TEN FOUNDING FILMMAKERS OF SERIAL TELEVISION

Jordi Balló and Xavier Pérez

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / ABOUT THE AUTHORS

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Hitchcock: the control of the audience

1955 is a key year for the history of television fiction: Alfred Hitchcock decides to occupy the universe of seriality with a weekly production that carries out his name in the title (Alfred Hitchcock Presents, CBS-NBC, 1955-1965) and that includes, at the beginning of each chapter, an introduction with the filmmaker addressing his audience directly. This corporal signature, already present in the form of cameo appearances since his first films, found an exceptional reaffirmation space on the weekly television recurrence. From being functionally known by the audience, Hitchcock (as a brand-image, enhanced by the complementary profile’s caricature heading the credits, and by the accompaniment of Charles Gounod’s catchy march) turns out to be an undeniable popular icon. The hidden objective is to use the small screen as a platform to radicalize one of the central strategies of Hitchcockian art: the control of the audience. Through the serial recurrence, Hitchcock could experiment, each week, the hypnosis persistence through the visible signature of the dominant Wizard.

Hitchcockian control of seriality comes from repeating as many times as necessary the same model of narration. Twenty minutes of maximum narrative concentration which insists on, with only a few changes and a recurring final twist, recreating all the possible shapes of a nightmare. There is a logical explanation (never supernatural), but the model of the narration takes into account the structural teachings of Poe, often invoked in plot motifs such as the perfect crime, the double, the revenge, the psychological madness or the premature burial.

The serial pattern is determined not only by the initial appearance of the Wizard, but also by the final salute which summons the following week: a subtle variation of to be continued that substitutes the prolongation of the tale ad infinitum with the circular persistence of the unavoidable serial device. Hitchcock founds a decisive strategy, later implemented by Rod Serling in The Twilight Zone (CBS, 1959-1964), which will constitute the first model of permanence of the author –and the control of his/her universe– within the framework of television-making.

Rossellini: the encyclopedic dimension

The first intervention of Rossellini in television with the series L’India vista da Rossellini (RAI, 1959) does not spare the presence of the director in the opening of each chapter. But if Hitchcock threw himself in a self-sufficient way to reach the viewer, Rossellini is introduced by the journalist Marco Cesarini, and the vision’s prelude turns into a dialogue that has a continuation when showing this carnet de notes of his voyage to India. Over the images projected in the small cinema where Rossellini and his interviewer sit, an off-screen dialogue takes place that contributes to a clarification, more impressionistic than dogmatic, of the takes’ content. This revolutionary format will be no longer present in the next one, L’età del ferro (RAI, 1965), where the presentation is done with the talking head of Rossellini addressing the viewer –but the television corpus of this filmmaker will not renounce to a democratizing, horizontal key.

History being a susceptible discipline to audiovisual recapitulation will constitute the thematic core idea to test the efficacy of the serial device. In L’età del ferro, the whole is framed to the technological evolution of humanity in regards to the production and use of iron through the centuries. In La lotta dell’uomo per la sua sopravvivenza (RAI, 1970) he proceeds to reconstruct the evolution of humanity, where every progress milestone makes a difference and a step from one episode to another. The overall television fictions based on Louis XIV, Socrates, Descartes, Augustine of Hippo, Blaise Pascal and the series Atti degli apostoli (RAI, 1969) and L’età di Cosimo de Medici (RAI, 1973) are examples of this encyclopedic will, sustained by a didactic method: the broad range of each historical setting invites to concentrate on the detail and on the scrupulous slowness of the tracking. Rossellini inverts the idea of the Hitchcockian control of the universe to trust in a spectator endowed with the right to be culturally nourished through a new technology understood, against all contextual odds, as a formative tool in the service of humanism.

Wiseman: the exhaustive project

Frederick Wiseman’s documentary films, if strung together, could by understood as elements of a single work, a serial work as a big human comedy. His objective is to question and portray, one by one, every US public institution and also some in Europe, showing their weaknesses but also their surviving capacity in difficult environments. This systematic work began with Titicut Follies (1967), where he entered a prison/asylum/hospital with unacceptable clinical practices, including prisoners’ lobotomies, displayed in all their crudity in front of the camera. The result of this revealing work was its banning by the Massachusetts State for 30 years. At the time the PBS was able to release it, it already had become an American legend of independence.

Wiseman’s works have gone through the State’s structures and their effects: prisons (Titicut Follies), schools (High School, 1968), police stations (Law and Order, 1969), hospitals (Hospital, 1970; y Near Death, 1989), military academies (Basic Training, 1971), courts (Juvenile Court, 1973), animal experimentation labs (Primate, 1974), social assistance (Welfare, 1975), theatres (La Comédie Française, 1996), public housings (Public Housing, 1997), domestic violence (Domestic violence, 2001; y Domestic Violence 2, 2002), state universities (At Berkeley, 2013), museums (National Gallery, 2014) or neighbourhoods (Belfast, Maine, 1999; In Jackson Heights, 2015). On Wiseman’s filmmaking methodology, sound takes on a decisive significance, as it is the word, the shout or the silent gesture what eventually indicates the preponderance of what deserves to be filmed within a sequence. This issue explains the constructive character of his sense of editing, the relation between on and off-screen spaces that leads the way of his filming style and builds a direct cinema but only apparently.

But Wiseman’s greatest influence in the world of seriality is the exhaustive conscience. David Simon also used this method in The Wire (HBO, 2002-2008), where each season addresses one conflict zone: police station, port, union, school, political elections, media... The resulting serial work establishes a network that achieves its maximum intensity when it considers society in its totality. It is the construction of a pointillist portrait of democracy’s imperfect instruments.

Ingmar Bergman: dialogues in time

The serial nature of Ingmar Bergman's audiovisual production, well established in his filmography since the so-called “Trilogy of Faith”, takes a transparent significance in the television production Scenes From a Marriage (Scener ur ett äktenskap, TV2 Sverige, 1972). In several countries this material was released in the form of a feature film, an issue perfectly accepted by the filmmaker, who re-cut the material to create a forceful autonomous film. However, the cadence of these periodical marriage dialogues goes especially well with the television format, doubtlessly.

Bergman, a man of vast and complementary theatrical career, based his film work on the essentialist record of the word, with the close-up as the privileged device of expressive confirmation. And this word that becomes time finds in the television format an ideal space for the experimentation on perseverance and for the enjoyment (sweet and sour, given the drift of this plot) of repetition. The crisis of this couple, but also their continuous reaffirmation, the game of secrets and lies, the reproaches and forgiveness, the satisfactions and the withdrawals, get tangled up in a string of highly significant intimate moments which turn the television screen in a minimalistic laboratory for the observation of the human being in the ambivalent experience of domestic confrontation. The masks of a happy everydayness, so typical of classic television, are contrasted with their dark mirror image by Ingmar Bergman's exploratory eye.

The fact that the main characters of Scenes of a Marriage found some extension in different theatre adaptations and especially in the film Saraband (2003), its epilogue, confirms this serial model capacity of spreading in time and space with a canonic shape open to new variations. And the foundational weight of this episodic micro-dramaturgy can be seen as a deposit in contemporary works such as the different versions of Be Tipul (HOT3, 2005-2008), and other series like Mad Men (AMC, 2007-2015) or Masters of Sex (Showtime, 2013-), which turn the confronting word and the confession that finally emerges into a unyielding therapeutic exercise.

Jean-Luc Godard: the device revealed

Six fois deux (France 3, 1976) and France/tour/detour/deux/enfants (Antenne 2, 1977), the two television programs directed by Godard in his decade of retirement from conventional exhibition and the investigation of new video-graphics territories, are two peculiar enquiries around the 70’s French society. Godard picks up Rossellini’s hypothesis of television as an educational project, and focuses the interest on the function of the interview as serial pattern. The inquiry is, however, restrictive, reduced to a few characters and in a constant dialectic process with the interventionist presence of Godard himself. In the extreme and polemic case of France/tour/detour..., the interviewees are only a boy and a girl, sitting down, and driven by the director in a persisting, almost totalitarian way.

The operations that have to accompany the inquiry’s constitution are identified by the evidence of the device, and by its derived critical detachment. For example, on each interview of Six fois deux’s first chapter, Godard, badly framed at the left of the shot, in front of the table where he receives his interviewees, only lets us see his arm and the cigar going from the mouth to the ashtray, with a repetitive gesture that will pass through as a permanent recognition icon of the author in all his future work.

Six fois deux’s other sign of serial identity is the opening title with a hand entering a video-cassette in a player, and the final image of the same hand bringing it out. Video’s new possibilities create a new field of experimentation where images turn back and became reversible. Editing’s discontinuity (accentuated by rewinds, imperfections, random jumps) becomes, paradoxically, a new sign of identity of serial continuity. And it is here where Godard starts an idea that will be fully developed in his monumental Histoire(s) du cinéma (France 3, Canal +, ARTE, La Sept, TSR, 1988-1998): repetition and persistence of images and sounds, reminiscences based on a subtle variation, due to an omnipresent demiurge who, through the visible manipulation of the materials, continues to make evident, through the symphonic fragments’ gathering, his boundless and incisive signature.

Fassbinder: heterogeneous intensity

When R.W Fassbinder approached, in 1980, the adaptation of the novel Berlin Alexanderplatz, he immediately understood he could not do it in a normal feature film’s temporality. The influence that Döblin’s novel had had in his formation years pushed him to conceive this project as a titanic, absorbing work on which converges, already present on the original book, the shape of a visual and sound collage which was one of the director’s main characteristics. It thus has been this way that he imagined an episodic proposal of 13 chapters and an epilogue, a unique work on which he builds the portrait of a city in the process of decomposing itself, where the sense of exploitation, violence, survival instinct, are expressed through a composition which combines baroque choreography with distancing techniques and behavioral analysis. Fassbinder saved for himself the narrator voice as the gesture of a presence that wants to understand, or analyze coldly, the attitude of his characters, the secrets of their desire and their passions. Fassbinder’s empathy with the main character, Franz Biberkopf, his relationship with Reinhold, and with the women who love him but ended up being destroyed by him, makes more interesting the way in which his own implication is produced through voice, style and shooting speed.

Both Julia Lorenz, editor, and Xaver Schwarzenberger, DP, explained a revelatory detail: if Fassbinder did rehearse the scenes with his usual actors, he used to film almost every sequence in only one take. The film combines the caring for the framings with this temporal economy principle, in a manner of registering his usual way of conceiving and making films, with no pause, enchained, like a serial filmmaker.

It is in the epilogue of Berlin Alexanderplatz (WDR, 1980), actually a feature film in his own right, where Fassbinder goes a step forward, a decisive gesture in his freedom of conceiving a series. This apocalyptic, delirious epilogue concentrates the capacity of infernal description, with ambiguous angels, madhouses, rats, religious imagery, contradictory recuperation of previous plots and, very especially, with a mise-en-scène of the torture, with the dismembered bodies of Biberkopf, his partner Mieze, and other groups of young people piled on the floor, in a crystal clear reference to the film which shocked Fassbinder the most, Saló (Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma, 1975) by Pasolini, a referent in the way of broadening Evil’s imagery. The epilogue of Berlin Alexanderplatz was a precursor of a category in contemporary seriality: a narration can present chapters with completely different styles thus making scenarios of exception.

Reitz: the dynasty

One of the essential points which united the signers of the Oberhausen Manifesto was the fact of not feeling implicated or able to be held responsible by previous conventional cinema; the will to talk about Germany’s current situation with a new language. But paradoxically, one of its signers, Edgar Reitz, centered his filmography on a single work which reviews past, understood as a public position of his mission as a filmmaker. This work that doesn’t cease to grow, Heimat (1984-), started as a kind of sinuous feature film that needs to be divided in chapters in order to arrive to the audience. Most part of the filmmakers making television do not question the episodic system, but the case of Heimat is quite the contrary: it makes profit of the device of television segmentation in order to make possible the production of a complete work which overflows the logic of cinematographic exhibition.

The dramatic core of this expansion is family unity, and geographical location: the Simon family history, located in an imaginary place in Germany. But differently from paradisiacal seriality based on the dynasty tale, which used to hide or resolve conflicts on each episode, Heimat outlines the history flow as a succession of fractures, dilemmas, tragedies and mutations, through two World Wars and the different economic and social crisis. The idea that the collective crisis acts as the accelerator and trigger of the drama proposes a serial logic based in the appearances and disappearances of drama, with a rhythmic dynamism that connects the evolution of the saga with the historical, temporal and critical view of the spectator.

The epic dimension of Reitz’s project is viewed as a great victory of experimental cinema. His logic is not that of family soap opera: in Heimat the force of the ellipsis imposes itself in front of the series based on the dramatized everyday. But its point of view is also experimental, confronting private history localized in a microcosm with the events that may happen off-screen, reconstructed by the viewer, as a real national tragedy. German homeland’s life is not centered solely in the things Reitz is showing, but also in the citizen’s responsibility facing some aspects of its hiding. It is because of all this that Heimat, which has produced in 2015 a feature film proposing a prequel to the family history, becomes a milestone in the way of showing that the dynasty genre is a serial device which cinema can adopt when it creates complicity with the strategies of a public television.

Kieslowski: a vertical succession

We often understand seriality as a sequence of episodes bound horizontally with a temporal continuity. The most unique contribution in Dekalog (1989-1990) is its vertically structured conception, as a building –a fiction architecture in which each episode is put on top of the prior, intertwined, establishing a fertile relation between variable elements and repetitions. Dekalog’s co-writer, Krzysztof Piesiewicz, expressed it indirectly, declaring to have been inspired by the Gothic retable in the conception of the continuity of each episode: the Ten Commandments, told independently, each one with a particularity, looking for a contemporary inversion of a general prohibition questioned in each of the works. The elements of repetition are light, but firm: Zbigniew Preisner’s music, the fact that all the characters live in the same building in Warshaw, the recurrence of a quiet, observant character who appears mysteriously in almost every episode, and some operations of intertwining characters who can be the protagonists of one episode and mere extras in another one. There is also an exemplary case of meta-fiction when the moral dilemmas of Dekalog 2 are presented as a subject of debate in a philosophy class in Dekalog 8.

This vertical structure allows a non-chronological view of the episodes, because it is not there where his strength can be found, but in the conscience that all of them form an indestructible grid recognized in the general atmosphere of the plots, in this application of the mechanics of suspense in the emotional behaviour.

If each one of the episodes could become an independent feature film –as it happened explicitly in A Short Film About Killing (Krótki film o zabijaniu, 1988) and A Short Film About Love (Krótki film o milosci, 1988), extending the plots in Dekalog 5 and Dekalog 6– what makes Dekalog an essential milestone is having proved that the viewer’s memory and his enjoyment of repetition is nourished by the familiarity of a formal and narrative universe, by the conscience that the crossed glances and the fictions also continue off-screen: while we see a particular history we never lose the general sense involving all the building’s residents and, by extension, the whole community. As in a retable, as in a sort of fiction architecture that continues being one of the ideals of seriality: to progress dramatically in the cumulative mind of the viewer.

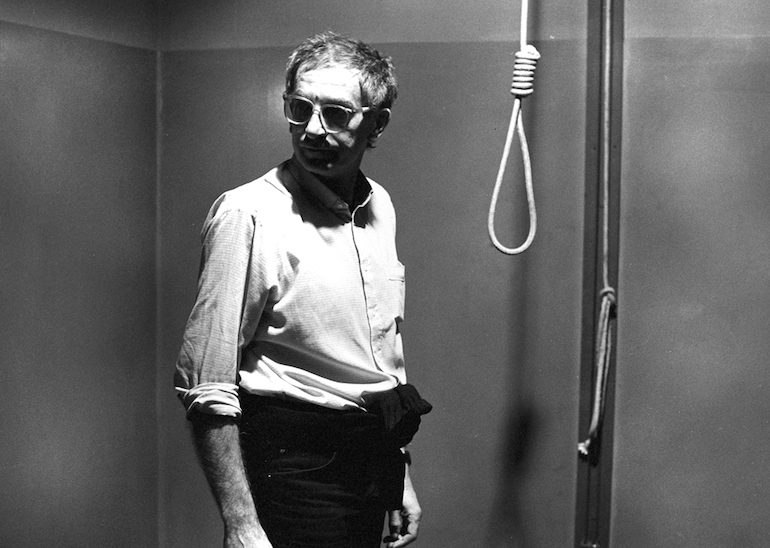

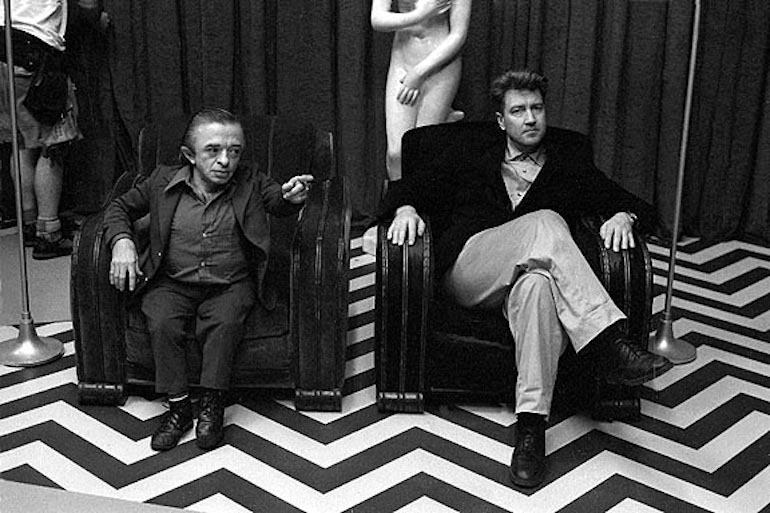

Lynch: the universe in each shot

The so-called “new golden age of television” finds in Twin Peaks (Mark Frost and David Lynch, ABC, 1990-1991) the inescapable foundational gesture. That this revolution presents in its leading role a recognized cinema artist implies, above all, the redemption of the superficial, standard nature of television découpage in most of the previous fictions. Lynch bursts in the cathodic universe to convince us of the oracular value of each image. And, at the same time, to dismantle the idea of the television set as a comfortable piece of furniture in the trivialized interior of the domestic space. If the classical serial fiction had been the paradise of the family gathered in the living room, amazed by the friendly routines of their favorite characters, Lynch violates completely this ritual without surprises and explains us that hell can also take the shape of repetition.

In order to make this possible, the routine of domestic shooting must be hit by an image that manifests itself, orphic, with all its revealing powers. Twin Peaks is shot as if it was a film. The filmmaker transfers the unsettling conception of the shot in his previous feature films to the comfortable spaces of soap opera and, as an apocalypse herald, brings hell behind him. Agent Cooper’s catabasis supposes in this way the vivisection of a community in lethargic state, in need of a perturbing compensation. Laura Palmer body’s autopsy as recorded in the initial episode of the series is the clear narrative of this: a scalpel performing the functions of the editor who splits, analyzes and makes visible.

Lynch’s prophetic proposal seemed, in the moment of its release, a precious pearl in a consumption universe directed towards different interests. Some years later it is clear for everybody that serial fiction does not admit a turning back nor allow suturing the wounds of a destructive time. On the contrary, this time is embodied in a corrosive malignity that takes control over all. This epidemic, constantly expanding, has fed this new millennium’s serial imaginary, where the construction of the cathodic worlds can no longer neglect the performative power of the gaze or the unsettling complexity of each camera position.

Lars von Trier: the immoral space

The Kingdom’s (Riget, DR1, 1994-1997) main contribution was to invert the sense of a dramatic space, the hospital, which in television seriality had been conceived as the paradigm of morality and positive resolution of conflicts. Coinciding in a similar strategy to the one used by Lynch, Riget supposed the emergency of a hellish space as a centripetal unity, a place we can hardly escape, progressively attacked by the symptoms of decadence and destruction. The ghostly voices of the dead, the blood spilled by the air-conditioning tubes, the never-ending corridors, a mason corporative logic and a hierarchical tension between the members of the medical community offer a portrait which tells us that Evil occupies this sick building of Copenhagen.

In a moment of maximum visual experimentation in Lars Von Trier’s career, Riget also supposes a crossing between the veristic devices to capture reality and the introduction of fantastic elements that question it. The fact of maximizing the unit treatment of colour offers the possibility to understand its appeal to seriality for the unity of style. In a certain way it means the incursion of a cinematographic way of shooting in the creation of a unique universe: the repetition is produced by the nature of image itself.

The fact that Lars Von Trier appears in the end of each chapter, discussing the episode and announcing the following, is a reverberation of Hitchcockian seriality, when the director should still notify his presence in a serial world that didn’t seem a filmmaker’s homeland. But this distancing presence of Von Trier, that set out the rules for each chapter and it is no longer essential, does not contradict the greatest contribution of this series: to have been able to draw an evil everydayness in the core of an apparently comfortable society. And to do it through the sick body, the presence of the cadaver understood as the expression of control, as a consumption object, as a metaphor for biopolitics.

Beyond its universal contribution, Riget created a road for the following fertility of Danish seriality: unit of style, darkness, unsettling dead bodies and a sense of corruption impregnating every structure of the State, even those who seemed sheltered from destruction.

ABSTRACT

This article offers an overview of the work of ten founding filmmakers of serial television (Hitchcock, Rossellini, Wiseman, Bergman, Godard, Fassbinder, Reitz, Kieslowski, Lynch and Lars von Trier), juxtaposing their key achievements with other television series that constitute a shared legacy.

KEYWORDS

Cinema, television, serials, audiovisual narratives, Hitchcock, Rossellini, Wiseman, Bergman, Godard, Fassbinder, Reitz, Kieslowski, Lynch, Lars Von Trier

JORDI BALLÓ

Professor of Audiovisual Communication and director of the MA in Creative Documentary at Universitat Pompeu Fabra. He is the author of Imágenes del silencio (Anagrama), Conèixer el cinema and Cinema català (1975-1986) and frequently writes for the newspaper La Vanguardia. He was director of exhibitiones at CCCB and curator of El siglo del cine, Hammershoi y Dreyer, Erice-Kiarostami or Pasolini Roma. He was awarded the Prize Ciutat de Barcelona for the exhibition Todas las cartas. Correspondencias fílmicas. Along with Xavier Pérez, he has written a series of influential essays on cinema and serial narrative published by Anagrama: La semilla inmortal, Yo ya he estado aquí and El mundo, un escenario.

XAVIER PÉREZ

Professor of audiovisual narrative at Universitat Pompeu Fabra and author of the books El tiempo del héroe, El universo de «Los Vengadores», El suspens cinematogràfic and Películas clave del cine de espías. He developed a longstanding career as a theatre and film critic for the newspaper Avui, and more recently, for magazines like Caimán. Cuadernos de Cine or Cultura/s, the cultural revue of La Vanguardia. Along with Jordi Balló, he has written a series of influential essays on cinema and serial narrative published by Anagrama: La semilla inmortal, Yo ya he estado aquí and El mundo, un escenario.

Nº 7 HOW FILMMAKERS THINK TV

Editorial. How Filmmakers Think TV

Manuel Garin and Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

Cinema and television

Roberto Rossellini

Three questions about Six fois deux

Gilles Deleuze

Birth (of the image) of a Nation

Jean-Luc Godard

The viewer’s autonomy

Alexander Kluge

Cinema on television

Marguerite Duras and Serge Daney

Critical films were possible only on (or in collaboration with) television

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Medvedkin and the invention of television

Chris Marker

TV, where are you?

Jean-Louis Comolli

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Between film and television. An interview with Lodge Kerrigan

Gerard Casau and Manuel Garin

ARTICLES

Ten founding filmmakers of serial television

Jordi Balló and Xavier Pérez

Sources of youth. Memories of a past of television fiction

Fran Benavente and Glòria Salvadó

Television series by Sonimage: Audiovisual practices as theoretical inquiry

Carolina Sourdis

The televisual practices of Iván Zulueta The televisual practices of Iván Zulueta

Miguel Fernández Labayen

REVIEWS

JACOBS, Jason and PEACOCK, Steven (eds.). Television Aesthetics and Style

Raquel Crisóstomo

WITT, Michael. Jean-Luc Godard. Cinema Historian

Carolina Sourdis

BRADATAN, Costica and UNGUREANU, Camil (eds.), Religion in Contemporary European Cinema: The Postsecular Constellation

Alexandra Popartan