ARS POETICA. THE FILMMAKER'S VOICE.

Gonzalo de Lucas

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / ENDNOTE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / ENDNOTE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

1. THE VOLUME TOO HIGH. VERTOV / GODARD / MARKER

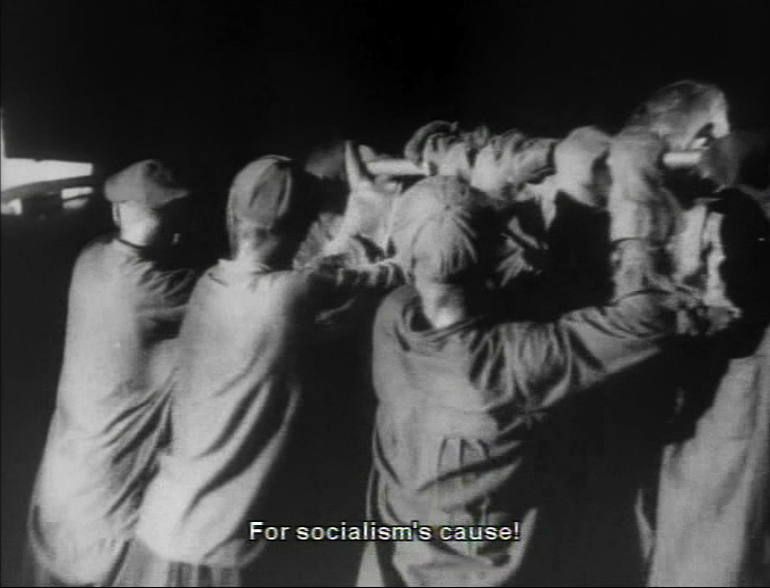

Dziga Vertov conceived Enthusiasm: Symphony of Donbass (Entuziazm: Simfoniya Donbassa, 1930) as a search for synchronising the sound of the cinematographic form and the Bolshevik revolution. The film opens with the images of a young woman who, after putting on headphones, wants to tune into a new sound: the sound of revolution and a new world. Initially this is a faint sound that can barely be captured from its distant wavelength, meaning that the film will be an approximation of this sound, of this symphony that the film has to work on and for which Vertov and his team embarked on the “assault of the sounds of Donbass […] totally deprived of the laboratory and installations, without any chance of hearing what had been recorded and to monitor our work and the work of the equipment. In conditions that meant that the exceptional nervous tension of the members of the group was accompanied by work that is not only cerebral but also muscular […] we ended up with the immobility of the sound-recording equipment and, for the first time in the world, we fixed in a documentary style the main sounds of an industrial region (sounds of mines, factories, trains)” (Vertov, 1974: 250-251).

In the first part of the film, before we are hit by the barrage of new sounds of industrialisation, Vertov creates a series of disjunctures between the images and sounds of the immobile and decadent pre-socialist society –drunkards, worshippers, a society entrenched in the old forms– together with the images and sounds of the revolution –the collective and industrialisation– which collide with this paralysed world until they make it shake and crumble (“the fight against religion is the fight towards a new life”).

This is a montage of the four forms (old sound, old image, new sound, new image), revealing different relationships and combinations between them. Eventually, the montage shows how the old way has been formally superseded by the industrialised and socialist world, with substituted symbols and forms, until the factory sirens synchronise with the new sounds, such as the singing of the International.

For years, people believed in this symphony and in its cinematographic and political truth. Nevertheless, in the mid 1970s, in the aftermath the student revolts had petered out and following the Maoist years, Godard decided to review his era with the Dziga Vertov Group by criticising himself for “turning the volume up too high”. This also indirectly involved a critical essay on the ideological relationship between image and sound in Vertov’s work. In Here and Elsewhere (Ici et ailleurs, Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville, 1975) Godard picked up the images he had shot with Jean-Pierre Gorin in Palestine (ailleurs/elsewhere) in 1970, and related them to the current situation of French society in 1975 (ici/here) in order to see what there would be between them (et/and). For the purpose of this critical research, Godard decided to use his voice –the first person– and the dialogue with his partner, Anne-Marie Miéville, to see what there would be between them, through the production of the film itself.

Following his desire to immerse himself in a collective, to relinquish the ego, which had characterised his practice with the Dziga Vertov Group during the preceding years, Godard returned to personal experience which he encapsulated by inscribing the voice and a dialogue between a couple as material for the memory –the history of cinema and his history as a filmmaker, which he encapsulated with his voice in order to review it through his companion’s answers. The domestic space or studio was to be the place to work with the tools of cinema, to free the images from their servitude to the text and discourse by modulating the voice as an instrument for interpreting an emotion or an idea.

A central motif in Here and Elsewhere, in the part looking at society in 1975, is a domestic scene showing a French family in front of a television set. Two sounds are contrasted in this space: the sound of the family, with their real problems, and the sound of the TV, which eventually silences or drowns out the voices of the family –the viewers. In one of the scenes, the woman asks her family to “turn the sound down” and then Godard’s voice says, while showing images of a man playing pin-ball and a cleaning woman turning up the radio: “Turn the volume up. How does it actually happen? Sometimes like this. And sometimes like that too. Or like this”. With an educational approach, Godard, who had spent years in hospital following a motorcycle accident, examines the basic elements of image and sound with the aim of once again starting from scratch with the cinematic alphabet. This gave him the idea of showing the VU indicator and the recording techniques: the mechanics of the process.

However, Godard not only visualises the sound, but also finds the conceptual and dramatized reflection in technique by showing the contrast –the bad relationship– between the needle registering the sound of the family and the needle showing the sound of the television which drowns out the family’s voices: “Well, let’s break up one of these movements. And let’s look slowly. We see that there isn’t a single movement, but two movements. There are two movements of sound, one moving in relation to the other. And at times of a lack of imagination and panic there is always one that seizes power. For instance here, the noise of the school and the noise of the family comes first. Next comes the noise that drowns out the noise of the family and the school. There is always a movement at a point in time when a sound seizes power from the others. A point in time when this sound almost desperately searches to hang on to this power. How has this sound been able to seize power?”. At the end of this scene, we hear fragments of a fiery speech by Hitler while the needle hits the red area in a dynamic synchronisation with the rises in pitch in his voice.

In 1991, in a conversation with the filmmaker Artavazd Pelechian, Godard pointed out that: “The technology of the talkies arrived at the same time as the rise of fascism in Europe, which was also the time when the speaker had arrived. Hitler was a great speaker, and so were Mussolini, Churchill, de Gaulle and Stalin. The talkie was the triumph of the theatrical scenario over the visual language that you have been speaking about, the language that existed before the curse of Babel” (Godard in Aidelman and De Lucas, 2010: 283).

From the mid 1970s, the idea that the use of sound and the word had been used to obliterate the visible, to stop us from seeing and to impose the text over the image, would be a recurring theme for Godard in his observations on Film History. He began these reflections in Here and Elsewhere in a self-critical sense by reviewing his own political works and the forms of political cinema: “We did what many others were doing. We made images and we turned the volume up too high. With any image: Vietnam. Always the same sound, always too loud, Prague, Montevideo, May ’68 in France, Italy, Chinese Cultural Revolution, strikes in Poland, torture in Spain, Ireland, Portugal, Chile, Palestine. The sound so loud that it ended up drowning out the voice that it wanted to get out of the image”.

This “sound so loud” involves, by extension, a criticism of the way Vertov edited sound. In Enthusiasm: Symphony of Donbass the images of the mines and factories filmed by Vertov, appear together with the sound of chants and slogans, giving rise to a stylisation that also tampered with the visible and was an error of political interpretation: the real working conditions in the factories were being concealed and by turning the volume up too high the image became a prisoner of the sound. Moreover, what was specific, together with cinema’s characteristic ability to make distinctions was lost, and from then on all left-wing movements would join together in the same sound, the same song or discourse like an opaque verbal filter that prevented the diversity of the images of the different realities from being seen.

This is why Godard broached ways of making the voice present without the word being repressive or the meaning of the image imposing itself. In order to do so, he found room for the word of the other, accepting his admonishment. Just after their reflections on revolutionary sounds, Godard and Miéville show a shot of a child filmed in Palestine in 1970. As in other parts of Here and Elsewhere, the relationship between them, the dialogue, Miéville’s voice, intervenes to critically analyse Godard’s previous work:

“Godard: Among the ruins of the city of Al Karamé a little girl from Al Fatah recites a poem by Mahmud Darwich, “I will resist”.

Miéville: Listen, first you need to talk about the set and the actor on this set. Or rather about the theatre. Where does this theatre come from? It comes from 1789, from the French Revolution and the liking of the members of the 1789 Convention for grandiose gestures and for shouting out their claims in public. This little girl is putting on theatre for the Palestinian Revolution, of course. She is innocent but maybe this way of doing theatre is less so”.

Here, the word doesn’t impose itself on the image in order to conceal it. In fact quite the reverse is true: it reveals the visual language compared with the theatre script. Later in the film, Anne-Marie Miéville makes another political criticism of Godard concerning the shot of a girl playing the part of a pro-Palestinian student, in which the filmmaker conceals where he’s standing by using a reverse shot.

“Godard: In Beirut, a pregnant woman is delighted to be able to give her child to the Revolution.

Miéville: That’s not the most interesting thing about this shot. This is. (Black screen). Godard’s voice: Can you say it again? Put… your head up a bit more. That’s it. (We see the image of the girl again). Miéville: The first thing I have to say. We always see the person being directed not the director. We never see the person in charge who is giving the orders. Godard’s voice: One last time. Stretch your… that’s it. Miéville: Something else isn’t working. You’ve chosen a young intellectual who sympathises with the Palestinian cause who isn’t pregnant but who agrees to play this role. And what’s more she’s young and beautiful, and you keep quiet about this. But this kind of secret soon leads to fascism”.

The relationship of power in the image is shown through Godard’s voice giving orders to the girl, who doesn’t reply, between the shots; the recorded sound (on a black screen) counteracts the off-screen space –understood here not as an imaginative opening but as an elision of the true relationship or the story of the shot: the one between the filmmaker behind the camera and the girl acting in front of it for him. It is as if Godard was willing to put his images on trial and the sound was the prosecuting evidence, the hidden evidence that was needed to reveal its nature. In this way, Godard’s voice emerges to explain the reality of the image: the mise en scène, the manipulation, the ideology the filmmaker brings into play, in spite of himself. Hence Godard’s need to create a feeling of otherness, of the other, of exchange through dialogue, in this film: there are no images without otherness, as Daney would say (2004: 269).

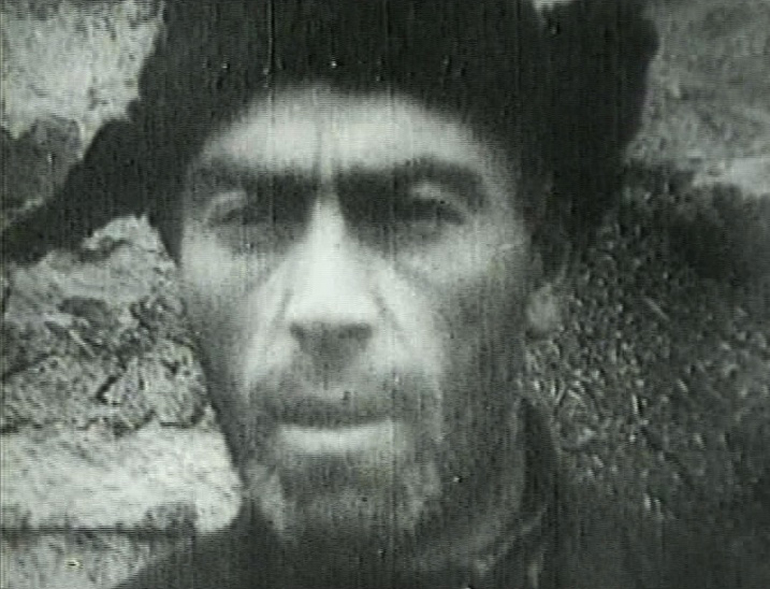

Chris Marker’s The Last Bolshevik (Le Tombeau d’Alexandre, Chris Marker, 1992) is another personal approach to and critical review of Vertov and Soviet cinema, this time formulated in a more introspective, elegiac way. After making countless political films in socialist countries –in the Soviet Union, China and Cuba– and, shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Marker establishes a dialogue with a recently deceased former comrade, the filmmaker Aleksandr Medvedkin. The film, like Godard and Miéville’s, is as much a permanent review as it is a rediscovery of the forms of Soviet cinema. Following the wonderful experience of Medvedkin’s film train, a laboratory of new forms and an educational project for learning the alphabet of cinema rolled into one (as with Vertov and Godard himself), Marker eventually finds some of the films that were thought lost: «In the end, Kolia discovered nine films from the train. I only hope the viewer’s heart will skip a beat in the same way as mine did in the editing suite when I saw the shots you had spoken to us about so much. Nobody had seen them since 1932. What I saw wasn’t an archivist’s excitement, nobody had shown them. In the 1930s, reality was made up, fabricated, staged, made edifying. Even Vertov no longer believed in life as it was. And you filmed the discussions between workers armed with your fine socialist conscience but without ever tampering with the image. According to your diary, the result was overwhelming: absenteeism, bureaucratic disorder, thefts from one workshop and another. It would have been a tall order to ask the reality of the time to be the paradigm of workers’ democracy you were hoping for. At least, the accused replied. It wasn’t time for confessions yet. And during that time of triumphalist slogans the final intertitle sounded melancholic: "Locomotive mechanics, where is your commitment?"

This film is a paradigmatic example of the history of cinema made from cinema, of the image as a trace or document of what couldn’t be seen and would be lost in the pages of books. In the end, it is the raw materials –in this case the entombed films, blinded by official history– that show, and even highlight what is real beneath the texts about the history of cinema, the slogans, the discourses and stylised propaganda images; beneath the beautiful images of the revolutionary progress of the time there was one crude and harsh reality of unmotivated workers on the Stalinist kolkhozes; with Vertov, this was indelible.

2. THE PRINCIPLE OF NOT KNOWING.

In their respective essays, Godard and Marker make a materialist criticism of cinema in which the past (the preceding images of film history and their own films) makes its presence felt through the voice, the filmmaker’s word as a means of reviewing –and exploring in greater depth through editing– critical analysis and ars poetica. Here the word is understood as a cinematographic subject –no matter how much the cliché persists about the fact that it is less cinematographic than the image– an appropriate tool for an essay or reflection in the first person about practice itself and creative doubts –in order to share the process– and at the same time a poeticised way of looking back on the experience, in the sense highlighted by José Ángel Valente: “What the scientist tries to fix in the experience is precisely what is repeatable and fleeting about it [...] experience can be known by its particular uniqueness. The poet isn’t interested in what the experience can reveal as a constant that is subject to laws, but rather in its unique, ungovernable character; namely, what is unrepeatable and fleeting about it. [...] Because the experience as a given element, as raw data, isn’t known immediately. Or, put another way, something always remains concealed or hidden in immediate experience. Man, who is subject to the complex synthesis of experience, remains enveloped by it. Experience is tumultuous, very rich, and at its height, greater that the person at its core. To a great extent, to a very great extent, it goes beyond his or her awareness. It’s a well known fact that the great (happy or terrible) events in life occur, it is often said, ‘almost without us realising’. Poetry operates precisely on this vast field of experienced yet unknown reality. This is why all poetry is, above all, a major realisation” (Valente, 1995: 67-68).

This temporary approximation of one’s own experience takes on a personal sense for filmmakers in the editing suite, when they are confronted with the things they didn’t notice when they were filming, the things that escape and overwhelm them; and not in order to fill in this knowledge, or make it complete, but to explore this area of uncertainty in greater depth. At the beginning of As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty (Jonas Mekas, 2000), Mekas’ voice makes us share in the creative principle behind his film: “I have never been able, really, to figure out where my life begins and where it ends. I have never, never been able to figure it all out, what it’s all about, what it all means. So when I began now to put all these rolls of film together, to string them together, the first idea was to keep them chronological. But then I gave up and I just began splicing them together by chance the way that I found them on the shelf. Because I really don’t know where any piece of my life really belongs, so let it be. Let it go. Just by pure chance, disorder. There is some current, some kind of order in it, order of its own, which I do not really understand same as I never understood life around me: the real life, as they say. Or the real people. I never understood them. I still do not understand them. And I do not really want to understand them”.

The voice thus draws nearer to one of the mysteries of the image, this unsaid knowledge that Godard alluded to in his criticism of the text –the photo caption, the caption, the voice over– subjugating the image. Here we should make the distinction between the image and the cliché, between the real and the poeticised image, the one that remains to be seen or made, and the cliché, the previously seen or prefabricated image. In another part of the film, Mekas says: “without knowing it, unconsciously, we all carry inside us, in some deep place, some images of paradise”. And he adds: “I have to film the snow. How much snow is there in New York? But you’ll see a lot of snow in my movies. Snow is like the mud in Lourdes. Why, whenever they paint paradise, is it always full of exotic trees and nothing else? No, my paradise is full of snow!”. Mekas’ statement involves a search for this internal image which it is so hard to see. If someone asks us about paradise, the most usual thing would be to see it through a pre-made, canonised image, the exotic landscape, the cliché. Can we find a characteristic interior image of paradise, like the one in the snow? This is certainly an image that is initially unconscious, unknown, unexpected and longed-for; these are the creative principles of the essayistic voice, embedded in doubt and searching.

This conception of the poetic experience concerns the image and the word. In a scene from Sunless (Sans soleil, 1982), Marker makes a cinematic interpretation of or creates a correspondence with Basho’s haiku: “The willow sees the heron’s image upside down”. Basho’s poem contains an image the reader has to visualise or compose in their head in order to give it its fullest meaning. However, cinema, for its part, can depict this poetic or interior and unmade image: Marker shows the image of a willow followed by another of the reflection of the tree in the water: in other words, the willow sees the heron upside down because it is viewing its own reflection (upside down) in the water. In the poem, the word means taking ourselves to the willow’s viewpoint, to its eyes, so to speak, while, in Marker’s film, we move to or are placed behind the eyes of the poet who is looking at this landscape.

The filmmaker’s voice (in the films of Cocteau, Godard, Mekas, Van der Keuken, Pasolini, Welles, Rouch, Robert Frank, Farocki, Perlov, etc.) is thus linked to the search for the poetic image –the as-yet-unseen, unthought-of image– to the gesture of creation and the uncertainty of the process, to the essay that is close to a sketch, rough draught or retrospective meditation and writings in the first person, like a letter or a diary. By associating and comparing these films or essayistic fragments, we find an inner story of cinema, which fluctuates between an aesthetic treatise and a critical interpretation. As a whole, and in their variety, they show us how filmmakers address the issues of their medium from their own practice: how to film a face; what we find out about ourselves in an image; how to shift from one shot to another; and how to develop a film project.

These uses of the voice are an integral part of essay-films and feature occasionally in fiction and documentary films, as interruptions that specify the nature of the process and the creative first person. They are often like a rough draft; they are notes and creative searches for an as-yet-unmade film, not worked out on paper or with a script but from the experience of cinema –the encounter with the places, the review of the images– just like in Pasolini’s appunti or some of Godard’s scénarios. These are sometimes interventions in a narrative film that have been generated from the cinematographic desire to the imagined film, like Glauber Rocha in The Age of the Earth (A Idade da Terra, 1980) –“The day Pasolini, the great Italian poet was murdered, I thought about filming the life of Christ in the Third World”– or even Abderrahmane Sissako in Life on Earth (La vie sur terre, 1998) –“I’ll try to film this desire, to be with you, to be in Sokolo. Far from my life here and its crazy pressing needs”.

The filmmaker’s voice is often confessional and shows and shares the dynamics of the process, the other story that films are wont to hide: the story of the film being made and thought out, as is usually the case with Jean Rouch and his participative sense of cinema. At the start of The Human Pyramid (La pyramide humaine, 1959) he says “The film we have made, instead of reflecting reality, creates another reality. The story never happened; it was constructed during filming, the actors invented their own reactions and dialogues. Spontaneous improvisation is the only rule of the game”.

The main common element is the opening up to what has been overlooked, to what the material cinema produces (in view of its technical properties) beyond our control. As with Godard, who laid himself open to questioning his ideology and practice when he reviewed the shots he had filmed in Palestine, these fragments show us hesitations or searches for possible films, doubt as the driving force behind creative thought that is aware of creative gestures. At the beginning of La villa Santo-Sospir (1953) Cocteau states that “One day, we will regret so much accuracy and artists will try to create chance accidents deliberately. Kodachrome film changes colours of its own accord, in the most unexpected way. To a certain extent, it creates. We have to accept this as if it were a painter’s interpretation and accept the surprises. It doesn’t show what I want, but what the camera and the chemical baths want. It’s another world where it’s essential to forget the one we live in”.

There is therefore a primordial recognition of not knowing in the essayistic voice: essays in order to see something that isn’t seen, something that only the camera can show. To quote Rivette: “the film knows more than I do. When I see it again, there are certain things that I never see in the same way and others that I think I discover or lose from sight, that disappear: a film is always wiser than its ‘maker’. This is what is exciting during the edit: to forget what we know and discover what we don’t know” (Cohn, 1969: 34).

Cinema explores in greater depth the fact that we can’t see things properly, or see them, from our shared experience, in a fragmented way, askew and focused by our own subjective projections –desires, fears– according to the restrictions of only seeing the exterior or the appearance of the person filmed, in order to guess at the interior or the thought. As the lover in A Married Woman (Une femme mariée, Jean-Luc Godard, 1964) says: “We kiss somebody, we caress them, but in the end we remain on the outside, like a house we never enter”. Cinema generates an act of perceptive knowledge when, through the camera, it captures a process of change, the shift of one image to another on a face, the revelation of something hitherto unseen. If there is no otherness or distinction from the other in the cliché –for instance, in the way the media make the Palestinians into the “Arab”, without the viewer being able to distinguish or specify their individual characteristics– in the image there is a real exchange between what is looking and what is being looked at. A bond or type of intimacy is thus established that acts as a linking thread or undercurrent.

In a particularly emotive scene from Diary (1973-83), David Perlov has to react to the sentimental confession and tears of his daughter, in an intimate setting that will show, through the camera, something the father didn’t know about her: “Yael has also returned from Europe. She has returned from what she calls an adventure. I can see her eyes flash. Anxiety, as if she were expecting a phone call. Something’s on her mind. I pick up words here and there, and I ask: ‘Would you say it to the camera?’ She replies: ‘Seeing as it’s you, I don’t mind’. Yael has become a young woman, and at this moment, as a father and filmmaker, I feel I am growing with her in this diary”. Later on, his voice is intercut with his daughter’s: “I could listen to her for hours, but it’s as if she weren’t talking to me or anybody else, as if she were engaged in a dialogue with life itself, with existence. There’s not much else I can do, apart from leave my camera running. My family is turning into my diary […] For the first time, I reveal something profound in my family that I was unaware of. Nevertheless, the simpler it is, the purer it is. […] I attempt a few words, but I feel they lack meaning”.

The filmmaker’s voice observes a transformation –“Yael has become a young woman”– which also affects the person behind the camera –“as a father and filmmaker, I feel I am growing with her in this diary”–, and takes on board the fallibility of his knowledge while he feels the urge to hold the shot, to reveal something in it or to move onto the next. Robert Frank says at the start of Conversations in Vermont (1969): “This film may be about learning to grow. About the past and present. It’s a kind of family album. I don’t know… it’s about…”. In these cases, the image is compared to an ellipsis and interruption. In The Lion Hunters (La chasse au Lion à l’arc, 1958-65), Jean Rouch stops his camera when a herder is bitten in the leg by a wounded lion he has rashly approached: “And suddenly a catastrophe happens. The lion, in its trap, attacks a Peul herder. I stop filming but the tape recorder keeps recording…”. The image on the screen is interrupted –we see a few stills resembling ochre traces of earth– but not the images conjured up in our minds by the sound –the victim’s cries, the roar of the lions, the noise of the hunters– this “keeping recording” that may describe the secret of chance and cinematographic shot: the material of cinema always captures something more; it always continues or extends beyond the time the filmmaker stops, even to question his actions –in this case the morality that led Rouch to stop filming the most dramatic sequence in his film.

The soundtrack, compared to the image track, is like a gesture with the left hand that we can’t control while we are thinking about the right, that part of the body that doesn’t adhere to what we thought we were showing. And the voice and the sounds don’t appear afterwards in Rouch’s editing in order to add what is missing in the scene or to fill the visual void; they do so precisely to document those other kinds of interior images, that have nothing to do with the epic and the characteristic narrative adventure of the hunters: the images of the interruption, the paralysing doubt, the fallible and incomplete gesture that being in front of a real event with a camera entails. It is as though, here, instead of the action, we saw subjectivity cross-cut by doubt at full tilt, the nervous thought that blocks and stops the body, with the reverse or the outburst of morality that paralyses and prevents us from taking a step forward, and the sound was the recording that returns from –and isn’t erased from– that life we let pass us by and cannot grasp. The one that embeds itself in our body and we can’t get rid of: and what if…?

However, if in life we have to “act” in a play that is always live, without rehearsals or the possibility of stopping the “scenes” if we make a mistake, through editing we can pause, slow down, see and see over again, and even discover blunders and foibles in the images of our lives. The essayistic voice thus contrasts two temporalities of cinema: the present of the filmed image and the present of the editing. Knowledge is generated through the coexistence of these two times, with the possibility of analysis by editing what went unnoticed, criticism through revision: the filmmaker can emerge from himself, objectivise himself by looking at what the material reveals to him about his own ideology or psychology inscribed unconsciously onto the film, or by examining the process itself. Unlike written analysis, this essayistic conception of the relationship between word and image moves in the same direction as cinema itself; from the physical matter to the idea, in contrast to figurative arts characterised by the reverse journey. Hence their approach to the aesthetic treatise, ars poetica, in which the filmmakers themselves are the narrators.

This is why the editing suite, on the same level as the typewriter, either appears on screen –as with Godard, Welles, Mekas and Farocki– or doesn’t. It occupies the place of the writing desk, of at times melancholic meditation, or of the doubtful and intuitive work of cutting, the transition between one shot and another, or stopping in the interval. Towards the end of Herman Slobbe/Blind Child 2 (Herman Slobbe/Blind kind 2 1966), Johan Van der Keuken stops the film he is making about the blind child –the interior of the film as an organism, a collapsed body– in fact, he shows us the celluloid film getting jammed inside the camera –to refer to his own work juxtaposed with historic facts, the story with History: “On 29th June, the Americans bombed Hanoi. Now we’re leaving Herman. I’m going to Spain to shoot a new film”.

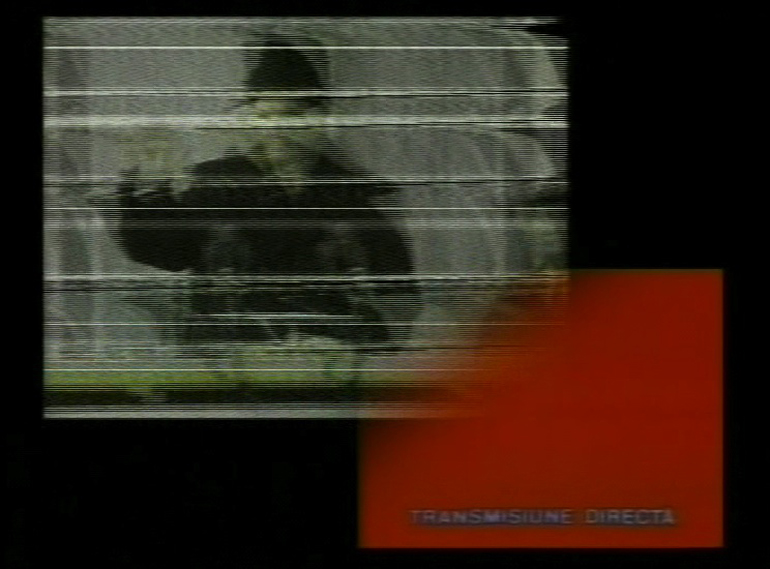

In Videograms of a Revolution (Videogramme einer Revolution, Harun Farocki, Andrei Ujica, 1992), the televised broadcast of a speech by Ceausescu is interrupted by a red screen, a break in transmission that takes place exactly at the same time as the beginning of the revolution that was to overthrow the dictatorship. Farocki asks “Was this disturbance, this interruption the sign of a revolt?” as he returns to the images in Interface (Schnisttelle, 1995). Vertov resolved this political shift –the change from one ideology to another, from one form to another– from aesthetic culmination or transcendence, but here the essay stops at the interstices in order to analyse it: this empty space of images of power, where a political system teeters on the brink because of a revolution, that still uncertain moment when we don’t know which system will win or what is going to happen.

At the end of Sans soleil, Chris Marker returns to the shots of children in a field in Iceland he had shown at the start of the film (“He said that for him it was the image of happiness and also that he had tried several times to link it to other images, but it never worked”). This time, however, he had edited them in a different way: "And that’s where my three children of Iceland came and grafted themselves in. I picked up the whole shot again, adding the somewhat hazy end, the frame trembling under the force of the wind beating us down on the cliff: everything I had cut in order to tidy up, and that said better than all the rest what I saw in that moment, why I held it at arm’s length, at zoom’s length, until its last twenty-fourth of a second”.

With this confession, Marker seems to point out that the expression of happiness he felt when he saw those children –the problem of the filmmaker with which he opens the film: precisely how to express this happiness, how to convey it– couldn’t be restored through editing, conceived conceptually or intellectually, but by cutting the very material of the scene; cinema thought about from the hand, by setting out the experience of the process and the gesture, showing what was thought surplus to requirements or an extension, the added uncertainty that makes the shoot longer, the thing that tends to be refined or cleaned up afterwards. And what do these images show that good technique would discard? While Marker initially cut the images to make the edit “sharper”, now he sees in this supposed defect –haziness, the trembling frame– a supplement to experience, the body, the presence; here we see that the wind is shared by the children and the filmmaker with his camera, and that it is the film itself that trembles in an attempt to prolong this moment of happiness and not lose it from sight.

In the fevered search for vitality, for the energy of something real that is happening in front of the camera, Pasolini also questioned the correct and finished form that had been decided beforehand, showing that the filmmaker had to review the position he was filming from, without remaining in a safe or unchangeable position. This questioning became the subject and overriding concern of his filmed appunti or notes: A Visit to Palestine (Sopralluoghi in Palestina, 1964); Notes for a Film about India (Appunti per un film sull’India, 1968); Notes for an African Orestes (Appunti per un’Orestiade Africana, 1970). On many occasions, these films involve a decision to reject. In A visit to Palestine Pasolini says “There’s not much to be said about these images. They speak for themselves. It was an adventure, a break in the journey rather than an investigation. Because, as you can see, all this material is unusable. These are the same faces we saw in the Druze villages: sweet, pretty, cheerful, perhaps a little gloomy, funereal, with a wild sweetness, completely pre-Christian. The words of Christ didn’t pass this way, far from it. The images are fantastic. And they may be faithful to the image we have when we think of the Jews crossing the desert”. In spite of the aesthetic beauty of the images, Pasolini rejects them in favour of the realism he wanted to use in the Gospel according to St. Matthew, which he couldn’t find in Palestine.

These meditative, lyrical films were produced at the same time as Pasolini’s somewhat dry articles about the semiotics of cinema in the 1960s. They are, nevertheless, the positive expression of this language, its sensitive outpouring: fleeting notes on trips and impressions of life made with the purpose of filming in order to see, to better imagine stories and to discover new faces and locations. This is why, despite the fact that they are approached as notes or notebooks, they are opposed to any abstract or conceptual theory about cinema and become the practice of cinema from the material itself, from the palpable, the sensitive, without jargon or technical terminology, but just through signs and specific details about the experience.

While Pasolini’s contact with Friulian farmworkers had led him to relinquish his early aesthetic, hermetic and intellectual poetry when he found or rediscovered his love for reality, cinema led him to “embrace life to the full. To appropriate it, to live it by recreating it. Cinema enabled me to keep in contact with reality, a physical, carnal, I would venture to say even sensual contact”.

After making a number of rather dry, politicised films, Johan Van der Keuken felt like making a summer film about family ties. The film ended up being a reflection on photography, the past and the cinematographic purpose of giving life to the immobile, of being present. Johan van der Keuken says in Filmmaker’s Holidays (Vakantie van de filmer, 1974) “The French critic André Bazin once stated that film is the only medium that can show the passage from life to death. I filmed that passage several times, but nothing could be learned from it: nothing happened. It is more difficult to show the passage from death to life, because you have to make that passage, otherwise nothing happens”. In this scene Van der Keuken shows a sequence of shots of an animal having its throat cut –this passage from life to death in which nothing happens– to later quantify the mystery and origin of cinema, of the advent of life and its creation through cinema, in the images of his children bathing in the river.

The filmmaker’s practice seems to contradict the canonical written theory, or raise the possibility of another search: of cinema as a supplement to vision and time, to life and energy, that must generate movement and duration in the fixed (photography) and wind in the shadow. A change of state as well as the change of an idea through the passage from the written, disembodied or abstracted theory of its object –in this case Bazin’s theory– to another experimental theory which, from the creative gesture, bases itself on the visible reality and the encounter with reality –“I filmed the passage from life to death several times, but nothing could be learned from it”– in order to think and say cinema in another way.

Translated from Spanish by Mark Waudby

ENDNOTE

1 / In this way, the theatrical setting in Al Karamé is connected with the TV screen that drowned out the noise of the family. In an interview about Number Two (Numéro deux, 1975), Godard said: “If the image makes you think about you and your boyfriend, I think it’s a good piece of work. […] It’s a film to think about the home rather in terms of a factory and that’s all. It’s so that the people can talk, something I’m not sure about, and talk to each other a little. Whether they fight or not, the purpose will have been achieved, if there is a purpose, when people begin discussing their problems, something specific about them, be it work, salary, etc. because the film has helped them”. (Godard in Aidelman and De Lucas, 2010: 170). Godard is already criticising cinema’s disconnection from the real problems of the viewer at the time, or the weakening of its capacity to have an effect on the viewer’s life and even make them reconsider it. In this regard, the dialogue with Anne-Marie Miéville is an exemplary exercise in this type of questioning, with the conviction that ideology must go through personal experience, which becomes political in the end.

ABSTRACT

The first part of the article compares the political cinema of Vertov, Godard and Marker, through a critique of the ideological power that sound and the word have had on the image. It goes on to suggest a series of associations between films in which the filmmaker’s voice (Mekas, Cocteau, Van der Keuken, Rouch, etc) is linked to the act of creating, the uncertainty of the process, the essay that is akin to the sketch or retrospective meditations and writings in the first person. Through the essayistic voice it develops the possibility of analysing what was invisible or went unnoticed through editing, criticism through revision: the filmmaker can emerge from himself, objectivise himself by looking at what the material reveals to him about his own ideology or psychology inscribed unconsciously onto the film, or by examining the process itself. Unlike written analysis, this essayistic conception of the relationship between word and image shares the movement from the material of cinema to the very idea behind it.

KEYWORDS

Filmmaker’s voice, Essay-film, Editing, Image / cliché, Sound and word, Political cinema, Interruption, Creative process, Principle of not knowing.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aidelman, Núria and De Lucas, Gonzalo (2010). Jean-Luc Godard. Pensar entre imágenes. Conversaciones, entrevistas, presentaciones y otros fragmentos. Barcelona: Intermedio.

Aumont, Jacques (2002). Las teorías de los cineastas. Barcelona: Paidós.

Cohn, Bernard (1969). Entretien sur L’Amour fou, avec Jacques Rivette. Positif, nº 104, April.

Comolli, Jean-Louis (2007). Ver y poder. Buenos Aires: Nueva Librería.

Daney, Serge (2004). Cine, arte del presente. Buenos Aires: Santiago Arcos.

Eisenstein , Sergei M (1986). La forma del cine. Mexico City: Siglo XXI.

Farocki, Harun (2005). Crítica de la mirada. Buenos Aires: Festival de Cine Independiente BAFICI.

Frampton , Hollis (2009). On the Camera Arts and Consecutive Matters. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Keuken , Johan van der (1998). Aventures d’un regard. Films-Photos-Textes. Paris: Cahiers du cinéma.

Mekas , Jonas (1972). Movie journal: the rise of the new American Cinema 1959-1971. New York: Macmillan.

Panofsky, Erwin (1995). Three essays on style. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Pasolini, Pier Paolo and Rohmer, Eric (1970). Pier Paolo Pasolini contra Eric Rohmer. Cine de poesía contra cine de prosa. Barcelona: Anagrama.

Vertov , Dziga (1974). Memorias de un cineasta bolchevique. Barcelona: Labor.

WATKINS, Peter (2004). Historia de una resistencia. Gijón: Festival Internacional.

VALENTE, José Ángel (1995). Las palabras de la tribu. Barcelona: Tusquets.

GONZALO DE LUCAS

Lecturer in Audiovisual Communication at Pompeu Fabra University. Film programmer for Xcèntric, Centre of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona. Director of the post-graduate programme Audiovisual Editing at IDEC/Pompeu Fabra University. He has written the books Vida secreta de las sombras (Ed. Paidós) and El blanco de los orígenes (Festival de Cine de Gijón) and co-edited Jean-Luc Godard. Pensar entre imágenes with Núria Aidelman (ed. Intermedio, 2010). He has written articles for 20 anthologies and publications such as Cahiers du Cinéma-España, Sight and Sound and the supplement Cultura/s in La Vanguardia.

Nº 3 WORDS AS IMAGES, THE VOICE-OVER

Editorial

Manuel Garin

DOCUMENTS

As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty

Jonas Mekas

The Word Is Image

Manoel de Oliveira

Back to Voice: on Voices over, in, out, through

Serge Daney

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Sounds with Open Eyes (or Keep Describing so that I Can See Better). Interview to Rita Azevedo Gomes

Álvaro Arroba

ARTICLES

Further Remarks on Showing and Telling

Sarah Kozloff

Ars poetica. The Filmmaker's Voice.

Gonzalo de Lucas

Voices at the Altar of Mourning: Challenges, Affliction

Alfonso Crespo

Siren Song: the Narrating Voice in Two Films by Raúl Ruiz

David Heinemann

REVIEWS

Gertrud Koch. Screen Dynamics. Mapping the Borders of Cinema

Gerard Casau

Sergi Sánchez. Hacia una imagen no-tiempo. Deleuze y el cine contemporáneo

Shaila García-Catalán

Antonio Somaini. Ejzenštejn. Il cinema, le arti, il montaggio

Alan Salvadó