THE TRANSMISSION OF THE SECRET. MIKHAIL ROMM IN THE VGIK

Carlos Muguiro

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

The VGIK1 survives today as the oldest filmmaking training centre of the world, almost 100 years after its opening. Nevertheless, it was not the first film school of post-revolutionary Russia. Early in 1918, the Education Commission (Narkompros), directed by Anatoli Lunacharski, strategically decided to activate dozens of new pedagogical experiments sustained in the practice and the resolution of concrete and quotidian problems. Urged by the need to assign loyal and committed specialists heading the modernization and socialization plans of the country, they required to complete the professional staff in diverse areas such as engineering, finances, administration and cinema; naturally, in cinema as well, due to, among others reasons, the professional vacuum generated by the exile of some of the most distinguished technicians and directors.

The project was first developed with local centres, such as the School of Screen Arts in Petrograd (SEI) and the Odessa State College of Cinematography. Later, in 1919, it continued through the foundation of the State College of Cinematography (GTK), as the VGIK was formerly named. Narkompros commissioned the design of the curriculum to the veteran filmmaker Vladímir Gardin. The veteran director imagined down to the last detail, a four year itinerary based on practical workshops guided by a mentor, inspired by the ‘work and learn simultaneously’ slogan, and the line of ‘learning-by-doing’, proclaimed by Lunacharsky as general guideline to Soviet film education (KEPLEY, 1987: 5-7). The first course started in autumn 1919 with 25 students.

This fundamentally teknikum and non-artistic approach, helps to explain the two hypotheses of film education, assumed as obvious today, over which the first film school was founded upon. The first one, presupposed that following a more or less regulated and methodical pedagogy, was as well possible to create filmmakers, like engineers or topographers. The second one, presumed that, who could better provide this technical training were the filmmakers2 themselves, precisely because it was intended to create filmmakers, as engineers and topographers3.

Undoubtedly, there are many VGIK in the hundred years of the VGIK; however the decision to make the filmmakers –the great masters– the ones who comprised cyclically the teacher staff, granted to the institution, from its early beginnings, the power to construct the Soviet cinematography as tradition, this is to say, as a great intergenerational tale of custody and transmission of the secret. The famous secret the master whispers to his apprentice in his deathbed for art not to be ruined or distorted4. Without an exhaustively intent, the object of this paper is to describe a concrete episode of the paradigm of the school as narrator of the Soviet cinematographic tradition based on the figure of Mikhail Romm, his direction workshop held in the fifties and sixties, and the disconcerting and cyclonic encounter with his students.

2.

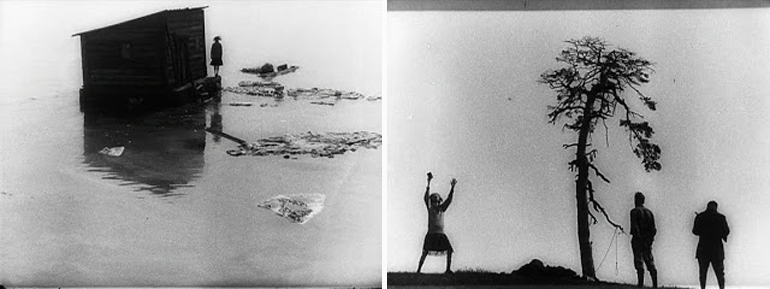

During 1963, Mikhail Romm started the overly postponed and monumental process of reviewing the never-ending footage confiscated from the Reichfilmarchiv by the Red Army. In large sacks in Mosfilm since 1945, among other materials, the Deutshche Wochenschaui, kultur-films, the Goebbles funds, and collections of images from Hitler’s personal photographer, Heinrich Hoffman, besides others from the SS that had operated in Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Belarus, had been kept in custody. «We watched around two million and a half metres of film, which is more than half of what was preserved: we stopped there, we couldn’t go any further» (HAUDIQUET, 1966). Romm started to organize the material according to 120 possible topics, and later combined the images based on 16 chapters that would finally structure his movie Ordinary Fascism5 (Obyknovennii fashizm, 1965) (ROMM, 1965: 4). Through decontextualization, hyperbole and contrast achieved by montage, those historical documents began to acquire an intriguing ironic twofoldness; and purely by friction (not fiction6), they started to dismantle the processes of construction of the public discourse from power, the Soviet power7, by extension.

Following the standardized guidelines of compilation documentary, Mosfilm suggested the text to be read by a neutral and disembodied voice: either Iurii Levitán, the official radio announcer, the actor Innokentii Smoktunovskii, or the German actor and singer Erns Busch (TUROVSKAJA, 2003: 198). However, throughout the previous months, Romm had imagined the possibility of incorporating himself to Ordinary Fascism, a movie he had always considered, not at all capriciously, a personal legacy to younger people who had not known the war. Encouraged by his closest collaborators, Romm finally decided to make himself present in the film as voice transmuted to filmic matter; transposing to the film, the testimonial courage he had practiced for over a decade in the classrooms of the VGIK.

Not he only assumed to put his thoroughly human voice to the film, or address the spectator in first person –both consequences of a radical heterodoxy in Soviet film–, but he permitted his reflections to flourish, in certain way spontaneously, facing the projection of the film: like if he was improvising a class with his students or having a conversation with the spectator. After all, the intention was not to project the voice as images are projected, with that same clarity and that emphatic luminosity of a powerful spotlight; rather it was to incorporate to the images that dubitative and intermittent quality in search of the exact word that characterizes the process of thought itself. Romm explained:

We assembled the work as a silent film. I improvised the comments section by section, without thinking of synchronization, or pursuing standardized ‘documentary’ effects. It was like a monologue where I was verbalizing the ideas that came to my mind as I watched the material. And at the same time, I was claiming for the attention of the spectator, so they would think, as well, about what they had in front (ROMM, 1975: 279).

Based on the usages of voice Gonzalo de Lucas details, it can be concluded that through these choices, Romm articulated the voice as ars poetica8; because it moved between the aesthetic treatise and the critical revision of history, art and cinema, all three undifferentiated in a whole cinematographic body (DE LUCAS, 2013: 54).

The first person singular had never before acquire such importance in Soviet cinema, not only because of the malleability of the voice, but also because of the organic dimension of the spoken word, being both voice and breath of the already sexagenarian and tired Romm. Facing the screen, he doubts, whispers, searches for the word from an undetermined somewhere, yet earthly. Romm is so close to the spectator that they can even guess the mouthfuls of smoke that calmly, were accompanying each one of his phrases. Furthermore, the self of Romm, gains a disconcerting metaphorical power through the film, especially in chapter VIII entitled ‘About myself’. Specifically dedicated to the cult of personality around the Führer, in this chapter Romm speaks as if he was Hitler himself, in first person. The Faustic effect that this feature generates with the appropriation of the body of Satan himself, making Hitler say platitudes to portrait him in his patheticism, not only produces a disconcerting and liberating effect for the observers of such demonic ritual, but also makes the spectator notice the ancestrally magical power of voice, capable of possessing any image and bewitching it until the loss of its will. Regarding this point, Romm’s voice, even makes reference to Russian literary tradition of demonic farce cultivated by such authors as Andreiev, Bielei or Bulgakov, who already suspected about the schizophrenic division of subjectivity, about the selves of the self.

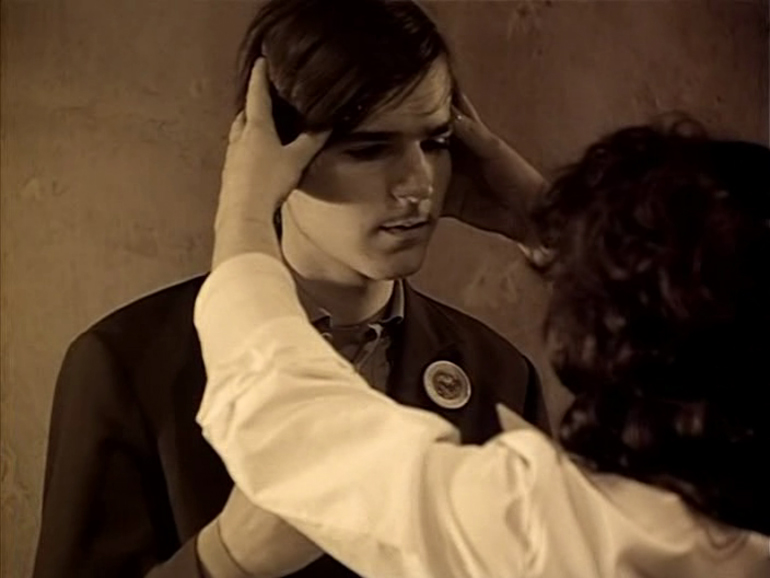

The emergence of the voice –the voice itself, the voice of the absolute self– accomplished by Ordinary Fascism supposes a turning point in the rotational axis of Russian cinema, though its effect can only be fully appreciated at distance9. Ten years after this film, Romm’s beloved disciple Andréi Tarkovski, included at the beginning of The mirror (Zerkalo, 1975) a sequence that indicated, by way of a buoy, the deepness of the waters from which it emerged: an equally hybrid and original film about the articulation of the most extreme subjectivity. In that first scene, a young man with a speech dysfunction undergoes the healing of his stammering by hypnosis. ‘I will remove the tension now, and you will speak clearly and effortlessly– he is told–. You will speak loudly and clearly for all your life. Look at me. I will remove the tension from your hands and your speech. One, two, three. Say: ‘I can speak’’. Even ten years after Ordinary Fascism, to conjugate a film from the subjectivity of the author that can not be shared (I CAN SPEAK), meant such a sin of the bourgeoisie and formalist egomania that Tarkovski ended up condemned to exile.

The articulation of the filmmaker’s subjectivity in Soviet cinema was a long and interrupted process that correlates the works of Romm and Tarkovski, and simultaneously takes us to the preceding time, the begging of the Thaw, when Mikhail Romm started to impart his direction workshop at VGIK. Something happened in those classrooms, between introspective therapy and magical ritual, as staged in Tarkovski’s film, which transformed the ‘I CAN TALK’ into a collective and generational need. Now it is time to go to its classes.

3.

In autumn 1955, One year after the 20th Congress of the CPSU where the critic to Stalin and the beginning of the Thaw were officialised, Mikhail Romm accepted the entry of Andrei Tarkovski to the VGIK, against the opinion of the rest of the examiners. Tarkosvki was incorporated to his workshop, together with Vasilli Shukshin, Alexánder Mittá and Iulii Fait. During the four years of the Degree, Romm protected under his authority this first generation of filmmakers of the Thaw, who were called to transform cinema in the Union. ‘He has an interesting group –Serguéi Soloviov recalled the words of the Ministry of Culture–, although there are two people that obliterate the class: the schizophrenic named Tarkovski, and that imbecilic named Shukshin, who came from somewhere in Altai’. Some years later, Tarkovski would compare master Romm to a King who governed without exerting power or imposing his opinion, even without teaching the craft, because Romm’s invitation was rather to journey through one’s own darkness and to identify one’s individual singularity (GIANVITO, 2006: 66).

In the thirties, through movies such as Lenin in October (Lenin v oktiabre, 1937) and Lenin in 1918 (Lenin v 1918 godu, 1939), Romm had contributed to construct the idea of Lenin as an idealized embodiment of Soviet justice. This icon of the leader, risen up with certain innocence, was rescued and incorporated to the political discourse Nikita Kruschev pretended to restore in the late fifties, following the idea that the critics to Stalinism simultaneously led to the mandatory restoration of the foundational myth.

This rare braid through which ‘cinema had created an image that had transmuted to reality’ (EISENSCHITZ, 2000: 142), as explained by Naum Kleiman, undoubtedly provoked in Romm an intense disconcert regarding his responsibility as a filmmaker in the construction of the past. For a figure like Romm the new time was time for reflection. ‘Those who knew and know the director –Pogozheva wrote– at least could realize the internal change he was going through in the course of this period’ (POGOZHEVA, 1962). In addition, a great intergenerational change was taking place in Soviet Cinema in these years. Once again, the veteran filmmaker was placed against the contradictions between the individual memory and the historical record10. According to Kleiman, who attended the school in 1956, ‘Romm plunged into crisis. He assumed Khrushchev’s discourse very painfully. He did not work for two years in order to understand what was going on. Thus he devoted to carpentry, and later he decided to help young people’, some others came after him, ‘but Romm took the first step’ (EISENSCHITZ, 2000: 142). It was in this particular state of reflection where the classrooms of the VGIK were transformed into scenery for the talking cure.

Romm discovers almost at the same time his hands as a carpenter and his voice as a master. It was usual to see him with a little dictation machine he carried everywhere during these years, as Klímov would later remember. (MUGUIRO, 2005: 46). He kept recording indistinctly some unimportant notes and merciless confessions. Romm confesses to himself: ‘Can one leave behind one’s customs, detach from the skin of one’s habits, remake oneself, be reborn? In the midst of this torrent of doubts I decided to settle some of the points of my path to come. I made some promises, I even pronounced them loudly one night’ (ROMM, 1989: 82-83). Concurrently in the classrooms of the VGIK, as an extension of this time of reflection, Romm continued to formulate questions, analyse his work, open himself to the critic, and incite contradiction. As his students would later remember, Romm did not teach anything apart from himself. Soloviov summarizes it: ‘he must had been gifted with a truly greatness of spirit in order to stay there, in front of us, his students, giving explanations of his work on cinema’ (MUGUIRO, 2005: 47). Therefore, the experience of the voice was not merely a conceptual exercise, restraint to the articulation of discourse, but rather, a form of personal embodiment radically physical. As opposed to the written word, for Romm, the voice included the possibility to mute, to inhale the smoke of the cigarette, to take a breath, a sigh. ‘To breath is to create a whole in the attention that could be unfolded’ (PARDO, 2002), reminds us Carmen Pardo. To go through those long silences was a form of self-alteration for the young apprentices.

Evgenii Margolit has explained that in the history of VGIK, as long as it took place, the exchange of experience and the dialogue between generations, provoked such extraordinary results as the encouragement of ‘the artists to go deep beyond the canonical prescriptions and succeed over them’ (MARGOLIT, 2012: 371). Something similar happened in Romm’s workshop, producing an unusual fruitfulness in the history of the centre. Anyway, also according to Margolit, Romm’s diagonal style had important precedents inside the institution, particularly in the unforgettable sessions by Igor Sávchenko, professor at VGIK between 1945 and 1950. Although Romm did not attended to his classes, in this classroom as well, the dialogue between peers became the essence of the relation between master and disciples. ‘When we analysed something we had done –Danilov said–, something we had written, or something we had shot, he talked ceaselessly. Consciously or not, the work of Sávchenko with his students turned out to be a powerful way to confront the famine atmosphere of cinema and the absolute un-individualization of the students. It was a way to incite the consolidation of their singular points of view’ (DANÍLOV, 2012: 371).

However, Romm’s workshop was not a purely inductive system, rather it also implied disconcert and contradiction in the most orthodox sense of dialectical collision and synthesis. ‘I considered you as serious people, authentic creators with their own personality –Savva Kulish reconstructed the exasperation of the master when they showed him some corrections they had made to their movie The last letters (Posledniye pisma, 1965), according to the suggestions of the master himself–, why the hell you obey so blindly? What If I have misunderstood? Or if I am wrong?’ (MUGUIRO, 2005: 44). This much more irascible and strategic version of the master, far from the spontaneity of Sávchenko, brought Romm closer to Eisenstein.

4.

To address the pedagogical system designed by Eisenstein exceeds the purposes of this paper, but it is convenient to briefly point out that, particularly between 1932 and 1935, Eisenstein tried to develop at VGIK his revolutionary ideas about film education with almost no political interference or administrative supervision (MILLER, 2007: 479). The student, with sometimes disconcerting cultural and artistic references, through certain Socratic guidance and the always limited interference of Eisenstein, should begin to unravel the idea or nuclear image (the obraz image) hidden in a determined representation (the izobrahenie image) whether literary, pictorial or theatrical, that nourished it from this background: like a hidden chord from which, mysteriously, a symphony could grow. To find or synthetize that nuclear image was the purpose of exercises such as filming the murder scene of Crime and Punishment in one single shot, or editing Leonardo Da Vinci’s The Last Supper, until finding the piece that contained, concentrated, the idea of the whole painting. Vance Kepley Jr. summarizes:

According to Eisenstein, an author conceives a nuclear image (obraz) and later elaborates it through the act of representation (izobrazhenie). As opposed to the process of the author, who starts to create from the nuclear idea and works the representation formally, the spectator contemplates the finished work through the text as a representation until recognizing the central image (…) Eisenstein created [the session] as a ritual, provoking the students a reaction towards the master works of art he took to class. Students, as film spectators, should participate in the construction of the sense of the text, identifying the nuclear image (KEPLEY, 1993: 10).

The director and the spectator went through the same relation of dependence and necessity as the teacher and his students. In the matter of fact, Eisenstein did not find any differences between what happened in the classroom and what happened in a projection room. The circuit of sense that was activated in both audiences was indeed a psychological laboratory, equivalent and interchangeable. Therefore, Eisenstein could formulate in class, like in a test range, experiments of some of the nuclear concepts of his thought, such as the correlation between the predictable response of a subject and expressivity, an aesthetical concept that was originally taken from Russian reflexology on which he relied in his early writings (KEPLEY, 1993: 4). Controverting Shaw’s famous aphorism ‘Those who can, do; those who don’t teach’, Eisenstein founded a pedagogical system based on the certainty that teaching was a form of creation as well, not very different from that of filming (KEPLEY, 1993: 14). Giving a class like one would make a movie.

Some years later, as we have seen, Romm went one step further than his admired Eisenstein, when sizing up the inverse procedure, this is to say, the creation of a film that emanated from his voice: to make a film as he would give a class. He locked himself inside Mosfilm in order to watch dozens of reels of Nazi propaganda. He assumed his absolute role of spectator (even of what he did not want to see). Only at the end, in the same emotional place as that of the spectator, he began to speak. This was how he assumed Ordinary Fascism: ‘my voice should seem like a conversation destined to provoke reflection. It should give the impression that I am standing next to the spectator, and I tell him: Behold what fascism is, behold my own thought’ (HAUDIQUET, 1966).

Alexánder Mittá, Elem Klímov and Vladímir Basov attended Romm’s workshop; Serguéi Paradzhanov, Marlén Khutsíev and Vladímir Naumov that of Sávchenko; Grigorii Alexandrov, Iván Piriev and Vladímir Vengerov attended Einsestein’s; Stanislav Rostotskii and Eldar Riazanov, Kozintsev’s; Teguiz Abuladze and Grigorii Chukhái, Serguéi Iutkevitch’s … A never ending chain of tradition. However, not only the reverential and dazzled encounter of the students with the master took place at VGIK, but also the disconcerting and stunned encounter of the master with the students: Sávchenko’s, Eisenstein’s and Romm’s career, as that of many other eminent filmmakers, was irreversibly crossed by the presence of these so called apprentices, of whom Khutsíev, Venguerov y Klímov are only an example. VGIK did not produce series of Romms, Einsesteiins or Sávchenkos, it rather returned to Romm, Eisenstein and Sávchenko the reflections of their own needs, exterior fears and obsessions. Far from producing doubles, the institute, confronted those great masters with the enigmatic silhouette of their own shadow.

5.

The history of the VGIK as a paradigm of the great film schools can be read twofold. First, the chronological discourse sheds lights on the chain of transmission of knowledge that from one generation to another, for almost one hundred years of existence, constructed a certain cinematographic tradition in which all its protagonists have their necessary place. Second, when assembled against the grain, the history of the VGIK is not the history of the graduates, but the history of the great masters of Soviet cinematography, sheltered in the classroom for sometimes political or economical reasons, frequently confronted to their own talent and exposed against the unappealable look of a generation in search of explanations. Margolit has coined the concept of diagonal pedagogy to identify this form of horizontal relationship, which also explains VGIK’s prestige (MARGOLIT, 2012: 371).

Lev Kulechov, for example, transposed to his classes in the mid twenties, the sense of adventure and discovery nailed down in his famous experiments of montage over the face of the actor Mozzhukhin or the creative geography. He incorporated his students to the artistic and technical crew of his movies, as in The Death Ray (Luch Smetri, 1925) and By the Law (Po Zakonu, 1926) (KEPLEY, 1987: 14); From 1936 to 1938 in his laboratory, Dovzhenko delved along with his students into the adaptation of Tarás Bulba, a project that was not only seen as an act of national reaffirmation in Ukraine, but which also had serious consequences for the students, who were hardly reprised during the Great Terror (MARGOLIT, 2012: 371). For Eisenstein, the school was an intellectual and artistic shelter in one of the most tragic periods of his life, when he faced the hostility of the regime and the public and gremial censure, and found a great difficulty to begin new projects after his return from North America. Like Vance Kepley has stated, it would be impossible to understand Einsestein’s evolution through the thirties and forties, particularly his organicist aesthetics and the associative montage, without understanding his role at the VGIK (KEPLEY, 1993: 2).

6.

In 1935 Eisenstein took his students to the shooting of Bezhin Meadow (Bezhin Lug, 1937). He proposed them to get involved in the staging, dialogues and montage of the film, to later compare their results. In 1948, Sávchenko and his students boarded the shooting of the artistic documentary The Third Blow (Tetrii udar,1948), a project without precedents which required to substitute the whole course for eight months of outdoors shooting. Each of them received between 50 and 60 metres of movie, a camera and a topic. Some of those miniatures were included in the final montage of the film.

Romm died in 1971 with no time to finish his upcoming movie. There were some notes and comments registered in his dictation machine that Elem Klímov and Marlen Khutsìev used to finish the film. They shaped it as a new personal essay in which Romm went across a century as old as him through his septuagenarian memory. Vasili Aksionov had written in one of his novels that history represents a chain of small apocalypses, until the final one. That was too, the diagnosis that seemed to emanate from the finished movie. It was logical, within the context of the artistic circularity we have described, that the movie was finished by those who had discussed with him so regularly, in the school and out of it. However, Klímov and Khutsíev decided to incorporate to the film the reflexive and disconcerting personality they associated to his master. To entitle the movie, they rescued a brief text found in his desk that even controverted the general effect of the montage: And Still I Believe (I vse-taki ia veriu…, 1974). The title remained like that. It was the last breakage of dialectics. It is a paradox that echoes in the mind of the spectator, in first person with no possibility of reply. Similar to one of those long and disconcerting silences, where Romm came to question everything that had been said until then.

Translated from the Spanish by Carolina Sourdis

ENDNOTES

1 / In 1934 already under Soiuzhino’s control, the Central Cinematographic administration, held by Boris Shumiatskii, adopted that name. The letters VGIK stand for Russian denomination Vsesoiuznii Gosudarstvenii Institut Kinematografii (All-Union State Institute of Cinematography). In 1939 the centre accomplished the VUZ category (higher educational institute). In 2008 the Institute became the Panrusa Guarasimov University of Cinematography.

2 / It was not until 1934 that a non-filmmaker, Nikolái Lobedev, was in charge of the Institution. Exactly in the time the centre changed its status from Vocational School to Superior Institute.

3 / The words of Antón Makarenko, one of the foundational figures of the new post-revolutionary Russian pedagogy, must be recalled in this point. He said that the purpose of the Soviet educational system was rather to provoke the socialization of the individual than to create artists (1955:40).

4 / Let us remember the episode of Andréi Rublev, where the Young Boriska, in a desperate moment, affirms having received from his father, Nikolka, the secret of the construction of the bells; episode he would later recognize as unreal. The secret of creation seems to cross from one generation to another more as a gift than as knowledge.

5 / Romm developed the screenplay with the critics Maia Turovskaia and Yuri Khaniutin (BILENHOFF & HÄNSEN, 2008: 142).

6 / Romm expressively rejected the inclusion of fiction footage. Confronting the faces of the documentary reels, he would say: ‘Drama seems ridiculous to me. I simply can’t take it seriously’ (ROMM, 1981: 301).

7 / ‘As most of my friends, I perfectly understood that the hidden design of the director was to prove the terrible, unconditional and harrowing connection between the two regimes’ (cit. WOLL, 2008: 229).

8 / Although De Lucas’s analysis is based on works by Mekas, Godard, Cocteau, Van der Keuken and Rouch, many of his conclusions about the ‘usages of the voice’ could by applied to Ordinary Fascism. It is difficult to determine until what point Romm actually knew the essayist forms that were being explored by such authors. Whatsoever, we know about the polemic encounter he had with Godard, from which Romm concluded: ‘Western artists, writers, and filmmakers are going through a deep spiritual crisis: some of them are looking a way out from the ideological mire; the others are taking very strange alleys. I noticed that in my interview with filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard’ (ROMM, 1972: 11).

9 / For a detailed analysis of the articulation of voice in Ordinary Fascism refer to BEILENHOFF & HÄNSEN (2008).

10 / It must be taken into account that from 1955-56 to the end of the decade, almost simultaneously and in great influx, up to four different generations of filmmakers attended the VGIK and in general, were part of the industry. Although they were barely separated by two or three years in age, each generation treasured experiences and demands impossible to be shared (EISENSCHITZ, 2000: 140).

ABSTRACT

This paper describes a particular episode of the VGIK school –the oldest filmmakers training centre of the world– to study the soviet cinematographic tradition based on the figure of Mikhail Romm, his direction workshop held in the fifties and sixties, and the disconcerting and cyclonic encounter with his students. Furthermore, the long and interrupted process that implied the articulation of the subjectivity of the filmmaker in Soviet cinema, and which connects the work of Romm with that of Tarkovski, is outlined here through the analysis of the montage of Ordinary Fascism (Obyknovennii fashizm, 1965), where Romm inscribes his reflexive voice in first person. Finally, the history of the VGIK is read both as a chain of transmission and tradition between generations of filmmakers, and a place to confront the political and personal positions great filmmakers such as Einsestein, assumed when they were mentors at the Institution.

KEYWORDS

VGI, self’s voice, filmmaker’s subjectivity, Mikhail Romm, pedagogical system, transmission, diagonal pedagogy, Andréi Tarkovski, Eisenstein, nuclear image.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BEILENHOFF, Wolfgang y HÄNSGEN, Sabine (2014). Speaking about images: the voice of the autor in Ordinary Fascism. Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema, 2:2, pp. 141-153.

BOWN, James (1965). Soviet Education. Anton Makarenko and the Years of Experiment. Milwaukee/ Madison. University of Wisconsin Press.

CHUKHRAI, Grigorii (1971). Mikhail Romm cumple 70 años. Hablemos del maestro. Films Soviéticos, 1, p. 29.

DE LUCAS, Gonzalo (2013). Ars poetica. La voz del cineasta. Cinema Comparat/ive Cinema, Vol. 1, No 3, pp. 49-59.

DOBASHENKO, S. y SADCHIKOV, I. (1992). The Main Tendencies of the Film Education System in Perestroika. Journal of Film and Video, 44: 1/2, pp. 91-96.

GIANVITO, John (ed.) (2006). Andrei Tarkovsky: Interviews. Jackson (MS). University Press of Mississippi.

KEPLEY, Vance Jr. (1987). Building a National Cinema: Soviet Film Education, 1918-1934. Wide Angle, 9:3, pp. 4-20.

KEPLEY, Vance Jr. (1993). Eisenstein as Pedagogue. Quaterly Review of Film and Video, 14:4, pp. 1-16.

EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (2000). Une histoire personnelle. Dialogue avec Naum Klejman 2. EISENSCHITZ, Bernard (ed.), Lignes d’ombre. Une autre histoire du cinéma soviétique (1926-1968). Milano. Edizione Grabriele Mazzotta, pp. 139-148.

HAUDIQUET, Philippe (1966). Rencontre avec Mikhail Romm à Paris. Lettres Françaises, abril.

HERLINGHAUS, Hermann (1981). Stoff unserer Filme ist die Dialektik des Lebens. Film und Fernseben, 1, I-X.

MAKARENKO, Anton (1955). The Road to Life vol III. Moscow. Foreing Languages Publishing House. MARGOLIT, Evgenii (2012). A conglomeration of aggressive personalities: Savchenko’s students at the All- Union State Institute of Cinematography (1945-1950) and the cinema of the Thaw. Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema, 6:3, pp. 365-372.

MILLER, Jamie (2007). Educating Filmmakers: The State Institute of Cinematography in the 1930’s. The Slavonic and East European Review, 85:3, pp. 462-490.

MUGUIRO, Carlos (2005). Reconstruyendo a Mijaíl Romm. MUGUIRO, Carlos (ed.), Ver sin Vertov (pp. 43-47). Madrid: La casa encendida.

NIZHNY, Vladímir (1962). Lessons with Eisentein. New York. Hill&Wang.

PARDO, Carmen (2002). Las formas del silencio. Ólobo, enero-diciembre (no3). Recuperado el 12 de diciembre de 2014, de https://www.uclm.es/artesonoro/olobo3/ Carmen/Formas.html

POGOZHEVA, L. (1962). Hora y media de reflexiones. Documento archivo Cinemateca de Cuba. Carpeta Mijaíl Romm. Publicado originalmente en Iskustvo Kino, 4.

ROMM, Mikhail (1965). Das wahre Gesicht des Faschismus: Interview mit Michail Romm. Sputnik Kinofestivalia, 4, 8, julio. Citado en BEILENFOFF & HÄNSGEN (2008), p. 142.

ROMM, Mikhail (1965). Fuego en el portal. Cine cubano, 26, pp. 28-33. (Publicado originalmente en Cinema 60, 40 (octubre, 1963). Traducción Alejandro Saderman.

ROMM, Mikhail (1971). Habla Mijáil Romm. Films Soviéticos, 1, pp. 30-31.

ROMM, Mikhail (1972). Director Mikhail Romm. Films Soviéticos, 9, pp.11-12.

ROMM, Mikhail (1975). Besedy o kinorezhissure. Moscow. Iskusstvo.

ROMM, Mikhail (1989). Cinco promesas. Sputkin, 4, pp. 82-88. (Originalmente publicado en Sovietski Ekran).

TUROVSKAYA, Maya (2008). Some documents from the life of documentary film. Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema, 2:2, pp. 155-165.

WOLL, Josephine (2008). Mikhail Romm’s Ordinary Fascism. KIVELSON & NEUBERGER (ed.). Picturing Russia, Explorations in Visual Culture (pp. 224-229). New Haven/London. Yale University Press.

CARLOS MUGUIRO

Professor of Film Aesthetics at the Universidad de Navarra. He curated the retrospective ‘Ver sin Vertov’ (‘To See Without Vertov’) at La Casa Encendida in Madrid in 2005-06. He was also the curator of the first retrospective of Russian film-maker Alexánder Sokurov in Spain (Festival de Creación Audiovisual de Navarra, 1999) He founded the Festival Punto de Vista, and was its Artistic Director until 2009. He has participated in numerous collective publications, such as Una diagonale baltica. Ciquant’anni di produzione documentaria in Letonia, Lituania ed Estonia, and edited books such as Ver sin Vertov. Cincuenta años de no ficción en Rusia y la URSS (1955-2005).

Nº 5 PEDAGOGIES OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Editorial. Pedagogies of the Creative Process

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTOS

The Goodwill for a Meeting: That's cinema

Excerpts by Henri Langlois, Jean-Louis Commolli, Nicholas Ray

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Filmmaker-spectator, Spectator-filmmaker: José Luis Guerin's Thoughts on his Experience as a Teacher

Alain Bergala

Filmmaker-spectator, Spectator-filmmaker: José Luis Guerin's Thoughts on his Experience as a Teacher

Carolina Sourdis

ARTICLES

In Praise of Love. Cinema en Curs

Núria Aidelman, Laia Colell

A Daring Hypothesis

Jonás Trueba

To Shoot through Emotion, to Show Thought processes. The Montage of Film Fragments in the Creative Process

Gonzalo de Lucas

The Transmission of the Secret. Mikhail Romm in the VGIK

Carlos Muguiro

The Biopolitical Militancy of Joaquín Jordá

Carles Guerra

REVIEWS

AA,VV. BENAVENTE, Fran y SALVADÓ, Glòria (ed.), Poéticas del gesto en el cine europeo contemporáneo.

Marga Carnicé Mur