workers in the suburbs of the big cities; it follows in the other direction the migration of the characters in Barren Lives, it follows the journey of a woman who is undergoing a process of resensitization. The expression used by Walter Salles defines the experience of Dora and, by extension, of Brazilian cinema in recent years. The films and the audiences, cinema as a whole, have all undergone a process of resensitization. This process is in a way a reencounter with the father (the old Cinema Novo, and through it a reencounter with everything it was in dialogue with) and with the country. It is the understanding of a country which to some extent resembles the protective, castrating father in The Oyster and the Wind; it proceeds on to the impotent authoritarian man who takes paternal possession of children who are not his own in Me You Them (Eu, Tu, Eles, 2000) by Andrucha Waddington; then on to the insensitivity of the father who confines his son to a hospice to get away from the embarrassment of seeing him taking drugs in Brainstorm (Bicho de Sete Cabeças, 2001) by Laís Bodanzky; on to the tragic figure of Tonho and Pacu’s father in Behind the Sun (Abril Despedaçado, 2001) by Walter Salles; and to the absence of Branquinha and Japa’s father in How Angels Are Born (Como Nascem os Anjos, 1996) by Murilo Salles; and to the absence of the father in Central Station.

The reencounter with the father/country5 is created with all the ambiguity and tragedy that the story of Dora and Josué gives to the figure of the father, which is at the same time the figure that Josué admires without knowing him, that Moisés despises because he destroyed himself with drinking and that Isaías is hoping to see when he comes back home to his family and to work with wood. Dora does not forget that he is a rude, insensitive drunkard who abandoned his family and once tried to seduce his own daughter when he met her in the street without recognizing her; but Dora ends up remembering that one day he let his daughter, who was still a child, drive the train he was working in. The reencounter also represents the regaining of a way of looking that is determined to invent the country through cinema – or vice versa, because the invention of one would be the invention of the other: creating a picture that can express the country would be like creating cinema and then the country in its own image and likeness, national image.

20.

Let’s imagine that the issue can be considered through this scenario: Marcela (oyster?) is kept prisoner in the island by her oppressive father, as if she was the sister of Josué (wind?), who goes across the country from the South West to the North East searching for the father he has not met yet.

21.

Let’s imagine that what is ours as a solution for what is ours could also go beyond our borders. This is what Alex Viany seems to be suggesting in the opening page of his Introdução ao cinema brasileiro (Introduction to Brazilian cinema, 1959), when he includes a line by Noel Rosa from 1930 (‘The samba, the readiness and other bossas are our things, are things from us’6) next to a sentence by Álvaro Lins from 1956: ‘We can’t afford the luxury of being “citizens of the world” because we aren’t men enough of our region and our country; that is, men properly imbued with the feeling of the land, of society, of Brazilian culture’, and ‘we can’t aspire to achieve an international position until we have strengthened our national position. Both in art and in politics’. What is more, in the first part of the quote, he stresses: ‘It is necessary to make nationalism in literature and art. Emancipating culturally, in the same way we talk of economic emancipation. We need to think of Brazil in terms of nation and in terms of America, especially South America’. Latin America as what is ours: in 1959, Glauber sees the Mexican film Roots (Raíces, 1953) by Benito Alazraki as a contribution ‘to the future of cinematographic language in Mexico, in Latin countries and mainly in Argentina and Brazil’; in 1961, while in Salvador, even before finishing Barravento (1962), Glauber suggests in a letter to Alfredo Guevara from the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC) that an international meeting of Latin American independent filmmakers should be held, to show films and discuss common problems; in 1967, in Viña del Mar, Chile, the first Latin American filmmakers’ meeting takes place; impure and contradictory art which, as it is too sensitive, borders on everything. Cinema was starting to suggest the image of a nation, an extension of what is ours: ‘the notion of Latin American is bigger than the notion of nationalisms’. The other, the avant-garde, the interlocutor, what is ours made by ourself7 was right here or right beside us.

22.

Maybe with the same words, the same statements, and even the influences of the same films and texts for the invention of a Brazilian cinema, the directors were referring to different things at the beginning of the ‘50s (could we say that they were looking for a formula?) and at the beginning of the ‘60s (could we say that they were looking for a process?). The mixture of German expressionism (intense light favors a point in the scene) with Italian neorealism (soft light spread all over the scene) in O Cangaceiro by Lima Barreto or in The Given Word (O Pagador de Promessas [1962]) by Anselmo Duarte. The mixture of neorealist image captured in natural sets with the landscape of Rio, in Agulha no Palheiro (1952), by Alex Viany, and Rio 40 Graus (1955) by Nelson Pereira dos Santos, and with the landscape of São Paulo in The Grand Moment. Maybe we can see, in these mixtures, the beginning of a new relationship in which foreign cinema ceases to be a model and becomes an interlocutor. A goodbye to parodies (an example: Nem Sansão nem Dalila [1954] by Carlos Manga instead of Samson and Delilah [1949] by Cecil B. De Mille). A goodbye to imitations of European and North American styles and genres (an example: The Drunkard [O Ébrio, 1946] by Gilda de Abreu, instead of The Lost Weekend [1945] by Billy Wilder. A few more: Walter Hugo Khoury, O Estranho Encontro [1958], instead of Bergman; Rubem Biáfora, Ravina [1959], instead of Wyler). An interlocutor: in the same way that in 1969 an open and informal seminar was held in which Hirszman, Joaquim, Escorel, Sarno and David Neves, among others, took part, and Glauber reinvented Eisenstein by reading and discussing his theoretical work.

23.

Let’s imagine: maybe we do not imagine as much as we should. What Time magazine wrote on the 26th of April of 1999 when it announced the release of Star Wars: Episode 1 – The Phantom Menace, by George Lucas, represents for us, rather than a threat, a real and immediate danger: today, everything we can dream of can be achieved by digital technology in cinema: ‘If you can dream it, you can see it’. Something is not right in our dreams if we only dream what can be quickly achieved. By placing technology above our ability to dream, the magazine is just repeating Hollywood’s main promotional strategy, it is reaffirming the common feeling that technology thinks, imagines and makes for us. In the world of technological expression, avant-garde seems to be left behind – that is why, as Cláudio Assis said, he, Lírio Ferreira and others formed an artistic group called Vanretro, the Vanguarda Retrógrada (the Backward Avant-garde) while they were at university in Recife. Films produced by the big audiovisual industry, beyond the stories they tell, confirm that what really matters is technology, and that everything that can be imagined has already been imagined.

In this context, it is not difficult to imagine what we have to do: let’s imagine.

FOOTNOTES

1 / The author is talking here about the famous samba song by Noel Rosa ‘São Coisas Nosas’. The chorus goes: ‘O samba, a prontidão / e outras bossas, / são nossas coisas, / são coisas nossas!”. The translation in English would be: ‘The samba, the readiness / and other bossas / are our things, / are things from us’. ‘Bossa’ is a difficult word to translate in this context, because it means, among other things: convex architectural decorations, a vocation or talent, the way the body moves when walking and a way of doing things.

2 / Grammatical disagreement in the original: ‘nós própio’.

4 / The original text uses a few Brazilian words that are difficult to translate: ‘matuto-caipira-caboclo-campeiro-sertanejo’.

5 / Wordplay in the original: ‘pai/país’.

ABSTRACT

In this piece written in 2004, José Carlos Avellar explores the emergence of Cinema Novo in the ‘60s and its legacy for Brazilian films in the ‘90s, especially The Oyster and the Wind (Walter Lima Jr., 1996) and Central Station (Walter Salles, 1998). To that end, the author considers the metaphor of speech/writing to suggest that the movement possessed the creative spontaneity of oral language; the search for a cinematographic identity, in relation to the national culture, the New Latin American Cinema and European and US cinema; and, finally, the attitude of the spectator when faced with images which, according to him, should never undermine his ability to imagine.

KEYWORDS

Cinema Novo, New Latin American Cinema, The Oyster and the Wind, Central Station, brazilian cinema, cinematographic writing, spectator, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, Glauber Rocha, Walter Lima Jr.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ANDRADE, Mário de (1927). Amar, verbo intransitivo: Idilio. São Paulo: Casa Ed Antonio Tisi.

FANON, Frantz (1961). Les Damnés de la Terre. Paris: La Découverte.

GALVÃO, Maria Rita (1981). Burguesia e cinema: o caso Vera Cruz. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Civilização Brasileira, Embrafilme.

GUTIÉRREZ ALEA, Tomás (1982). Dialéctica del espectador. La Havana: Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba.

MATTOS, Carlos Alberto de, SARNO, Geraldo, BENTES, Ivana, AVELLAR, José Carlos (1996) Walter Lima Junior: reinventar a luz, com alguma originalidade. Cinemais, Vol. 1, September-October 1996, pp. 7-30.

OITICICA, Hélio (1966). Situação da Vanguarda no Brasil. FIGUEIREDO, Luciano, PAPE, Lygia, SALOMÃO, Waly (orgs.) (1986). Aspiro ao Grande Labirinto. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco.

PASOLINI, Pier Paolo (1995) Empirismo eretico. Milano: Garzanti.

ROCHA, Glauber (1963). Revisão crítica do cinema brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Civilização Brasileira.

VIANY, Alex (1959). Introdução ao cinema brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Nacional do Livro.

VIANY, Alex (2001). O processo do Cinema Novo. Rio de Janeiro: Aeroplano Editora.

JOSÉ CARLOS AVELLAR

José Carlos Avellar (1936-2016) was one of the main theorists of Brazilian and Latin America cinema. He was a critic for the newspaper Jornal do Brasil for more than twenty years and wrote reference books such as O Cinema Dilacerado (1986), A ponte clandestina – Teorias de cinema na América Latina (1995), Glauber Rocha (2002) and O chão da palavra: Cinema e literatura no Brasil (2007). Throughout his life, he also held different positions in institutions linked to cinema, including director of the film archive of the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro (1991-1992), director-president of RioFilme (1994-2000), president of the board of the Petrobras Cinema program (2001-2009) and vice president of FIPRESCI (1986-1995).

No 9 EZTETYKA

Editorial. Eztetyka

Albert Elduque

DOCUMENTS

Revolution

Jorge Sanjinés

Tricontinental

Glauber Rocha

Godard by Solanas. Solanas by Godard

Jean-Luc Godard and Fernando Solanas

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

A combative cinema with the people. Interview with Bolivian filmmaker Jorge Sanjinés

Cristina Alvares Beskow

Conversation with Eryk Rocha: The legacy of the eternal

Carolina Sourdis (in collaboration with Andrés Pedraza)

The necessary amateur. Cinema, education and politics. Interview with Cezar Migliorin

Albert Elduque

ARTICLES

Reading Latin American Third Cinema manifestos today

Moira Fradinger

From imperfect to popular cinema

Maria Alzuguir Gutierrez

The return of the newsreel (2011-2016) in contemporary cinematic representations of the political event

Raquel Schefer

ImagiNation

José Carlos Avellar

REVIEW

TEN BRINK, Joram and OPPENHEIMER, Joshua (eds.) Killer Images. Documentary Film, Memory and the Performance of Violence

Bruno Hachero Hernández

MONTIEL, Alejandro; MORAL, Javier and CANET, Fernando (coord.) Javier Maqua: más que un cineasta. Volumes 1 and 2

Alan Salvadó Romero