SCENES FROM THE CLASS STRUGGLE IN PORTUGAL

Jaime Pena

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Even if once in a while, it is strongly recommended to return to the pages of El otro cine: recuerdo de José Ignacio F. Bourgón or, even better, to the original articles published between 1981 and 1983 by the Madrilenian critic, designer and programmer Jose Ignacio F. Bourgon (Madrid, 1951-1988) in the homonymous section of the Journal Casablanca. The volume published by Filmoteca Española in 1989 constituted a homage to one of his greatest collaborators. It consisted on a collection of articles and a cinema series that included films by, in alphabetical order, João Botelho, John Byrum, Sara Driver, Robert Frank, Amos Gitai, Jim Jarmusch, Johann van der Keuken, Robert Kramer, Manoel de Oliveira, Nicholas Ray, Carlos Rodríguez Sanz and Manuel Coronado, Alberto Seixas Santos, Jorge Silva Melo, Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, Gerhard Theuring and Ingemo Engstrom, Wim Wenders and Ivan Zulueta. The films had been made between 1959 (Pull My Daisy by Robert Frank) and 1982, although the majority dated from the late seventies and early eighties and had been addressed by Bourgon in his articles for Casablanca.1

This collection of texts and films takes us to a singular and very far time in which travelling was necessary in order to watch a determined type of films and to contact their authors. It would not be a bad idea to repeat that same series to contrast the meaning of the notion of ‘other cinema’ in the eighties and today. A number of those films are now accessible in DVD editions or at least have had certain dissemination, some others, nevertheless, still demand us to move: those films must be searched for, they do not come to us2. Among them, several Portuguese films should be referred, particularly those by Seixas Santos and Silva Melo. As the biographical text of El otro cine (not signed) explains, Bourgon had lived ‘very closely the events of the Portuguese revolution. This fact, together with the friendship with directors such as Robert Kramer and the Straub-Huillet’, lead him to a ‘radicalization of his political and cinematographic postures’3 (1989: 7). It should be clear that Bourgon does not allude in any case to the revolution of the 25th of April 1974 -The Carnation Revolution-, or to the cinema that could be derived from it. It is rather his political spirit that inspires the radicalization of certain forms of production and representation, forms that Bourgon not only brings to his texts, but also to the selection of the films and authors and to his film programming at festivals, The Filmoteca Española and The Alphaville Cinema.

To return to the pages of El otro cine with certain assiduousness have lead me to mythologise that time and, consequently, to wonder about what happened in those years in Portugal, those between the Revolution of 1974 and 1982. Thus, with this aim one writes and programs many times: simply to find the answers to some intriguing questions. In 2013 I started to prepare a large film series for the Bafici (Buenos Aires): ‘After April. Portuguese Cinema 1974-1982’. A series that was to be programmed coinciding with the 40 years of the Revoluçao dos Cravos in April 2014, and that would include around twenty films produced in this period during the years of post-revolutionary upheaval. Finally, the closure for improvements of the Lugones Cinema at The Argentinian Cinematheque postponed sine die that project that was to be nourished by the copies donated by the Portuguese Cinematheque. I resumed the programming of the series for the CGAI-Filmoteca de Galicia (A Coruña) in a more synthetic version in 2015. Problems with the availability of the prints in April and May, forced us to delay the project until October, date in which, keeping the title of the series, at last the collection of eleven films could be programmed in ten sessions. Regarding the initial Bafici project, some of the titles that could be considered more commercial and conventional or, with the perspective of time, unsuccessful (put inverted commas to all these adjectives, if it is the case), were no longer part of the series: Films by Antonio Pedro Vasconcelos, Lauro Antonio or Luis Filipe Rocha, but also by others who were more or less representative for the time such as Fernando Matos Silva, Solveig Nordlund, Luis Galvão Teles, etc. Reconsidering the extension of the film series was related to the magnitude of the Bafici and the CGAI in Buenos Aires and A Coruña. The film I most regret not having been able to include is Passagem au meio caminho (Jorge Silva Melo, 1980), which was not available in the archives of Portuguese Cinematheque, and which Bourgon had written on in Casablanca and made part of the homage series at The Filmoteca Española. As it can be seen, certain films still conserve that inaccessibility aura.

In O cais do olhar (1999) José de Matos-Cruz recorded in the period between 1974 and 1982 a total of 116 feature films, an important number for a country with a considerable reduced level of production. Matos-Cruz is generous when he attributes to the category of feature films works of less than a hour, nevertheless, some of the most significant titles of these years are not referred in his book because they are, like in the case of O constructor de anjos by Luis Noronha da Costa (1978), short films or medium-length films. The film by Noronha da Costa, converted into a mythical tittle, is one of the eleven films composing ‘After April. Portuguese Cinema 1974-1982’4. Even if the other ten feature films represent only the 8.6% of the production of those years, I consider them of an undeniable importance and relevance, above all if as I pretended they not only enable a panoramic view of the cinema of those years, but project it on the present as well, on Portuguese cinema of the following decades and why not, on certain questions of representation that the Portuguese have constantly considered and which, in different degrees, could be extended to filmmakers such as Rita Azevedo Gomes, Pedro Costa, Miguel Gomes or João Pedro Rodrigues, thus shaping some kind of national style, a truly national cinema. Of course, the style itself, highly rooted in the theatre and the novel, or at least formulating a different way to approach the traditional forms of literary representation, could be traced already in the work of Manoel de Oliveira, at least since The rite of Spring (Acto da Primavera, 1962). Simultaneously, I have always wondered about the influence, as in the case of Jose Ignacio F. Bourgon, that this retrospective of Straub-Huillet in Figuera de Foz in 1974 could have exerted in this Portuguese cinema as a whole.

Be that as it may, the film series does not have a historicist will nor its discourse is chronologically organized: its disseminative vocation always prevails. If that discourse was prioritized it would be more suitable to commit to tittles such as Benilde ou a Virgem Mãe (1973) instead of Amor de perdição (1979) as examples of the work of Manoel de Oliveira, or in the case of João César Monteiro to Que farei eu com esta espada? (1975) rather than Silvestre (1981). Certainly the film series pretends to be some kind of Greatest Hits, even if many of the represented filmmakers never had a single one and constitute, in countries like Spain, authentic strangers. Deep inside, one of the purposes of the film series was simply to show the extreme vitality of the Portuguese Cinema of the time, the variety of filmmakers who coming from very different generations (that of the sixties, that of the seventies, besides from Oliviera) converge in a concrete historical moment sharing both interest and concerns around the notion of mise-en-scène.

Hence the initial decision to choose only one film per director with the exception of the two films by Alberto Seixas Santos, for reasons I will explain later, or that in the midst of the managing of the series with the death of Manoel de Oliviera, the possibility to conclude the series with his posthumous film Visita ou Memórias e confissoes (1982) was considered. This film represents a true turning point in Oliviera’s career and I would rather say in Portuguese cinema since it defines the end of an entire era. Unfortunately, the limitation of the existing prints, and the avalanche of requests from all over the world, made its inclusion impossible. But far from being devoted exclusively to rarities, the series aimed for a combination between the most known (Oliviera, Monteiro, maybe João Botelho, Deus, Pátria, Autoridade a very popular tittle among cinema-clubs in Spain during the seventies and the eighties) and the least known or directly unknown, including films that haven been widely heard of and read about such as Trás-os-Montes (António Reis and Margarida Martins Cordeiro, 1976), but that still have had a very limited circulation in Spain. As usual, the hope is that the better known tittles awake the curiosity towards the least recognizable and that the first, at least, bring the attention of the occasional cinephile.

In general lines, the series starts with two films framed in the exact moment of the Revolution and it is structured in three strands. The first one is the change of the regime itself, Salazar’s death announced in Brandos costumes (1974), and the revision of the Estado Novo, both in the film by Alberto Seixas Santos (the documentary images of Salazarim, the family history as microcosms of a country), and in Deus, Pátria, Autoridade (Rui Simões, 1975), a militant documentary of Marxist vocation that advocates for control of the means of production by the working class5. If the political radicalization of these first revolutionary moments will decrease with the years, the cinematographic radicalization, by contrast, will be accentuated. In the second strand of the series, that of documentaries, it can be verified that the anthropological observation end up drifting to a questioning of the representation itself and to metanarratives: Gente da Praia da Vieira (António Campos, 1975), that great master piece of the cinema of the seventies that Trás-os-Montes is, and Nós por cá todos bem (Fernando Lopes, 1978), a film that Miguel Gomes himself recognizes as his main influence for Aquele querido mês de agosto (2008).

Below: Nós por cá todos bem (Fernando Lopes, 1978)

It results particularly noticeable to confirm the perfect continuity between these ‘documentaries’ and films with a strong literary component such as Conversa acabada (João Botelho, 1981), Amor de perdiçao (Manoel de Oliveira, 1979), Silvestre (João César Monteiro, 1981), and A Ilha dos Amores (Paulo Rocha, 1982), which compose the third strand of the series. If Tras-os-Montes and Nós por cá todos bem can not be understood without the precedent of The Rite of Spring, a film like O construtor de anjos, with its approximation to the fantastic so deeply rooted in Jean Cocteau, seems to foresee the universe of the much later Os Canibais (Manoel de Oliveira, 1988). Finally, as if it was an epilogue, Gestos e fragmentos – Ensaio sobre os militares e o poder (1982) is the second and indispensable film by Alberto Seixas Santos in this series: who was to shoot the first revolutionary film, would shoot as well its epitaph, a documentary in which Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho, Eduardo Lourenço and Robert Kramer6 reflect on the ‘fail’ of the Revolução. Political disappointments do not have to go by hand with those aesthetical. More than forty years after April 1974, we know that the revolution bore fruits and, what is even more important, that those fruits had continuity and still are visible in Portuguese cinema today.

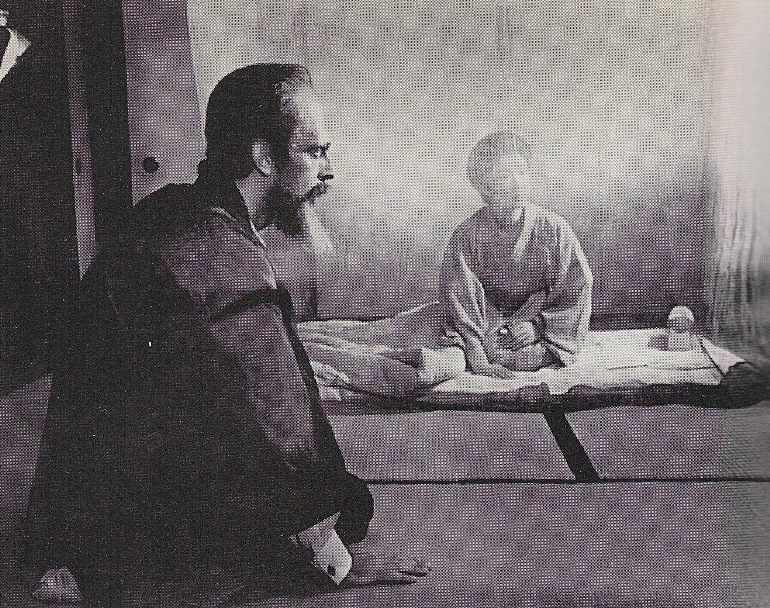

Below: A Ilha dos Amores (Paulo Rocha, 1982)

Films included in the series ‘After April. Portuguese Cinema 1974-1982’

(CGAI, 1 September – 22 October 2015)

Brandos Costumes (Alberto Seixas Santos, 1974)

Deus, Pátria, Autoridade (Rui Simões, 1975)

Gente da Praia da Vieira (António Campos, 1975)

Trás-os-Montes (António Ries and Margarida Martins Cordeiro, 1976)

O construtor de anjos (Luis Noronha de Costa, 1978)

Nós por cá todos bem (Fernando Lopes, 1978)

Amor de perdição (Manoel de Oliveira, 1979)

Silvestre (João César Monteiro, 1981)

Conversa acabada (João Botelho, 1981)

Gestos & fragmentos - Ensaio sobre os militares e o poder (Alberto Seixas Santos, 1982)

A Ilha dos Amores (Paulo Rocha 1982)

FOOTNOTES

1 / Only a film by George Kurchar is felt to be lacking.

2 / To clarify, the film by Jim Jarmusch that Bourgon commented on an article in 1981 was Permanent Vacation (1980), while in several texts of 1982 he would address Oliviera with Francisca (1981), the Straub-Huillet with Trop tôt, trop tard (1981), Nicholas Ray with We Can’t Go Home Again (1979) and Wim Wenders with Reverse Angle: New York City, March 1982 (1982), to mention some of the best known names that we can consider today as the most ‘normalized’ (this said with inverted commas and all the caution). The first chapter of “El otro Cine” (October 1981) was focused in Arrebato (Iván Zulueta, 1979) and Inserts (John Byrum, 1975).

3 / In a former paragraph we are told Bourgon personally had contact with the Straub-Huillet in the Figueira da Foz Festival in 1974: the Portuguese connection!

4 / Film series programmed in the CGAI-Filmoteca de Galicia (A Coruña) between the 7th and the 23rd of October 2015.

5 / Visita ou Memórias e confissões would have constituted a good response within the series, that of the bourgeoisie itself, since Oliviera’s family lost the control of its factory after its occupation by their workers. Oliviera would never recover economically from this, and the sale of his house, the subject, the reason of being of the film itself, was nothing more than a coincidence of that imperial need to pay off the debts he had incurred in.

6 / Precisely the author of Scenes from the Class Struggles in Portugal (1977) and, some years later, of another ‘Portuguese’ film like Doc’s Kingdom (1988).

ABSTRACT

Between April 1974, when the Carnation Revolution started, and 1982, 116 films were produced in Portugal. The Film Series Despois de abril. Cine portugués 1974-1982, gathers together and relate 11 of these films to study those post-revolutionary years of upheaval. The author shows how the series not only enables a panoramic view of the cinema of those years, but projects it on the present, on Portuguese cinema of the following decades and on certain questions of representation of that cinema. One of the purposes of the film series was to show the extreme vitality of Portuguese Cinema of the time, the variety of filmmakers who coming from very different generations (that of the sixties, that of the seventies, besides from Oliviera) converge in a concrete historical moment sharing both interests and concerns around the notion of mise-en-scène, and configuring a possible national style. In the same way, the paper observes that the radicalization of these first revolutionary moments will decrease with the years, while the cinematographic radicalization, by contrast, will be accentuated.

KEYWORDS

Film Curatorship – Portuguese cinema – The Carnation Revolution – Political and Filmic Radicalism – National Style – José Ignacio F. Bourgón – Seixas Santos – Manoel de Oliveira

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOURGÓN, José Ignacio F. (1989). El otro cine: recuerdo de José Ignacio F. Bourgón. Madrid. Instituto de la Cinematografía y de las Artes Audiovisuales.

MATOS-CRUZ, José de (1999). O cais do olhar. O cinema português de longa metragem e a ficção muda. Lisboa. Cinemateca Portuguesa-Museu do Cinema.

JAIME PENA

(Miño, A Coruña, 1965) Graduate in History of Art. Programmer since 1992 at Centro Galego de Artes da Imaxe, Galician Cinematheque. Member of the Editorial Board of the monthly journal Caimán Cuadernos del Cine (former Cahiers du Cinéma España) and usual collaborator of the Argentinian revue El Amante. Author of El espíritu de la colmena (2004), and Cine español. Otro trayecto histórico (2005, together with Jose Luis Castro de Paz); Coordinator, among others of, Edward Yang (2008), Historias extraordinarias. Nuevo cine argentino 1999-2008 (2009) and Algunos paseos por la ciudad de Sylvia (2007, together with Carlos Losilla).

Nº 6 THE POETRY OF THE EARTH. PORTUGUESE CINEMA: RITE OF SPRING

Editorial. The poetry of the earth

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

The soul cannot think without a picture

João Bénard da Costa, Manoel de Oliveira

A certain tendency in Portuguese cinema

Alberto Seixas Santos

To Manoel de Oliveira

Luis Miguel Cintra

The direct experience. Between Northern cinema and Japan

Paulo Rocha

Conversation with Pedro Costa. The encounter with António Reis

Anabela Moutinho, Maria da Graça Lobo

ARTICLES

The theatre in Manoel de Oliveira's cinema

Luis Miguel Cintra

An eternal modernity

Alfonso Crespo

Scenes from the class struggle in Portugal

Jaime Pena

Aesthetic Tendencies in Contemporary Portuguese Cinema

Horacio Muñoz Fernández, Iván Villarmea Álvarez

Susana de Sousa Dias and the ghosts of the Portuguese dictatorship

Mariana Souto

REVIEWS

MARTÍNEZ MUÑOZ, Pau. Mateo Santos. Cine y anarquismo. República, guerra y exilio mexicano

Alejandro Montiel