THE DIRECT EXPERIENCE. BETWEEN NORTHERN CINEMA AND JAPAN

Paulo Rocha

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

Questionnaire

1. What reason or reasons made you choose cinema as a form of artistic expression and what did you go through before starting to direct films?

2. How was your first film financed and in what conditions was its production carried out?

3. In relation to previous decades, and particularly the 50s, do you consider that there was a significant alteration in Portuguese cinema in the 60s?

4. Thinking about the cinema of the 60s, how do you place your movies from that period?

5. Do you consider that your films (in terms of production and aesthetics) had affiliations or received influences from international movements?

6. Do you establish any parallelisms between the films you make today and the aesthetics and production premises of Portuguese cinema in the 60s?

7. In your opinion, which are the ten best Portuguese films in history?

1. In Oporto, between the ages seven and twelve I wrote fictions, which were influenced by my chaotic juvenile readings. My father, a returned “Brazilian”, and a poet in his free time, guided me to be a writer. I discovered cinema in the Trindade, escaping from the Almeida Garrett school. I remember having seen in those times Kinugasa’s first color film, which had just won the Golden Palm in Cannes. The Japanese temptation was just starting…

I went to study Law in Lisbon, where I became friends with Nuno de Bragança, Pedro Tamen, Bénard da Costa, Alberto Vaz da Silva, people who were very linked to a non-conventional film club, the C.C.C, which took place in the Jardim Cine. Day and night, I started to imagine film plots. Between the ages nineteen and twenty-seven I must have done a hundred. I spent my life walking around, looking at houses and people. It made me sad that those people would die, I wanted to stop the river of time. The remedy was to make films. They were very visual ideas, linked to the houses, and concrete spaces. The characters would appear to me as if they were “lost souls” from those places and I were there acting as a medium. I had a great physical fragility, and everything would make an imprint on me like hot wax. I still carry obsessive scenes and images from that time that are slowly being introduced in the films I make now.

Through the engineer Neves Real I met Manoel de Oliveira in Oporto, in the times of O Pão (1959), shooting in which I did an internship. I really liked what Manoel did, although I wouldn’t be able to understand him until later on. I think Oporto is a more cinematographic city than Lisbon: look at António Reis, who is also from there, like me, and it’s not coincidence. Oporto is a “dramatic” city from the north of Europe, where the image is born at the same time as a carnal act and a synthesis of intelligence. Lisboa is already Arab, it doesn’t want drama or theatre, it wants poetry, string music, landscape painting, lyric fusion, refined sensuality. It misses the notion of the dramatic conflict, the body-to-body confrontation, the weight of the skin…

I didn’t manage to finish Law. I went to IDHEC [Institut des Hautes Études Cinématographiques], in Paris (although the SNI had rejected the compulsory presentation letter). It was the golden age of the new wave, and the Cinemateca was full of new people from all over the world. At IDHEC there was Sadoul, Mitry, Varda, Pierre L’Homme, but the teaching was uninspired. I was in debt with Renoir, watched and rewatched, and started studying Mizoguchi’s films. In those times I met a lot of people of Japanese cinema, who passed by Paris. Actors, technicians, scriptwriters. I slowly became very good friends with the great Kinugasa, and started to read everything about the Far East, and to learn the language. At IDHEC there was Cunha Telles and Costa e Silva. Telles already had a thousand ideas about the future of Portuguese cinema, and we talked about it with Margareta Mangs, a very smart swede who had a great heart and came to Portugal (married to António), where she edited Os Verdes Anos (1963) and Mudar de Vida (1966). When I finished IDHEC, I did an internship in Vienna, at The Elusive Corporal (Le caporal épinglé,1962), of my master Renoir, and I liked the man more than the artist. Right after, I helped out a bit in the making of A Caça (Manoel de Oliveira, 1964), and soon I realized that the almost unknown Manoel was as big as the great Renoir. That’s why I wasn’t surprised when, so many years later, the capitals of the world started to discover his genius.

Below: Making of Os Verdes Anos (Paulo Rocha, 1963)

2. Os Verdes Anos was the first work of C. Telles productions. António had an impressive persuasiveness, and chose the team members wisely. Without counting the French cameraman (Luc Mirot) and Paulo Renato, it was a technical and artistic team of beginners. The enthusiasm was great, but we didn’t have any experience. The film cost 600 contos (between today’s ten and twelve thousand?). I didn’t get anything, and the salaries were modest. Gasoline was cheap… and the engineer Gil, from Ulyssea Filme, was fascinated with Telles’s dynamism and gave some credit. One of Rui Gomes’s cousins came in with 100 and something contos, and Telles mortgaged one of his mother’s houses, if I remember correctly. Later on, Vitória Filme gave us 200 contos in advance for future expenses. The film ended up being sold to some foreign televisions, which would almost cover the biggest expenses. Today, the Portuguese market, although with more than a hundred thousand viewers, once the publicity is paid, doesn’t leave anything for the producer.

3. In the 50s, the traditional Portuguese films had lost its popular public, and the people from Avenidas Novas (Avenida Roma and Avenida Estados Unidos da América) were expecting something else. The 60s gave a first response: on one hand, the Produções Cunha Telles, very 'New Wave', with unknown actors, light technical teams and natural sets; on another, the prophetic heroic deeds of Manoel de Oliveira, who only filmed in the countryside and who, via Acto da Primavera (1963), announced the European avant-garde of the 70s and 80s: predominance of the theatrical scene, rediscovery of the text, new rituals. When the cinema novo decided to support Manoel (a famous lunch at Casa do Alentejo), the dynamic that Portuguese cinema has followed for the last 20 years was created. The only thing missing was the return to the studio, which would be the novelty of the next decade.

4-5. My films from the 60s have more to do with the general environment of the city (the end of Salazarism, the culture of the Avenidas Novas), than with the other cinema that was being done. I admired Fernando Lopes, but my artistic references were others. Os Verdes Anos has many subliminal tributes to Japanese cinema, but it has an almost expressionist suicide despair that gives it a weight and a darkness that come from my direct experience with people and places, without external artistic mediation. Os Verdes Anos was a kind juvenile Lisbon film only in its appearance. Mudar de Vida is my attempt at “Northern” cinema. It’s filmed in the Furadouro, land of my mother and my grandparents. The image is heavy and monumental, it goes back to being close to the Japanese and some Russian filmmaker. It’s also a matter of direct experience: since my childhood I was enchanted by the strength of those fishermen and those boats. It’s the contrary of the plastic and literary culture of Lisbon. But it’s close to Júlio Resende’s paintings. António Reis’s collaboration, in the dialogues, was decisive to achieve that environment of hieratic violence. A Caça, which I admire very much, was filmed near there.

Below: Mudar de vida (Paulo Rocha, 1966)

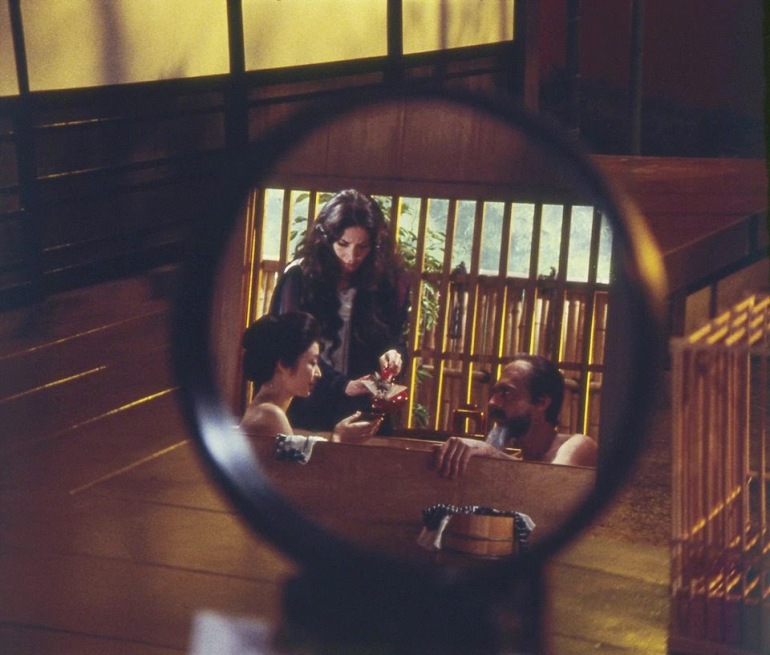

6. When I finished Mudar de Vida, I discovered the Japanese classical theatre and the avant-garde art at the same time. Invited by the Fundação, all of a sudden I had to film the new Óbidos Museum. Almost without thinking, since there was no time, I advanced on a new path, which led me to A Pousada das Chagas (1972).

A Ilha dos Amores (1982) is daughter of A Pousada (and, unconsciously, of Acto da Primavera). A Ilha and A Pousada are opera-films, neo-Kabuki, in which every element (colors, dreams, shapes, words, bodies) is exacerbated, in an aesthetics of excess that has to do with certain ways of modern art in which the waste of energy tries to re-blend the fragments of a fractured world. Le Soulier, A Ilha and A Pousada are “Modernist plays”, so close to Gil Vicente’s theatre as Glauber Rocha’s works. O Desejado (1987) will have to do with the films I didn’t make but that I wrote around Os Verdes Anos, River of Gold (O Rio de Ouro, 1998), A Viagem de Inverno, etc. The same obsessive images of running water return, and the same type of human relationships. I think that in the future I will alternate between the Ilha and the Verdes Anos styles, between the monumental fresco and the decomposed urgency of passions.

7. I’ve lived in Japan for 10 years. I haven’t seen many recent films, and I have forgotten a lot of the old ones.

Francisca (Manoel de Oliveira, 1981); Amor de Perdição (Manoel de Oliveira, 1979); A Caça (Manoel de Oliveira, 1964); Ana (António Reis and Margarida Cordeiro, 1982); Trás-os-Montes (António Reis and Margarida Cordeiro, 1976); Ninguém Duas Vezes (Jorge Silva Melo, 1984); A Canção de Lisboa (José Cottinelli Telmo, 1933); Vilarinho das Furnas (António Campos, 1970); Belarmino (Fernando Lopes, 1964); Quem Espera por Sapatos de Defunto (João César Monteiro, 1970).

Nº 6 THE POETRY OF THE EARTH. PORTUGUESE CINEMA: RITE OF SPRING

Editorial. The poetry of the earth

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

The soul cannot think without a picture

João Bénard da Costa, Manoel de Oliveira

A certain tendency in Portuguese cinema

Alberto Seixas Santos

To Manoel de Oliveira

Luis Miguel Cintra

The direct experience. Between Northern cinema and Japan

Paulo Rocha

Conversation with Pedro Costa. The encounter with António Reis

Anabela Moutinho, Maria da Graça Lobo

ARTICLES

The theatre in Manoel de Oliveira's cinema

Luis Miguel Cintra

An eternal modernity

Alfonso Crespo

Scenes from the class struggle in Portugal

Jaime Pena

Aesthetic Tendencies in Contemporary Portuguese Cinema

Horacio Muñoz Fernández, Iván Villarmea Álvarez

Susana de Sousa Dias and the ghosts of the Portuguese dictatorship

Mariana Souto

REVIEWS

MARTÍNEZ MUÑOZ, Pau. Mateo Santos. Cine y anarquismo. República, guerra y exilio mexicano

Alejandro Montiel