A CONVERSATION WITH JACKIE RAYNAL

Pierre Léon (in collaboration with Fernando Ganzo)

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

![[i]Deux fois[/i] (Jackie Raynal, 1968) img entrevistes raynal01](/cinemacomparativecinema/images/ccc02/img_entrevistes_raynal01.jpg)

Pierre Léon:Let’s talk about how you perceived the progressive change in cinema, if there finally was one, even before you began working in the field, in the 60s.

Jackie Raynal:In the beginning, I only saw films at the Cinémathèque Française. I started frequenting it when I was quite young. I went to the cinema regularly since I was 7, which distinguished me from the general public. The sensation I had was similar to that of contemplating a treasure: at the time, the high number of possibilities one could choose from as a spectator was incredible. At the time, when I watched films, I used to notice details related to changes in social customs: why elderly women kept on painting their lips, why they dressed that way. I was particularly fond of gangster films. Yet I would be lying if I were to say that I was aware of that sort of transformation in cinema in the 1960s.

I worked as a photographer at first. After that I made some films. Shortly afterwards, I began working as a film editor for Éric Rohmer. But this was unthinkable for me in those first years when I began to go to the Cinémathèque Française. You would arrive, and that afternoon Henri Langlois might tell you that the scheduled film had not arrived yet, so he would choose to show another one, but the main thing is that it was always a fantastic film. This is was a fundamental change for me, because to have the possibility to listen to Langlois, to count on his presence there, inevitably created a movement. Because Langlois would go as far as selecting his clients. When people entered the premises of the Cinémathèque, they came across a large staircase that led to the main auditorium. And, on the other side, near Langlois’s office, there was a second auditorium, a smaller one. There in front of the staircase, he would deal with the distribution: he would ask some viewers to go up, and he would accompany the others to the small auditorium. He was like Jamin, the great chef, who would serve food according to the client’s face. What’s more, Langlois could carry out this sort of ritual because he would select his programme during that very week.

Did I notice a general radicalisation at the time? God, no! I was pretty and kept quiet. I knew that I could sleep with whomever I wanted and that I could choose. It turned out I chose a great cameraman who was like a bear, and that is how I got into cinema. So in no way can I say that I broke down any barriers. I now realise that I did, but I got into this for love.

P. L.: And one day they told you ‘come and edit a film’?

J. R.: I knew how to dress well and how to behavein high society, (because at the end of the day, the film intelligentsia was a society; these were people with money, the film studios were still working then), I was asked to work as an extra in The Busybody (Le Tracassin ou Les plaisirs de la ville, Alex Joffé, 1961), starring Bourvil. Joffé’s assistant noticed me. He asked me whether I was interested in editing, whether I wanted to start to work in film. But I didn’t even know what film editing was. When I saw the Moviola, it reminded me of the sewing machines I used to use to make my own dresses, copying patterns off Marie Claire or Elle – I was never interested in the communist magazines my father used to read. Because of this, I wasn’t scared of working manually with film. For me it was like mixing fabrics.

But I didn’t think about making films. I didn’t think about the future. I didn’t have any expectations. You have to keep in mind that money was overflowing. At 18 I was offered an MG convertible. Which is unthinkable today. What I mean by this is that we lived in the moment; we didn’t think about whether we wanted to make films or how we would make them.

P. L.: In any case, going back to the issue of the radicalisation of that era, I am convinced that one is not aware of it when one is ‘living it’. You are part of that era, you're working. And, when you do this as part of a group, as is your case, everything is very casual. We only realise what it isin hindsight. So, a few years later, were you aware that the Zanzibar Group’s work left a witness to a change in perspective about cinema, or about the filmmaking process?

J. R.: It's important to speak about teamwork, seeing as with the arrival of digital film it is quite difficult to understand. We were a group of craftsmen. We worked in a process of trial and error. As an editor, for example, I needed the Foley artist's help, that is to say, someone who was in charge of recording a series of sounds to be included at the editing stage. I also needed to work directly with the camera operators. One has to try and understand what collective work was like under those circumstances. The tasks were passed on from one to the other; it's like fishing on a boat: you don’t know which way you’re heading, you work, you rest a while to smoke or drink, you get to know the people you are with, you fall in love, you see that it might bother someone else and you stop. It’s something that affects creativity; it affects the speed of the working process.

P. L.: Even though I have only shot one 35mm film, what you are talking about sounds very familiar to me. Our way of making films is very similar, even if we shoot on digital.

J. R.: In your case, this is probably due to your being a great actor, you write very well, you are a good film-maker, and cultivated. You are even capable of making a Dostoyevsky adaptation1. There is a 15-year gap between us. The Zanzibar Group was like a family: we didn’t work in a studio, but we had our means. When that family broke, things were over for me. What makes me despair, in terms of technical changes, is to have to learn anew, over and over, something I already know how to do perfectly. And this is due to the instruments, as they are increasingly smaller. It annoys me that the market imposes those changes, as we came from the tradition of Pathé, the Lumière brothers, the daguerreotype and Niépce. Your training is in theatre, you know the opera and music well. Mine comes from film. I know film the way Langlois taught it.

P. L.: It’s true. My background is above all literary. I think that all film-makers hold an inheritance from different arts in varying proportions. Now I understand what you explain better, as your origin, in terms of film, is in the very fact of manually working with the filmstrip.

J. R.: Exactly. It's like Cézanne, who said it wasn’t he who painted, but his thumb. Or Manet, who said he only painted ‘what he saw’. We mustn’t forget the impact that ‘Caméra/Stylo’, Alexandre Astruc’s text, had on us. It was an important step when the film-makers from the Nouvelle Vague understood that one could make a travelling shot using a wheelchair, and they confronted the studios with it. Sign of Leo (Le Signe du lion, Éric Rohmer, 1959) emerged out of that. It was shot entirely on naturallocations, just like Breathless (À bout de souffle, Jean-Luc Godard, 1960). For me, the great masterpieceof those years – even if it went unnoticed at the time, like The Rules of the Game (La Règle du Jeu,Jean Renoir, 1939) – was Sign of Leo, because it doesn’t let you know whether it was shot using a handheld camera or a tripod. In any case, it doesn’t matter much whilst we contemplate its beauty. All of this is comparable to Martha Graham’s democratisation of dance. And, on the other side of the ocean there was Jonas Mekas, who put into practice a way of making films that Jean Rouch only dreamed about.

F. G.: It is true that, upon reading Rouch’s writings on film, one cannot help thinking his ideas were close to what Jonas Mekas or Stan Brakhage were doing in the United States at that time. Had Jean Rouch seen their films?

J. R.: In Rouch’s case, the key was Mario Ruspoli and his idea of ‘direct cinema’. Rouch travelled less to the United States; he was more influenced by the films of Ruspoli, who was a great film-maker. In the early 1960s, when he was thinking about how to build a camera prototype that was identical to the Coutant, with synchronic sound, Ruspoli invitedAlbert Maysles over. Rouch was already there. For Ruspoli, the camera had to integrate the direct dynamics of the shoot, just like another character in the film, to the point of having the characters pass the camera on from hand to hand. This sort of film created a lot of employment. But, once again, what was fundamental was the format: because they were shot on 16mm, those films could only be screened in schools, town halls, or workers’ unions. Therefore, that film movement did not reach the bigger film theatres, as they were not equippedfor it.

F. G.: Perhaps this link could be traced down in a less direct manner, through the influence of Dziga Vertov himself.

J. R.: Yes. And Robert Kramer could have also been a link between Rouch and Mekas. Chris Marker, who only wanted to shoot in 16mm, was also important, though he was capable of shooting on 35mm very well. All these film-makers were publically committed. Our interests as a group were far closer to the ideas of Andy Warhol. In Paris, we were taken for hippies, the first factory boys and girls. All of this took place between 1967 and 1968, not before.

The members of the Zanzibar were much younger than Rohmer, who was twenty years older than me, or Godard, who is 12 years my senior. The generational difference can define everything. When I edited Rohmer’s films, I remember paying great attention to the soundtrack. I used to go to clubs and jazz clubs, record people and send him the tapes. To him, all of this was very unusual. I proposed to Rohmer that we insert these recordings in the films, as they would make them seem more modern. In The Collector (La Collectioneuse, Éric Rohmer, 1967), for example, you hear some Tibetan trumpets that I recorded. At the time, even if we worked with excellent sound engineers, an editor also took care of these matters. It was like DIY. Rohmer loved the recordings that I made in the street, which matched quite closely to the dandies in The Collector. A common practice consisted in inserting that sort of sound at a very high volume. Ambient sound shaped the film. We would work with up to 18 soundtracks.

P. L.: You made a funny connection between Rohmer and Renoir earlier on. Thinking about the idea of the double screenings... Sign of Leo begins where Boudu Saved from Drowning (Boudu sauvé des eaux, Jean Renoir, 1932) left off. The link between Renoir and Rohmer does not stand out at first, but Sign of Leo is a very violent film, so the connection between them is quite crude.

J. R.: Renoir always made his characters speak in a peculiar fashion. In The Rules of the Game there were two foreigners, something the French audience didn’t like much. In Sign of Leo, there is an American with an incredible accent. The French weren’t quite prepared for this; we mustn’t forget their anti-Americanism. But yes, as you say, the relation with Sign of Leo begins whereBoudu Saved from Drowning ends. It’s very interesting. Dreyer and Renoir were Rohmer’s favourite filmmakers.

On the other hand, one must keep in mind that at the time, a sort of split had already taken place: on the one hand, we saw films from the Nouvelle Vague on a daily basis, because we were young and we felt close to them, and, on the other hand, we continued to learn with the great American classics. André S. Labarthe used to say that film had found the formula of suspense. Cinema was the story of a high-speed train that had arrived on time.

P. L.: When you and Jean-Claude Biette started making films, in the mid 1960s, you were what Biette called ‘the critical generation’. With this he meant the films of both the Diagonale Group and of the Zanzibar Group.I would situate this generation between 1963 and Pasolini’s death.

F. G.: In fact, Biette’s critical spirit was always marked by an attempt to speak about old films as if they were new releases, and of new releases as if they were already classics. I think this started getting complicated when your generation began making films, when American films started to be seen through that critical filter.

P. L.: For Biette it was a way of continuing to affirm that there is no difference. Or that this difference is merely a historical one, not a real one. The films are alive, they can’t be tucked away in a cupboard. Biette could watch a film by Hawks as if it were a contemporary one. When a present-day critic watches a film classic, he may find it good, but to him it will always be ‘a good old film’. Why? Because critics believe in rhetoric. They are incapable of breaking away from the rhetoric of the specific era that the film carries with it. A present-day viewer can doubtlessly enjoy watching An Affair to Remember (Leo McCarey, 1957), but it is possible that he might find it too melodramatic or unrealistic. In this case, one would have to explain to him that those elements are part of a rhetoric that is specific to that era, and that they are present in all those films. It is a sort of ‘obligation of language’. If they are not capable of perforating that ‘language’ to reach the true ‘speech’ of the film, they are lost. But it is not the audience’s fault. We have to be able to distinguishwhat is part of historical rhetoric, which is often quite ‘hysterical’. In Soviet films, for example, if you are not capable of seeing this, you will not be able to understand a single film. The same goes for Hollywood classics. In any film there will inevitably be an ideology. There is one in contemporary film as well, although it isn’t the same one. In 50 years’ time, I think the audience will have great trouble understanding the American films of our time. For the same reasons.

J. R.: I remember that I didn’t go to see Frenzy (Alfred Hitchcock, 1972) when it was released. The catastrophe that was feminism had arrived during that time. For my friends, it was unconceivable that one of us might like Frenzy. It was seen as an attack on women, a film thatcompared us to dolls. And yet, later on, I watched it and realised that it was not at all aggressive in that sense. At that moment, this feminist reaction against a certain kind of cinema triggered endless comments such as ‘What are you doing watching these things? Women are naked and are murdered in the film! They’re cooking all the time!’ To be honest, I fell into the feminist ‘soup’, even if I wasn't really interested in its discourse. I was however fascinated by the feminist sublime of women like Delphine Seyrig, for example. But feminism wanted to scare men, which in my point of view caused great damage. Above all, it led to a broader marginalisation.

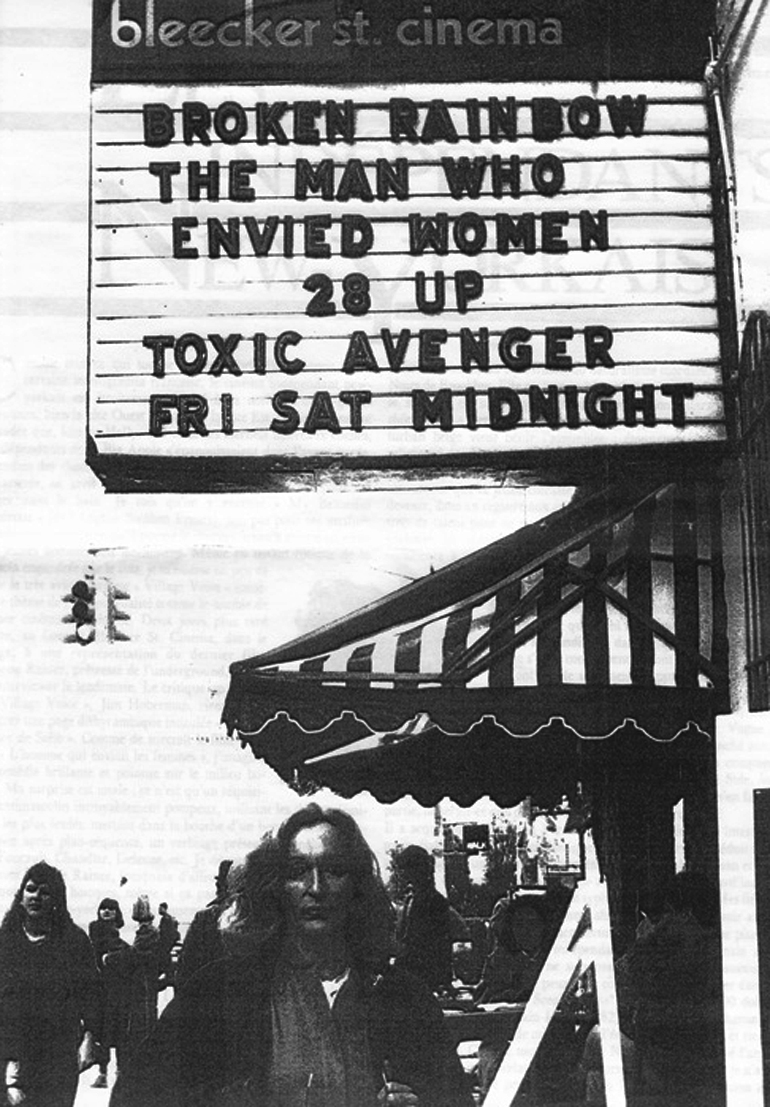

P. L.: In this sense, did you ever have any problems with Deux Fois?

![[i]Deux fois[/i] (Jackie Raynal, 1968) img entrevistes raynal02](/cinemacomparativecinema/images/ccc02/img_entrevistes_raynal02.jpg)

J. R.: As I was saying before, we weren’t going through a crisis at the time. AIDS didn’t exist either. It was a blossoming era, a golden age. On the other hand, I think that we are still in a golden age of film, even if there is one big difference: more and more films are being made, but, at the same time, there are far less film theatres to show them in, which makes everyone unhappy.

P. L.: When they asked Welles to give advice to new generations about how to make films, he always answered that if people had a television set at home, they could make their own films with it. The problem today is distribution. Distributors don’t think it’s possible to do things differently. Film-makers cannot defend themselves from that, although this argument can never be used as a reason for not making films. We make do with what we have the best we can. I am from a generation that was always between films on celluloid and the first VHS tapes – I welcomed them with much happiness. I have never tried to theorise over this change in the nature of the image. For me, you either make films or you don’t. The format is not important.

When I started making films I would sometimes react against films that impressed me, as they somehow ‘prevented’ me to think about the ones I wanted to make. Yet this didn’t happen to me with Dreyer’s films: they are so beautiful they make you want to carry out your own projects. When I discovered the Diagonale Group’s films, or those of Adolpho Arrietta, or your films, Jackie, I said to myself that I was also capable of making them. But I went for it without projecting myself socially, which is what I find most shocking at the moment. Today, youths who want to ‘make films’, want to be‘inside film’. My films had nothing to do with this ‘social’ aspect. For me, going to see films wasn’t a social practice. In 1980, Mathieu Riboulet and I picked up a camera and made a film, as simple as that. 6 years went by before I shot another film, Two Serious Ladies (Deux dames sérieuses, Pierre Léon, 1986). It was an adaptation of a novel by Jane Bowles that Louis Skorecki had lent me when we were working at Libération. It is not that common to read this book and feel the desire to shoot a film, because the novel takes place in different parts of the world. But shortly before that I had seen Winter Journey (Weiße Reise, Werner Schroeter, 1980), a story about sailors and about travels that was shot using canvases and painted walls as its only backdrop, Mèliés style. So I realised that Schroeter was right. In my film there were trips to different places in Central America by boat, so every weekend we would paint the walls of the room in order to change location. It was a simple process, almost an unconscious one. To take a step from watching a film to making one was almost natural. Afterwards I became less naïve and less interesting, because at a certain point I learned how to shoot and edit, while at the time I didn’t even know whether I needed to split up a sequence shot with another shot. Marie-Catherine Miqueau, the editor, would laugh at me when she was editing because she would say there was nothing she could do because there were no additional shots. So I learned that there are certain things you have to do in order to have various possibilities, and about the importance of editing.

J. R.: It’s interesting that you should talk about possibilities. Together with the radicalisation of Cahiers du cinéma came a socialist-communist fascism. It was so extreme that you were no longer allowed to use the shot-reverse shot, whilst before we had done whatever we pleased in that sense.

F. G.: Before Cinélutte or the Group Medvedkine, through whose members one could see a rejection of the Auteur theory, you get the feeling that Zanzibar was very different. Before you said that you felt closer to the spirit shaped by Andy Warhol around the Factory. Were you in contact with the New York community that congregated around figures such as Jonas Mekas, Ken Jacobs or P. Adams Sitney?

![[i]Acéphale[/i] (Patrick Deval, 1969) img entrevistes raynal03](/cinemacomparativecinema/images/ccc02/img_entrevistes_raynal03.jpg)

J. R.: Patrick Deval, Laurent Condominas and Alain Dister travelled to the United States in September of 1968. I did the same two months later. When Sylvina Boissonnas – who had been our patron up until then – became a feminist, she didn’t want to have anything to do with us. So I sold my apartment in Paris and used the money to maintain them, taking Sylvina’s place. We lived in this way during three years. We bought a car in San Francisco and visited all the communities, even going as far as Colorado and Mexico. Yet unlike in New York, we watched no films in San Francisco. We went to concerts to see The Who, Cream or Led Zeppelin.

In New York, Mekas, Jacobs, Sitney, Warhol or Gerard Malanda already formed a true community when we met them. As a group, they were much poorer than we were. They lived in the Bronx or in Queens. Ken Jacobs’s family was really humble. My impression was that the Zanzibar’s story was an operetta compared to theirs. By living as a community, in their own way they managed to change the world: New York was bankrupt then, so they recuperated apartments and old factories. In the areas between 38th Avenue and the edge of the city there were hardly any shops, so it was full of people squatting apartments. But life was really tough, as you can see in On the Bowery (Lionel Rogosin, 1956). A good portrait of New York in those years, where people were dying of starvation in the streets, is The Connection (Shirley Clarke, 1961). So, the way we saw it, the American movement was totally ‘demented’, but not political.

Therefore our idea of a collective, in that sense, was much more American than French. We were not that interested in the ‘engaged’ or ‘political’ aspect of the French collectives. They were, above all, left-wing groups, Maoists. We did not want to be catalogued in that way. We were part of the same ‘broth’, as our parents were communists. In fact, almost all intellectuals were communists – I could quote Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Yves Montand, Simone Signoret… But for me, it was not interesting to turn to communism or Maoism, because it had been part of my education. When I was in Rome in 1968, working on the Ciné-tracts we had shot in May, we were all tagged as hippies, as dandies driving a convertible. As to our appearance, we imitated British and American aesthetics, as we found them far more brazenthan French ones. That time in Rome was also important because the Cinecittá studios lived on there. One could find beautiful actresses such as Valérie Lagrange, Tina Aumont or Margareth Clémenti working with Pasolini or Fellini. We were interested in Italian films from that era because they were more playful than the French. You may say that the fall of French cinema after ’68 was very hard. On one occasion, I posed naked for a photo feature, after which no one would hire me, except for Rohmer. In fact, Deux fois was a big scandal. Because of it, among other things, I had to move to the United States.

In any case, if Zanzibar, as a collective, felt closer to the work of Warhol or Mekas, this was due to the fact that we had seen their films at the Cinémathèque Française. So we go back to Langlois once again; he educated us. We would go to see films on Fridays at midnight or on Sundays at eleven. And you could only see them there for the simple reason that they had been shot on 16mm. The film theatres were not equipped to project that format then. You could blow them up into 35mm, but you needed money to do that and it was very expensive.

F. G.: In an article, Louis Skorecki (SKORECI, 1977: 51-52) comments that, after Deux fois, he found it very difficult to continue working in Paris, whilst in New York the film even opened some doors for him. Our impression was that other filmmakers such as Adolpho Arrietta might have also done better in New York than in Paris.

J. R.: That is absolutely true. In Paris, the small ghetto in Le Marais could watch Arrietta’s films thanks to Jacques Robert, the great director of the film theatre. As for myself, a woman in France who was working as chief editor of the Nouvelle Vague – I mean Six in Paris (Paris vu par…, Claude Chabrol Jean Douchet, Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Daniel Pollet, Éric Rohmer, Jean Rouch, 1965) in particular –, I was not easily allowed to move onto directing. It was unacceptable for an editor to appear nude or urinating on the carpet in her own films. At the screening of Deux fois in 1968, at the Cinémathèque Française, a guy went as far as slapping me. He wanted to impress his girlfriend, who came crying to me saying ‘Why did you do this to me?’ But Rohmer and Rivette liked it, even if they never wrote about it. Daney did a little later. But it’s funny, because in the United States, indeed, it did much better. An individual who does something different is respected more, whilst the French find this irritating. Even so, I must say that in Memphis I went through another controversial experience with the film, in 1972. The viewers thought they were going to see an Andy Warhol film, a sort of ‘filming contest’ by the Zanzibar Group. The theatre was full, because Warhol films were never shown there. Doubtless, they wanted to see a depraved, harmful, film. A guy broke a beer bottle and came to attack me: ‘You are trash!’ I responded something that made everyone laugh: ‘It must be Saturday night!’

P. L.: When did you start to work as a programmer? I must point out that I detest the word ‘programme’; I find it confusing. People may think that it is a political programme, while ‘programming’ means to carry out a form of editing similar to the one Langlois put into practice: you place one film next to another and you surprise the viewer.

J. R.: I travelled to the United States to stay for good in 1973 to edit quite a big film, Saturday Night at the Baths (David Buckley, 1975). Soon after that, I was asked to make a small programme, a small carte blanche. For me it was no effort to ‘alineate’ those films. Without quite knowing what I was doing, they actually worked. For me it was like a bet, just to make some ideas emerge. It was a ‘pioneering’, ‘adventurous’ experience, keeping in mind, above all, that I had just arrived in America.

F. G.: Could you mention some of the cases when having placed one film next to another, you noticed a sort of meeting, a friction or transformation?

J. R.: I think we managed to do something like that on several occasions: to create a new meaning through the programme itself. One of the most accomplished seasons was the one on Jacques Rivette, whose films were shown together with some American films. The presence of Jonathan Rosenbaum was fundamental, as he participated in the conception of this programme, ‘Rivette in Context’2, which took place at the Bleecker in February 1979 after the book Introduction to Rivette: Texts & Interviews (1977) had been published. Rivette was greatly influenced by American films, but which ones? We needed a critic that was as dedicated as him to know that we had to see Gentlemen Prefer Blondes(Howard Hawks,1953) next to Celine and Julie go Boating (Céline et Julie vont en bâteau, Jacques Rivette, 1974), to mention one of Rivette’s films. What Rosenbaum did was highly noteworthy. It is proof that films are influenced greatly by their environment, whether it is another film, a book, or a review. It’s something we noticed in the case of the MacMahoniansin particular, as they were groups of critics or cinephiles that used to group film-makers together. In any case, you always have to look for a good ‘frame’ for a film. Because of this, when we now watch Gertrud (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1964), for example, we find it hard to understand why it wasn’t appreciated by a French audience. It was probably as a result of this issue. Sometimes, a series of common themes exist that the public might not notice are there which make us pay attention to certain elements.

F. G.: The Bleecker Street Cinema had already screened experimental films such as Flaming Creatures (1963) by Jack Smith before it was banned. How did you deal with the inheritance of the former programmes of the film theatre? What distinguished your programmes from the film seasons that were normally organised there before you arrived?

J. R.: I had seen Andy Warhol’s Sleep (1963) in that same theatre. The Bleecker Street Cinema only opened on weekends. The building was rented out by Lionel Rogosin. Rogosin distributed the main underground films from New York through Impact Films, but it stopped going well because Mekas, Rogosin and Smith split up. There was a considerable difference in class between Rogosin and Mekas or Smith, who were much poorer. Subsequently, Rogosin ended up losing his economic means and ended up programming his own films. At the beginning, the Bleecker was a ‘speakeasy’ with a mainly lesbian audience, especially during the 1930s. It used to be called Mori. In fact, there is a very famous photograph of Berenice Abbott where you can see the old building on Bleecker Street, which was built by Raymond Hood, the same man who designed the Rockefeller Center. He made this building with five Italian style columns just for fun.

In New York, both the film theatres and the audience were very diverse. If you are in charge of the programme of a theatre there, it is most important for it to be as close to downtown as possible, as that’s where the New York University, the New School and the School of Visual Arts are. This sort of audience wanted to see the films of its time, whose characters were their same age. The auditorium of the Anthology or of Bleecker Street Cinema had a very young audience. That of the Carnegie Hall was instead far more conservative. At the beginning, my husband, together with a programmer, was in charge of the latter, while I worked at the Bleecker, as I was younger than he was and knew my audience better. My auditorium was much cosier. Some beggars or fugitives would come to sleep or take refuge there.

The main thing is, an auditoriumprovides nothing unless you have many subscribers or you are ‘specialised’ in something. The MoMA or the Anthology were non-profit institutions, but the MoMA had much more money paid by members or subscribers than the Anthology. Under the law, both were obliged to show films that were not very commercial, or that weren’t particularly supported by the critics. One must remember that, in the United States, the press is far more important than advertising. American film critics can work without being afraid of being censored; they can write a very negative review of a great film without fear of repercussions. In France, on the other hand, the ‘army spirit’ prevails, they don’t want to attack their allies. In New York you knew that if Jim Hoberman defended a film you had programmed, or if the New York Times did, you would have a hit at the box office.

In this sense, the 1970s were a time for taking a stance, when disputes between magazines were commonplace, for example between Film Culture and Film Comment, to the point that those disagreements would lead to small sects. Even Mekas would come to see me to say he would beat me up if I didn’t show independent films. Surely not in those words, because Mekas was an adorable person. I set him straight and told him that, being the good daughter of Langlois that I was, I would programme all sorts of films.

P. L.: There is also a snobbish side, an aspect of ‘the happy few’ that I think is necessary, and that consists in looking for what nobody wants to see. When I discovered Women Women (Femmes femmes, Paul Vecchiali, 1974) nobody knew it. It was as if that film belonged to us. Soon after that, we travelled to the south of France to watch the rest of the Diagonale Group’s films. The taste for ‘the invisible’ changed my way of thinking, as it generated a general distrust towards anything that was successful. Marie-Claude Treilhou often says that what bothered us about commercial films was its falseness, how easy it was to unmask it. That happened to me with Clean Up (Coup de torchon, Bertrand Tavernier, 1981). I don't know whether it was a matter of intelligence, but at least it was important for thought to move. Etymologically, the word ‘intelligence’ means ‘to connect things’.

J. R.: And it’s done from the heart.

P. L.: That’s true. Perhaps that’s why I felt so close to the films by the Diagonale Group at the time. I used to read Cahiers du cinéma regularly, but there was something about its dogma that I didn’t like: the denial of psychology. They would deny that something beyond the formal or the political could exist in a film. I needed small nothings to continue to exist in films. I used to find this simple aspect in Vecchiali’s films: they might fail sometimes, but the life contained in those films was generally not directed towards formalism. For me, Jean Renoir was a sensual film-maker, whilst for Cahiers he wasn’t. I understood Hitchcock’s films when I realised that they dealt with the burningdesire that circulated between men and women. He was only interested in how a man and a woman might meet, how they might make love, how they could be together. Suspense in his films is not about the question of ‘who killed who?’, but about the meeting between man and woman. It is something I recognise in almost all of his films. You just need to think about the idea of the wife in The 39 Steps (Alfred Hitchcock, 1935). I don’t find this dimension in Fritz Lang’s films of course, so in that case I agree with Cahiers. The only film he made that was less cerebral, the most captivating one in terms of emotion, is Clash by Night (Fritz Lang, 1952). I have never seen a film with such a terrible psychological game, as the question that matters is always that of love. That is why I used to read Cahiers du cinéma, even though I kept my distance.

J. R.: In my case, I experienced the same feeling with Stephen Dwoskin’s films. I remember the day I saw his film Jesus Blood (1972). It was in a small theatre run by Langlois at the Musée de Cinéma, where he had installed a giant cushion. He used to screen films on a small screen, so that the experience of seeing them was different.

F. G.: How were film-makers such as Jean Rouch known in New York?

J. R.: Actually, they didn’t really know Jean Rouch or Jean-Daniel Pollet that well, but Truffaut was very famous. I hadn’t worked with him as an editor, but I had worked with Godard, Rohmer, or Chabrol. They were not just popular amongst more avant-garde circles or museums, but also in art house theatres, of which there were quite a few in New York. Their films were released thanks to the work of uniFrance and Truffaut, whose help I must continue to acknowledge. With Truffaut’s death came the end of what we might call ‘independent cinema’, as he used to travel to the United States quite often to interview film-makers. And he would do it without speaking a word of English, as he always managed to collaborate with a translator. Truffaut was the ‘bridge’. Now there is no one, but at the time Truffaut’s visits were very fruitful for those who screened French films, he provided a lot of publicity. He used to ask for many films to be screened in New York, especially at my film theatre.

During that time Langlois was also travelling to New York all the time, he wanted to build a cinemateque there, but the Museum of Modern Art deceived him. They must have noticed he was dangerous, that the audience might diversify. That was the time, more or less, when they began to prepare their present collection, which is about 50 years old.

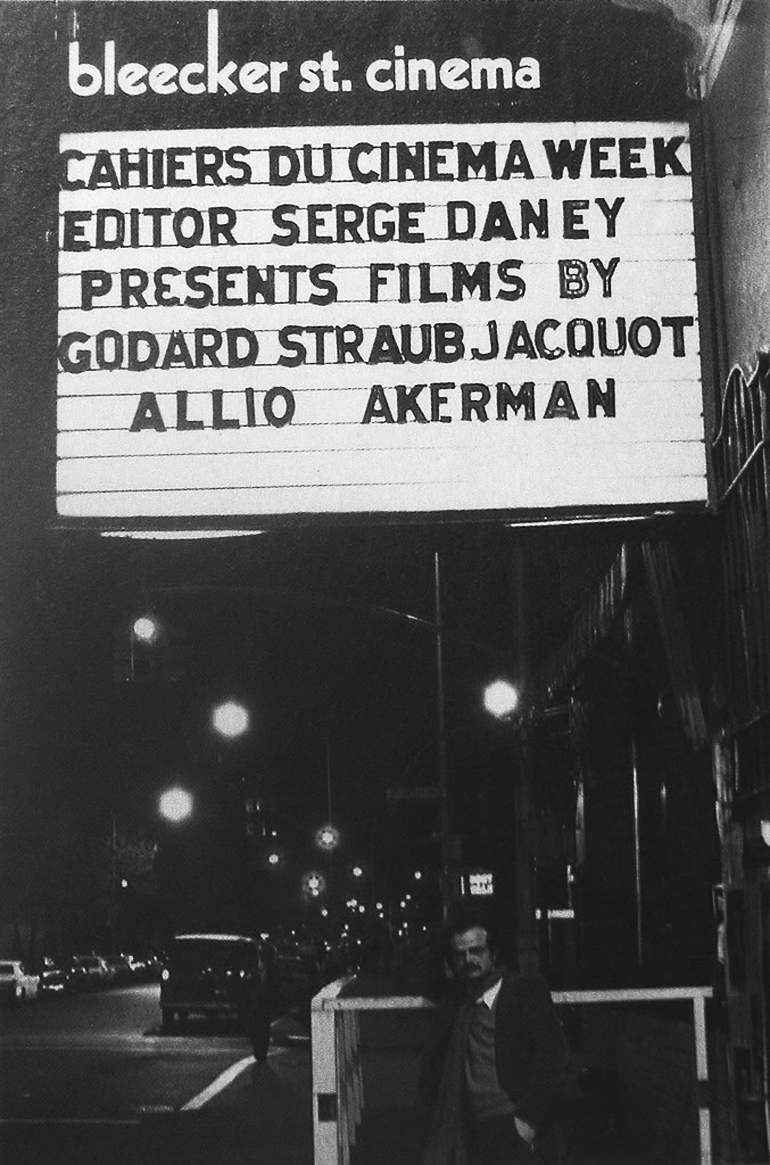

F. G.: Could you tell us a little bit about the programme Serge Daney was invited to do at the Bleecker Street Cinema in 1977? The idea, if I am correct, consisted in showing some films from the so called ‘New French Cinema’, among others Number Two, Here and Elsewhere(Número deux, Ici et ailleurs, Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin, 1976), How’s it Going? (Comment ça va?, Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville, 1978), Kings of the Road (Im Lauf der Zeit, Wim Wenders, 1975), News from Home (Chantal Akerman, 1977), The Musician Killer (L’Assasin musicien, Benoît Jacquot, 1976), Fortini/Cani(Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, 1977) and I, Pierre Rivière Having Slaughtered My Mother, My Sister And My Brother(Moi, Pierre Rivière, ayant égorgé ma mère, ma soeur et mon frère..., René Allio, 1976).

J. R.: Indeed, we showed those films within the framework of a Cahiers du cinéma programme. I yielded the theatre to the team from the magazine during two weeks in 1977. We invited Daney and Louis Skorecki. Our cinema was like a museum to us, a place where we programmed the way you would normally do in a cinemateque. Sometimes it would take us two years to conceive a programme, as New York is a very demanding city. As to the selection, Number Two was well received, once again thanks to a subterfuge: we found an unconventional way of showing it. We would sell a ticket that would be marked upon entering the auditorium, and with it the viewers could watch the film as many times as they pleased for the duration of one month. At the beginning, a large part of the audience would leave the auditorium half way through the film, but they would keep their tickets. Later, after seeing the positive feedback the film had received, especially from the press, they would return. This was my husband’s idea, which made us no money, although we did manage to cover costs. As to Straub and Huillet, it was very difficult for their films to do well. In Duras’s case, it was a little better because she had literary prestige, but her readers were not always interested in films. Rohmer’s films, on the other hand, also did rather well.

F. G.: I think that when he selected the ‘New French Cinema’ films, Daney chose some fairly ‘elevated’ films. We are not dealing with Adolpho Arrietta films here, so to speak. Yet in New York, far more ‘daring’ films were being screened. When he was interviewed by Bill Krohn (KROHN, 1977: 31), Daney said that one cannot write about ‘experimental’ films, because they work on primarysystems, in the sense that they don't need the critic’s reflections.

J. R.: And he’s right. In France hardly anyone has written about those films. I think that at the time of the surrealist movement it was still possible, but it never happened with the underground movement. In the interview with Krohn, Daney uses films by Godard and Straub as examples, while for me they were not avant-garde film-makers at all.

P. L.: I think we can accept Daney’s words about ‘experimental’ film. The problem is he decided not to show the films as part of that season. He could have considered that although it wasn't possible for him to write about those films, perhaps they could be shown. It is not compulsory to write about the films that get screened.

J. R.: Daney wasn’t really someone who programmed films for a living.

P. L.: No. His work was to write about them, to ‘talk’ about them.

J. R.: Like Jean-Claude Biette.

P. L.: Yes, but Biette showed more films. It’s normal: he showed what he made, and he made films.

J. R.: Apparently, Daney was terrified when he was faced with the shoot of Jacques Rivette. The Night Watchman (Jacques Rivette. Le veilleur, Serge Daney and Claire Denis, 1990). He told André S. Labarthe he didn’t know how to direct his team. That’s why Claire Denis intervened.

F. G.: Regarding those supposed ‘borders’, there are two ideas that I would like to discuss with you. One of them deals with an observation Langlois made, where he said that there aren’t two or three types of films, but only one, which is the perfect interaction between past and present. For him, this is what makes a film exciting. The second one is a sort of reply, by Jonas Mekas, to the question ‘what is cinema?’: ‘Cinema is cinema is cinema is…’ Do you agree with them?

J. R.: Of course. The rest are mere clichés. Nowadays we find ourselves before a different landscape; there are festivals all over the place. I get the feeling that there are no programmes overwhelming the viewer, in a good sense. These festivals design their programmes based on categories. If Mekas can reply in that way, it is partly due to having worked as a programmer in a cinema for many years. A common criticism at the time consisted in telling us off for having flyers in our auditoriums that advertised other local cinemas. They used to tell us we would spoil business, but it was the total opposite. In New York, on 46th street, one may find many different restaurants. The clients can choose which one they fancy the most, which is why the street is always packed. Our case was similar to that. We thought that the more we educated the viewers, the way Langlois did, the more they would be open to discover new films, or to share them with others.

F. G.: Jean-Luc Godard often says the history of cinema should be told from the history of the viewer. In your case, did you notice an evolution in the audience that attended your film theatre?

J. R.: Yes. To start with, the neighbourhood itself was in constant transformation, so the audience changed to the rhythm of the neighbourhood. More importantly, the way to keep a cinema like this one going, is to have an audience that ranges from 7 to 77 years old, which is almost impossible. Another very important question is to have one or several available screens. If you only have one, you can lose your entire audience with a single mistake. When I started working at the Bleecker we did made a mistake: we had a small space where we set up a bookshop, from which books were being stolen all the time, and where we barely had any customers. I realised we had to get rid of the bookshop and set up a second auditorium. In this way, we could keep a film that was doing well running for longer, such as Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (Chantal Akerman, 1975). That film was a find of ours, and a real success. But if you only had one auditorium, you were forced to screen the next film you had booked, so that someone else would take advantage of your discovery. That’s why we decided to have two screens, both at the Bleecker and at the Carnegie. The big screen at the Bleecker had 145 seats. The little one, which was called the James Agee Room, inspired by the Jacques Robert room in Paris, was equipped with 85 seats. At the beginning, to keep up our condition of a non-profit organisation, I decided to offer this auditorium to some film-makers who came with their films on Mondays and Thursdays. They would come straight ‘from the streets’ and screen what they had shot. That’s how Jim Jarmusch and Amos Poe came by.

During those years everything was connected: to get to what we called the ‘new new wave’, it was necessary for those film-makers to emerge out of the underground scene. Neighbourhood cinemas took them in and showed their films. As film-makers, Jarmusch or Poe were very much influenced by French film. There they found their audience, as there was constant movement, also in music. We used to go to a club at the end of Bleecker Street, in the suburbs, in front of the Salvation Army. I remember seeing Sid Vicious there, for example. The Blue Note was on 6th Avenue, and you could listen to rock or new and old jazz. There was constant movement around that area. The Factory was also around that quarter. Some painters also took part. Roy Lichtenstein himself used to watch films in our theatre. The interests of this movement weren’t commercial, it was just about exchanging ideas in a friendly manner. I remember that when Langlois screened films without subtitles at the Cinémathèque Française, he used to tell us that we would learn about cinema better that way. For a while I worked as a projectionist and I realised he was right. Sometimes, when you watch a film without sound, you are far more aware of how it has been made, especially if you see the audience’s reaction from the projection booth. Overall, I think that when things are overly organised, it is detrimental for the arts: you cannot make art with too much order.

My process consisted in programming and stopping once in a while to make small films. During those brief intervals I would be replaced by another programmer. At the time we had no fear. I really like the English expression ‘to dare’. It was like leaving a restaurant without paying. It consisted in taking risks, something which has been lost completely as a result of consumerism.

Translated by Alex Reynolds

FOOTNOTES

1 / A reference to The Idiot (L'Idiot, Pierre Léon, 2008).

2 / See Jonathan Rosenbaum's article in the first issue of Cinema Comparat/ive Cinema about this series. See here .

ABSTRACT

This conversation between two film-makers belonging navigates the progressive changes of cinema as lived by Jackie Raynal since the 1960s (her education, Langlois’s programmes, her experience Turing the period of radicalisation, the so-called ‘critical generation’, the creation and development of the Group Zanzibar, collective forms of working), which are set in relationship to the experience of Pierre Léon since the 1980s. In addition, Raynal and Léon discuss the work of film-makers such as Jean Rouch or Mario Ruspoli and the relationship of ‘direct cinema’ to New American Cinema, the link Renoir-Rohmer, the transformation of ‘language’ in ‘idiom’ in relationship to classical cinema and its reception at the time, feminism and the reaction to Deus foix, collectives’ such as Medvedkine or Cinélutte vs. Zanzibar, the differences between the New York underground (Warhol, Jacobs, Malanga) and the French one (Deval, Arrietta, Bard) and, finally, the work of Raynal as film programmer alter leaving Paris and the Zanzibar Group, at the Bleecker St. Cinema, tackling issues such as the evolution of the audience in that venue, the different positions of American and French criticism, the programmes ‘Rivette in Context’ (Rosenbaum) and ‘New French Cinema’ (Daney and Skorecki) or the differences in the role of the ‘passeur’ of the critic and the programmer.

KEYWORDS

“Critical generation”, Langlois, programming, Group Zanzibar, collective forms of working, underground, aesthetic radicalization, evolution of the audience, Andy Warhol, Jean Rouch.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AZOURY, Philippe (2001). Un Zeste de Zanzibar. Libération. 6th of June.

DANEY, Serge (1982). Portrait de Jackie Raynal. Cahiers du cinéma, nº 334-335, April, 1982.

HIGGINS, Lynn A. (2002). Souvenirs d’un femme dans le cinéma français. L’Esprit Créateur, vol. XLII, nº 1, spring, p. 9-27.

HOBERMAN, J. (1982), Heroes and Villains in the arts. Village Voice, 30th of December.

KROHN, Bill (1977). Les Cahiers du cinéma 1968-1977: Interview with Serge Daney. New York. The Thousand Eyes, nº 2, p. 31.

MARTIN, Adrian (2001). The Experimental Night : Jackie Raynal’s Deux fois. BRENEZ, Nicole y LEBRAT, Christian (Ed.), Jeune, dure et pure ! Une histoire du cinéma d’avant-garde et expérimental en France (p. 306-308). Milan/París: Mazotta/Cinémathèque Française.

NOGUEZ, Dominique (1982). Jackie Raynal. NOGUEZ, Dominique (ed.), Trente Ans de cinéma expérimental en France (1950-1980). París: Acref.

RAYNAL, Jackie (2001). Entretien avec Jackie Raynal. Journal Trimestriel d’informations sur l’Art Contemporain, n.1, p. 54-56.

RAYNAL, Jackie (2000). Le Groupe Zanzibar. BRENEZ, Nicole y LEBRAT, Christian (Ed.), Jeune, Dure et Pure ! : une histoire du cinéma d'avant-garde et expérimental en France (p. 299-300). Milan/París: Mazotta/Cinémathèque Française.

RAYNAL, Jackie (1980-1981). The Difficult Task of Being a Filmmaker. Idiolects, nº 9/10, winter, 1980-81.

REITER, Elfi (2006). Jackie Raynal: Il mio cinema mutante. Alias. Suplemento del diario Il Manifiesto. Saturday 7th of January, p. 16-17.

ROSENBAUM, Jonathan (1983). Interview of Jackie Raynal. ROSENBAUM, Jonathan (ed.), Film: The Front Line (p. 154-162). Denver, Colorado: Arden Press.

SHAFTO, Sally (2007). Les films Zanzibar et les dandys de Mai 1968. Paris. Paris Experimental.

SKORECKI, Louis (1977), Semaine des Cahiers : Deux Fois. Cahiers du cinéma, n. 276, May, p. 51-52.

TAUBIN, Amy (1980). Jackie Raynal. The Soho News. 24th of September, p. 31.

PIERRE LÉON

Born in 1959 in Moscow, residing in Paris, the film-maker Pierre Léon is also a member of the editorial board of Trafic. He made his first official feature film in 1994. He also stands out as an actor in the works of other film-makers such as Bertrand Bonello, Serge Bozon, or Jean-Paul Civeyrac.As a critic, after training at the Libération newspaper (together with Serge Daney and Louis Skorecki), as well as in Trafic, his texts were published in other publications such as Vertigo, or Archipiélago and Lumière from Spain. He teaches film direction at the Parisian school La Femis, and also gives conferences often about cinema in Paris, Lisbon and Moscow. His work as a singer joined his film work in 2010 at the Pompidou Centre, when a found footage film of his was projected over his own live concert, titled Notre Brecht. He is currently writing a monograph about Jean-Claude Biette.

Nº 2 FORMS IN REVOLUTION

Editorial

Gonzalo de Lucas

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

The Power of Political, Militant, 'Leftist' Cinema. Interview with Jacques Rancière

Javier Bassas Vila

A conversation with Jackie Raynal

Pierre Léon (in collaboration with Fernando Ganzo)

Interview with Ken and Flo Jacobs. Part 1: Interruptions

David Phelps

ARTICLES

EXPRMNTL: an Expnded Festival. Programming and Polemics at EXPRMNTL 4, Knokke-le-Zoute, 1967

Xavier Garcia Bardon

The Wondrous 60s: an e-mail exchange between Miguel Marías and Peter von Bagh

Miguel Marías and Peter von Bagh

Paradoxes of the Nouvelle Vague

Marcos Uzal

REVIEWS

Glòria Salvadó Corretger: Spectres of Contemporary Portuguese Cinema: History and Ghost in the Images

Miguel Armas

Rithy Panh (in collaboration with Christophe Bataille): La eliminación

Alfonso Crespo