CONVERSATION WITH PEDRO COSTA. THE ENCOUNTER WITH ANTÓNIO REIS.

Anabela Moutinho and Maria da Graça Lobo

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

Following the interview you granted us for the catalog Os Bons da Fita—in which you spoke quite a lot about António Reis’s role in your personal and professional life—we would like you to talk about this topic in more detail, particularly about the fact that you were a student of António Reis.

I started Film School in the year ’79 or ’80 (I don’t really remember, although I’m sure I finished in 1983 as the degree was supposed to be three years long). The School, which was still “hungover” from April 25th, didn’t have an organization chart, programs or a stable faculty; on the contrary, it had a series of employed professors that were normally replaced after a few months, so there were big changes in this sense… In fact, there were even professors that almost never showed up, like António Pedro Vasconcelos—who was supposed to teach Editing—or others who disappeared completely, such as Jorge Alves da Silva, who no one knows who he is nowadays but nevertheless taught Film Analysis. And we had three or four technical subjects—Photography, Sound and aspects related to Acoustics, with Alexandre Gonçalves who is still a teacher today—, that were more or less maintained, perhaps because they were taught by technicians, down-to-earth people, so to speak. And the two or three professors that I liked the most and with whom I learned the most: João Bénard [da Costa], who taught History of Film (obviously) and who wasn’t very regular but at least had us watch films (there was an agreement with what in those times was the IPC that granted the display room to the School for didactic purposes) and discuss them and write papers about them; or João Miguel Fernandes Jorge, who taught a kind of Seminars, long, about something vaguely poetic and applied to cinema (it was, on the other hand, very beautiful, as João Miguel was—and is—an excellent teacher); and António Reis.

António Reis was someone whom I did not know. In fact, I didn’t know anything about Portuguese cinema; and that which I watched—alone, in those local cinemas that existed in those times, like the one in my neighborhood (Arroios)—allowed me to mainly access “old films” of John Ford, Raoul Walsh, etc. Therefore, I arrived to the School without prejudices [in relation to Portuguese cinema] but also arrogant and insolent. For me, Portuguese cinema was those comedies of the 40s (which I personally hate; I don’t see any quality in them and I consider them completely fascist, without any interest) and, as for the Cinema Novo of Paulo Rocha and Fernando Lopes, I had only a vague idea after watching Os Verdes Anos (Paulo Rocha, 1963). I had watched it on television or because of my parents’ influence—especially my father’s—and from the film I obviously remembered Isabel Ruth, who I consider a type of Portuguese Anna Karina, the most beautiful girl in Portuguese cinema. And that was all.

So, I arrived at the School with a childhood friend; we both saw an ad in the paper and decided to quit our degrees (his was History and mine Literature). Our interests were mainly the punk music and philosophy of those times (violence, etc.), and so we soon chose to sit at the end of the classroom, hating everyone, provoking as much as we could and doing everything we could to be loathed. It was very funny, because the environment at the School was very favorable for us to “win.”

But why?

Because it was absolutely idiotic. That is, we lived the “terror” of structuralism. And although it’s true that there is no better cinema historian than Gilles Deleuze, we lacked simplicity. The student that was considered the best in the School (who pointed at us saying ‘That one over there is a genius…!’) was a 22-year-old guy, with Bataille under his arm… ‘Be careful! He has done a 40-second short film which is absolutely relevant…!’ For us this was disgusting, and even because shortly after someone wrote on a wall that he was homosexual, or things like that… Things that are still written!

And now…

For example, there was an Italian producer, about whom I read a lot, which had done peplum films, Cottafavi. I loathed his movies, but I had seen quite a few at the Roma and the Alvalade… Now, the School “was” Straub, Ozu, Godard… So I decided to write, with huge red letters (and it’s still there) “To the best Ozu I oppose the worst Cottafavi.” It was around this time that Reis started “winking” at us… During lessons we were very quiet, we never took part in them… Well, rather in some lessons, because in Reis’s I started being scared…

Of…?

Of not being able to follow him. I saw that he was a “giant.” João Miguel [Fernandes Jorge] was much more approachable, because of his age and his interest for rock music, that brought together people from the 20s and 30s generation, since that music included English and American authors that went over to cinema, art or theatre. We ourselves also played; I did posters, another guy, a graphic artist, he wrote novels, many did paintings... Everything had to do with two or three slogans or words: “violence,” “poetry,” “brutality,” “passion”… Now, while João Miguel was more close to us, António Reis was more distant, first of all because he was a country guy, who had the mark of the land, from how he dressed to the kind of cigarettes he smoked… Without filters, obviously, sometimes “Definitivos”… I remember the change towards the “SG Filter”…

But why? What was so special about it?

Nothing really, it’s just one of those details that come to mind when people die, and we remember certain gestures or fragments… For example, in the time we are talking about—by then we knew each other very well—he had brought his daughter so that I could portray them. The photo came out badly, it was all black and… he gave me a blow, ‘You have to change profession.’ After that I secretly took another one, which by chance came out well, and that’s why I offered it to him, to make peace… But he was like that, a brutal guy. Brutal in the sense of “direct.”

Frank?

Direct. He made a direct cinema and he himself was direct as well. I went to two or three lessons, in the beginning, where he “dismissed” three or four students mercilessly, with regard to a paper or a composition about a film. ‘I believe this is not your thing.’ And it was like that. No other teacher would do it that way—they would apply the 3 or the 4, or the 0 [values]. Reis didn’t have that “elegance,” he had another one. He was an aristocrat, a farmer, with that elegance that not even João Miguel had. João Miguel is a poet, with that pleasure of finding the rightest and the most secret word; for Reis it was as if there wasn’t any secret. He was, again, direct, such as I’ve never met anyone else. He reached very quickly, with his discourse, the essence of a film, of an image, a sound, a person. I remember he had analyzed the way I was dressed (all in black, of course). He had a lot of affection for that youthful brightness that leads people to dress the way they think they have to, or to say short but powerful things. It’s not necessary to write hundreds of pages to say what is truly important. All the books he recommended were minuscule works, like Pedro Páramo [by Juan Rulfo] or little texts by Blanchot, by Cioran… What I learned with him was the effort of remaining silent and only saying “yes” or “no,” that is, to be convinced of the things one loves.

Anyways, more than João Miguel [Fernandes Jorge] or João Bénard [da Costa] (who was much more of a professor, in the academic sense of the word, although he was sometimes considered a friend), Reis was truly the giant. “Giant” was the expression he used, when he told us, autodidact as he was, about when he had met two or three people that he referred to in that way: Rivette, whom he considered the best critic and theorist of cinema, or Straub, or Jean Rouch (people he knew well), or Tati, or João dos Santos… According to him, it’s necessary to “ride on the shoulders” of giants during a certain period of time. And I had the feeling that I had to make the most of it. Instead of continuing to behave smart-alecky and insolent, of being defensive or attacking, with Reis I had to listen. I think I recognized something in him and I think he must have recognized something in me, creating complicity between both of us. With many others as well, during the years: we were the chosen ones. Indeed (and I think that anyone you speak about the School with will confirm this) there was something of “choice,” of proximity, that translated in crossing some borders, like going to his house. I think I crossed some.

So, I never missed any of his lessons, because he was also a constant professor. He loved the Film School, because he loved to teach and talk to us. But not only about cinema, from one shot he would go to other journeys, cave art, India… He wrote very little, and he did it, I think, in the sense of only having to “write the minimum.”

Perhaps that’s why our “encounter” happened, in the sense that I entered the School with very straight and select ideas, according to which cinema has to have limits. For me those were: not use special effects, avoid gay cinema, be interested in very violent things. Without these limits, if I don’t think this way, I’m lost. From them, I start to work. And António Reis would agree with me, he would say: “That’s the way you have to do it: continue, I’m here to help you.” He opened some doors for me, some of them unconsciously, others that I didn’t even know existed because I hadn’t found them, at school, in the books I read or in the movies I watched. It was somewhat a vague encounter, but there was, in fact, an encounter of violences. Reis had a tender violence and a strong fragility, always balanced between something very strong and something very sweet. I think I myself also had, in some way, this “violence,” since the fact of being against everything, but doing well that which has to be done, ends up in something sincere, genuine.

What subject did Reis teach?

This is dramatic… (laughs). I think it was Filmic Space…

But how was it? Was there a specific program? A series of films to watch? What type of work did you develop?

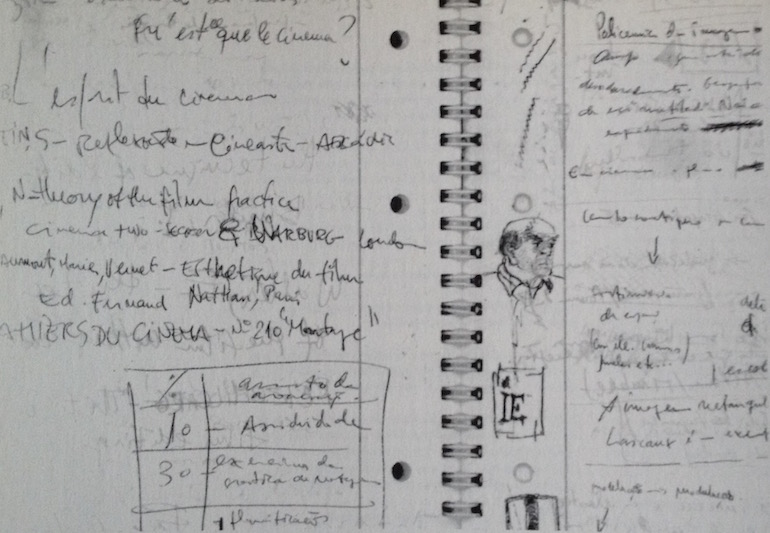

Although it was some time ago, I remember a small A4 sheet of paper with four dots that materialized the program, which he organized in an outline, and then we followed it. We wrote papers, as well as a continuous work during lessons which consisted, for example, in watching a movie “in progress” at an editing table and talking about it, not like the classic “oral tests” but by means of oral participation, informally. Informally because there could be students coming in and out in the middle of the lesson, although without a hustle and bustle. With no other teacher, besides, did we learn self-discipline. In our feelings, in our passions, in our knowledge. On another hand, there was, yes, a series of films. I don’t know if you know, but him and Margarida [Cordeiro] had a list of 10 or 20 essential films, and it was around them that the lessons went.

Do you remember any of them?

I remember almost all of them! I’m not sure if we watched all of the ones on the list, but I remember two or three by Rossellini —Journey to Italy (Viaggio in Italia, 1954), Stromboli (1950)—, especially the latter because there was a copy at the School. I remember one time I was in charge of putting the reel on the table and I let it fall, like a streamer… And my punishment was to roll it all up again… And there also was The General Line (Staroye i novoye, 1929) by Eisenstein, which we watched many times because there was a copy at the School. We went to see a few at the IPC, including Faust (Faust: Eine deutsche Volkssage, 1926) by Murnau, which motivated one of the best “speeches” that I heard by Reis, very inspired that morning. On another hand, my memory of Reis is always set in the morning, although our lessons were in the afternoon. Something of a “beginning”, of freshness, of great lightness like the air.

But coming back to the films, there was The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) by Welles—a film that he really liked—, Marnie (1964) by Hitchcock—a director who he also really liked—, Breathless (À bout de souffle, 1960) by Godard—although he preferred Pierrot le Fou (Jean-Luc Godard, 1956) but there wasn’t a copy at the School—. In any case, I remember this one well because, even if I hate writing and even more about films, he liked the paper I wrote. And there was Bresson, of course; Bresson most of all. Whenever they played his films at the Cinemateca he would send us to watch them. Besides the fact that we all had to buy (and since they didn’t have it in Portugal, it was one of our friends with foreign contacts who ordered it for us) the Notes on the Cinematographer by that Bresson. A kind of “commandments”—“Think this way,” “Do it this way,” “Watch that,” similar, in a way, to the guidance that Reis always gave us from his immense culture—‘You must go see Velázquez in the Prado and only after you must buy the book,’ ‘You must go to the Lascaux Caves,’ ‘If you have money you must go to Persia or Iran to see the rug motifs.’ ‘Save up money to travel, and go alone.’

But coming back to the films, there was The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) by Welles—a film that he really liked—, Marnie (1964) by Hitchcock—a director who he also really liked—, Breathless (À bout de souffle, 1960) by Godard—although he preferred Pierrot le Fou (Jean-Luc Godard, 1956) but there wasn’t a copy at the School—. In any case, I remember this one well because, even if I hate writing and even more about films, he liked the paper I wrote. And there was Bresson, of course; Bresson most of all. Whenever they played his films at the Cinemateca he would send us to watch them. Besides the fact that we all had to buy (and since they didn’t have it in Portugal, it was one of our friends with foreign contacts who ordered it for us) the Notes on the Cinematographer by that Bresson. A kind of “commandments”—“Think this way,” “Do it this way,” “Watch that,” similar, in a way, to the guidance that Reis always gave us from his immense culture—‘You must go see Velázquez in the Prado and only after you must buy the book,’ ‘You must go to the Lascaux Caves,’ ‘If you have money you must go to Persia or Iran to see the rug motifs.’ ‘Save up money to travel, and go alone.’

But do you think these films that you have spoken about were a list chosen objectively to serve specific didactic purposes or did they obey the subjectivity of being, actually, films of Reis's life?

Yes, of course, the second hypothesis.

And did you speak about their work [Reis’s and Cordeiro’s] although in another context?

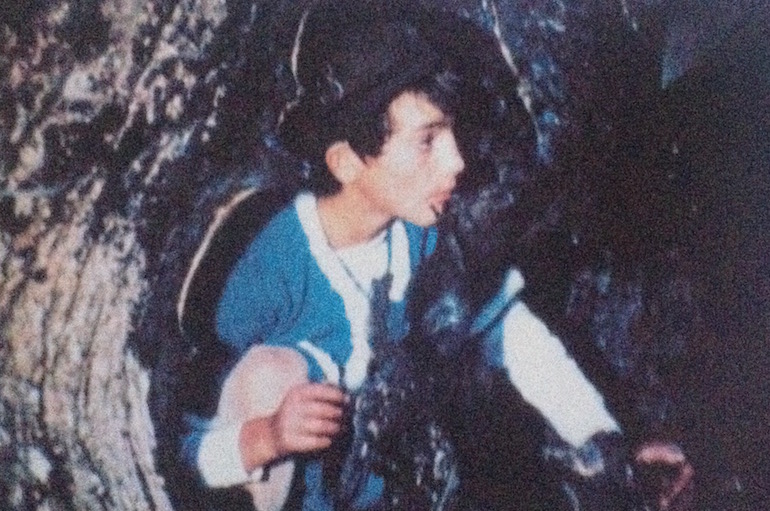

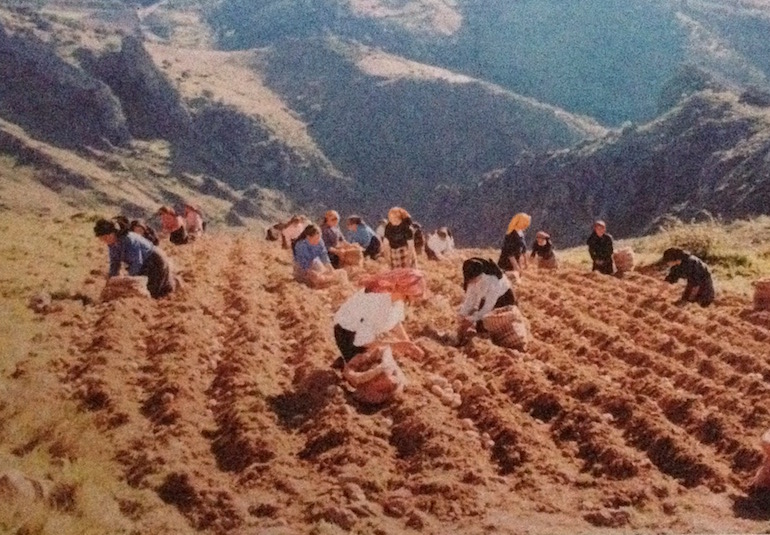

Not specifically about the films. I know that my friends and I, right when we met him, realized that we had to quickly watch Trás-os-Montes (1976) and after Ana (1982). Jaime (1974) was more difficult to access. But it was evident that after meeting the man we had to know his work. This is what was important. Because, for me, from the moment I watched Trás-os-Montes, it was finally the opportunity of starting to have a past in Portuguese cinema. It was finding the poetic reason that I had been pursuing with punk, something like “there’s nothing before and the future doesn’t exist, therefore, we have to do it now”, and I ended up recognizing it in someone who was saying exactly the same things but in films that already existed and which were magnificent. On one hand it was, thus, comforting; on the other, it was being able to establish, as I said before, a type of past, of family, of identity, that gave me security. Not only with Reis but also with Paulo Rocha, at least with his films that I like the most, Os Verdes Anos and Mudar de Vida (1966). So, I wasn’t starting from scratch anymore and even more in a horrible decade as the 80s were, in which cinema had been subject to all types of “epitaphs” with Godard or the death of narrative and fiction.

Reis was very comforting, he gave us essential messages: ‘You have to be careful, learn to hear and listen, but don’t be afraid of filming what surrounds you. If it’s cars, it’s cars; if it’s rocks, it’s rocks.’ We discussed politics every day, we rejected the “intellectual muck” of the turn of the century avant-garde such as surrealism, but we never dropped down to what was real, to what has to be seen and heard, to the patience of seeing and hearing. Now, when we watched Trás-os-Montes—and we had already sensed it in the lessons—, we perceived its documentary side. It gave me more security, because it provoked—and continues provoking more each time— that, when I start thinking about a film, I start first by thinking about someone, real, a face, a way of walking, a place, more than a story. And this is what he proclaimed: ‘Look at the rock, the story will come later, and if there isn’t a story it’s not important.’

But would you say that it’s an “attention to reality” or an “obedience to reality”?

“Obedience” is a word that I don’t really like, and Reis didn’t like it either. Self-discipline, as I said before, yes, because it’s something with a vaguely eastern side to it (which was very profound in him), about detail, about the pleasure of obsessive control over the different shades of everything, from the first word to the last second of the film. An extremely rigorous discipline. The word “rigor” comes to mind in this link with reality, a rigor that with Reis was human, contrary to the majority of those which, like zombies with books under their arm —very visible—, walked around the School. Of all of them he was the only filmmaker who lived and did things. For example, he knew the name of every plant, of every type of rock; he knew what the Príncipe Real neighborhood is made of underneath; he spent hours talking about that cedar [signaling the immense cedar in the garden]; he read a bunch of books about Natural Science or History; but everything always had an application.

He was someone who didn’t mind teaching his lessons, cooking a family lunch, taking a nap, going for a walk and talking with two or three friends, drinking his “espressos” (all the coffees he always paid for, he must have paid for hundreds of espressos here or in “Júlia”, which was a café in front of the School, since he had four or five with each student…).

To summarize, Reis is the person who said in words and in films that which I thought and didn’t know how to express. I knew what I liked but didn’t know why I liked it. And Reis explained it to me. ‘You like this because it was in a painting before, and that painting has to do with a certain social organization of that time, and the things are things because at the same time they are the life of men transformed into art in that same time.’ Time, space, the topics of his discipline.

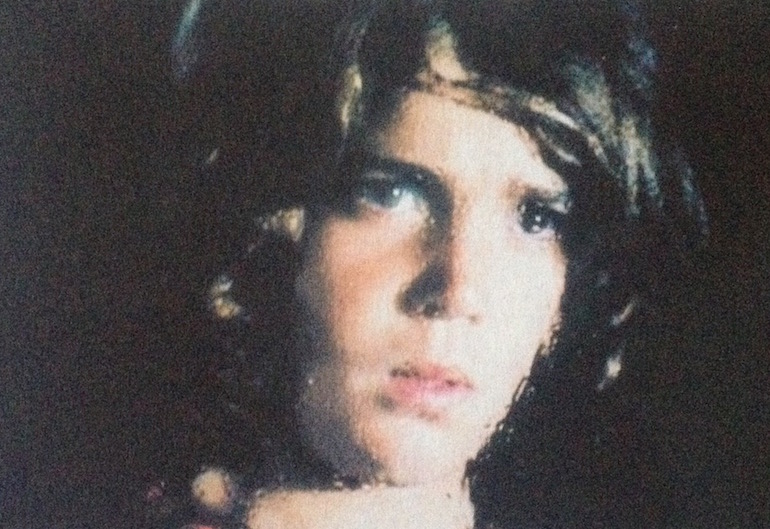

Below: Ana (António Reis and Margarida Cordeiro, 1982)

I would like you to, nonetheless, explain to me in more depth what Reis’s analysis was, during lessons, of the films you watched. I’ve already deduced that he wasn’t interested in the story. But how did he analyze the shots? Each one independently? Detecting influences and relations in one shot…?

Exactly as I said before, the story is in the shot. And after a shot there’s another shot, and what happens between these two shots is what’s important. Here is where everything is in stake, between these two shots. And it was most of all with Reis that I learned this, although afterwards I have delved into it with books by authors such as [Serge] Daney, [Jean-Louis] Schefer, [Jacques] Rivette, [Jean-Marie] Straub… This is what is useful to me nowadays, that which is between shots: that which you say, that which you leave, that which you filmed and that which you didn’t film, what is or what isn’t between those two shots: the raccord. Cinema, for him and Margarida, and for me, is the raccord. It’s not even the shot. I mean, the shot is the unity, it gives us the story, big or small, it gives us the gaze, your distance on things, what you choose, your field, but, above all this, when we decide that the shot finishes it can be exactly when it starts. This is the difficulty: the decision of extending it or finishing it, that is to say, the cut. The cut between images is what counts. That’s where your being is at stake. Reis was very much an author (Reis and Margarida, of course; I speak of Reis as a professor, but whenever I speak about him as a filmmaker I am also referring to Margarida), and an author is a strong person; but in spite of everything, he said—or at least he made it understood—that that moment, the raccord, is the only moment in which one can be diluted, as a being, with matter.

“Dilute” in the sense of “merge”?

Exactly. In the link between shots you can merge with the characters (if there are any) or the things (the objects, the houses, the rocks, the clouds), you can hide, that is, become better integrated. (…) Personally I live the “filming” of a film in the sense that the whole film is something done with a minimal intervention from my part. (…) More and more, my films get closer to the almost pure documentary or its absolute contrary, in which I carry out a reorganization of reality that I have come to with a great abstract perspective. I prefer to discover the stories as I film.

And that is Reis?

I don’t know, because I never went to film with him. I know, though, that they went very prepared, they knew the exact time the sun set in a certain place, the color of the clothes, the word that Mother Ana had to say in that scene… I’d say that they knew the exact time of the shots down to the second. But which was the part of the “unexpected” that they let into the filming I do not know, and I’ve never known. I know some production stories, about things that weren’t able to be done in a certain way and were done in another one which they had found better. But I’m sure that they relied a lot on preparation and study. There was quite some time between his movies, although I know of one or two projects that they would have liked to film quicker, especially one, which we spoke about many times and which we almost started to write together, set in Lisbon, in black and white, about punks. His films “worked” very well in Berlin, and he always came back very moved, with tears in his eyes, because, in the punk capital of those times, the theaters would fill up with 15 and 16-year-old kids with green hair—those “green-haired princes with leather jackets that cried when watching Trás-os-Montes and afterwards went to play the electric guitar”, as he described it. He loved this phenomenon, the mixture between sweetness and violence, because he himself was like this: affection and brutality, without measure. Very affectionately, he would touch people amicably, but without measuring his strength, so certain “smacks” were actually very hard… (laughing).

Maybe it consisted of an almost instinctive strength, perhaps the same strength that made him sense, in class, who the promising students were?

In Reis (as in many other people) there was that kind of acknowledgement, or that acknowledgement could be produced, without being in the sentimental field of love. That recognition is very strong, very intense, because there’s something of dependency. All those who liked Reis were very dependent of him, and he was, at the same time, very dependent of some of our aspects—our youth, our knowledge of music… For example, the song lyrics like the ones from The Clash had a lot in common with his poetry, that is, the everyday poetry. It was beautiful. Very dependent people, very strong and very weak, who don’t need anyone and need everything, who are always alone. Reis was always alone. Immensely solitary.

Except with his family, I guess…

Of course, but I don’t think it would surprise Margarida to hear me say this, because Reis had always been alone, just like she had always been alone as well, in the sense that the solitary person has their own world. And he was solitary. Probably that’s why he recognized other solitudes in the students he had.

Would this be one of the reasons why their filmography is so unique, so particular?

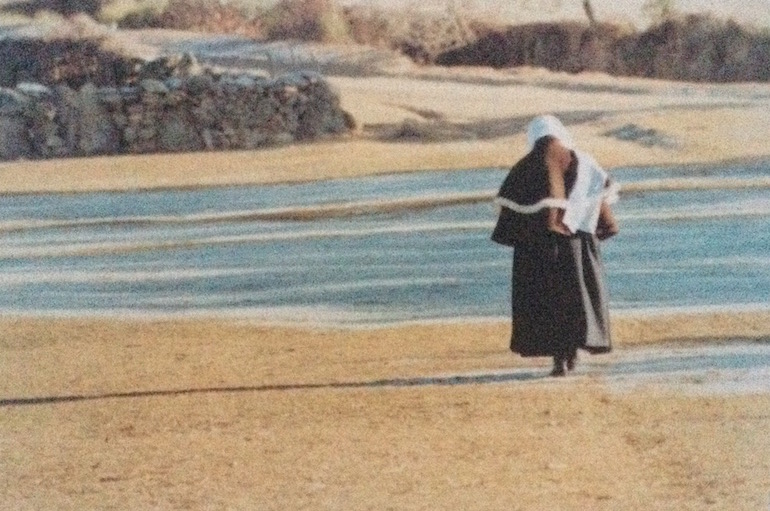

Yes, but I don’t want to say it was better or worse, or more singular, than Paulo’s [Rocha] or [Manoel de] Oliveira’s. What touches me more in theirs is something that I don’t know how to explain and I don’t have words to define, and that I don’t find in other films. For example, the other day I rewatched Francisca [by Manoel de Oliveira], which I think is absolutely genius. I had seen it when it was released (1981) and, in addition, by António’s recommendation. Let’s face it, Manoel de Oliveira wasn’t a filmmaker of Reis’s choosing, although he respected him, had been his assistant and liked some of his films a great deal—nobody spoke of Amor de Perdiçao (1979) like him—. But it was partly because of Reis that I went to watch it, and perhaps that’s why I perceived it in a totally different way than how I did recently. Of course time has passed, the way we access films has to do with each person’s history, I’ve had more experiences… But there’s something in Reis that I don’t find in Rocha or in Oliveira (and I mention these two because, with him, they are the three best Portuguese filmmakers), that has to do with… a type of photogenic quality. Don’t ask me to specify because I can’t say more than… there’s something in the faces, in the people, not so much in the bodies but in the skins, in the rugosity… a photogenic quality “without” aesthetics, that is captured directly and very well, that is, taken instinctively, as if it were bitten… something very, very sensual. To summarize, in Reis there is an almost animistic sensuality that I don’t “have” in Paulo or Manoel; there’s a sensuality, not savage (although he spoke a lot about savage beings), but delicate and beyond words that can only really be captured with cinema. Why? Because there’s a sensual side to it, of the senses, that can, actually, be animated by cinema, that is, one can film something and then animate it with a different type of life, a life that is not life.

This pleasure, this dimension that I don’t dare call “sexual”, is to me masculine, grave (in the sense of “serious”). There’s something seriously masculine, in Reis, that Paulo doesn’t have, because he is a very feminine filmmaker, and Manoel either, because he is excessively macho. Reis, on the contrary, is everything…

In human terms, I had the impression (that this conversation only confirms) that Reis was really someone very honest, right?

Yes, yes. It’s really very implicit in everything he said. I’m not his age yet, but I think I have to start saying that cinema today, in Portugal, is very miserable. And it could have been another way. And the lack of Reis is immense, even because what he said, he said it directly. ‘This movie is very bad,’ ‘This person shouldn’t film for now,’ ‘Don’t give money to this person,’ ‘Give money to first works’, statements that no one says nowadays. We live in a paralysis, this type of “everyday pornography”, which has started to lack beauty and a sense of dignity. And Reis had a great deal of dignity. He said upfront and quickly what had to be said. Now we do press conferences to announce the films that will be done, and we only think about what will make the most money… People are aging badly, very, very badly. And António Reis was young, he was never old… he was ageless.

That’s why he kept his first beliefs, those that are really liked without knowing why. Try speaking, writing or drawing, but what is true is that it’s yours; it’s your better, a part of you. If you look at something and it looks at you back, it’s because there is a part of you there. And this is what Reis told us, that we had to choose early a field of action, of combat, of work. And Reis chose. He chose the field of the humble (don’t take it as a pretense, because that’s not the attitude), that is, a certain humbleness of the people, of the feelings, of the little stories and the little gestures, that really belong to a singular class. And if you study well and stand by him, that class will give you class; he wouldn’t say “style” but “elegance”. Reis was very elegant. On a day-to-day basis, he would give you money if you needed it, he would feed you, teach you, ask you, this exchange elegance that turns aristocrat because it doesn’t have commerce. That’s where the brutality comes from. And the elegance. And the great humbleness.

Reis chose from an early age the autodidact path, a life without pageantry, of small rooms in Oporto, of small jobs, of that “dry” poetry about nighttime or how hard it is to wake up in the wee hours of the morning, that is, a path anchored in a humble life, almost thrifty. This choice of the field of the humble was for me essential, as there is, in the poor, a beauty, a richness, a truth, that is getting lost because it’s frowned upon, and can only be obtained when spending a great amount of time with these people. Reis spent his whole life with them. This idea of humbleness, which, I insist, is not pretentious, is a good choice because it draws limits. He and Margarida liked this. And I do, too: there’s lines that cannot be crossed, licenses that can’t be taken, borders that shouldn’t be trespassed, because cinema starts one way and it will end—if it ends—in the same way.

That is…?

Like the poor. Cinema started looking at people who did not have an image, it didn’t start by making stories: it’s History. And that is, for me, what is magnificent. For example, this film that I have just finished —Ossos (1997)—, is unique because there has never been anything like it and there will never be anything like it. There’s a capture of something, but nothing to invent. I felt this resistance to invention in António and I think he had gotten it from Rossellini. Why invent? Only idiots invent in the basis of a cinema that has already been seen, of what’s general, universal, of the majority. Now, good movies don’t have to invent anything, they only have to watch and reproduce. But reproduce in a different order. In this sense, all of Reis and Margarida’s films are “supernatural”, because they are ordered in an order that has never been seen and that isn’t the first one. And you, when you go, will also make your own order.

This interview, which took place on July 28th in Lisbon, by Anabela Moutinho and Maria da Graça Lobo, was published in the book: MOUTINHO, Anabela y DA GRAÇA, Lobo (1997). António Reis e Margarida Cordeiro. A poesia da terra. Faro: Cineclub de Faro. We thank Pedro Costa, Anabela Moutinho and Maria da Graça the authorization to reproduce and translate this article.

Nº 6 THE POETRY OF THE EARTH. PORTUGUESE CINEMA: RITE OF SPRING

Editorial. The poetry of the earth

Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

The soul cannot think without a picture

João Bénard da Costa, Manoel de Oliveira

A certain tendency in Portuguese cinema

Alberto Seixas Santos

To Manoel de Oliveira

Luis Miguel Cintra

The direct experience. Between Northern cinema and Japan

Paulo Rocha

Conversation with Pedro Costa. The encounter with António Reis

Anabela Moutinho, Maria da Graça Lobo

ARTICLES

The theatre in Manoel de Oliveira's cinema

Luis Miguel Cintra

An eternal modernity

Alfonso Crespo

Scenes from the class struggle in Portugal

Jaime Pena

Aesthetic Tendencies in Contemporary Portuguese Cinema

Horacio Muñoz Fernández, Iván Villarmea Álvarez

Susana de Sousa Dias and the ghosts of the Portuguese dictatorship

Mariana Souto

REVIEWS

MARTÍNEZ MUÑOZ, Pau. Mateo Santos. Cine y anarquismo. República, guerra y exilio mexicano

Alejandro Montiel