SHARING THE GESTURES OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Alain Bergala

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ASBTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / BIBLIOGRAPHY AUTHOR / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ASBTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / BIBLIOGRAPHY AUTHOR / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Statements compiled by Núria Aidelman

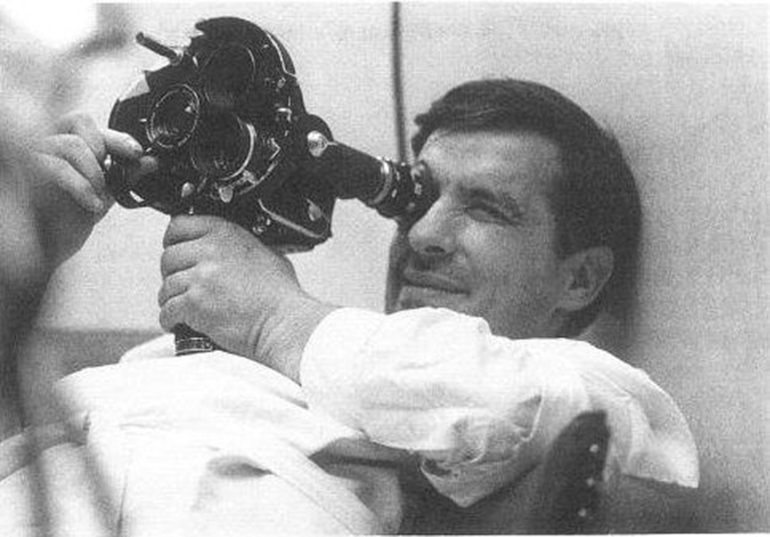

Bottom: John Cassavetes

Transmitting the Creative Process

If we are to transmit cinematographic issues to students then we must get to the heart of those issues. If we do not formulate our questions from the point of view of the creative work, then we perform a task that is formal, partial and insignificant. To speak of how the shot scales are used is not worthwhile or at all useful, even if it is comforting. On the other hand, to approach cinema by positioning oneself at the heart of the cinematic process requires bold teachers who are disposed to do this and who are not afraid. We must encourage them and enable them to reach an understanding of certain issues through their own experience. That may sound obvious, but in fact there are few examples of the transmission of the creative process, even in the Fine Arts.

When I gave training sessions for teachers, during the ministry of Jack Lang,1 I would give them a camera on the first day and one rule for the game. They were completely lost. I suggested an exercise that involved shooting and editing in-camera in two hours, for example. Then we watched Mekas and other films shot in that way. It came as a real shock. It didn’t help at all if I explained the pedagogical theory, but on the other hand, carrying out a practical experience, however small, changed everything. If I instructed them to go out one afternoon and record three shots, then they would learn a thousand things about the cinema. That is where we must always begin in education: by proposing to teachers that they begin with creative experience.

Sharing the Gestures of the Creative Process

A film is not pure enunciation. The relationship between the filmmaker and his characters is fundamental. To demonstrate this, it is enough to choose some good examples. If we take Summer with Monika, for example (Sommaren med Monika, Ingmar Bergman, 1953) it is not difficult to see that there are scenes in which what is at play is not the relationship between the characters, but the way Bergman relates to his characters. The choice of excerpts is crucial.

But for the most part, nobody makes this clear either to the teachers or the students. Especially in France, due to our tradition, films are studied as closed objects. We tell ourselves that we are performing objective analyses. Many people get uncomfortable when I tell them that it is possible to perform an analysis of the creative process. I always cite that great Renoir quotation, which says that to love cinema you have to make it, even if it means doing it in your head, imagining the film2. Then there is Nabokov, when he tells his students that he has not spent a year teaching them literature so that they can talk about or identify with the characters; he has taught them literature so that they can share in the emotion of the author who wrote the book3.

As far as this approach goes, I do not have many followers. It irritates the academics because it casts doubt on all their certitudes, the certitudes of academic knowledge. But other types of knowledge exist, and these are accessed in other ways. There are many objective elements in a filmmaker’s thinking and creative stance: in certain shots and sequences we may analyse the choices and decisions that testify to the process, to how they have come to be filmed or edited in that way. With the sequence of the paintings in Passion (Passion, 1982) for example, that I often invoke, this is exactly what Godard does: he starts with the paintings and shows how he works with them, one after the other. In the film we have the marks of Godard’s process. We see it.

The best way to approach the cinematic work is through very good and well chosen excerpts. To linger over them, over the details and to compare them. But the academy recoils in horror from this type of contemplation, which, seen properly, is really a test of intelligence and empathy.

Instead of saying, ‘this is the sequence, and we are going to reveal the structure’, we can try to comprehend how this sequence was reached. It is a fascinating process, a constructive experience and at the same time, a source of pleasure. The deliberation, based on the analysis of the elements of the sequence, brings one’s relationship with the film to life. The viewer or analyst’s pleasure consists not only in taking on board the film, but also in empathising with the processes and choices by which the film we are watching has come into being, in perceiving the emotions of the filmmaker. Certain films that are very well made and that I can appreciate as wonderfully filmed, leave no room and instil no empathy for the process that has made them. For me, a very important part of the viewer’s pleasure derives from the potential to empathise with the filmmaker, with their doubts, fears and working process. This approach multiplies. And it has nothing to do with the delirium of interpretation, but rather involves taking as a starting point the film just as it is.

One way of performing this type of analysis consists in comparing excerpts from films in which a similar situation is presented, and noticing that the creative processes and choices are not the same. For example, if we take the pool scene in Three Times (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 2005) and the corresponding table tennis scene in Match Point (Woody Allen, 2005) we see that the creative gesture is different and there is a different way of thinking about the cinema. We learn through making this comparison. If we see only one approach, then it seems to us that this is the only way it can be done, and this makes it difficult to put ourselves in the position of the filmmaker who has travelled along a certain path to reach that point and make the film the way it is. If we compare, we see how each filmmaker has found their way of filming.

Bottom: Match Point (Woody Allen, 2005)

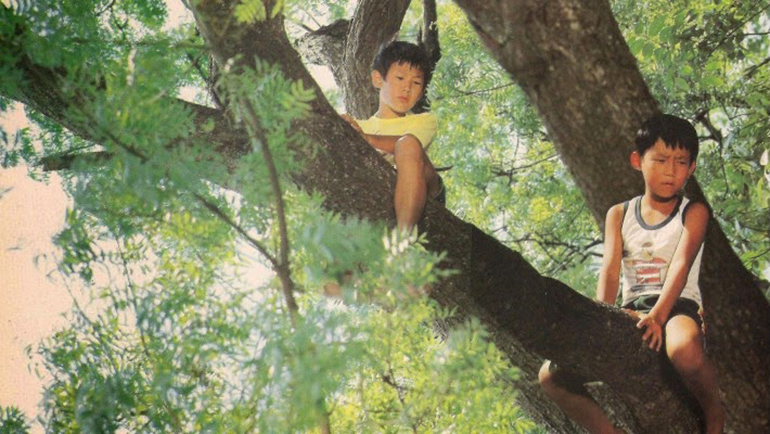

We can make comparisons between scenes that serve an equivalent function in different films by different filmmakers, or compare scenes by the same filmmaker. In the second case, we may sometimes find that there is an impulse that drives this filmmaker that is independent of the motifs and themes that he films. For example, in his first films, Hou Hsiao-Hsien is always distant, out of place or in the wrong place, with a strange point of view. After he explained to Olivier Assayas that at a young age he would look at the world from up a tree, that he was far removed, then we understood it, we grasp why he makes films in this way. One statement allows us to discover the origins and determine which roots of creativity are developed over the course of various films.

Sense and the Sensible [le sens et le sensible]

I do not believe it is necessary to separate the meaning of a film from how it appears to the senses. To do so would involve betraying and distorting the film, reducing it. To speak of the sense of a film, we must always begin with that which is sensible, what we see and hear. If we set up dichotomies, we kill the object. It is about being able to describe something that belongs simultaneously to the realms of sense and sensibility. We should never depart from the meaning, but nor should we establish separate categories. The greater the degree to which all categories are mixed, the richer the analysis: the meaning, the sensible and the creative gesture. It is not easy and teachers are afraid that they are not able to do it.

You Cannot Encounter Art by Breaking it Down

The only way of getting close to art is to take an artistic work or an excerpt that contains everything, with all the contradictions. I continue to believe that approaching art ought to be an encounter. And you cannot encounter art by breaking it down. That would be like visiting the Louvre and saying: today we will see only blue, or only the picture frames. We are before a painting with all that entails for the viewer and stirs within them. We should leave the speeches for later.

I have never believed, nor will I ever believe, in analytically breaking things down for the sake of learning. It is all very generalised. The lecturer arrives and says, ‘I’m going to explain the scale of shots’. But the scale of shots is not a thinking-through of the shot; it is the opposite of a thinking-through of the shot.

The idea that the cinema can be broken down is false. It is a product of fear. It has been imposed because it reassures everyone, including the institutions. To break something down in order to understand it sounds reasonable and it is comforting. But it is simply false. We do not learn anything in life this way. We learn of everything mixed together, confused and in a block. It is much more complicated but also fascinating.

Watching Cinema in a Cinema School

There exists the lazy and out-moded belief that in a cinema school ‘doing’ is sufficient. And a fundamental problem in all the schools is precisely that: that too often, the students take into account only their own ideas, their own genius, and they feel that they are sufficient in and of themselves without the need to watch films. This is my battle at La Fémis, to tell them that if they count only on their own ideas and on what they already know, they suffocate themselves and their films will be minor in status. If they count only on their own energies, they will not make good filmmakers. Little by little, this idea –I would almost say, this battle– ends up taking root, and they end up discovering that the cinema of yesterday and the different cinema of today can help them to think through their cinema.

The programme at La Fémis is so tight, the training so intense, that they have no time: they go to cinemas less than the ‘normal’ students. Because of this, we have to bring the cinema to the school. In addition to the excerpts and films convened by the filmmakers-teachers, the viewing develops by other means.

In the first place, inviting filmmakers. Recently the Dardenne brothers came and in their reflections they revealed themselves as the great filmmakers that they are. Over two days we watched excerpts from their films, we talked about how they work, so the students understand. Direct contact with a filmmaker who honestly explains his work is something precious. We try to organise two-day seminars or, when that is not possible due to the schedules of the filmmakers, short meetings of two or three hours, and it is always revealing.

I also give a course to the first and second year students. I select a theme and taking it as a starting point I work with many excerpts and a number of films in their entirety. The analyses focus on the relationships between excerpts. The comparative method remains the best way to think, to give them ideas and motivation.

This year we are working on ‘the shot’. Everyone will shoot, but it is necessary to watch films in order to arrive at a concept of the shot. I started with something very simple. I took episode 4A of Histoire(s)du cinéma (Jean-Luc Godard, 1998) about which I have a theory: in the first ten minutes there is a typology of all the shots possible. It permits the students to see and think.

We also watched either the whole of the first part of Three Times or Miss Oyu (Oyû-sama, Kenji Mizoguchi, 1951), also in its entirety. After viewing the film I carry out an in-depth study of specific excerpts and shots. This year I have discovered something that works and that I ought to have discovered a long time ago. Once the viewing is over, I leave fifteen minutes so that each person can think. After that, they have things to say.

Finally, each month we invite a filmmaker to choose a film from a list that I propose to the students; they come to present and discuss the film.

Accompanying the Creative Process

In La Fémis, we undertake comparative analysis alongside the students’ exercises. I highlight the key issues for a filmmaker, the genuine problems of the cinema, and we see how they have resolved them. It is a means of indirectly analysing films. The last session considered how to film a body getting up to dance or getting undressed. It was an exercise in mise-en-scène whose starting point was the script for a scene from Blow-Up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966). Taking the problems of cinema, we applied the comparative method. It works because they see who is thinking about the cinema and thinking cinematically.

In their own creative processes, the students at La Fémis are closely accompanied by the diverse range of film professionals. These teachers are always present at shootings in the first and second years. There is a double team, that of the students and that of the teaching film professionals. The teachers being there does not necessarily mean that they will intervene, but the students have the option of making recourse to them, with all the dangers that this brings. A professional screenwriter may run the risk of introducing conformity, or causing them to submit to the norms of script-writing, and the same occurs in all areas. In a cinema school, the ‘rules’ and what is ‘professional’ are threats. I often ask my students why their film is so flat, or why the sound is mixed is a certain way, and they respond, ‘because we want to do it right.’ There is the danger: everyone wants to ‘do it right,’ everyone wants to ‘be good’. The filmmaker may ask for an unattractive image, but the director of photography resists it. The permanent danger is academicism. Creativity is an entirely different thing.

ENDNOTES

1 / Between 2000 and 2003 Alain Bergala was cinema adviser for the ‘Five Year Plan for the Development of Art and Culture in Schools’ overseen by Jack Lang, then Minister for Culture, together with Catherine Tasca, then Minister for Education.

2 / «Pour aimer un tableau, il faut être un peintre en puissance, sinon on ne peut pas l’aimer; et en réalité, pour aimer un film, il faut être un cinéaste en puissance; il faut se dire: mais moi, j’aurais fait comme ci, j’aurais fait comme ça; il faut soi-même faire des films, peut-être seulement dans son imagination, mais il faut les faire, sinon, on n’est pas digne d’aller au cinéma» (RENOIR, 1979: 27).

3 / ‘I have tried to make of you good readers who read books not for the infantile purpose of identifying oneself with the characters, and not for the adolescent purpose of learning to live, and not for the academic purpose of indulging in generalizations. I have tried to teach you to read books for the sake of their form, their visions, their art. I have tried to teach you to feel a shiver of artistic satisfaction, to share not the emotions of the people in the book but the emotions of its author – the joys and difficulties of creation. We did not talk around books, about books; we went to the center of this or that masterpiece, to the live heart of the matter’ (NABOKOV, 1997: 542).

ABSTRACT

The article considers key issues in order to develop an analysis of creation in different formative fields. It bases the approach on empathy with the creative process of the filmmaker, the comparative viewing of excerpts, and rejection of the scholarly and academic deconstruction of films for analysis. Based on experience, the author presents some of the methodologies that he has developed for the training of teachers and as professor at La Fémis. For those teachers to transmit cinema from the heart of the cinematographic creative process, he considers it fundamental that they experience practice. In the case of the cinema school and its students, it is essential that they are able to consider cinematographic issues through the comparative viewing of a range of films, the first-hand and in-depth accounts of filmmakers and the analysis of their own practices. The author ends by outlining the risks posed by academicism in cinema schools as opposed to the experience of artistic creation.

KEYWORDS

Pedagogy, transmission, creative process, film excerpts, cinema school, comparative method, cinematographic analysis, teacher training.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

RENOIR, Jean (1979). Jean Renoir. Entretiens et propos. NARBONI, Jean (ed.). París. Cahiers du Cinéma.

NABOKOV, Vladimir (1997). Curso de literatura europea. Barcelona. Ediciones B.

ALAIN BERGALA SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

BERGALA, Alain (ed.) (1985a). Jean-Luc Godard par Jean-Luc Godard (Tome 1). París. Cahiers du cinéma.

BERGALA, Alain (1985b). Roberto Rossellini. Le cinéma révélé. París. Cahiers du cinéma.

BERGALA, Alain (1990). Voyage en Italie de Roberto Rossellini. Crisnée. Yellow Now.

BERGALA, Alain (1992). Le cinéma en jeu. Aix-en-Provence. Institut de l’Image.

BERGALA, Alain (ed.) (1998). Jean-Luc Godard par Jean-Luc Godard (Tome 2). París. Cahiers du cinéma.

BERGALA, Alain (1999). Nul mieux que Godard. París. Cahiers du cinéma. Traducción al castellano en: BERGALA, Alain (2003). Nadie como Godard. Barcelona. Paidós.

BERGALA, Alain (2002). L’hypothèse cinéma (Petit traité de transmission du cinéma à l’école et ailleurs). París. Cahiers du cinéma.

BERGALA, Alain (2004). Abbas Kiarostami. París. Cahiers du cinéma.

BERGALA, Alain (2005). Monika de Ingmar Bergman (du rapport créateur créature au cinéma). Crisnée. Yellow Now.

BERGALA, Alain (2006). Godard au travail, les années 1960. París. Cahiers du cinéma.

ALAIN BERGALA

Director of the Department of Film Studies at La Fémis and Emeritus Professor at Paris III. He was editorin-chief of Cahiers du Cinéma and he has directed films for both cinema and television. He is the author of numerous books and articles, including Roberto Rossellini: Le cinéma révéle (1984), Voyage en Italie (1990), L’hypothèse cinéma (2002) and the following books on Jean-Luc Godard: Godard par Godard (1985-1988), Nul mieux que Godard (1999) and Godard au travail (2006). Between 2000 and 2003 he was the cinema adviser for the ‘Plan for the Development of Art and Culture in Schools’ run by the Ministries of Education and Culture. He has also curated numerous exhibitions, including ‘Erice/Kiarostami Correspondances’ and ‘Pasolini Roma’.

Nº 5 PEDAGOGIES OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Editorial. Pedagogies of the Creative Process

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTOS

The Goodwill for a Meeting: That's cinema

Excerpts by Henri Langlois, Jean-Louis Commolli, Nicholas Ray

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Filmmaker-spectator, Spectator-filmmaker: José Luis Guerin's Thoughts on his Experience as a Teacher

Alain Bergala

Filmmaker-spectator, Spectator-filmmaker: José Luis Guerin's Thoughts on his Experience as a Teacher

Carolina Sourdis

ARTICLES

In Praise of Love. Cinema en Curs

Núria Aidelman, Laia Colell

A Daring Hypothesis

Jonás Trueba

To Shoot through Emotion, to Show Thought processes. The Montage of Film Fragments in the Creative Process

Gonzalo de Lucas

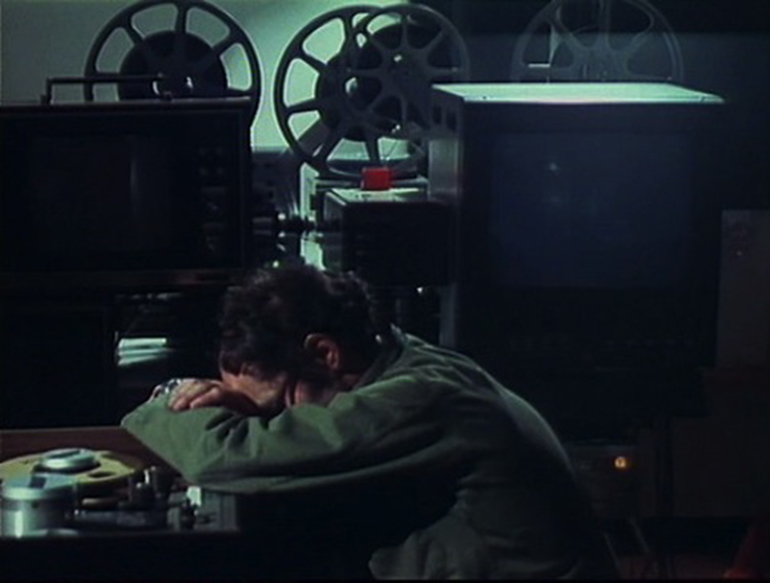

The Transmission of the Secret. Mikhail Romm in the VGIK

Carlos Muguiro

The Biopolitical Militancy of Joaquín Jordá

Carles Guerra

REVIEWS

AA,VV. BENAVENTE, Fran y SALVADÓ, Glòria (ed.), Poéticas del gesto en el cine europeo contemporáneo.

Marga Carnicé Mur