SIREN SONG: THE NARRATING VOICE IN TWO FILMS BY RAÚL RUIZ

David Heinemann

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / ENDNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / ENDNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

In cinema, oral narration informs. It also seduces. The timbre of the voice and the often confessional nature of this intimate form of address together possess "the irrational power” –to quote André Bazin, who here describes photography– “to bear away our faith” (1967: 14). Similar to the photographic image, oral narration, and voice-over in particular, appears to have a privileged connection to filmic and, especially in the case of the documentary, profilmic reality. However, as numerous films demonstrate, from Land Without Bread (Las Hurdes, tierra sin pan, Luís Buñuel, 1933) through a body of films noirs to Badlands (Terrence Malick, 1973) and beyond, we embrace it at our interpretative peril. Though the voice may express the views of an authority (relaying personal experience or expert knowledge), it represents a point of view that is likely to be as limited, skewed or misleading as any conveyed through dialogue or image. The unreliable narrator, whether ill-informed, deluded, capricious or malicious, was a staple in the novel long before the coming of the sound film. But when employed in film, where the voice is not mediated by the written word but linked in a variety of ways to the indexical image, its power to convince is multiplied. As a cinematic device the narrating voice is thus well-suited to films which, in the pursuit of metaphysical or epistemological investigations, question received ideas about the nature of reality and human identity, and interrogate how we come to know ourselves and the world. Here the guiding voice can function as a siren song1, luring viewers into uncharted philosophical waters and shipwrecking habitual views of time, causality, identity, and cinematic form.

The prolific Chilean-born director, Raúl Ruiz, who made the majority of his over 100 films in France, endeavours in his work to challenge assumptions about reality –filmic and profilmic– through destabilising our customary relationship to the cinematic voice and image, and their relationship to each other. With a baroque and at times surrealist sensibility, comparable in literature to that of the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, Ruiz aims to proliferate meanings rather than delimit them, to disperse character and place rather than particularise them –in short, according to Ruiz himself, to foster “a space of uncertainty and polysemia” (2005: 121). Adapting Walter Benjamin’s concept of the optical unconscious2 Ruiz demonstrates, in his films and theoretical writings, how visual signs draw on, and generate other signs3. Exploited by a director who wishes to open up interpretative spaces, this excessive multiplication of signs leads to “a non-totalisable infinity of irreconcilable points of view” (Goddard, 2013: 6). Ruiz describes this passage into the photographic unconscious as an entry into a hypnotic or dream state:

“Now it appears that the images are taking off from the airport of ourselves, and flying toward the film we are seeing. Suddenly we are all the characters of the film, all the objects, all the scenery. And we experience these invisible connections with just as much intensity as the visible segment” (Ruiz, 2005: 119)

But the voice, too, is a representation, in its timbre and intonation as much as in the verbal message it conveys, and like images can be used to lull viewers into a hypnotic state and initiate them into a labyrinthine world of possible realities. Ruiz uses voice-over narration as well as on-screen narration –or ‘textual speech’ as Michel Chion designates it– to do just this.

Two of Ruiz’s most radical experiments with the power of cinema to alter the viewer’s conception of reality depend upon oral narration; indeed, each of them in their own way deconstructs the very notion of this cinematic device: The Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting (L’Hypothèse du tableau volé, 1979), and the 30-minute Ice Stories (Histoires de glace, 1987). While the former began as a documentary about the French writer and artist Pierre Klossowski, the latter marked Ruiz’s contribution to the three-part omnibus Icebreaker (Brise-glace, 1987), commissioned by the French Ministry of Foreign Affaires and the Swedish Film Institute with the ostensible objective of documenting the activities of the Swedish ship. The other two contributions were directed by Titte Törnroth and Jean Rouch. Although both Hypothesis and Ice Stories have their genesis in documentary and make liberal use of documentary devices, such as testimony, expository narration, and unstaged cinematography, both ultimately subvert the form to the degree that they must finally be classed as fiction. In employing a documentary inspired approach, however, Ruiz exploits the generally held conviction that documentary adheres closer to reality than fiction film, with the privileged relationship to truth that that brings, and thereby makes a more forceful challenge to our everyday perception of and relationship to the world. This strategy of mixing the real with the fictional was also employed by Borges in his short stories. To convince the reader of the seriousness, if not the veracity, of the narrator’s improbable claims, he employs non-fiction devices, such as bibliographic references and footnotes (‘Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote’ provides a good example), as well as references within the fictional story to historical figures who appear to endorse the fantastic events recounted, as in ‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius’ where Bertrand Russell, Schopenhauer, Hume and Berkeley are cited. Indeed, Borges went so far as to refer in his non-fiction writings to books that did not exist but were his own fabrications, a strategy employed by Klossowski and, in turn, Ruiz.

In The Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting an art collector discusses his collection of six paintings by the 19th century artist Frédéric Tonnerre, and attempts to demonstrate that the paintings are linked by their narratives, formal devices and symbols, and constitute a series that reveals a secret meaning, a meaning that created such a scandal in 19th century Parisian society that the paintings were suppressed by the government of the time. The Collector employs tableaux vivants in order to penetrate into the three dimensional spaces represented by the paintings and better explore key features, such as composition, décor and props, lighting and poses. The ultimate significance of the paintings cannot finally be pinned down, however. The Collector attributes this to a missing painting which renders the series, and the meaning it was created to articulate, incomplete. He can only hypothesise as to what this alleged painting represented, and he does so based on the interpretation he attempts to make of the series as a whole. In other words, he uses a virtual painting of his own invention to supply the necessary ‘evidence’ required to support his theory.

The film opens with a sixty-one second stationary shot of a misty cul-de-sac in contemporary Paris, presumably the street in which the Collector’s house is located. After two epigraphs over black4, the subsequent shot features the interior of the Collector’s premises where the mobile camera explores the room housing the paintings. In a dry, clean, closely-miked recording –clearly voice-over– an authoritative Narrator introduces the subject of this alleged documentary, his dramatising delivery accentuated by a surge in the strings of the classical score accompanying the scene. As the camera dollies in to an easel on which is propped a painting featuring a young man, hands tied behind him and a noose around his neck, encircled by men in religious ceremonial attire, the Narrator concludes his opening remarks:

“It is enough for the painter to interpret, in his sober, magisterial style, the dynamism of these figures, the expression of their poses and gestures, to reveal the ardent fanaticism of these men and their inexorable purpose”

A second acousmatic voice adds “J. Alboise in L’Artiste, 1889”, thus indicating that the Narrator’s florid speech is in fact a quotation, while subtly undermining the Narrator’s integrity. The reverberant quality of this second voice suggests it emanates from a space different from that of the Narrator, possibly the space represented on screen. This proves to be the case when, a moment later, just as the Narrator finishes another statement about the painter, the Collector (played by Jean Rougeul) steps out from behind the painting under discussion and walks thoughtfully across the room, once more vocally providing the reference to the Narrator’s speech: “M.F. Lajenevals, Revue des Deux Mondes, 1889”. The Borgesian strategy of validating unlikely claims through fictive academic references seems here designed as much for the sake of parody as for persuasion. Inhabiting different spaces, the two characters also inhabit different times: the Narrator a time subsequent to that in which the images of the film were recorded, and the Collector precisely the time in which he was photographed by the camera. The two men nevertheless communicate across this spatio-temporal divide, at times concurring, at others disagreeing. When the Narrator begins to formulate a question about the series of paintings (“How is it that only six paintings”), the Collector cuts him off: “Seven”. This establishes the difference between the two men’s approach to the paintings, as well as the problematic at the centre of the film: the nature and limit of exegetical activity.

The Narrator manages the proceedings –not as an off-screen narrator normally does in a documentary, but ‘live’– similar to the commentator of a televised sporting event. He describes the Collector’s activities as he moves from room to room and asks leading, portentous questions of the Collector, then clarifies or summarises his answers. This creates the expectation of a definitive solution to the double-barrelled mystery stated at the outset: what is the secret at the heart of the series of paintings and why did it create a scandal in 19th century Paris. He attempts in this way to give shape and meaning to the film (within a film), even if this entails foreclosing the Collector’s elaborate speculations. Having witnessed just the first two of the tableau vivant stagings of the six paintings, the Narrator is already prepared to offer a summary interpretation:

“Narrator: Perhaps one might now venture the hypothesis of a group of paintings whose interconnection is ensured by a play of mirrors.

Collector: Speculation.

Narrator: One might see the painter’s oeuvre as a vast reflection on the art of reproduction.

Collector: Certainly not. That is not the way to look at this painting”

Whereas the Narrator drives toward interpretative closure, the Collector continues to open new lines of investigation, creating a labyrinth of possible meanings. The interplay between the Narrator and the Collector provides the basis of this parody of expository television arts documentaries –programmes that attempt neatly to sum up complex and multivalent works of art– and also highlights key preoccupations of both Ruiz and the ostensible subject of this project, Pierre Klossowski: how the refashioning of works of art creates a subjective, circular time, and how this act, and the temporal disjunction it creates, begin to dissolve human identity. Both concepts find expression in the tableau vivant.

In restaging paintings, tableaux vivants enter into a dialogue not only with the original works of art, but also with the models who may have posed for it, creating, according to Ruiz,

“[A] shared intensity […] a bridge between the two groups of models […] The first models are in a sense reincarnated […] Certain philosophers, like Nietzsche and Klossowski, have seen an illustration or perhaps even a proof of the eternal return in such reincarnated gestures” (2005: 51)

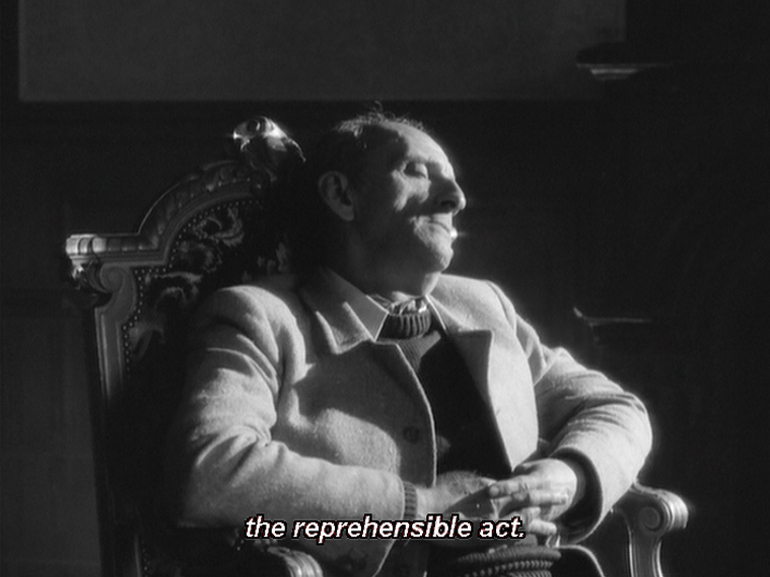

Ruiz further muses, “Some observers have seen in this juxtaposition a continuum of intensity whose effect is to erase all identity” (1995: 51)5. These concepts are figured in the speech acts between the Narrator and Collector who appear to communicate across different temporal dimensions while sharing, despite their different dispositions, an almost mystical connection. For example, when the Collector falls asleep in the middle of an elaborate explanation, the Narrator whispers his commentary, recalling Godard’s voice-over in his Two or Three Things I Know About Her (2 ou 3 choses que je sais d’elle, 1967), as if to avoid waking the Collector. When the Collector does awake a few moments later he picks up and continues on with the Narrator’s train of thought, even repeating one of the Narrator’s phrases: “reprehensible act”. This slippage of time and identity casts doubt on the notion of a unified self. Perhaps the Narrator and Collector or two aspects of the same person, or one is the reflection of the other, but at a temporal remove. This accords with Ruiz’s speculations in his Poetics of Cinema: “In this lottery of synchronisms and diachronisms, a melancholy turn of mind leads us to suggest that the world has already happened and that we are nothing but echoes” (2005: 54). It also chimes again with ideas found in the stories and essays of Borges, a writer with whom Ruiz felt a great affinity. ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’ proposes the coexistence of multiple temporalities, while ‘Borges and I’ examines the coexistence of different selves.

While the tableau vivant may be an apposite form through which to explore such conjunctions, further problematising the documentary aspect of Hypothesis is the fact that Tonnerre is, of course, a fictional character and his paintings created specifically for the film6. Indeed, Klossowski himself invented the character of Tonnerre for a 1961 essay, worthy of Borges, entitled ‘La Judith de Frédéric Tonnerre’ (2001: 120-125), in which he parodies art criticism. But the film is not only a parody of the arts documentary, or a cinematic reflection of a parody in essay form; it is also an attempt, in true documentary spirit, to get to the heart of Klossowski’s thought. What it reveals there is an aporia. Klossowski’s absence mirrors the missing painting at the heart of Hypothesis which is the motivating force behind the Collector’s exegetical activity and also a symbol of the impossibility of interpretative closure. Ruiz sums it up thus: “It’s like the horizon: once you reach the horizon, there’s still [another] horizon” (quoted in Goddard, 2013: 46). Interpretation leads not to a univocal meaning, but to the need for further interpretation. Klossowski’s absence stands as a sign for this endless process. Indeed, his name is not even mentioned in the film. Like a character in a Borges story, the real Klossowski has his identity dissolved into that of the fictional Collector, and his art work into that of his own creation, Tonnerre.

At the end of Hypothesis the Collector admits that he cannot be sure about his final interpretation of the series of paintings. “What you have seen are merely some of the ideas these paintings have inspired in me over the years’ he says. But today… a doubt assails me. And I ask myself if the effort was worthwhile”. He then leads the viewer to his front door, wandering through rooms filled with the innumerable immobile figures from the tableaux vivants who stand like statues out of Last Year at Marienbad (L’Année dernière à Marienbad, Resnais, 1961) as if he is condemned forever to this life –half awake and half adream– of interpretative endeavour. On the soundtrack, however, we are returned to the street of the film’s opening, reminding us of the ‘real’ world beyond. As Richard Peña observes, “One can return to the world of street noise at the end of Hypothesis . . . yet afterward one cannot help but sense how artificial the normal world can seem after what has just been revealed” (1990: 236). The ratiocinations of the Collector seem to colour the ‘real’ world in which they take place, leading us to conceive our reality as strange, dreamlike, pregnant with possibility.

While the narrating two voices in Hypothesis do not ‘engender images’, in the sense in which Chion’s ‘iconogenic’ speech determines the image track of the film, neither do the long stretches of narration, explanation and argumentation constitute sustained ‘noniconogenic’ speech (Chion, 2009: 396-404), since they do largely refer to the visible paintings or tableaux vivants as the basis for the discourse, the speech elaborating on the visual representation captured by the camera. This varying and complex relationship between the voice and the image track that it interacts with, lies at the stylistic heart of Ice Stories, a black-and-white film composed visually of: staged and unstaged (documentary) moving images; still photographic images of characters, objects and places related directly to the narrative; and still photographic images (by photographer Katalin Volcsanszky) of ice formations in northern landscapes and seascapes which contribute to the bleak and mysterious atmosphere. The voice-over (delivered by three different performers, who may represent five distinct characters) drives the narrative. There is no on-screen speech. As with Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962), “chronology is pulverised, time is fragmented like so many facets of a shattered crystal. The chronological continuum is flayed, shaving past, present, and future into distinct series, discontinuous and incommensurable” (Rodowick, 1997: 4). In addition to being composed of these Deleuzian ‘crystals of time’ (1989: 79) in which present and past, actual and virtual, coexist and thereby create a fundamental indeterminability or indiscernibility, the identity of the characters themselves remains indeterminable throughout, generating a narrative more abstruse than that of either La Jetée or, one of Deleuze’s touchstones for the time-image, Last Year at Marienbad.

The main plot of Ice Stories follows the journey of the male protagonist, (and principal narrator) aboard a Swedish ice-breaker toward ice-bound northern reaches (perhaps to the North Pole) where a nuclear accident has recently occurred. Even before embarking on his journey, the exact purpose of which, as well as the Narrator’s role in it, remain unclear, the Narrator suffers from a recurring nightmare in which blocks of ice threaten to crush him. On his first night aboard the ship the Narrator awakes to the sound of classical music on his radio. He attempts unsuccessfully to turn it off. Then:

“A little later, a voice that I recognised right away –it was my own voice– began recounting a confusing and threatening story. Strangely, I wasn’t surprised by this remarkable phenomenon. Quite the contrary. I followed the story with the greatest interest. While my voice recounted the story, I fell asleep”

The first of four embedded stories follows, narrated in voice-over by a different character, identifiable as such only by the quality of his voice, who recounts the story of Mathias. When Mathias realizes that he is made of ice, he decides he must get to the North Pole in order to save himself from melting and ceasing to exist as a discrete entity. Although arrangements are made for him to board the icebreaker on its voyage to the North Pole, ultimately the voice from the radio suggests that he doesn’t entirely succeed: “Each winter he is resurrected; each spring he dies”. This dissolution of identity accords with the epigraph that begins the film: an extract from one of William Blake’s letters to Thomas Butts7 describing an animistic vision in which human beings inhere in everything –in every object, animate or inanimate.

Subsequent stories transmitted through the ship’s radio to the Narrator recount several characters’ descent into madness, and the adventures of a character who, as a human guinea pig, undergoes an experiment which results in his being able to become different objects at will. In this latter case, the radio voice claims that the character “transformed himself simultaneously into an ashtray, a pipe, a coffee cup, and succeeded in disguising himself as a Swedish tub chair”. Despite the mysterious, menacing, almost apocalyptic atmosphere throughout the film, surreal scenes such as these leaven the film with a slyly comic and self-parodying tone. Significantly, the voice emanating from the radio is, like the voice of the Narrator in Hypothesis, dry and closely miked, suggesting that the voice may actually derive from the Narrator’s mind. Indeed, the radio programme begins transmitting “a little after midnight”, though the ship’s First Officer assures the Narrator that the ship’s radio terminates its transmission at 11pm. This splintering and dissolving of identity correlates with a blurring of the boundaries between reality, dream and illusion. The breakdown of causal connections casts temporality adrift, while the radio programmes, spoken by unidentifiable narrators who tell first-person stories in which they quote other characters at length, create a mise en abyme of tales within tales within tales. These narrative elements accord with the four basic devices of fantastic literature that Borges’s once outlined in a lecture: “the work within the work, the contamination of reality by dream, the voyage in time, and the double” (Irby, 1970: 18). Despite this embrace of the fantastic, Ice Stories maintains an air of realism.

Counterpointing Ruiz’s fantastic and baroque vision, the photographic images assert the documentary reality of these places, objects and people, and ground the bizarre story in our shared world. When the radio voice describes the character transforming himself into household objects, after a few moments’ delay the image track presents these objects in order they were mentioned: an ashtray, a pipe, a coffee cup, a Swedish tub chair. Though in this instance the interplay of iconogenic voice and corresponding image generates a comic effect, elsewhere the impact is disturbing. Images of desolation counterpoint the humour and hint at the real possibility of an onset of madness amidst the unpopulated inhuman world presented: the icebreaker’s bow cutting through white ice to reveal black water; huge otherworldly ice formations rising from stark white landscapes; the Narrator’s vacant cabin, with desk light and porthole; the ship’s empty corridors, empty deck and implacable, rotating radar antenna. The shot of the Narrator’s cabin (as he confesses that “a humming sound seemed to envelope [the radio voice] and that the almost imperceptible vibrations changed the colour of light in the cabin. Soon my cabin was filled with a blood red light”) is genuinely unsettling, in large part due to the mise-en-scène. The shot begins with a close-up view of a curtain which is swept aside (as if by the unseen Narrator) to reveal a low angle view of the empty cabin before the curtain is drawn closed again. Does the shot frame evidence of madness –the absence, despite the Narrator’s claims, of blood red light? The significance remains uncertain.

Elsewhere, images of the characters provide a temporary sense of orientation. When the first radio voice introduces Mathias, the utterance is accompanied on the picture track by a still image of a large, brown-haired man. A subsequent image of a short, wiry, dark-haired man appears to be the storyteller from the radio who features in his own first-person narrative about Mathias –again, this is a supposition based on the conventional filmic figure that invites the viewer to link voice and image if they occur simultaneously or in close succession. However, the image of the same small, dark-haired man features much later in another embedded narrative recounted by a different radio voice, and it is not clear whether the image is meant to represent the same person or a different one.

Nearing the end of the Narrator’s journey, when he understands “that I had a little more than a day to live” because the icebreaker “was heading straight for my brain”, he realises that he no longer needs to hear voices to take in stories; rather, “just a little noise or a burst of laugher sufficed sometimes, for me to understand the story right to the smallest detail. My cabin had become the seat of an infinity of corpuscular stories. I was breathing them”. In addition to the Narrator’s connection to an infinite network of stories, he senses his connection to the characters within the stories that have been recounted and sees his end as repeating theirs: “When I awoke the icebreaker was already there. I had arrived too. Like Mathias, like Pierre-Jean, like Paul”. The narrator’s recognition of the icebreaker’s presence brings the narrative full circle. “When I awoke the icebreaker was already there” is the first line of the film, and one of the last. The internalization of the icebreaker and the circularity of the narrative suggest the subjective nature of the Narrator’s journey –a journey into madness, or toward the dissolution of the self, or both. All of the characters may indeed be one; and the landscapes, seascapes and other objects may be features of the Narrator’s imagination. The Narrator himself becomes a witness to his own story, the dreamer who is dreamed. In his essay ‘Partial Magic in the Quixote’ Borges claims to have found the reason why such embedded stories disturb us:

“[If] the characters of a fictional work can be readers or spectators, we, its readers or spectators, can be fictitious. Carlyle observed that the history of the universe is an infinite sacred book that all men write and read and try to understand, and in which they are also written” (1970: 231)

If the characters in Ruiz’s films seduce the viewer, with their mellifluous, confessional voices, into going along with their fantastic and disorienting narratives, they also ultimately seduce themselves into listening for a little while, once more, to a story they have already recounted, or been recounted by. In attempting (perhaps endlessly) to understand something of their experience, their reality, the characters prompt viewers to question reality, to interrogate the nature of time and the basis of their own identity. Thanks to their labyrinthine narrative structures and the frequent disjunction between voice and image, the films generate radical ambiguity, polysemy. Discussing Hypothesis, Serge Daney observes:

“Certain really good films have this distinction: one ‘understands’ them (I mean that one doesn’t have the feeling of understanding nothing) only at the moment in which one sees them, in the actual experience that constitutes their vision” (1983: 24)

The perplexity that they induce, far from being just a diverting fantasy that fails to touch our world, is part of their significance and their purpose –a challenge to the viewer. Discussing the disjunction of voice and image as found in the films of Straub and Huillet, Deleuze notes:

“The voice rises, it rises, it rises, and what it speaks about passes under the naked deserted ground that the visual image was showing us, a visual image that has no direct relation to the auditory image. But what is this speech act that rises in the air while its object passes underground? Resistance. An act of resistance” (1998: 19)

With his work, Ruiz resists a positivist cinema in which films are no more than the sum of their parts and everything (or almost everything) is finally explicable. In his Poetics of Cinema, Ruiz makes clear his desire to keep alive a cinema that opposes the standardization of mainstream film industries:

“Orson Welles used to ask, ‘Why work so hard, if only to fabricate others’ dreams?’ He was an optimist and believed that the industry could dream. Accepting his postulate would mean confusing dreams with calculated, profit-hungry mythomania. Let’s be much more optimistic: even if the industry perfects itself (in its tendencies toward control), it will never be able to take over the space of uncertainty and polysemia that is essential to images –the possibility of transmitting a private world in a present time that is host to multiple pasts and futures” (2005: 121)

Ruiz emphasizes the necessity for skepticism and free thinking. Like Borges, he mystifies in order to liberate. Doubt, said Borges, is the most precious gift of all, for it opens up the possibility of dreaming. Working with a medium so closely tied to realism of one kind or another, Ruiz uses the siren song of oral narration to liberate his narratives from the necessity of causality, psychology, chronology, and to draw viewers into hypothetical worlds where the boundary between documentary reality and cinematic illusion becomes indeterminable.

ENDNOTES

1 / I am indebted to Serge Daney for this trope. In the Cahiers du Cinéma special issue on Ruiz, he notes: “‘I hold certain voice-overs in the films of Raoul Ruiz to be the most beautiful in contemporary cinema... We know that when the understanding of a film appears to depend upon voice-over, we accord it our utter and foolish trust. Voice-over is cinema’s siren song. Its grain can drive us mad, its seductiveness is immense. But at the end of the day, it’s not there to speak the truth, but to represent” (own translation) (1983: 24, emphasis in the original).

2 / In “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” Benjamin observes: “The camera introduces us to unconscious optics as does psychoanalysis to unconscious impulses” (1999: 230).

3 / According to Ruiz, it is “plausible that every image is but the image of an image, that it is translatable through all possible codes, and that this process can only culminate in new codes generating new images, themselves generative and attractive” (Ruiz 2005: 53).

4 / These epigraphs, by Victor Hugo and Pierre Klossowski, both treat the struggle of human consciousness to distinguish between ambivalent sensations and even to continue to exist.

5 / The Collectors states: “The same gestures repeated from painting to painting, loom up, in isolation, to better efface the paintings themselves and what they represent.”

6 / The Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting was originally entitled Tableaux Vivants, and would feature Klossowski himself, who had an abiding interest in the tableau vivant and in exegetical work on paintings, critiquing the tableaux. Ruiz remarked: “I wanted to show Klossowski’s philosophical system through a series of tableaux vivants which he would critique” (Ruiz in interview, Dumas 2006). Klossowski’s sudden departure from Paris just before the shoot forced Ruiz to conceive of a different film.

7 / “Swift I ran, | For they beckon'd to me, | Remote by the sea, | Saying: “Each grain of sand, | Every stone on the land, | Each rock and each hill, | Each fountain and rill, | Each herb and each tree, | Mountain, hill, earth, and sea, | Cloud, meteor, and star, | Are men seen afar.”” (Blake 1956: np)

ABSTRACT

In two documentary-inflected fiction films, The Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting (L’Hypothèse du tableau volé, 1979) and the less known short, Ice Stories (Histoires de glace, 1987), Raúl Ruiz employs oral narration, both on screen and in voice-over, to lead the viewer into labyrinthine narratives that recall in their baroque complexity the fiction of Jorge Luis Borges. While Borges grounds his stories in the real world through referencing historical times, people and places, and often uses an academic style and form to bestow an air of seriousness and rigour to his conceptual flights of fancy, Ruiz counterpoints the fantastic nature of his stories with documentary devices and images. Combined with articulate and persuasive oral narration, Ruiz creates a unique and mysterious world that marries the real with the fantastic to unsettling effect. This paper explores how Ruiz uses specifically cinematic approaches, such as unusual voice-image juxtapositions and multiple oral narrators to challenge, like Borges before him, accepted notions of time, causality and identity, and how he incorporates other art forms, such as paintings, photographs and the tableau vivant, to interrogate the boundaries of filmic form and style.

KEYWORDS

Baroque, Borges, Deleuze, Documentary, Klossowski, Ruiz, Tableau vivant, Voice-over.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BAZIN, André (1967). “The Ontology of the Photographic Image”. In What Is Cinema? (Vol. 1) (Hugh Gray, Trans.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

BENJAMIN, Walter (1999). “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”. (Harry Zorn, Trans.). In Illuminations (211-244). London: Pimlico.

BLAKE, William (1956). The Letters of William Blake. Ed. Geoffrey Keynes. New York: Macmillan. Accessed 17 November 2013. Available from: http://archive.org/stream/lettersofwilliam002199mbp/lettersofwilliam002199mbp_djvu.txt

BORGES, Jorge Luis (1970). Labyrinths. James E. Irby and Donald A. Yeats (Eds.). London: Penguin.

BORGES, Jorge Luis (1998). Jorge Luis Borges: Conversations. Richard Burgin (Ed.). University Press of Mississippi.

CHION, Michel (2009). Film, A Sound Art. (Claudia Gorbman, Trans.). New York: Columbia University Press.

DANEY, Serge (1983). “En Mangeant, En Parlant”. Cahiers du Cinéma, 345, 23-25.

DELEUZE, Gilles (1989). Cinema 2. (Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta, Trans.). London: Continuum.

DELEUZE, Gilles (1998). “Having an Idea in Cinema”. (Eleanor Kaufman, Trans.). In Eleanor Kaufman and Kevin Jon Heller (Eds.), Deleuze and Guattari: New Mappings in Politics and Philosophy (14-19). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

DUMAS, Françoise (Producer) and PRIEUR, Jérôme (Director) (2006). Raúl Ruiz: du Chili à Klossowski [Film]. France: L’Institut National de l’Audiovisuel (INA). Available from blaq out. www.blaqout.com

GALLET, Pascal-Emmanuel (Producer) and RUIZ, Raúl (Director) (1987). Histoires de glace [Film]. France: Ministère des affaires étrangères.

GODDARD, Michael (2013). The Cinema of Raúl Ruiz: Impossible Cartographies. London: Wallflower.

IRBY, James E. (1970). “Introduction”. In Labyrinths. James E. Irby and Donald A. Yeats (Eds.). London: Penguin.

KLOSSOWSKI, Pierre (2001). “La Judith de Frédéric Tonnerre”. In Patrick Mauriès (Ed.), Tableaux vivants: Essais critiques 1936-1983 (120-125). Lagny: Gallimard.

PEÑA, Richard (1990). “Borges and the New Latin American Cinema”. In Edna Aizenberg (Ed.), Borges and His Successors: The Borgesian Impact on Literature and the Arts (229-243). Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press.

RODOWICK, D.N. (1997). Gilles Deleuze’s Time Machine. Durham: Duke University Press.

RUIZ, Raúl (Director) (1978). L’Hypothèse du tableau volé [Film]. France: L’Institut National de l’Audiovisuel (INA). Available from blaq out. www.blaqout.com

RUIZ, Raúl (2005). Poetics of Cinema. (Brian Holmes, Trans.). Paris: Dis Voir.

DAVID HEINEMANN

David Heinemann is a Senior Lecturer in Film at Middlesex University. A scholar and a film practitioner, David’s publications include chapters in Rohmer et les autres (2007) and Framing Film: Cinema and the Visual Arts (2012), while his filmmaking work includes the sound design and directing of short films.

Nº 3 WORDS AS IMAGES, THE VOICE-OVER

Editorial

Manuel Garin

DOCUMENTS

As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty

Jonas Mekas

The Word Is Image

Manoel de Oliveira

Back to Voice: on Voices over, in, out, through

Serge Daney

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Sounds with Open Eyes (or Keep Describing so that I Can See Better). Interview to Rita Azevedo Gomes

Álvaro Arroba

ARTICLES

Further Remarks on Showing and Telling

Sarah Kozloff

Ars poetica. The Filmmaker's Voice.

Gonzalo de Lucas

Voices at the Altar of Mourning: Challenges, Affliction

Alfonso Crespo

Siren Song: the Narrating Voice in Two Films by Raúl Ruiz

David Heinemann

REVIEWS

Gertrud Koch. Screen Dynamics. Mapping the Borders of Cinema

Gerard Casau

Sergi Sánchez. Hacia una imagen no-tiempo. Deleuze y el cine contemporáneo

Shaila García-Catalán

Antonio Somaini. Ejzenštejn. Il cinema, le arti, il montaggio

Alan Salvadó