VOICES AT THE ALTAR OF MOURNING: CHALLENGES, AFFLICTION

Alfonso Crespo

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / ENDNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / ENDNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Cinema, as both Daney1 and Rivette2 could corroborate, always has to wrestle with the cumulative erosion of innocence and potency. Always a little less innocent, always a little less potent. There is no way back; there is no door, Thomas Wolfe would say; we can’t go home again, Nicholas Ray would tell us. With the arrival of sound, the first loss was identified: “silent film”, along with the burial of the first utopias associated with the invention of the machine, the ones that modern filmmakers later attempted to revive once the conventions of the “talkie” had already imposed the law of survival of the fittest. Too late, as is well-known, because those who believed they were next were actually last. As Rancière suggests (2011: 42-43), the build-up of banality that sound brought with it and the evident betrayal of cinema’s original mission –to show and relate phenomena– fed Godard’s redemptive grieving in his Histoire(s) du cinema (1988-1998), where, in the style of Cocteau, he attempts a return, a rewind, in order to imagine retrospectively a different scenario from so much squandered fascination, now that the tension of the time when it was thought that cinema would transform the world is long gone, bringing ruins back to life, making “Vertov with icons extracted from Hitchcock, Lang, Eisenstein or Rossellini.” And if the achronological feat of wistful restitution that is Histoire(s) is possible and proves so powerful it is because Godard, who in his day turned the camera frame into a blackboard and even negated himself in it, to give free rein to the rivalry between visual track and audio track, knows the secret that the advent of sound brought with it, a secret subsequently concealed behind the wearying rally of shot-reverse shot and dialogue responses: the emergence of the voice and the disjunctive synthesis that it could provoke with the parade of images. This was the gift that was given in exchange for the irremediable loss, a Meccano kit without instructions whose seller claimed that other means could be used to recreate the mystery of hallucination of life and the glimpse of the invisible through the observable. In this ersatz product more than a few hopes have been placed, and there have been many, including many prominent figures who, since the dawn of sound and its contrapuntal theories, have suggested that it was there, in the possibilities opened up by asynchrony and the aimless freedom of words and images, where we could find the true specificity of cinema, its power as a producer of meaning and a stimulator of imaginaries.

At its core, even in its most anti-natural and forced application (i.e., the use of synchrony), the combined presence in film of images and voices –of reflections seen and words heard– introduced the ghost of a non-relationship from the outset. Thus, for example, it was theorists like Balázs –for whom there was a chasm rather than a break in continuity between silent and sound film, if they weren’t in fact two different art forms (1945: 241)– who celebrated the use of the voice-over/off as a strategy that could give the image back at least a shadow of the autonomy it had enjoyed in the silent film era, as this should not have been compromised by the narrative intelligibility that had now fallen upon the word. Spectators could thus once again lose themselves in the images. But this aperture, this interstice between soundtrack and visual track would be explored in depth by only a few, a select and elusive sect, it might be said, the only ones who have given meaning to the expression “audiovisual”, those who located sound and image on either side of a chasm. I refer here to stellar moments in film history, with repercussions on the history of ideas and thought. Thus, when Deleuze (1985: 159-190) proposed an approach to cinema that pondered over the irreconcilable dualism on which, according to Foucault, all knowledge is based (the gulf between the visible and the expressible, absolute heterogeneity: to see is not to speak; to speak is not to see), he took a position somewhere between Kant (the fracturing of the cogito) and Blanchot (a poetics of the limit: to speak the silence; to see what cannot be seen) to better penetrate those examples of modern audiovisual cinema that might shed a little light on and help to conceive of that ineffable type of relationship that is the non-relationship. It was without doubt one of the French philosopher’s great digressions and conceptualisations, the description of that kind of sound film that broke with the poetics of off-screen space, where the non-seen still belonged to the visual, and established something else: a combat where “the word tells a story that is not seen [and] the visual image shows places that do not have or no longer have a story” (Deleuze, 1985: 186). It is a poetics of the emergence of the happening; one buried, covered, and drawn out from below by the word. “Beneath the earth, I shall capture the dead (Straub). Beneath the dance, I shall capture the other dance (Duras)” (Deleuze, 1985: 188). Deleuze spoke of the cinema of disjunction between the visual and the sonic –which provides an aerial word and a subterranean vision– and analysed films like Shoah (Claude Lanzmann, 1985), Fortini/Cani (Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub, 1977), India Song (Marguerite Duras, 1975) and Les photos d’Alix (Jean Estuache, 1980).

And if his digression, as I suggested above, sought, with greater or lesser success, to clarify Foucault’s epistemology, in the end, if it established anything, it was, curiously, the reversibility of the passage, since from Foucault himself came the illumination that aided a clearer reflection on that type of film that showed by silencing and revealed by blinding, when he identified the series of crosslinks between figure and text: “attacks launched by one against the other, arrows shot at the enemy target, enterprises of subversion and destruction, lance blows and wounds, a battle” (Foucault, 1973: 26). What was identified, then, was a certain kind of violence, a warlike conflict between two forces that linked filmmakers like Lanzmann, Straub/Huillet, Duras and Eustache and in which the leading role was given to a voice-over at war with the flow of images. And the sensation provoked by these examples, as Deleuze wisely noted, was that if the two sides touched, everything died.

This radical dualism –its proudly two-sided nature– was the source of stern and terrifying pedagogies (from Isou’s cinematographic lettrism to collective experiences such as those of the Dziga Vertov Group) which, turning their back on synchronies, charged against the representative function of cinema and its search for truth in the concordance between the spoken and the seen alone; ultimately, cinema was threatened, and it was a threat of dismantling, destruction and recommencement. There are many examples; this is what was suggested in La femme du Gange (Marguerite Duras, 1974), where the film of the voices and the film of the vision unfolded in parallel, opening with the ironic and agonising voice of Duras herself –the mermaid’s voice that calls cinema to its perdition (Chion, 1984: 125)- explaining absence of isomorphism as a kind of self-protection and at the same time encouraging the spectator’s contempt (the aim was to overcome cinema’s heritage and test how far it could go (Duras, 1980: 145).

It is also evident, much later, in the stunning work of the Austrian filmmaker Gerhard B. Friedl, with films like Knittelfeld – Stadt ohne Geschichte (1997) and, especially, Hat Wolff von Amerongen Konkursdelikte begangen? (2004). Where Duras rehearsed destruction, Friedl injected the seeds of disintegration, a bloodletting whereby the tracks acquired an unpredictable, accidental fluidity, at times outlining minor and deceptive agreements: the word journeying from its original silence, the image marching reluctantly on its way to black, as if seduced by the rhythmic opaqueness that speckles any projection. Playing with the wet dream of television (which is the same as it always was: the pretence of informing without explaining anything, merely by vomiting words over inconsequential pan shots), Friedl associated the social crisis of capital and of representation in a visionary diptych that ultimately declared that there was nothing to see in modern economies, and nothing to hear in the voices that claimed the power to clarify them and reveal the vast web of global connections that sustain them. Further examples could be described of this cinema of buried happenings and words flying on the air, of the visible concealed in the invisible that is drawn out by a mise en scene of word and voice that thus strips away “the silence from texts and the deceit of the bodies that pretend to embody them” (Rancière, 1996: 43). But what needs to be underlined is that this is where the great utopia of sound is encoded, marginal, secretive and severe perhaps, represented over time by a film corpus that redirected the wistfulness associated with the birth of the two tracks towards a horizon of violent optimism. It is this utopia that blinds, burns and silences what we should not forget when conceiving of an audiovisual cinema, as it overshadows any work that seeks its ethical and aesthetic position on the basis of the erotic connection between visibilities and utterances, especially when the latter are introduced by voices and sounds which, overshadowing the image and its out-of-frame, abandon a clearly defined position in relation to it.

The utopian force of disjunctive cinema is thus intimately related to the loss of innocence brought –and, of course, voiced– by the sound film, as the history of sound films is the history of a monomaniacal hunt associated with the thresholds of rupture, the unveilings and emergence of the film beneath the film. Thus, even in the earliest days of sound, as Chion (1984: 43-53) explains in his analysis of The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse, Fritz Lang, 1932), signs of the particular otherworldliness of cinema began to build up once again with the exchange of captions and dissolves for voices and words: the inference that behind the acousmetre –the neologism coined by the author by combining “acousmatique” and “être” to refer to the bodiless voices that narrate, announce and arouse the evocation of the past in films– was hidden the acousmachine (the slate disc whirling on its own); that the acousmatic, in short, was the antechamber or the sign of the automatic. And Chion, in an inspired work, explored the tensions introduced by this malevolent and unfathomable voice behind which lay protagonists who, in this process of searching, would come close to self-awareness, almost to suspect their status as shadows, simulacra and projections. The spectator, as in the early days, could more easily deconstruct the hallucinatory oxymoron of cinema, that funereal life now filled with spellbinding voices that seemed to herald a perdition: “When it is not the voice of the dead man, the voice-over of the narrator is usually that of one almost dead, one who has reached the end of his life and is merely awaiting death” (Chion, 1984: 55). The acousmatic voice and the sounds that tinged and seduced the image from an ineffable point off camera continued with the narrative task but in doing so they exposed the artificiality of the project itself, which they injected with a playful virtuality: voices without endorsement, impostors, undefined, from the hereafter or previously registered, the voices of the machine; mannerism and the decline of the genres and the modern experience would only make the fragilities and suspicions all the more acute. It is this situation that Jean Narboni appears to be referring to in a significant article on Fortini/Cani, when he attempts to define what differentiates the practice of the Straub/Huillet pairing from that of Resnais: “[...] we find in Resnais’ work (except, perhaps, for the admirable Muriel [Muriel ou Le temps d’un retour, 1963]) all of the elements which, according to Freud, structure the obsessive machine: ‘Animism, magic and witchcraft, the omnipotence of thoughts, man’s attitude to death, involuntary repetition and the castration complex…’ (in The Uncanny). Hence the dread that it exudes and arouses (taken to its most extreme level in Providence [1977]). In Straub, on the other hand, in spite of the harshness or the horror of the topics addressed, there is a kind of profound joy. The thankless work of mourning has nothing to do with passion for the corpse: the first is joyful, the second is not” (Narboni, 1997: 14). Mourning or passion for the corpse, profound joy or dread. This specific bipolarity is what breaks away from sound and from its thanatic supplement (and what underlies the utopian drift concealed in the work on the non-relationship between tracks is a certain movement against the grain), and it might well be a useful framework of concepts for evaluating the different uses of the voice-over in the contemporary fiction film, a resource as hackneyed as any other but one that has constituted a field of experimentation for filmmakers who have created works with ideas bigger than their budgets.

It might be interesting to begin with some of those filmmakers who have been exposed to the Straubian pedagogy, i.e., the work of filming between gaps and absences, on the basis of a forgetting, of an assumed loss, according to which nothing pre-exists the shots, and everything must be assembled on their basis. With films that are as conscientiously produced as they are sacrificed to random fate, the work of Straub/Huillet was and is one of the present and of impurity, where everything exists on a level playing field as long as it is translated by the machines brought together for the task. Everything counts in it, as Narboni suggests, and therefore any question as to the hierarchy of images and sounds is of no significance (a pedagogy that is also Godardian). A cinematic ally would be Jean-Claude Rousseau, who adopts these teachings to delve in his own way into a cinema of sensuality that focuses on the desire for fiction, the faith in those precise, beautiful constellations that can be formed by the constitutive components of filmmaking, which for him are the image as vision –dense lighting aided by a deliberate Lumièresque contrast– and sounds and voices as sources of resonance, which modify and magnify. The manifesto-film in this sense might be La vallée close (Jean-Claude Rousseau, 1995), that polysemic closed space where heterogeneous and even antithetical elements demonstrate the potentiality of their interactions: here the bowshots, the combats, the accidents between visual and sound tracks give rise gradually to an amorous encounter, while the geography lesson that dominated the out-of-frame and structured the film’s beginning loses its hegemony and, as Rousseau himself would corroborate (Neyrat and Rousseau, 2008), disintegrates into a heap of distractions and floating voices, visual and sonic wanderings that reveal the nature of the experiment: the film of a bad student who abandons the lesson and, like the child in Rentrée des classes (Jacques Rozier, 1956), goes off into the woods, his senses aroused. In Rousseau there is a poetics of space that places the inside in confrontation with the outside, the closed room with the open sky, the school with the street, the voice within with the calls from without. This interlinking of stimuli is a feature of Rousseau’s films like Les antiquités de Rome (1991), De son appartement (2007) and, in a register more in keeping with my exploration here, Série Noire (2009), where the filmmaker occupies the in-between space: looking through the window, between the house and the parking lot, out of our sight, and also out of sight of the person calling him on the phone, but nevertheless present, observing and possibly delirious. It is once again the right, prodigious shot, a shot that facilitates everything, in this case an omen, an augury of fiction on the fixed frame fed by the depths of voices and sound tracks. The autonomy between sound and vision, their short circuits and hints of synchrony, make the out-of-frame an out-of-film as well, and at the same time the answered prayer (the appearance of the car with all its cinematographic metaphorics) excites all the molecules that Rousseau had put into combat over the precise, neutral shot. Patience and chance, the search and the unpredictable turn the clashes into convergences, and thus the frictions between the horizontal and the vertical increase in intensity, infected by the lack of rigidity of the approach.

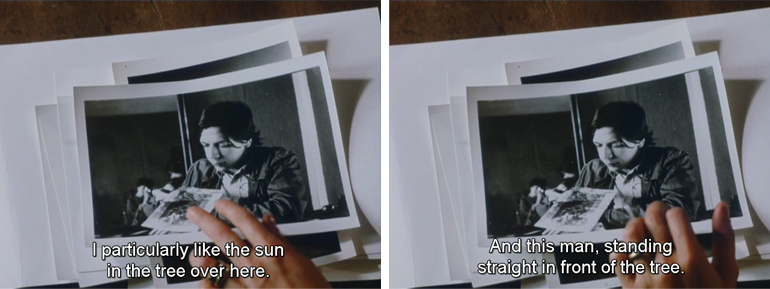

Another filmmaker following the tradition of profound joy might be Jean-Charles Fitoussi, whose Les jours où je n’existe pas (2002) seeks to balance the pleasure of the narration with that of the visuals by means of a stitch work conceived and executed to turn the ontological absolutes of film into material for fiction. And it is the opening voice –but especially the voice-over– that conveys Antoine’s story that in turn translates the delicate passages between camera shots and words into another language. While the story is told of the man who exists only every other day, the images –still frames separated by the nocturnal intermittence of the shutter– are possessed by a solemnity that infuses them with a quality of self-sufficiency. As they brush up against the words and confront each other, these images create in each change of shot an interstice that tinges the visible with mystery. Once again, then, we find indeterminacy; the gaps, the ellipses, and on them the serious game of the story that has its core in a Raúl Ruiz-styled conversation between an adult-child and a child-adult that conceives a world: cinema, like the protagonist, is overwhelmed by the dark side of time, the pure virtuality of matter without memory, the urban documentary that storms the film, taking advantage of Antoine’s absence, and speaks to us of the time before the centre of indeterminacy, before the point of view: they are the images for nobody –light for nobody– of which Deleuze would speak, following Bergson3. Against this, Fitoussi opposes the near-life of cinema (which is also the half-life of the cinephile, who always leaves the other half facing the screen) and its titanic effort to fragment and parcel up time, which escapes through the cracks between visions and voices.

It is the arduous and painstaking work of the resistance fighter –not all that far from kindred spirits like Straub or Costa, and thus close to the invocation of the classic embers– that breaks the synchrony with life and movement and scans headlands and heights: a cinema of searching for presences that can be crucibles of temporality. The oral transmission of Antoine’s story leads ultimately to an empty shot –but one that is still viewed– in a primeval virgin landscape where everything begins again. It is an art of resonance: the story here, paired with the music, is that which, as Jean-Luc Nancy writes (following Lacoue-Labarthe), had already begun and echoes still (2012: 179-180). It is the unending and unbeginning of great fiction, which besieges the music in the form of refrains, repetitions, variations and retransmissions.

A final combatant on this front might be Nicolas Rey. Subterranean relationships, faith in machines and a predisposition for twists of fate that inject ineffable additions into the fictive effort also structure his recent film anders, Molussien (2012). The outdated 16-mm reels exacerbate the ultimate ignorance as to what is being filmed (more still if, as is the case here, gadgets are constructed to steal the shots from reality, and then the order of the reels is left to the mercy of the projectionist): ordinary landscapes cut across with strangeness. The utopian scheme is repeated: Arte Povera to better penetrate the visible and get to what lies beneath, to what was always there. Of course, the question of faith is repeated: Günther Anders’ anti-fascist novel about the imaginary dictatorial Molussia, which Rey cannot read because he doesn’t know German, is where the filmmaker has placed his hope. To speak this text read by so few, to make it heard through a complicit voice, feels like something necessary and important, and it is from this fragile out-of-frame –shared with noises and other sound incidents– that picks up the conversations of the prisoners in the catacomb from where the shots will be fired, from where the combat will be established with the simple shots of urban, natural and industrial landscapes where Fascism once lurked, now transformed. Also positioned against the dictatorship of synchrony and even against conventional editing techniques is his earlier work Les Soviets plus l’électricité (2002), a stirring clash between the avant-garde and the European essayistic tradition, whose place of enunciation lies somewhere between Mekas and Marker (Blümlinger, 2006: 45). In this film-journey where, as Boris Lehman points out4, Rey becomes a voluntary prisoner on the road to Siberia, images and voice once again celebrate their immodest independence, competing, clashing swords: on one side, the voice of Rey himself, captured by a Dictaphone where he records his reflections, digressions and descriptions of what we do not see; on the other side, the images, shot at nine frames per second, enigmatic souvenirs which, not circumscribed by the word, complete and contrast their meanings as they shake the spectator with a sensory and imaginary overload. Rey re-establishes a disorder, adding new machines and reconfiguring the old ones, re-appropriating the reflection of freedom of that cinema that once sounded revolutionary and that now fights depression with beauty’s remains and dialectic essays based on the poetics and the politics of the non-relationship.

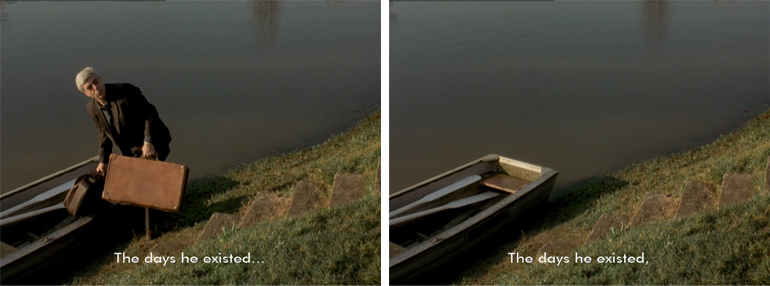

After utopia, I should speak at least minimally of the ghosts, of that type of mourning in which Narboni detected passion for the corpse. In the cinema wounded by melancholy, the rivalry between tracks has been replaced by less traumatic frictions, in essence by a system of relays. And if the interval between movements bears any obvious hallmark it is that of demiurgic post-production: images make explicit the work that domesticated them, appearing as something already seen by another (hence, perhaps, the unspeakable sadness), and the voice, which commands, as something that colours them, puts them in perspective, changes their signification and proves their malleability. There are models that induce euphoria, such as Moi, un noir (Jean Rouch, 1958), and others that are openly comic, like The Girl Chewing Gum (John Smith, 1976), or warm-hearted, like Langsammer Sommer (John Cook, 1976), but in none is it hidden that they deal with reflections, not presences. The change is from the otherworld glimpsed to the otherworld summoned; from the relationships of incommensurability between tracks in the resolution to turn the fragile and transitory nature of cinema, its status as an embalming kit of lights and shadows, into the site of a narrative reconquest whose raison d'être is the disassociation of voice and body, a source of alienation and of the fantastic, as was evident to Jean-Louis Leutrat, who offers the semantic field of this corpus (1995): the last days, prophetic and spectral time, confinement, redundancy, loop, repetition. It is the purest desire of fiction, which in reality shrouds a death rattle, which tends to structure the blueprint for a voice-cinema –embodied in an acousmetre with full powers or not– that absorbs the spectator and directs the gaze upon the visual flow. And the more severe the prison for viewing and images, the more obtuse will be their meaning by the time the voice is interrupted or silenced. A wealth of examples in this sense can be found in recent Portuguese films, painstakingly studied by Glòria Salvadó precisely under these precepts of invocation of the past and emergence of spectres5: cracked tales re-appropriated through the dialectics of editing –with those of voice/image in a privileged position– that tinge the reality with fantastic elements, with vestiges that operate from an achronological perspective and offer an imaginary intensification of memory: a few cases that could be cited briefly are Tabu (2012) and Redemption (2013) by Miguel Gomes, in which the voice revises, embellishes, creates or invents memories over images in a process of emancipation, whether for photogenic beauty or from an overdose of punctum; another is A última vez que vi Macau (João Pedro Rodrigues and João Rui Guerra da Mata, 2012), a veritable handbook for the acousmatic voice as primal force and floating residue: entranced voices that inhabit a Macao of sentimental ruins and cinematic dreams where everything seems to have already happened and all that remain are their arabesques on the air (voices that still converse in the present and govern the noir plot; voices of the protagonists, who wander close to Resnais or Mizoguchi, obsessed with fetishes, with nothing to communicate beyond the ashes and failure of past experiences). This hurried glance at Portuguese film could be closed by Rita Azevedo Gomes and her A vingança de uma mulher (2012), a film articulated from off-camera by idle, trapped actors whose voices, in relay, invite us into the sumptuous and contrived melodrama (the L’Herbier-Resnais-Ruiz axis) where the word is a weapon that seeks to tell all; a missile that bounces off mirrors, capable only of evoking and showing the torments of the past.

Once again there is the feeling that in these lives/films real life is missing, as we hear in one of her masterpieces, O som da terra a tremer (1990), the story of a hapless writer, allergic to travel, who seeks a discipline for his writing while the images seem to express a longing for escape, improvisation, an asynchronous flight that would set them free in his voice.

I will conclude with the observation that in the tomb-cinema, the experience of a growing tension between voices and visions fuels the idea of a dialogue between mourning processions, one optimistic and the other agonising. An intermediate figure for considering this exchange might be Ben Rivers and his imaginary ethnography. An heir to the tradition of Werner Herzog (Fata Morgana, 1969), Rivers’ cosmogonic impulse suspends his films between precisions and imprecisions: their inhuman hallmark is exploited, as Epstein noted, in that the machines of cinema vest sights and sounds with a material overload that goes beyond narrative intentions and subjects them to a transcendental ambiguity. Thus, in Rivers’ films like Astika (2006), Ah, Liberty (2008), Two Years at Sea (2011) and Slow Action (2011), the voices resemble psychophonies and the images resemble a historical excess or a futuristic delirium. And not even the synchrony between tracks, when it occurs, can calm or naturalise the uncertain discords.

Translated from Spanish by Martin Boyd

ENDNOTES

1 / For example in Serge Daney: Itinéraire d'un ‘ciné-fils’ (Pierre-André Boutang, Dominique Rabourdin, 1992).

2 / In conversation with Daney himself, in Jacques Rivette. Le veilleur (Claire Denis, Serge Daney, 1990).

3 / For an exploration of these concepts, see the chapters “La ceroidad y los signos de la imagen-percepción” and “Paréntesis sobre cine experimental. Kurosawa y la acción”. In: DELEUZE, Gilles (1982/83): Los signos del movimiento y el tiempo. Cine II. Cactus, Buenos Aires, 2011.

4 / An article on Rey's film published on the filmmaker's website.

5 / Especially the introduction (“Imatge i història”) and the chapters “Empremtes de la història” and “Evocació de fantasmes” in: SALVADÓ CORRETGER, Glòria: Espectres del cinema portuguès contemporani. Història i fantasma en les imatges. Lleonard Muntaner/Instituto Camões, Palma de Mallorca, 2012.

ABSTRACT

The advent of sound, in addition to identifying cinema’s first loss –the silent film– entailed the emergence of the voice, whose disjunctive and contrapuntal possibilities in relation to the flow of images would not take long to be buried in favour of a synchronous cinema and the convention of shot/reverse shot as the perfected visual translation of dialogue exchange (voices embodied by the physical presence of the stars). The split between two tracks has nevertheless been exploited by some of the most important filmmakers throughout film history, who saw in the combat between words and images a way of being faithful, in a different sense, to cinema’s main mission: to make the invisible visible through the observable. Thus, filmmakers like Straub/Huillet, Duras, Lanzmann, Eustache and Friedl chose to work on presenting the word cast into the air as a penetrating source of images of the real; images that conceal occurrences that the off-camera voices or voice-overs attract and draw to the surface. This violent and optimistic type of cinema is what Jean Narboni associated with a thankless yet joyful task in contrast with the makers of necrophiliac cinema like Resnais. This division of positions in relation to the melancholy of the sound era can be explored to analyse various cases of the use of the voice-over as a fiction stimulator in contemporary cinema. Under the influence of Straubian pedagogy, the films of Rousseau, Fitoussi or Rey could be cited. Within the spectral group, with their passion for spectres but also for the survival of memory in a fantastic style are contemporary Portuguese filmmakers like Miguel Gomes, João Pedro Rodrigues and Rita Azevedo Gomes. Half way between these two groups, reaping post-modern rewards from both ethical-aesthetic approaches, we could locate the films of Ben Rivers.

KEYWORDS

Sound films, joyful mourning, voice-over, Jean Marie Straub/Danièle Huillet, Marguerite Duras, Gerhard B. Friedl, Jean-Charles Fitoussi, Jean-Claude Rousseau, contemporary Portuguese cinema, Ben Rivers.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BALÁZS, Béla (1970). Theory of the film. Character and Growth of a New Art. New York: Dover.

BLÜMLINGER, Christa (2006). “L’électricité, moins les Soviets”. Images de la Culture nº 21.

CHION, Michel (2004). La voz en el cine. Madrid: Cátedra.

DELEUZE, Gilles (2011). Los signos del movimiento y el tiempo. Cine II. Buenos Aires: Cactus.

DELEUZE, Gilles (2013). “Heterogeneidad y relación entre visibilidades y enunciados. Kant, Blanchot y el cine”. In: El saber. Curso sobre Foucault. Tomo I. Buenos Aires: Cactus.

DURAS, Marguerite (1990). Los ojos verdes. Barcelona: Ediciones Paradigma.

FOUCAULT, Michel (1983). This Is Not A Pipe. Berkeley: University of California Press, Berkeley.

LEUTRAT, Jean-Louis (1999). Vida de fantasmas. Lo fantástico en el cine. Valencia: Ediciones de la Mirada.

NANCY, Jean-Luc (2013). “Relato, recitación, recitativo”. In: La partición de las artes. Valencia: Pre-Textos/Universidad Politécnica de Valencia.

NARBONI, Jean (1997). “Là”. Cahiers du cinéma, nº 275, april.

NEYRAT, Cyril, ROUSSEAU, Jean-Claude (2008). Lancés à travers le vide... La vallée close: entretien, genèse, essai, paroles. Nantes: Capricci.

RANCIÈRE, Jacques (2013). Figuras de la historia. Buenos Aires: Eterna Cadencia.

RANCIÈRE, Jacques (2012). Las distancias del cine. Pontevedra: Ellago Ediciones.

SALVADÓ CORRETGER, Glòria (2012). Espectres del cinema portuguès contemporani. Història i fantasma en les imatges. Palma de Mallorca: Lleonard Muntaner/Instituto Camões.

ALFONSO CRESPO

Film critic. Holds a Bachelor’s degree in Audiovisual Communication from the Universidad de Sevilla and a Master’s in History and Aesthetics of Cinematography from the Universidad de Valladolid. Author of the book Un cine febril. Herzog y El enigma de Kaspar Hauser (Metropolisiana, Sevilla, 2008), and editor of the anthology El batallón de las sombras. Nuevas formas documentales del cine español (Ediciones GPS, Madrid, 2006). Crespo writes about film, literature and theatre for the newspaper Diario de Sevilla, to which he has been a contributor since the year 2000 and where he edits the blog “News from Home”; he has also contributed to a wide range of specialist journals (Letras de Cine, Cámara Lenta, Lumière, So-Film España, Cinema Comparat/ive Cinema) and books (Claire Denis. Fusión fría).

Nº 3 WORDS AS IMAGES, THE VOICE-OVER

Editorial

Manuel Garin

DOCUMENTS

As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty

Jonas Mekas

The Word Is Image

Manoel de Oliveira

Back to Voice: on Voices over, in, out, through

Serge Daney

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Sounds with Open Eyes (or Keep Describing so that I Can See Better). Interview to Rita Azevedo Gomes

Álvaro Arroba

ARTICLES

Further Remarks on Showing and Telling

Sarah Kozloff

Ars poetica. The Filmmaker's Voice.

Gonzalo de Lucas

Voices at the Altar of Mourning: Challenges, Affliction

Alfonso Crespo

Siren Song: the Narrating Voice in Two Films by Raúl Ruiz

David Heinemann

REVIEWS

Gertrud Koch. Screen Dynamics. Mapping the Borders of Cinema

Gerard Casau

Sergi Sánchez. Hacia una imagen no-tiempo. Deleuze y el cine contemporáneo

Shaila García-Catalán

Antonio Somaini. Ejzenštejn. Il cinema, le arti, il montaggio

Alan Salvadó