AESTHETIC TENDENCIES IN CONTEMPORARY PORTUGUESE CINEMA

Horacio Muñoz Fernández, Iván Villarmea Álvarez

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHORS

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Portugal is no longer the magnetic pole that attracted foreign filmmakers fascinated by its recent history –such as Robert Kramer and Thomas Harlan– or by its culture –such as Alain Tanner and Wim Wenders. On the contrary, from 2000, contemporary Portuguese cinema has become one of the most important aesthetic focal points in the international film scene, multiplying its maverick filmmakers and thus confirming the situation described by French critic Serge Daney in 1981 (2001). The difference regarding the past is that this new Portuguese cinema has become a privileged meeting point for several aesthetic tendencies of contemporary cinema, establishing overlapping and random relationships with other filmmakers, without stopping looking at the present and past of their country of origin. Its main filmmakers are developing new ways of storytelling away from conventions and commercial dictations, while their images, as Glòria Salvadó Corretger has written, ‘suggest some of the most important issues of modernity’ (2012: 8, our translation). We must not forget, however, that three generations of heterogeneous filmmakers meet in contemporary Portuguese cinema without making up a single school: the first one would be the 1990s generation, formed by Pedro Costa, João Canijo, Teresa Villaverde or Manuel Mozos; the next one would be the 2000s generation, to which João Pedro Rodrigues, João Rui Guerra da Mata, Susana de Sousa Dias, Miguel Gomes or João Nicolau belong; and finally there will be a younger generation that began to film after 2005, in which we can include Gonçalo Tocha, Salomé Lamas or Gabriel Abrantes, among others. In our opinion, if we want to grasp the importance and value of their images, we must move away from History’s synchronic and normalising models, because their relationship with each other and, above all, with the Portuguese film tradition –represented by names such as Manoel de Oliveira, Paulo Rocha, Fernando Lopes, João César Monteiro and specially António Reis– is far from being hierarchical and unambiguous.

Playing with Genres

Contemporary Portuguese filmmakers show a clear desire to experiment with genres in their films. Their games of cinema and with cinema reflect an autonomous and independent conception of this medium. Miguel Gomes and João Nicolau, for example, play with cinema and make cinema while playing, to the point that Nicolau understands these games as a way to open spaces of freedom for his characters. In a paper on the latter, Fran Benavente and Glòria Salvadó Corretger even talk about game-images arising from both the need to break with an unsatisfactory reality and the emergence of unexpected musical sequences that lead the story toward fantasy worlds. In fact, Nicolau uses music in a playful way in his whole work, whether as an element of rupture or as ‘something that can make forward the film’ (ALGARÍN NAVARRO & CAMACHO, 2012: 39, our translation). Thus, in Song of Love and Health (Canção de Amor e Saúde, João Nicolau, 2009), the Brasília Shopping Centre turns red under Shirley Collins’ music and the characters move like ghosts through its shops and hallways. This scene is quite similar to another hypnotic sequence in To Die Like a Man (Morrer como um Homem, João Pedro Rodrigues, 2009), in which the main characters went out to the forest for a wild-goose chase and become paralysed by the moon’s influence while listening to a song by Baby Dee. Again, the image turns red. In these two examples, music works as a temporal break that links reality with the oneiric and ghostly realms, but the desire to experiment with genres is better expressed in To Die Like a Man. The very beginning of this film summarises what will be, in the filmmaker’s own words, ‘a transgender film in several meanings of the word’ (ÁLVAREZ, et al., 2010, our translation). Here, the ‘trans’ aesthetic works in both a diegetic and a formal level, as happens in Pedro Almodóvar’s films, because Rodrigues mixes melodrama, war film and musical film in a work that is about sexual and genre identity. Indeed, the film’s lack of generic definition reflects the leading character’s own lack of definition: s/he is Tonia, a transsexual who does not dare to take the final step to become a woman.

Below: Morrer como um Homem (João Pedro Rodrigues, 2009)

Meanwhile, realism also allows the emergence of the fantastic and the ghostly inside it, inasmuch as this aesthetics suddenly gains an unreal, nocturnal and abstract atmosphere. A clear example would be Pedro Costa’s last feature films, Colossal Youth (Juventude em Marcha, 2006) and Horse Money (Cavalo Dinheiro, 2014), in which Ventura’s figure, as well as some gloomy locations, echo F. W. Murnau’s or Jacques Tourneur’s work. The Zombie is thus a key figure that resonates with a clear political aim in Costa’s entire filmography since Down to Earth (Casa de Lava, 1994). The main characters of his films live in the zombie’s liminal condition: they are like living deads in the hands of the system. We can even find an almost explicit allusion to this figure in the second half of the short film Tarrafal (Pedro Costa, 2007), during a conversation between Ventura and his friend Alfredo. The latter seems to be telling to the former his terrible experience in Tarrafal, a camp for political prisoners in Cape Verde, but Ventura addresses Alfredo as if he were already dead, as happens in many other sequences of Colossal Youth and Horse Money. Later on, both characters are sitting on a log outside a shack, contemplating the view of Lisbon’s outskirts. This space, like Fontaínhas, is a place disconnected from the city and suspended in time, a place 'where its inhabitants are in an interlude between life and death' (SALVADÓ CORRETGER, 2012: 242, our translation). In order to reinforce this idea, Costa himself has pointed out that the actors thought in hell while wandering around this location during the filming. (NEYRAT, 2008: 166). Accordingly, for this filmmaker, both deportees and political prisoners suffer the same situation, in which the state of exception is the rule. Under these circumstances, the space of the concentration camp, as philosophers Giorgio Agamben and Reyes Mate have pointed out, has become the symbol of modern politics.

In many other works, these experiments with genres allow a dialogue with the memory of cinema and with the Portuguese historical memory. The two films that best represent this tendency are Tabu (Miguel Gomes, 2012) and The Last Time I Saw Macao (A Última Vez Que Vi Macau, João Rui Guerra da Mata & João Pedro Rodrigues, 2012). The former establishes a clear link with silent film and American classical cinema –specifically, with Tabú: A Story of the South Seas (F. W. Murnau & Robert J. Flaherty, 1931)– while exploring Portuguese colonial history. Its prologue, narrated by Gomes himself, uses the codes of early and silent film to tell the story of a daring and taciturn explorer, tormented by his late wife, who will end up being devoured by a crocodile that will subsequently undergo his same torture: to become a sad and melancholic being. Following this line, the second part establishes clear links with several American epic films set in Africa, such as Mogambo (John Ford, 1953), Hatari! (Howard Hawks, 1962) or even Out of Africa (Sydney Pollack, 1985). Meanwhile, The Last Time I Saw Macao adopts a similar dynamic from its beginning, in which a series of leitmotivs immediately place the audience in the noir field: two feet in shiny black high-heeled shoes walking slow and steady toward the stage, the silhouette of a female figure highlighted in darkness, several tigers moving behind her, and Jane Russel’s voice singing the main theme of Macao (Joseph Von Sternberg and Nicholas Ray, 1952). From this prologue, The Last Time I Saw Macao is full of details related to film iconography, beginning with the lone shoe that already appeared in the opening sequence of Red Dawn (Alvorada Vermelha, João Rui Guerra da Mata & João Pedro Rodrigues, 2011), which reappears here as a quote to Sternberg’s and Ray’s film –the characters played by Jane Russell and Robert Mitchum met when she threw a shoe through a window that accidentally hits him.

The two main elements used by Guerra da Mata and Rodrigues to give this noir touch to their film are the labyrinthine, mysterious and strange spaces of Macao and a voiceover that recalls the first-person narratives of detective stories. In fact, the whole narrative of the film relies on these two elements, given that its characters almost never appear on the screen: we can only heard their voices and see the spaces through which they pass. Guerra da Mata assumes the role of detective, and his diction manages to convey the granitic appearance typical of the golden age of film noir, 'in which the characters’ monologues are also constructed from the mix of poetic and ironic notes; and in which the social and political commentary, despite not being absent, was not an end in itself, but part of a more elaborated and complex structure' (ÁLVAREZ, 2012: web, our translation). Moreover, the elliptical presence of one of the filmmakers within the story, as in a self-fiction, places The Last Time I Saw Macao within another genre, the essay film, given that 'all first-person narrative tends to be essayistic', according to Philip Lopate, 'because the potential for the essayistic discourse is put into action from the moment when a self begins to define its position and worldview' (2007: 68). Finally, the last section of the film introduces usual elements of sci-fi and disaster movies, thereby multiplying its discursive polysemy.

Between Documentary and Fiction

Beyond the mix of genres, The Last Time I Saw Macao also plays with a superposition of registers, between documentary and fiction, that appears in many other contemporary Portuguese films. Our Beloved Month of August (Aquele Querido Mês de Agosto, Miguel Gomes, 2008), for example, would be another film that presents this type of hybridisation by combining no less that two registers –documentary and fiction– and three genres –ethnographic documentary, family melodrama and metacinema– to thus invite the audience to mix up story and reality. In this case, the film begins as a documentary about the everyday summer life in Arganil, in Beira Alta, but another reality soon appears within this documentary, another level that tells the story o a filmmaker –Gomes himself– who is compelled to assume the impossibility of making his film. Later on, towards the middle of the film, a third level rises, and then Our Beloved Month of August becomes the fiction that sought to be: a romantic melodrama in which two teenage cousins face the girl’s father’s objection regarding their relationship (CUNHA, 2014: 122).

The documentary register is also mixed with fiction in João Canijo’s work: In Blood of My Blood (Sangue do Meu Sangue, 2011), real locations, non-professional actors and sequence shots reinforce the realism of the story, an inquiry into the socio-economic identity of a working-class family. Canijo benefits from the lightness and low cost of digital technology to strengthen the documentary side of fiction, thereby allowing a new relationship with the time and the space of the filming. The possibility of waiting makes easier the inscription of the real into a fictional universe, as well as the inscription of fiction into the real world. Similarly, in the case of Pedro Costa, Cyril Neyrat has stated that what is most disturbing in In Vanda’s Room (No Quarto da Vanda, 2000) is the fact that such a harsh reality is linked to fiction through issues of diction, mise-en-scène or lighting: 'the words ‘fiction’ or ‘documentary’ fall apart because perhaps we have the strongest of documentaries, but with a construction and a kind of belief that entirely come from fiction, from a fictional tradition' (NEYRAT, 2008: 82, our translation). Colossal Youth, however, is located at the fictional side of documentary fiction by assuming a more radicalised style. In this film, the rewriting of the real leads Costa to develop a series of situations in which reality is stylised and becomes an image on the verge of abstraction (QUINTANA, 2011: 159). According to Àngel Quintana, this change is symptomatic in contemporary cinema: 'at a time when everything can become an image, the essential question is to see how these fictional images, which have not lost its original documentary nature, may be considered as the recreation of a world that they render more visible' (ibid.: 161, our translation).

The work of these filmmakers shows that the difference between documentary and fiction does not depend on the fact that the former is on the side of the real and the latter on the side of the imagination. Documentary, as Jacques Rancière points out, no longer addresses the real as an effect to be produced, but as a fact to be understood: 'The real always is a matter of construction, a matter of "fiction"' (2010: 148). Fiction, meanwhile, does not give rise to an imaginary world opposed to the real one, but to 'a way of changing existing modes of sensory presentations and forms of enunciation; of varying frames, scales and rhythms; and of building new relationships between reality and appearance, the individual and the collective' (ibid.: 141). This voluntary lack of definition of the border between documentary and fiction ultimately entails a mutation in the principles of film history that have favoured fiction –and storytelling– as an essential element, thus suggesting a new genealogy for contemporary cinema, whether at a Portuguese or at a global level.

Reviewing the Archive

Reality not only enters the images through live recording, but also through the process of reviewing different types of archives. Lusitanian Illusion (Fantasia Lusitana, João Canijo, 2010), for instance, re-edits propaganda newsreels made between 1939 and 1945, primarily focusing on those images showing the armed forces and the major events organized by the Estado Novo. These newsreels staged a sweetened representation of the time that is later questioned by Canijo by means of a series of texts written by political refugees in transit through Portugal that expose the delusion of such idyllic image.

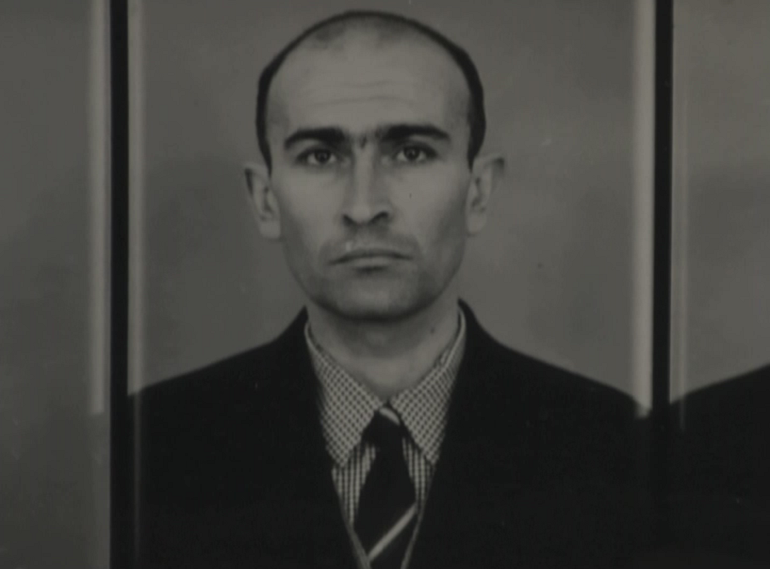

Susana de Sousa Dias’ work is also the outcome of reviewing the Salazarist archive. Natureza Morta (2005), her second documentary feature, is composed of images from state newsreels and police archives without any commentary. In this sense, her work is more material than Canijo’s, inasmuch as she seeks to create a slight sense of estrangement through formal procedures. She aims to show the hidden face of dictatorship through its own images, so she reframes, slows down and ultimately plays with this footage. Her next film, 48 (Susana de Sousa Dias, 2009), is mostly composed of mug shots, over which she superimposes the prisoners’ voices recalling their imprisonment and especially the torture they were subjected to by the PIDE (Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado –International Police and State Defence). Thus, Susana de Sousa Dias uses the victims’ faces to draw attention to a memory relegated to oblivion (AMBRUÑEIRAS, 2013: 179).

48 consciously echoes the mug shot aesthetics, in which the face becomes a document for identification, social control and discipline purposes. Iván García Ambruñeiras explains that the filmmaker forces this objective aesthetics through an intensive exploration of the faces: 'every little picture is magnified by the size of the screen and the length of the shot' (ibíd.: 178, our translation). On the one hand, slowing down the images allows the audience to peruse these documents; on the other hand, reframing them challenges the positivist institutional frame and the anonymity of faces. According to Georges Didi-Huberman, playing with the frame is the easiest way for the photographic apparatus to trigger the crisis in the institutional apparatus: 'It is enough with a slight movement while zooming in or out –whether voluntary or not– to expose the system’s excess or to produce a misframing –in terms of symbolic framing– that leaves room for imagination' (2014: 72, our translation). By slowing down the images to the 1% in the editing room, Susana de Sousa Dias made these movements almost imperceptible. In fact, without this effect, the film should last 7 minutes instead of 93: 'These seven minutes', the filmmaker explains, 'were adapted to the length of the interviews' (DIAS, 2012: web, our translation).

The police status of mug shots is also challenged through the testimonies arising from the encounter between the victims and their old faces: every image entails a series of memories and a personal story that had been repressed by official history. By locating these stories into a chronological macro-structure, the filmmaker would perfectly fit into the profile of what Miguel Á. Hernández-Navarro has named ‘the artist as a Benjaminian historian’. For this artists, according to him, history is an act of remembering, 'a way of intervening in the past and taking a stand in the present, but also an act of history, a writing of time, an embodiment of the past in the present' (2012: 42). From this perspective, Susana de Sousa Dias’ work with police archives and oral memory reveals that the real face of history has always been the neglect of victims.

Other younger filmmakers, such as Miguel Gomes or Gonçalo Tocha, also work with the archive: Gomes has ironic and redeeming intentions, while Tocha aims to create a film archive of future memories for the Corvo Island. The former resorts to found footage in his short film Redemption (Miguel Gomes, 2013), whose commentary consists of four personal letters read by different voices in different languages: Portuguese, Italian, French and German. The Portuguese colonial past reappears in he first letter through a series of images shot in Portugal in the early 1970s, over which a children’s voice read a letter addressed to his parents, who are settlers in Africa, telling them how life goes on in the mother country after returning from the colonies. Later on, in the second letter, which is read in Italian, a man recalls an old teenage love; in the third, in French, a father apologises to her daughter for his continued absences; and finally, in the last letter, in German, a women recalls her wedding day in 1976 and the first time she saw Richard Wagner’s opera Parsifal (1882). We do not know the identity of the senders until the end of the film, when we are forced to rethink the images and the privacy of the speeches, because they are Pedro Passos Coelho, Nicolas Sarkozy, Silvio Berlusconi and Angela Merkel. The feelings expressed by these four politicians have Gomes’ usual playful and ironic touch. The emergence of fiction at the end of the film, as well as the mixture of materials of different origin, destabilises the original content of images, which Gomes uses in a performative way: he creates a new film from previous footage in which the fictional speeches favour a political reading between humour and bitterness (WEINRICHTER, 2009: 105).

Regarding Gonçalo Tocha, his footage filmed for the documentary It’s the Earth Not the Moon (É na Terra não é na Lua, 2011) in the Corvo Island –the smallest and the farthest of Azores archipelago– automatically becomes the only existing archive in the island, because it lacked any other previous audiovisual record, as the filmmaker himself has explained:

'This is the reason why I sensed that everything I recorded was special and significant. I always filmed the changes in the buildings or the arrivals and departures of people, because I had the feeling that all that footage would remain for a future memory. And as I have everything classified by dates and events, I came to think that I would not make a film, but a giant archive on Corvo Island. I even had the idea of staying there for ten years to film it' (PAZ MORADEIRA, 2014: 194, our translation).

Archives are usually conceived as a means of preserving the past in the present, but they are simultaneously machines that carry the present into the future, as Boris Groys explains (2014: 147). Accordingly, being impossible to preserve Corvo Island’s past, Tocha develops a documentary device able to establish a dialogue with the future.

The Aesthetics of Distance

It’s the Earth Not the Moon begins with the filmmaker’s arrival at the island, which symptomatically appears on the screen for the first time as viewed from the sea. In Espectres del Cinema Portugués Contemporani, Glòria Salvadó Corretger states that the presence of the sea has always been a constant in Portuguese cinema: 'a sea that stands as a container of crossed times, of History, of death, linked to a literary substratum and a legendary, mythological imaginary' (2013: 84, our translation). In this sense, the image of the sea, associated with the idea of travelling and the desire for distance, reappears in many recent Portuguese titles: in Balaou (Gonçalo Tocha, 2007), the filmmakers embarks on a journey from Azores to Lisbon aboard a small sailboat skippered by a couple for whom the maritime drift has become their lifestyle. Tocha had moved to the São Miguel Island in search of his roots after the death of his mother, but his return to the continent, to Lisbon, has no arrival day. According to Beru, the ship’s captain, you have to have time on a sailboat, because you can never go faster than the wind. During the ocean crossing, Tocha repeatedly wonders 'why I went to the Azores? why I’m in this boat?', but the answer, his desire for distance, precedes the journey: 'I just want to leave', he says after fifteen minutes of film, 'go straight and remain trapped at sea'. As seen above, Tocha will come back to the Azores in It’s the Earth Not the Moon, but this is not a sea film, although it does include a return to what the filmmaker calls 'an imaginary unknown': the film, while expressing the need to create a memory and an archive in the Corvo Island, also alludes to the old journeys of imaginary anthropology. The very title echoes the stories of lunar travels as the example par excellence of distance: the moon appears here as a remote, distant, fantastic and mythological place, which may also be familiar (PRETE, 2010: 186).

In João Nicolau’s films, the same desire for distance is associated with the desire for adventure and the need to escape from everyday life. As explained by Fran Benavente and Glòria Salvadó Corretger, the journeys of the Portuguese sailors, to whom Manoel de Oliveira dedicated a trilogy a well-known trilogy –Word and Utopia (Palavra e Utopia, 2000), The Fifth Empire (O Quinto Imperio, 2004) and Christopher Columbus, The Enigma (Cristóvão Colombo – O Enigma, 2007)– also echo in The Sword and the Rose (A Espada e a Rosa, João Nicolau, 2010). Nicolau’s films, however, are closer to João César Monteiro’s –with whom he worked as assistant– especially regarding the representation of the sea: according to Benavente and Salvadó Corretger, The Sword and the Rose might be considered the flip side of Hovering Over the Water (À Flor do Mar, João César Monteiro, 1986), 'because the film seems to have been constructed to show what constitutes a disturbing and mysterious offscreen in Monteiro’s film: life aboard a ghost ship' (2014: 155, our translation). Manuel, the leading character in The Sword and the Rose, embarks on a fifteenth-century caravel in order to escape from a routine, boring and almost hostile present. His dissatisfaction with this kind of life feeds his desire for adventure and his decision to join a pirate community, thereby leaving his job and the memory of a failed relationship behind. In Balaou, the drawing of a pirate appeared superimposed in the image while the sailboat captain told the filmmaker that they still exist. In The Sword and the Rose, the new pirates travel in a caravel and 'can have all the necessary goods and provisions' thanks to a fanciful substance: Plutex (ALGARÍN NAVARRO y CAMACHO, 2012: 41, our translation). Towards the end of the film, the former pirate Rosa offers them the paradise they were looking for, a place in which they can find 'dream, love, art and science, literature, music, technology, coffee and rum':

'The end is almost Edenic. Nothing is missing, they seem to have everything in that wonderful propriety. However, for some reason, that is not enough for Manuel, so he leaves with the map and we assume that he has to look for other things. It is the same that made him leave his former life. Hence, when introducing the film, I speak a little about utopias, but also about perdition' (ALGARÍN NAVARRO y CAMACHO, 2012: 41, our translation).

This illusion of change and utopian otherness seems to be exhausted once summer and journey have come to an end, giving rise to a feeling of melancholy that can only be appeased by the idea of returning in a geographical and chronological sense. This is the reason why the journey, in The Last Time I Saw Macao, transports the filmmakers not only to the Far East, but especially to their personal past and to the distant days of Portuguese colonialism. João Rui Guerra de Mata actually spent his childhood in Macao, so the camera visits his places of memory while his character is looking for his friend around the city: his old house, his school, the restaurant where he used to eat with his parents... For him, returning to Macao means returning to the happiest period of his life, a way to recover his lost memories. Consequently, his commentary conveys a strong sense of nostalgia in which familiar images are intermingled with the strangeness of visiting a world detached from ours, whose sign system is completely alien to us.

Conclusion: International Relations

All these aesthetic links and visual resonances between different Portuguese filmmakers have led –along with other links of a professional nature born of necessity, pragmatism and friendship– to an interconnected network that have recently replaced what was previously understood as a national cinema. Thus, despite being deeply rooted in their country of origin, contemporary Portuguese cinema is constantly establishing links with other national cinemas: for example, Miguel Gomes’s and João Nicolau’s return to childhood in some of their works, such as The Face You Deserve (A Cara que Mereces, Miguel Gomes, 2004) or A Wild Goose Chase (Gambozinos, João Nicolau, 2013), echoes Wes Anderson’s universe; the presence of conspiracies and plots in Nicolau’s films takes us back to Jacques Rivette’s; Gomes’ tendency to conceive his works as the sum of several parts places him close to Apichatpong Weerasethakul; his performative use of found footage in Redemption bears a clear resemblance with Human Remains (Jay Ronsenblatt, 1998); the review process of the film image of dictatorship undertaken by both João Canijo in Lusitanian Illusion and Susana de Sousa Dias in her whole work coincides in time with Andrei Ujică’s similar work in Romania; the usual (con)fusion between documentary and fiction in Pedro Costa’s films is also present in Jia Zhang-ke’s, Naomi Kawase’s, Sharon Lockhart’s or Lisandro Alonso’s, among others; and finally, the vanishing places of In Vanda’s Room locate Costa close to other contemporary filmmakers, such as José Luis Guerín, Wang Bing o Jia Zhang-ke, who have felt the need –or the obligation– to film processes of urban change and for whom ruins have become a metaphor for the spatial violence in late capitalism.

These international relations, even if they are not fully aware, locate Portuguese cinema within the transnational framework that characterises the contemporary audiovisual scene. The separate compartments of the past currently become overlapping networks that extend from the local to the global. In this regard, any current research on Portuguese cinema has to go beyond the study of a group of filmmakers only obsessed and absorbed with their own identity to understand their position within those networks. Arguably, therefore, Portuguese cinema brings together some of the key trends in contemporary cinema, such as the aforementioned play with genres, the mixture of documentary and fiction, the critical revision of archival footage and the voluntary escape to fantasy worlds. These tendencies, however, are not exclusive of Portuguese cinema, but shared with other national cinemas that also have a clear transnational orientation. From this example, we can conclude that the future of small national cinemas depends on their greater or lesser degree of connection with large global aesthetic networks: thus, the greater the connection, the greater the distribution of films. This would then be the best way to improve the position of countries and cultures in the current geopolitics of cinema.

ABSTRACT

Contemporary Portuguese cinema has become a privileged meeting point for several aesthetic tendencies inherited from film modernity. Filmmakers such as Pedro Costa, João Canijo, João Pedro Rodrigues, João Rui Guerra da Mata, Miguel Gomes, João Nicolau, Susana de Sousa Dias and Gonçalo Tocha, among others, have developed new forms of storytelling away from mainstream conventions, in which they suggest the possibility of joining national identity and transnational links. This paper, therefore, aims to discuss some of the main aesthetic features shared by these filmmakers, such as the experimentation with genres, the mixture of documentary and fiction, the critical revision of archival footage and the aesthetics of distance. These links have strengthened the position of Portuguese cinema in the interconnected network of reciprocal influences that has recently replaced the old paradigm of national cinemas. Arguably, then, contemporary Portuguese cinema addresses national issues as part of an ongoing dialogue with other film industries.

KEYWORDS

Portuguese Cinema, Film Genres, Documentary Fiction, Film Essay, Archival Footage, Aesthetics of Distance, National Cinemas, Transnational Film

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ALGARÍN NAVARRO, Francisco i CAMACHO, Alfonso (2012). 'Entrevista con João Nicolau: Aquí tenemos de todo: sueño, amor, arte, ciencia, literatura, música, tecnología, café y ron'. Lumière Nº 5, pp. 29-48. http://www.elumiere.net/numero5/num05_issuu.php

ÁLVAREZ, Cristina; LAHERA, Covadonga G., CORTÉS, Jesús (2010). 'Entrevista a João Pedro Rodrigues', Cine Transit, (14, April 2015) retrieved from http://cinentransit.com/entrevista-a-joao-pedro-rodrigues/

ÁLVAREZ, Cristina (2012). 'A Ultima Vez Que Vi Macau. The Macao Gesture.' Cine Transit, (27, November 2014) retrieved from http://cinentransit.com/a-ultima-vez-que-vi-macau/

AMBRUÑERIAS, Iván G. (2014). 'Explorando la memoria traumática: Susana de Sousa Dias y el archivo salazarista'. MUÑOZ FERNÁNDEZ, Horacio and VILLARMEA ÁLVAREZ, Iván (ed.). Jugar con la memoria: el cine portugués en el siglo XXI (pp.162-186). Cantabria: Shangrila.

BENAVENTE, Fran and SALVADÓ CORRETGER, Glòria (2014). 'Showtime! Jugar con João Nicolau'. MUÑOZ FERNÁNDEZ, Horacio and VILLARMEA ÁLVAREZ, Iván (ed.). Jugar con la memoria: el cine portugués en el siglo XXI (pp.136-162). Cantabria: Shangrila.

CUNHA, Paulo (2014). 'Miguel Gomes, el cinéfilo.' MUÑOZ FERNÁNDEZ, Horacio and VILLARMEA ÁLVAREZ, Iván (ed.). Jugar con la memoria: el cine portugués en el siglo XXI (pp.108-136). Cantabria: Shangrila.

DANEY, Serge (2001). La maison cinéma et le monde. 1. Le Tempes des Cahiers. Paris. P.O.L.

DIDI-HUBERMAN, Georges (2014). Pueblos expuestos, pueblos figurantes. Buenos Aires. Manantial.

GROYS, Boris (2014). Volverse público: las transformaciones del arte en ágora contemporánea. Buenos Aires. Caja Negra.

HERNÁNDEZ NAVARRO, Miguel Á. (2012). El artista como historiador (benjaminiano). Murcia. Micromegas.

LOPATE, Philip (2007). 'A la búsqueda del centauro: el cine-ensayo'. WEINRICHTER, Antonio (ed.) La forma que piensa. Tentativas en torno al cine ensayo (pp.66-89). Navarra: Gobierno de Navarra, Festival Internacional de Cine Documental de Navarra.

MORADEIRA PAZ, Víctor (2014). 'Gonçalo Tocha, un cineasta insula'. MUÑOZ FERNÁNDEZ, Horacio and VILLARMEA ÁLVAREZ, Iván (ed.). Jugar con la memoria: el cine portugués en el siglo XXI (pp.186-198). Cantabria: Shangrila.

NEYRAT, Cyril (ed.) (2008). Un mirlo dorado, un ramo de flores y una cuchara de plata. Barcelona. Intermedio

PRETE, Antonio (2010). Tratado de la lejanía. Valencia. Pre-textos.

QUINTANA, Àngel (2011). Después del cine. Imagen y realidad en la era digital. Barcelona. Acantilado.

RANCIÈRE, Jacques (2010). El espectador emancipado. Pontevedra. Ellago Ediciones.

SALVADÓ CORRETGER, Glòria (2012). Espectres del cinema portuguès contemporani: Història i fantasma en les imatges. Mallorca. Lleonard Muntaner.

SOUSA DIAS, Susana de (2010). 'Cinèma du Réel: Susana de Sousa Dias (II) 48, de Susana de Sousa Dias por Susana de Sousa Dias.' Lumière¸ (27, November 2014) retrieved from http://www.elumiere.net/exclusivo_web/reel12/sousa_02.php

WEINRICHTER, Antonio (2009). Metraje encontrado. La apropiación en el cine documental y experimental. Navarra. Gobierno de Navarra, Festival Internacional de Cine Documental de Navarra.

HORACIO MUÑOZ

Horacio Muñoz holds a Ph. D. in philosophy and a degree in Audiovisual Communication from the Universidad de Salamanca. He usually writes for the online film journal A Cuarta Parede and the blog laprimeramirada.blogspot.com.es. He has published papers in journals such as Archivos de la Filmoteca, Cine Documental or Caracteres, has contributed to several volumes -for example, Las distancias del cine (Shangrila,2014) or Pier Paolo Pasolini, Una desesperada vitalidad (2015)- and has co-edited the book Jugar con la Memoria. El Cine Portugués en el Siglo XXI (Shangrila, 2014). This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

IVÁN VILLARMEA

Iván Villarmea works as visiting professor at the Universidad Estatal de Milagro, in Ecuador, where he teaches Film Language and Production. He holds a Ph.D in History of Art from the Universidad de Zaragoza, as well as a degree in Journalism and another in Contemporary History from the Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. He has recently published the book Documenting Cityscapes. Urban Change in Contemporary Non-Fiction Film (Wallflower Press, 2015) and co-edited the volume Jugar con la Memoria. El Cine Portugués en el Siglo XXI (Shangrila, 2014). Moreover, since 2013, he co-directs the online film journal A Cuarta Parede. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Nº 6 THE POETRY OF THE EARTH. PORTUGUESE CINEMA: RITE OF SPRING

Editorial. The poetry of the earth

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

The soul cannot think without a picture

João Bénard da Costa, Manoel de Oliveira

A certain tendency in Portuguese cinema

Alberto Seixas Santos

To Manoel de Oliveira

Luis Miguel Cintra

The direct experience. Between Northern cinema and Japan

Paulo Rocha

Conversation with Pedro Costa. The encounter with António Reis

Anabela Moutinho, Maria da Graça Lobo

ARTICLES

The theatre in Manoel de Oliveira's cinema

Luis Miguel Cintra

An eternal modernity

Alfonso Crespo

Scenes from the class struggle in Portugal

Jaime Pena

Aesthetic Tendencies in Contemporary Portuguese Cinema

Horacio Muñoz Fernández, Iván Villarmea Álvarez

Susana de Sousa Dias and the ghosts of the Portuguese dictatorship

Mariana Souto

REVIEWS

MARTÍNEZ MUÑOZ, Pau. Mateo Santos. Cine y anarquismo. República, guerra y exilio mexicano

Alejandro Montiel