RAINER WERNER FASSBINDER1

Manny Farber & Patricia Patterson

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

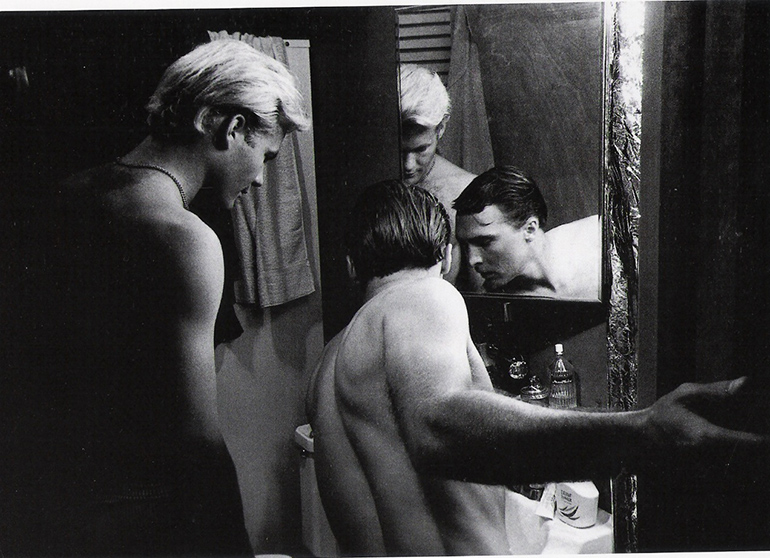

Bottom: Faustrecht der Freiheit (R.W. Fassbinder, 1975)

I’s interesting that the true inheritors of early Warhol, the Warhol of Chelsea Girls and My Hustler, are in Munich, whereas the new Warhol-Morrissey film has gone west, i.e. Heat is a Zap comic book Sunset Boulevard and Frankenstein is a salacious child’s version of the James Whale classic. Warhol’s idea of a counter-mainstream has to do with reversing the conventions of high-low art rejecting with a giggle Greenberg’s edicts formerly considered on a par with the Ten Commandments: the artist as a moral superior, integrity of the painting surface over illusion, the relationship of the picture’s inside to the edge, the high-vs.-kitsch polarities.

Like Genet’s polemical stand for the beauty of crime and perversity, Warhol proclaims the wondrousness of monotony, banality, machine-made art, expedience, and an easy mobility from one medium to another. He’s a great mover towards facetiousness and flexibility: it’s not that he doesn’t work like a bearcat at his dozen professions, but that he tries to imprint a not-that-taxing air into each new painting-print-film-interview.

By osmosis, Warhol’s kinkiness made a big dent in the Bavarian beer-bratwurst-Bach film capital, Munich. Probably few of the Munichers have seen any Warhol, but the latter’s Bike Boy, Chelsea Girls are neighbors under the skin to some of the reel wheels in TV-supported Munich films, particularly Fassbinder’s anti-cinema. There is the same painterly ability to hit innocent, insolent colors, using flat, boldly simple formats; Warhol’s image is more porous, coarse-grained, while Fassbinder’s has a sardonic, fairytale look. The Tartar-faced writer-director-actor has done one film a week (practically) since 1971, which is up to the early Warhol pace, and, in the background of Fassbinder’s image, there is the sense of grifters and bootlegging, plus the effect in early Warhol of being tough and able to control such anarchy. Fassbinder’s Marxist world unchained is compressed and delineated; you know where each form, idea, and narrative sequence starts and stops.

A henpecked boob beats up his wife in a bedroom tableau which stays on screen without camera change until the remorseless ending, the husband rolling over in a drunken stupor. The agonized, frustrated drunk beating up his selfish, penny-pinching wife is the oldest scene in movies, going back to Greed, but this fully-lit, futile explosion in a 1971 Munich movie is a remarkable blend of charm and ferocity. Aimed against prissy, middle-class taste, the purple overstatements recall Written on the Wind and another Sirk, All That Heaven Allows, which he draws on more explicitly in the 1974 Fear Eats the Soul. But the cool and very contemporary candidness suggests Warhol’s deadpan on the androgynous underworld.

A minor example of Fassbinder paralleling Warhol: the presence of Viva’s cloying, nasal whine in Irm Hermann’s startling portrait of a peddler’s sneaky wife in Fassbinder’s The Merchant of Four Seasons. In this portrait, which moves back and forth from thin-lipped petty conventionality to moments of sensuality and spunk, the mocking drawl of Warhol’s superstar combines with the lower-class traits out of another world. It’s like joining the “liberated” Soho with the corner-cutting uniformity of J. C. Penney. Hermann’s squinty eyes behind dowdy glasses, her spectacularly lean body inside frumpy, printed housedresses. Fassbinder is not the only member of Germany’s re-awakened film scene to be in a curious congruency with Warhol’s filmic investigations: his gorgeous hermaphrodites (Schroeter), put-on freakiness (Herzog), the preci-sionist long takes on a seemingly unseductive scene (Straub), but he’s the one we’re going to deal with here.

Fassbinder’s a mixture of enfant terrible, burgher, and pimp, whose twenty-four features (since 1967) are mainly sprung out of a camp sensibility. All of his appetites (for the outlandish, vulgar, and banal in matters of taste, the use of old movie conventions, a no-sweat approach to making movies, moving easily from one medium to another, the element of facetiousness and play in terms of style) are those of camp and/or Warhol. The point—to dethrone the serious, to make artifice and theatricality an ideal—is evident in an amazing vivacity, re-introducing Fable into a Hollywood gente, while suggesting a tough facile guy manipulating a deck of cards. Warhol’s ace move, taking anyone and making her a superstar, draping her in glamour and incandescence, is also Fassbinder’s. The same three leggy females appear in most films; Hanna Schygulla, a halo around her M every frame, is the ravishing beauty, the trump or tramp card in his films.

Merchant of Four Seasons (the down-path of a family black sheep, who goes through a Dreiserian list of humiliations, and then, as he’s beginning to make h some headway and breadway as a fruit-and-vegetable hawker, he methodically drinks himself to death) is a luminous, inventive movie that s so damn clear about its aims and means. The basic idea—the silent group pressure which causes people to come through with conventional emotions and behavior, so that every moment gets compromised and discolored has never before been pinned down so subtly and constantly. It’s not the sodden story of a downtrodden, henpecked husband but a hard portrait of middle-class ritual, circa 1972. People take turns being mean and exploitative in a musical chairs of victor and victim. As in all his films, Fassbinder is pushing melodrama to absurd limits to show how its cliché attitudes and emotions discolor normal situations.

The Merchant is the work of a medieval illuminator who has a command of visual ornateness, suggesting the most famous of hand-painted books: the Duc de Berry’s Book of Hours. Its radiant people are faced close to the camera, in what always seems a peak moment. The scene is shadowless, intensely lit. It has the ecstatic tenderness of Fra Angelico but the archetypical characters (the greedy wife, generous sister, the innocent daughter, mean-stingy mother, a sychophantic brother-in-law) are played by an acting troupe of vivid dynamic hipsters. Fassbinder makes a wholesome frontal image, in many ways like small Fra Angelico panels: a man in a crisp blue-and-white-plaid shirt hawking the pale green pears filling a rectangular cart, a humble action froten in a shallow-still composition. This unconquering hero sells only three bags of pears during the movie.

Like a cat burglar feeling out the combination lock on a safe, Fassbinder keeps turning the knob on a character, working parsimoniousness with lust-fulness in Irn Hermann’s wife, compassion and cold-blooded frankness in Schygulla’s sister, who sticks by the peddler against his disapproving family and stands for integrity. The clear individualizing and silhouetting of each character are emblematic of Fassbinder’s hermetic formalism, even when there is a reverse twist in every major character. A woman who had heretofore been all tightness is suddenly exposed in all her white length, being serviced from the rear by a stranger whose doy smirk is hung on until its meaning is in your brain.

His tough-tender vision is expressed through ritual, whether the film is a Death in Venice story (Petra von Kant) or a working-class Babbitt gone berserk (Why Does Herr R. Run Amok?). Whether the filmed event is Petra’s hypocritical phoning, Herr R.’s pompous tutoring of his little son, the Ali-Emmi dance that opens and closes Fear, these rituals serve to keep the world in place; other rituals--Hans’s evening round of drinks with his buddies—freak them out.

His ritualized syntax could be outlined this way:

(1) He inserts violence and tension beneath stupefyingly mundane talk in The Merchant: “Gee Hans, what a success you are now,” or extreme sentimentality in Fear: “Emmi, you not an old woman, you a big heart,” or the chest-beating Susan Hayward–style in Petra: “I can’t live without her, I can’t bear it,” as she rolls around un a terrycloth rug, hugging a Jack Daniels bottle to her breast. She also screams at her daughter and mother: “Go home, you bores, I can’t stand the sight of you, I want Karin!”.

(2) Acting in the Petra film is feverishly singular. As in Noh theater, it’s proto-artificial and always trying for the emblematic joined with the rich effect of a sausage bursting its casing. Petra and her monosyllabic assistant, in black Edwardian gowns, are pugnacious with their personas.

(3) From the endless yammering of Petra, who runs a dress career from her bed, to the tense, spoken opera in Fear, it’s always musical incantation. “Come borne, Hans, please come borne,” and he throws a chair at his wife’s poised body half-hidden behind the saloon door. Hermann’s porcelain skin, ruby lips, tightly curled hair has the same iconic impact as her pleading intonation. His whole acting team—Hirschmüller’s peddler, Carstensen’s designer-heroine, Brigitte Mira’s Emmi—use language for the same taunting purpose, as in the arch fox-trot by the two long-gowned women in Petra. Dancing to “Oh Yes, I’m the Great Pretender,” they never look at each other, which points again to his trademark belief in power struggles incessantly waged.

(4) He and Kurt Raab (“the design is done for me by Raab, the guy who plays Herr R. 1 tell him what I need; every color is carefully thought out, each image is worked on.”) are extraordinary inventors with captive settings—furniture, décor, people have a captured-inside-a-doll’s-house feeling. The prime factor in his syntax: the pulí between characters and their diminutive, dollhouse environment. Wife-child-husband around table eating baloney-cheese is a scene out of Beatrix Potter, people too big for tidy-tiny repetitive existence.

(5) Dress and decor: each character has his own type of clothes; Hans wears plaids, Erna dresses like a Hawks heroine, Petra’s mute assistant (played as a studied slow dance by Irm Hermann) is always in black, a sepulchral creature whose incredible curtain scene (slowly suitcasing her wooden mannequins and taking off in a tense, extended silence) is a lovely example of power infighting between two deity-like personages. Fassbinder’s very eclectic: his people stand before beautiful wallpaper like Xmas lights, mixing styles and eras within the same tableau.

A P. T. Barnum using workers and shopkeepers for his entertainers and making them as luminous and exotic as candelabras, he is actually all over the map with a playful larceny. He has taken a number of tactics from the Sirk melodramas (the flamboyant lighting, designing décor and costumes that indelibly imprint a character’s social strata, being patient with actors and playing all the movie’s elements into them, backing your dime-store story and soap-opera characters all the way) and stapled Sirk’s lurid whirlwind into a near silent film style which is punctuated with terse noun-verb testiness. A good example is tense response to a sultry hellcat’s proposition: “Cock’s bust.”

Bresson’s visual economy (the delayed reactions by the camera and actor, hanging on walls, doorknobs, or a peasant’s numb expression) is turned into very prominent rituals.

After having said all this, the fact is that Fassbinder’s intense shadowless image is not like anyone else’s, and his movies have installed the workers’ milieu—their homes, love affairs, family relations, the wallpaper, knickknacks, the slang, food and drink, the camaraderie—as a viable subject for the Seven-ties. Whether the filmed event is a fruit vendor yelling downstairs for his departed wife, or the fascistic business calls that transpire on the outsized brass bed where a yammering dress designer eats, works, and loves (the only males in sight being the gigantic nudes on the mural behind her bed), the scene most often plays in one take, without development, so that his trademark, saftig feistiness, the up-front pugnacity, always hits with more meat than you expect, it claws you with churlish aggressions.

A nosy neighbor spitefully watches the middle-aged Emmi and the hand-some black Ali go up to her apartment. In this typical tableau a rack-focus shot suggests all three, like all Fassbinder’s denizens, are caught in a shifting but nevertheless painful power game of top dogs and underdogs. The scene is dominated by aggressive decisions about décor and motivations; the camera, positioned directly behind the neighbor’s helmet-like black hairdo, pins the Emmi-Ali lovers behind an ornate iron screen that points up a tasteless magistrate and two rather gentle rule-breakers. The methodically worked-on event displays Fassbinder’s radical mix of snarl and decoration.

His strategies often indicate a study of porn movies, how to get an expanse of flesh across screen with the bluntest impact and the least footage. With his cool-eyed use of Brecht’s alienation effects, awkward positioning, and a reductive mind that goes straight to the point, he manages to imprint a startling kinky sex without futzing around in the Bertolucci Last Tango style. Style is everything in these blunt, motionless tableaux: there is a cunning sense of how much space to place between the candid sexuality and the camera, how much lurid, ersatz color needed to give the act a kinky rawness. He seems able to cue you into the licentious effect of a Thirties film, and still hold the scene in the Seventies by the stylized abandon of his ruthlessly installed temptresses. The lustfulness of Hermann’s long scrawny Hausfrau, the blow-job on Hans, and particularly Hanna Schygulla’s lazy opportunistic lesbian in Petra von Kant. She walks with her hips stuck out in a slow insinuation as drawling as her talk. There is nothing more kinky than her love scenes in a sheet-metal slave costume.

Fear Eats the Soul: the marriage between a sixty-year-old charwoman, the widow of a Nazi, and a splendid Moroccan column of muscle is endangered because Emmi won’t make couscous for Ali. Given all the possible problems that such a marital miss-match could incur, it shows Fassbinder’s perversity that he drives them apart with a cracked wheat stew. Emmi, becoming chauvinistic and complacent, tells this catch of the century to go get his couscous elsewhere. The circular structure evolves back and forth between the Asphalt Pub, a hangout for Moroccan pals, their bosomy gals, and Emmi’s cozy flat, subjecting the pair to endless prejudice bouts with the grocer, maitre d’, that bitch who patrols the hallway, her gross beer-drinking layabout son-in-law (played by the snarling camp-elion himself: Rainer Werner F.). This endless series of trivia gates overlorded by bigoted high priests causes Ali’s stomach to rip. Fassbinder, who looks like a Vegas blackjack dealer, knows how to get the effects he wants: he turns this sweet-sauerkraut into a double-edged enthralling movie.

In Why Does Herr R. Run Amok?, the light is blasting, the sound of people conversing is early TV play in its grating, granular stridency, and the plot develops an accurate catalog of comment in the daily round. A draughtsman, Herr R., dully moves through a measured tedium, until one night while his glazed eyes are on the TV and his wife and a friendly neighbor chatter along with the TV sound, he picks up an alabaster vase, kilts wife-child-neighbor. The next morning his amenable colleagues find him hanging from a latch in the office lavatory.

Scenes like the two friends talking of school songs on a funny little sofa look like comic strip: the Katzenjammers, Major Hoople. This crackup of a petty bourgeois done in raw presentation catches most of what Fassbinder is about.

(1) Humiliation; daily, hour by hour, in the shop, at breakfast, humiliation everywhere.

(2) The shopkeepers of life treated without condescension or impatience.

(3) Physical and spiritual discomfort: The essence of Fassbinder is a nagging physical discomfort.

So Fassbinder has two sides, the operatic and the forthright brash. In moving from the low-budget, avant-garde movie to large TV-financed films (“1 am a German making films for the German audience”), he has always retained a hatred of dubbed dialogue and holds to a theatrical premise, a few characters interacting in a stage space, which keeps his image shallow and makes it easier to do sync sound. What an image! His is the precision of a painter with space and color: he has a fantastic painter’s eye (he’s Mondrian with a sly funk twist) and knows how to angle a body, how much space is necessary to set it off. But his movie sails home on its lighting-color-pattern, a frontal, geometric poise that should make any hip painter envious. Someday we should love to see the early grainy black Fassbinders—Katzelmacher, The American Soldier, Love Is Colder Than Death, etc.—which have come to this coast only once via Tom Luddy’s single-handed championing at the Archive.

ENDNOTES

1 / This article was originally published in City, July 27, 1975; Film Comment, November-December 1975 (as “Fassbinder”) and collected in: FARBER, Manny (1998). Negative Space. Manny Farber on the Movies. Expanded Edition. New York. Da Capo Press; FARBER, Manny (2009). Farber on Film. The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber. POLITO, Robert (Ed.). New York. The Library of America. To preserve the original text we don’t regularize or otherwise standardize the conventions used in the article. Copyright © 2009 by The Estate of Manny Farber. Deep thanks to Patricia Patterson for permission to reproduce this article.

Nº 4 MANNY FARBER: SYSTEMS OF MOVEMENT

Editorial

Gonzalo de Lucas

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEW

The Law of the Frame

Jean-Pierre Gorin & Kent Jones

DOCUMENTS. 4 ARTICLES BY FARBER

The Gimp

Manny Farber

Ozu's Films

Manny Farber

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Manny Farber & Patricia Patterson

Nearer My Agee to Thee (1965)

Manny Farber

DOCUMENTS. INTRODUCTIONS TO MANNY FARBER

Introduction to 'White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art and Other Writings on Film'

José Luis Guarner

Termite Makes Right. The Subterranean Criticism of Manny Farber

Jim Hoberman

Preface to 'Negative Space'

Robert Walsh

Other Roads, Other Tracks

Robert Polito

The Filmic Space According to Farber

Patrice Rollet

ARTICLES

Hybrid: Our Lives Together

Robert Walsh

The Dramaturgy of Presence

Albert Serra

The Kind Liar. Some Issues Around Film Criticism Based on the Case Farber/Agee/Schefer

Murielle Joudet

The Termites of Farber: The Image on the Limits of the Craft

Carolina Sourdis

Popcorn and Godard: The Film Criticism of Manny Farber

Andrew Dickos

REVIEW

Coral Cruz. Imágenes narradas. Cómo hacer visible lo invisible en un guión de cine.

Clara Roquet