THE TERMITS OF FARBER: THE IMAGE ON THE LIMITS OF THE CRAFT

Carolina Sourdis

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / ENDNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / ENDNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

French cinema is very strong on experience, on the existential, and quite weak on the spectacular. That’s the way it is. What makes French cinema unique is unsummarisable films, works that appear to be pages torn from logbooks or intimate diaries, and a preference for black-and-white and voice-over.

Serge Daney

L’Enfant secret de Philippe Garrel, Libération, 19 February 1983

Me, I am the field (absent, virtual); the counter-field, is everything that is filmed.

Johan Van der Keuken

L’Oeil au-dessus du puits: deux conversations avec Johan van der Keuken, 2000

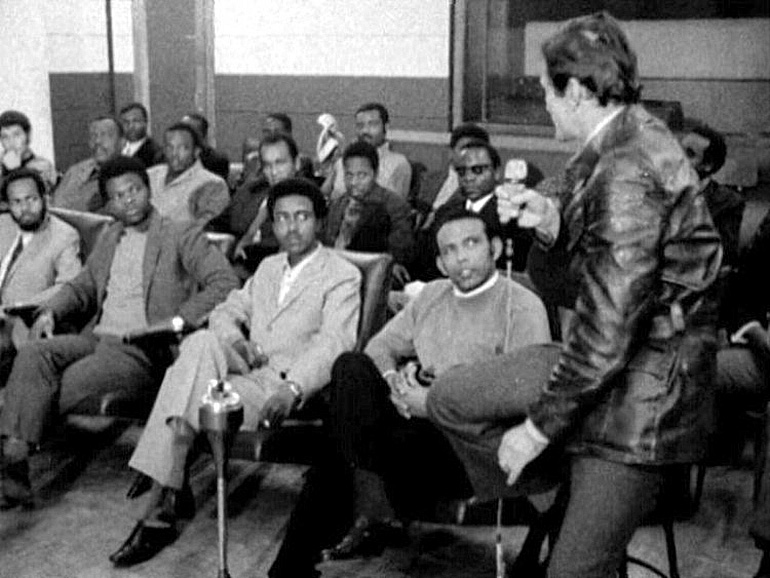

Bottom: Appunti per un'Orestiade africana (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1970)

In The Movie Art (FARBER, 2009: 33), an article published in 1942, Manny Farber forcefully rejected a statement of the Russian playwright Elmer Rice, regarding cinematic technique. Rice considered that films, synthetic in their construction and subjected to the ‘technological paraphernalia for its production’ (FARBER, 2009:33), were immersed in a ‘protracted infancy’ that would never allow them to print ‘the human breath and the human thumbprints that characterize all great works of art’ (FARBER, 2009: 33). Instead, Faber considered that the mechanics of each artistic medium were exactly the way to delimit the nature of its form. Hence, if painting had to express ‘without time and sound, writing without colour and line’ (FARBER, 2009: 33), or cinema without that particular seal of the artist1, these limitations did not correspond to a weakness at all. Instead, they were considered as a place to set the specific, the very own, the most obvious virtues of each media. As Farber writes in his article, ‘the very boundaries of an art produce its most basic advantages’.

The limits of cinema, it is evident, are deeply engaged to the technical development of the creation tools. Dziga Vertov’s creations around ‘cine-eye’ were based on the mechanical potential of the filmic media to define an expressive field specific to the cinematic arts; On his behalf, Jean Rouch required to develop different sound recording systems, to better connect the shooting and editing moments in the production of his films2. Until what point the mechanic potential of the camera, the sound recording or the editing are taken, or in which ways they condition the production methods and how the filmmaker proposes to extend these possibilities: all these have determined the images that are possible through the filmic matters. Though the industrial production model, as Rice pointed out in his judgment, set an irrefutable distance between author and work, great part of modern and contemporary cinema has been wrought upon the emphatic persistence to overcome that distance, with the constant attempt of the filmmaker to find a form to appropriate this cumbersome paraphernalia.

The attempt to appropriate the technique necessarily tends to an essayist drift. It is about testing, experimenting with the potentials of the resources available in the filmic creation. In the first sequences of Chronicle of a Summer (Chronique d’un été, Edgar Morin and Jean Rouch, 1960) and The Human Pyramid (La Pyramide Humaine, Jean Rouch, 1961), Jean Rouch himself argues in front of the camera with the characters, the motivations and intentions they purpose with the film they are about to shoot –that in fact they are already shooting–. The film is discussed as if it was an experiment. Will it be possible to make it as they imagine it? Will they be able to record a conversation as spontaneous as if the camera was not present? They will have to try by shooting the movie, or better, by filming the shooting of the movie. Hence, the value of a finished, completely solved image, is displaced by the presentation of the creation process, the search, the attempt. In Notes towards an African Orestes (Appunti per un’Orestiade africana, Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1970), Pasolini includes as a vital counterpoint of his journey registrations, a debate with some African students residents in Rome, despite the majority of them definitely disapprove his idea of adapting The Oresteia in postcolonial Africa. In this case, to highlight the dissention as part of the proposition becomes a strategy to determine the nature of the film as an essay, literally by testing forms and ways of nailing down the cinematic image.

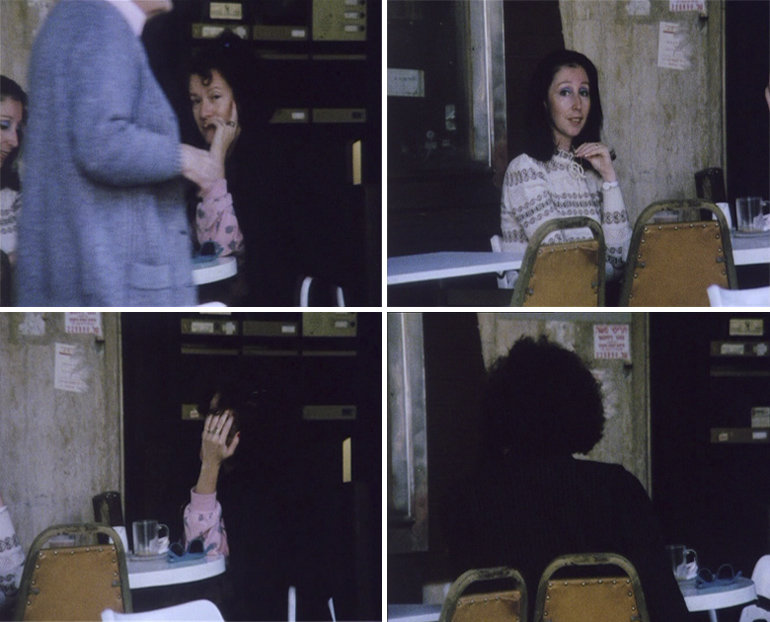

‘Beauty and ugliness still don’t affect me: it is only in the gestures that I find sometimes an interest. At the Polish Café, I don’t even hear their voices, their language’, David Perlov comments on the second part of Diary (1973-83), over several faces, shot in acoffee shop, insistently going back to the shot of two women who have a conversation far away from the camera: ‘It is like drawing a rough draft’, he continues. Between the camera movement, back and forth from one to another, one of the women notices his presence: They are being filmed. What for? They seem to question with their look to the camera. One of them, shyly, starts to cover her face with her hands, while the other one shows her discomfort staring directly to the lens. ‘These tow girls. I enjoy looking at them. They are natural. I want to watch them more and more’. The woman that was covering her face, changes her place to sit in front of the other, completely blocking with her back, from the viewpoint of the camera, the face, the look, the gestures of the other. To capture that spontaneous moment becomes impossible, the attempt of the filmmaker to ‘start filming the faces again’ as was said at the beginning of the sequence, clearly fails.

This idea of the possibility to ‘test’ with cinema is deeply connected with Manny Farber’s formulations on White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art (FARBER, 2009: 533-541). The conception of art as a field in tension between two forces; one fixed, rusted and unbreakable canonical tradition (the white elephant) and the other, a free, random and undetermined deployment of the medium of each artistic expression (the termites), insists on the necessity to bring closer, in a kind of a poetic of the materials, the end with the process. Farber writes in his essay: ‘The most inclusive description of art is that, termite like, it feels its way through walls of particularization, with no sign that the artist has any object in mind other than eating away the immediate boundaries of his art, and turning this boundaries into conditions of the next achievement’ (FARBER, 1971: 65).

This statement, demands us to stop –if referred to painting– between the amalgam of inert strokes Farber perceived in Cezanne’s canvas, to discover the ‘jarring excitment’ (FARBER, 2009: 534) of certain particles, of certain moments of matter deployment with no intention. In relation to cinema, Farber observes that same insistence on the detail, in two aspects always pushing against the simple and anti-cinematic component of storytelling3. These are, the plastic potential of the moving image as an autonomous element from the plot, and the observation of the actors, not in their performance assessed on their dramatic intensity, nor regarding the role they interpret, but rather on their vital presence on screen, concentrated in ‘those tiny, mysterious interaction between the actors and the scene that make up the memorable moments of any good film’ (FARBER, 2009: 542). Even in his earliest critical production, Farber already makes a definitive distinction between actor and character, appreciating above all, the undeniable presence of the body of the performers4, that component of ‘truth’ that came out of the film records5. This might be the reason why he tended to relate the termite-like tendency in cinema, mostly with the actors technique.

However, Farber still claims for a ‘craftsman’ to the termite art. A creator that works with his hands and who is deeply attached to his trade, to the point that is his pulse and his time, what finally remains engraved in the craftwork: ‘The best examples of termite art appear in places other than films, where the spotlight of the is nowhere in evidence, so that the craftsman can be orenery, wasteful, stubbornly self-involved, doing go-for-broke art and not caring what comes of it’ (FARBER, 2009: 535). It is Perlov shooting form the window of her daughter’s living room in Paris, recording the courtyard where a girl plays with her doll. A shot from above that captures it all: the courtyard, the entrance door and the girl. Then, still from above, a shot that takes only the girl playing with her doll. ‘For me a diagonal move often succeeds’, he comments. He starts to make diagonal moves between the girl, and what he captures of the door with that same focal length (only a small strip of the street), the arrival of the camera to the door gets to capture a passer-by. He goes back to the girl to repeat that same movement. Again, the camera captures another walker: ‘Lucky again’. Immediately afterwards, a vertical movement between the girl, and the ceilings of the building, he concludes: ‘Straight lines have never lead to anything’ (Diary, 1973-83).

On the opening sequence of The Long Holiday (De grote Vakantie, 2000),Johan Van der Keuken comments that the movie will be a dialogue between film and video formats. Inside a car, at sunset, the filmmaker confesses that his health condition will determine the format of the film. When his body allows him to, he will keep shooting on film, and when he will be no longer capable, he will be obliged to capture the images in video, a much more light and portable media. Already in 1982, in an article about Vers le Sud (1981), Serge Daney had noticed the corporeity that emerged form Van der Keuken’s films6: ‘Great cameramen know better than anyone how to involve others in the matters of film. (…) they often invent obstacles, play rules. I like that for Van der Keuken the moral passes through the physical fatigue. It is a matter of the gap between the time of the word and the time of the image. It takes time to speak, to look doesn’t’ (DANEY, 2006: 135).

In this sense the filmmaker-craftsman, demands a technical knowledge, a capacity to manipulate himself the tool he uses to capture his images. Is the quest of Perlov: ‘May 1973. I buy a camera. I want to satart filming by myself and for myself. Professional cinema does not longer attract me’. (Diary, 1973-83). The one of Rouch when he inserts to his camera a rear-view mirror that lets him react even to the image behind him. It is how Van der Keuken has forever approached filmmaking, as the cameramen of his movies. But it is also the possibility of synchronic sound, of being able to carry the camera on the shoulder, on the body, in the hands. It is the relationship between the filmmaker and his tool: ‘It will be then, the specificity of media what determines the paths to follow to partially unknown goals’ (VAN DER KEUKEN, 1995: 20).

What this domain of the technique implies is the possibility to engrave the body of the filmmaker in the image he is creating. The image, not as a double or a reflection of the world, but rather as a reflex of the body through the camera, through the technique, through the image7; similar to what Farber found on the actors. In The Long Holiday (2000), after a black screen in which the filmmaker relates death with the impossibility to be able to see an image again, the screen fades in, to the middle of a road. The balancing images of the dry soil are seen through the tired rhythm of the camera operator. The incorporated microphone of the camera, records what is in the counter-filed: The filmmaker’s breath. Almost at the end of the shot, barely the feet are seen through the edges. A very intimate relationship between the filmmaker and the camera is settled here, and finally it is through it that the condition and the sensation of the body are perceived.

The possibility to inscribe the body of the filmmaker in the image by unveiling his technique, also intends to record the traces of the creation experience and the image potentials. It is, as well, about bringing closer the shooting and the editing moment, exactly as Perlov mentions: ‘My editing is such that in the final product I want also to discover the “seams”, the raw material, the craft: the shots, their lengths, their angles’ (PERLOV: 1996, 3). It is what Pasolini does in Africa, capturing the possible faces of his characters, identifying their gestures. It is Perlov in the last episode of Diary, looking for the face of a woman he recalls from his childhood between the anonymous walkers. ‘She must have been younger, she certainly never wore a hat. But Doña Guiomar had the same piercing glance’ (Diary, 1973-1983), he comments over the face of a woman that looks deep into the camera. It is, once again, to test versions of the image through the image itself, to discover what is specific to the medium by testing its own limits. To appeal to some kind of camera-crayon that allows to sketch, as if it was a drawing, with cinema. Change intensity with the pulse, erase, repeat.

ENDNOTES

1 / Farber writes in the article: ‘Elmer Rice seems to think that art is incapable of happening when tow or more people take part in its creation (…) In Young Mr. Lincoln there is an equal grasp of the idea in the direction of John Ford and the acting of Henry Fonda. The same unity occurs in Alexander Nevsky with Prokofieff’s music, Tisse’s photography and Eisenstein conception. Nor car one discern who is more responsible fore “The passion of Jeanne d’Arc cameraman Rudolph Maté or director Carl Dreyer.’

2 / See Servitudes de l’enregistrement sonore. Entretien avec Jean Rouch par Eric Rohmer et Louis Marcorelles. Cahiers du cinema, no.144, June 1963, pp 1-22.

3 / He wrote in The Trouble With Movies, 1943 ‘It is the use of the literary writer’s technique of storytelling (rather than a technique developed specially to movies) which results in scripts that miss the essential fact that the camera medium is enormously fluid: having a voice, eyes and legs, it is more fluid than any other medium’(FARBER, 2009: 67).

4 / About Lifeboat y Casablanca in Theatrical Movies, article published in 1944, he wrote: ‘It is my opinión that the fascination of these two films lies in a visual fact, that of a watching vital invigorating-looking peopel, but no anything they are doing or saying’ (FARBER, 2009: 145).

5 / ‘The movie that disrupts and designs events to make a play of them before the camera immediately destroy the felicity of the camera: there is no event left, only representations of it, and the preservation of the purity of the event is the reason for being of the camera’ (FARBER, 2009: 144).

6 / Daney quotes Van der Keuken: ‘Having to carry the camera on keeps me fit. I have to matain a good physical rythm. The camera is heavy, at least it is for me. It weights 11 kilograms, with a battery of 4 and a half. A total of 16 kilograms. It is a weight that counts, and that makes the movements of the machine imposible to take place for no reason. Each move counts, is compelling’ (DANEY, 2004: 135).

7 / Johan van der Keuken comments: ‘The arrival of Rouch films, Les Maîtres-Fous, and above all, Moi, un Noir, represented another blow. Suddenly, the idea of a “cinematographic sintaxis” wich already was arousing infinite doubts to me, resulted in a “body sintaxis” that dictated the continuity of the images and the sounds’ (VAN DER KEUKEN, 1995: 17).

ABSTRACT

Based on some statements of Manny Farber about the actors, the storytelling, the industrial cinematographic production, and especially his reflections on the Termite Art concept, this paper studies the necessity of the contemporary filmmaker to appropriate the technological paraphernalia of industrial filmmaking, to favour a free and intimate creation with cinema medium. Thus, through Diaries (1973-1983) by David Perlov and De Grote Vakantie (2000) by Johan van der Keuken, the figure of the filmmaker-artisan, and the notion of film essay are questioned, approaching as well, the particular relation between the filmmaker and the camera.

KEYWORDS

Limit, matter, body, cinematographic technique, record, montage, test, draft, filmmaker-artisan, Termite Art.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

DANEY, Serge (2004). Cine, arte del presente. Buenos Aires. Santiago Arcos Editor.

FARBER, Manny (1971). Arte Termita contra Arte Elefante Blanco y otros escritos sobre cine. Barcelona. Anagrama.

FARBER, Manny (2009). Farber on Film. The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber. POLITO, Robert (Ed.). New York. The Library of America.

PERLOV, David. “My Diaries” (1996) The Medium in 20th Century Arts. (http://www.davidperlov.com/text/My_Diaries.pdf)

VAN DER KEUKEN, Johan (1995). Meandres. Trafic nº 13, Paris, 1995, pp 14-24. (http://leyendocine.blogspot.com.es/2007/05/meandros-por-johan-van-der-keuken.html)

CAROLINA SOURDIS

B.A in filmmaking by Colombian National University, M.A. in Film Studies and currently a PhD researcher in the Department of Communication at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona. She is member of the ‘Latin-American Observatory of Film History and Theory’, a Colombian-based research group. She won the Colombian Culture Ministry National Scholarship on film and audiovisual investigation in 2010. Her investigations have primarily approached montage and film archives in Colombian documentary, as well as film-essay in European Cinema.

Nº 4 MANNY FARBER: SYSTEMS OF MOVEMENT

Editorial

Gonzalo de Lucas

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEW

The Law of the Frame

Jean-Pierre Gorin & Kent Jones

DOCUMENTS. 4 ARTICLES BY FARBER

The Gimp

Manny Farber

Ozu's Films

Manny Farber

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Manny Farber & Patricia Patterson

Nearer My Agee to Thee (1965)

Manny Farber

DOCUMENTS. INTRODUCTIONS TO MANNY FARBER

Introduction to 'White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art and Other Writings on Film'

José Luis Guarner

Termite Makes Right. The Subterranean Criticism of Manny Farber

Jim Hoberman

Preface to 'Negative Space'

Robert Walsh

Other Roads, Other Tracks

Robert Polito

The Filmic Space According to Farber

Patrice Rollet

ARTICLES

Hybrid: Our Lives Together

Robert Walsh

The Dramaturgy of Presence

Albert Serra

The Kind Liar. Some Issues Around Film Criticism Based on the Case Farber/Agee/Schefer

Murielle Joudet

The Termites of Farber: The Image on the Limits of the Craft

Carolina Sourdis

Popcorn and Godard: The Film Criticism of Manny Farber

Andrew Dickos

REVIEW

Coral Cruz. Imágenes narradas. Cómo hacer visible lo invisible en un guión de cine.

Clara Roquet