GERTRUD KOCH. 'SCREEN DYNAMICS. MAPPING THE BORDERS OF CINEMA'

Volker Pantenburg and Simon Rothöhler (Ed.), SYNEMA - Gesellschaft für Film und Medien, Vienna, 2012, 181 pp.

Gerard Casau

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ARTICLE

ARTICLE

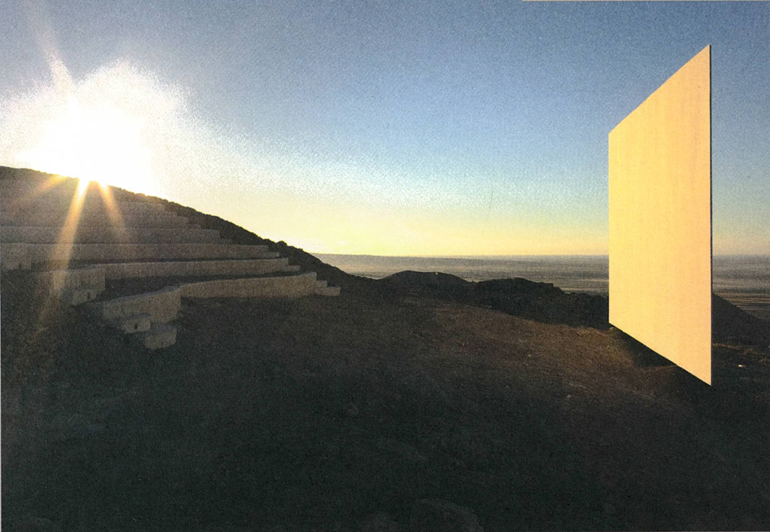

The cover of Screen Dynamics is illustrated by a photograph of Clemens von Wedemeyer’s art work Sun Cinema. Located on the outskirts of the southern Turkish city of Mardin, the giant screen serves as a community cinema which can project shadows during the day and reflect the sunset and lights of the nearby city at night. In their preface, the editors talk about the suitability of this image as the leitmotiv of the book and the subjects it seeks to address, as it is a case where “the cultural technique of ‘cinema’, with its basic setting of projector, screen and spectator, a communal and social space, is being (re-)enacted at the periphery of the Occidental world […] also the result of a project in the tradition of Land Art, conceived and realized by a contemporary artist –an indication that, for more than two decades, a considerable amount of moving images along with the discourse around them has expanded from cinema and film theory to other institutional and discursive spaces” (2012: 5).

While Bazin wondered about what cinema was, the question most often posed in Screen Dynamics is “where is cinema?” The book thus devotes itself to a scenario in which the multiplicity of devices and screens (both public and private) discuss the validity of continuing to identify cinema with the basic principles of “projector, screen and viewer” quoted above. It discusses the space occupied by the images we draw from a variety of sources, rather than the much vaunted “death of cinema”; and whether, ultimately, we can blithely continue to use the term “cinema” as a general description of the act of seeing moving images or, on the contrary, we should turn our attention to creating increasingly specific words and do so with conviction.

The first stumbling block encountered by a work of these characteristics –whose central theme appears to be inseparable from the “here and now”– is the risk of meeting head-on what appears to be highly innovative but may not actually be so. When all is said and done, the ideas mooted in the above paragraphs could also be suitable for a contemporary text about the birth of television, or a meditation on seeing the Velvet Underground give a concert, their bodies bathed in the images of a film by Andy Warhol. This is why it is to be welcomed that the essays gathered in its pages (most of them taken from the talks given during the congress “Cinema Without Walls. Borderlands of Film”, held in Berlin in spring 2010) cover a broad thematic spectrum: from the definition of “the memory of the cinephile” propounded by Raymond Bellour and which defines (or used to define?) the viewer; through Simon Rothöhlerun’s analysis of Michael Mann’s use of digital cinematography; to the use of film in contemporary theatre featured in Gertrud Koch’s contribution.

Most of the filmmakers look at the themes addressed not so much from a distance but with the prudence of the person who knows that any conclusion they may reach will always be provisional, and subject to revision. Nevertheless, we do find some examples where overenthusiasm makes the text appear somewhat naïve. This is the case with Jonathan Rosenbaum, who in his attempt to map the dawn of a new cinephilia provides a plethora of figures and statistics that sing the praises of the internet, free access (either legal or illegal) to the cinematic heritage and the almost infinite possibilities of on-line criticism. Rosenbaum’s point of view is by no means reprehensible but his obsession with details (the emergence of highly specialised cinema clubs in different towns in Argentina) means he tiptoes around the underlying question behind this so-called “new cinephilia”. However, this is only a slip-up, albeit irresolute, in a cinematic education whose cornerstones remain rooted in the pre-internet era, which encounters an offer that can rearrange any previous canons.

It is Rosenbaum himself who recognises that we are in “a transitional period where enormous paradigmatic shifts should be engendering new concepts, new terms, and new kinds of analysis” (2012: 38). He may be right, as he would have been had he written these words a decade ago when he published Movie Mutations, or even before that. This is what has made the critical exercise a kind of dialogue of the deaf between Vladimir and Estragon, as they wait for the future to make everything all right while around them nothing changes. This is why the most interesting passages in Screen Dynamics show the authors as being fully integrated into new technological habits, such as the chapters by Ute Holl and Ekkehard Knörer about the experience of watching films on the internet and on portable devices. Just as interesting are the essays by writers who capture the friction between past and present, like Simon Rothöhlerun, who describes the impossibility of detaching himself from a certain feeling of strangeness while watching Public Enemies (Michael Mann, 2009), a film set in the 1920s but whose digital photography generates a rabidly “anti-historical” way of evoking the past: “Digital reception can provide an irritating experience of presentness, enabling the audience to intuitively sense what these old-fashioned cars, steam locomotives and rough tweed fabrics would have felt like when they were ultra-modern and contemporary, that is, the high-tech and high fashion of objects of their time. In part, this intense sort of contemporary sensation is surely also a product of sheer ‘newness’, of the encounter with a high-resolution image whose properties –the ‘non-filmic’ sharpness, for instance– are mostly known from the screens installed in art museums” (2012: 146).

Despite the variety of subjects dealt with throughout Screen Dynamics, it isn’t hard to detect that the key question within its pages is the one that none of the writers dares to say aloud, maybe because they are afraid of being labelled as apocalyptic: what will become of the cinema once stripped of those elements that used to be part of its rituals? In his essay, Raymond Bellour remembers the words of Godard and Fellini, who defined cinema as something greater than us that makes us look up. Nevertheless, several chapters in the book describe a series of cinephile habits that involve tiny screens and films that people don’t go “to see”, but reach us through the transmission of data without requiring any “physical” effort on the part of the viewer. The editors say that they didn’t want to air the recurring idea of the “death of the cinema”, but no matter how stimulating the horizons of Screen Dynamics are, they also place a question mark over the issue that would provide enough material for a second volume: How much will the cinema matter once it adapts to its new screens and takes on board the fact that it is smaller than the viewer? How will it amaze and captivate us if deprived of the invitation extended by an actress’s enormous fleshy lips? These are the questions encountered at the crossroads where we currently find ourselves, where the cinema continues to belong to the big screen in the popular imagination, but whose reality and consumption seems to be firmly heading in other directions.

Translated from Spanish by Mark Waudby

Nº 3 WORDS AS IMAGES, THE VOICE-OVER

Editorial

Manuel Garin

DOCUMENTS

As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty

Jonas Mekas

The Word Is Image

Manoel de Oliveira

Back to Voice: on Voices over, in, out, through

Serge Daney

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Sounds with Open Eyes (or Keep Describing so that I Can See Better). Interview to Rita Azevedo Gomes

Álvaro Arroba

ARTICLES

Further Remarks on Showing and Telling

Sarah Kozloff

Ars poetica. The Filmmaker's Voice.

Gonzalo de Lucas

Voices at the Altar of Mourning: Challenges, Affliction

Alfonso Crespo

Siren Song: the Narrating Voice in Two Films by Raúl Ruiz

David Heinemann

REVIEWS

Gertrud Koch. Screen Dynamics. Mapping the Borders of Cinema

Gerard Casau

Sergi Sánchez. Hacia una imagen no-tiempo. Deleuze y el cine contemporáneo

Shaila García-Catalán

Antonio Somaini. Ejzenštejn. Il cinema, le arti, il montaggio

Alan Salvadó