CINEMA AND TELEVISION

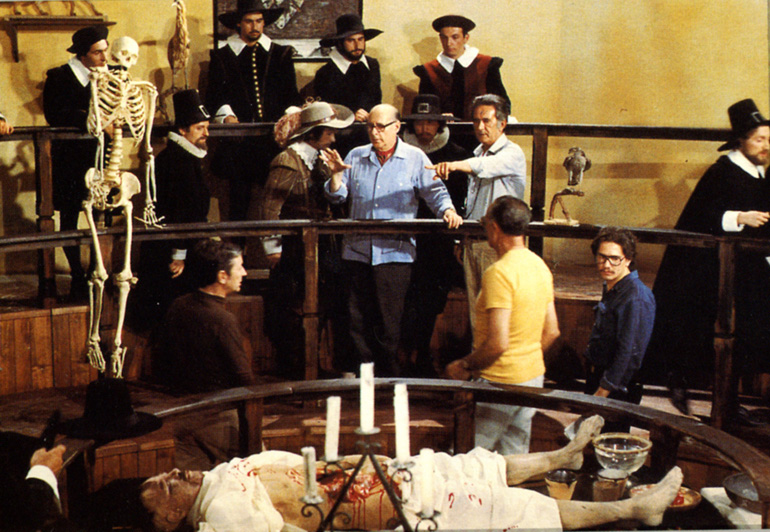

Roberto Rossellini

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

Television is, nowadays, the most powerful and suggestive of this two communication media because it has a greater audience. Television should be, therefore, the most adequate medium to promote integral education; this is to say –according to Antonio Gramsci’s words- ‘a new proletarian Weltanchauung’, a new concept of life and people. Gramsci affirms:

‘One must redo the creation of a new integral culture which would have the popular character of the Protestant Reformation and the French Enlightenment and the classic features of Greek civilization and of the Italian Renaissance. This would be a culture that (to use Carducci’s words) would synthesize Maximillian Robespierre and Immanuel Kant, politics and philosophy, in a dialectical unity inherent not only in a French or German society, but in a European and world-wide one.'

It is not necessary to add that, in the present time, those who control and direct television stations all around the world do not have these concerns. Neither seems to interest them the challenge when studying a new form of education; the idea of achieving an ‘integral culture’ has not crossed their minds. For them, television is nothing but a media to get ‘enjoyment’ and popularity; they use it as propaganda to sell certain goods, and to gain followers to that ideology, to this or that political party, to give or rest importance to certain groups of pressure. The speed of television’s development and consolidation, before its rapid deterioration and its reduction to an advertisement vehicle of a product or an opinion, is obvious. The speed with which it has gotten away from all the concrete truth, the intelligence, and all authentic knowledge, is obvious as well. But the emergence of television has created some other diseases: it has allowed the triumph, acceleration and institutionalisation of the process of corruption of cinema, just in the moment when more important concerns, other than enjoyment or entertainment, were being aroused in the cinematographic field.

The coming into stage of television, triggered an absurd battle between the small and the big screen. An infinity number of parties from one or the other medium suddenly leaped to enunciate ludicrous theories about language, aesthetics, the social or ‘cultural’ incidence of cinema or television.

Nobody, or almost nobody, bothered to adopt a fairer perspective: that the apparition of this new technique could mean an extraordinary vehicle of dissemination of its products (films, etc.) to an ever-growing audience.

The war between cinema and television had disastrous consequences for media.

Cinema, at the beginning, tried to defeat television by shaking the exhibition screens at cinemas, generalizing the use of colour and disproportionately increasing the production costs (which only achieved to make it harder for new creative talents to be incorporated in the progressively stagnated structures).

Television, by its part, took great advantage of the initial times of attraction that are always generated by novelties, it was benefited by the new living conditions that coincided with its appearance: traffic problems, urban decentralization, etc.

Barely introduced, and aimed at accelerating its dissemination, it made an effort for making its ‘shows’ progressively popular: the games, the songs, the journals and the most banal comicalness, were the vectors for its impetuous penetration.

To counteract television’s success, cinema tried by every mean to retain its audience, which was deserting from the screening theatres. It then produced more sensationalistic and vulgar films, and simultaneously, it disguised its merchandising intentions with an advertisement made by opulent words: ‘beauty’, ‘intellectuality’, ‘commitment’, ‘thirst of liberty’, etc. But the only certain thing is that cinema started to debase progressively, with scandal and obscenity.

The Cinema Crisis

Cinema is currently going through a severe crisis.

Television has deeply settled in our daily life. Although it performs a very similar role everywhere, its organisation varies from one country to another. In certain countries the so-called commercial television predominates: United States constitutes the best example for this. North American television sells almost all its broadcast hours to advertisement. And consequently, their shows are conceived to attract the biggest amount of television spectators, because the increase in the audience ratings determinates a proportional increase in the advertisement income. Thus, for every eight or nine minutes of a show, one or tow minutes of adds parade through the small screen.

In other countries such as France and Italy, the television is a state monopoly. In those countries, the televisual organization is funded according to a cannon that the T.V. owners are forced to pay (in a matter of fact, the owners of radio apparatuses are mortgaged by a similar canon). Thus the French Radio-Television stations or the Italian RAI-TV collect yearly thousands of millions (of ancient francs or lyres) as a compensation for the services they provide to the television spectators throughout the year, and whose nature is freely decided by the criteria of these organisms.

Definitely, while cinema has to conquer every time, film by film, the spectators who pay for its production, the monopolist state television broadcasts programs to previously guaranteed spectators, who have paid beforehand: it enjoys, then, of an incomparable privilege.

In Italy, cinema and television have almost equivalent annual budgets: three hundred thousand lyres each (more than five hundred million new francs). Not a lot of imagination is required to understand the advantages that would report, both to the industries and the audience, the accumulation of both budgets, complementing one another instead of competing. We will come back to this issue.

Anybody with an idea of cinema, as small as it might be, knows that the adventure of producing a film is only possible when the minimum budget is guaranteed (under any of these formulas: presale, coproduction, advance on tickets, etc.). But even those precautions are not enough to reduce or eliminate risks. Cinema, then, seeks shelter in the repetition of commercially successful formulas, exploits the tendency. How long are those formulas valid for? We know from experience that, as much in cinema as in any other field, the tendency lasts ‘the blink of an eye’.

Cinema is thus condemned to Sisyphus torture, it is a slave of a system that forces it to start from scratch, to assume once and again the risks implied on guessing the successful in the timely quest of what audiences will enjoy, and all of these within an incredibly short amount of time.

At its beginnings, however, cinema regulated a very different direction: its great moment coincided with the time when North Americans turned the old English saying ‘the goods follow the flags’ into ‘the goods follow the films’.

Films meant in that time, in effect, an insuperable force, a sovereign medium of ‘institutional’ advertisement for a great quantity of new products: from the car to the fridge, from the vacuum to the toaster, from the fan to the telephone and the electric shaving machine. In one word, the one thousand and one products that were precise imposing to society (that was not yet a consumer society, but was about to become one). And cinema, contributed in that sense to the dissemination of the new models of life, to create other necessities and other desires. Cinema has been a medium for entertainment and, simultaneously, the Trojan horse for the consumption society. While those were the operative conditions for cinema, the funding posed greater problems, because the capital enjoyed completely independent advantages of the success of the film. The production was abundant, and its abundance allowed, even if slowly, to widen the limits of cinematographic art, to try –even once in a while- new experiences.

Conditions have drastically changed today. The institutional advertisement has fallen in disuse, as it has not a reason of being and has achieved a good part of its fundamental purposes. From that point of view, the function of cinema and television is different nowadays: they are not useful anymore to foster a determined type of society, as the films from other time did, but they play their role as the ‘opium for the people’ and make everything within the possible –I am not sure if in a way of tropism or consciously– to keep the masses in a infantilism state, moved by the fanciful sufficiency given by the illusion of freedom. This infantilism is convenient, without doubts, for the leading figures of our society: it facilitates the propaganda that leads the masses towards the alternative that the power or the pressure groups create.

A Service of General Interest

A national television is only justified if it really is, as the law prescribes, an ‘indispensable service with a character of general interest’ and ‘participates in the cultural and social development of the country’.

For achieving a cultural promotion at the service of the people, the diverse television stations (at least those from the state), the parliamentary control organs and the unions should put into practice new procedures for the television shows to contribute to the democratization of the country. Which purposes should be proposed and which methods? Regarding the purposes, one shall remember what the great currents of contemporary thought, from Christianism to Islam, from Socrates to Marx have stated each in their own way: the only possible purpose is that of making human society to mature. All these current of thoughts share a common base: faith on men. Mahoma himself has said that the diversity and variety of human intelligence were the proof and existence of God’s generosity. Science proves him right nowadays, by demonstrating the multiplicity of intelligence. It is a richness we have to take advantage of.

Regarding the methods, television could develop a cultural promotion within everyone’s reach. As it make use of images, it would overcome the teaching difficulties, if there is some true in Comenius’s affirmation, in a great extent: ‘the difficulty on learning comes from the fact that things are not taught to the students through direct vision, but through very tedious descriptions that print the image of things in the intellect with a lot of difficulty; they penetrate memory with such softness that they are easily vanished or are understood differently from the correct way’.

Television could provide a ‘direct vision’ of things, of men and of the history of millions and millions of individuals. History teaches us that social changes –unavoidable insomuch as we are destined to evolve towards a better world- follow the new thinking systems. But thinking systems only evolve when men are able to recapitulate what they know. For that, informing everyone is crucial, putting knowledge within everyone’s reach, and it is crucial as well to constantly update this knowledge. In one word, knowledge must be democratized.

Is it possible for men to accomplish its integrity, as it already happened two or three times throughout history? Yes, as long as all men, or at least the majority, are able to recapitulate the greatest quantity of data as possible. With this purpose, it is necessary to develop a cultural information addressed to all, disposed to disseminate all knowledge and ideas. Then, and only then, all men will be able to make synthesis and orient their minds in such a way that they make possible new developments. We would thus reach the harmonious participation of all the individuals in social affairs.

This would be the ideal, naturally.

Practice, unfortunately, is very different. Television ignores this principles and cinema does so even more.

The initiatives of cinema in educative matters are null. Television, as opposed, has settled some objectives, but all its teaching efforts are calqued from the school model, including the professional schools. However, there is a distinguished exception in Italian television, the television film series called ‘Sapere’. Except from it, television, in the image of school, does not seem to have any other purpose but helping students to ‘have a career’ within the margins of the current system. Gramsci affirmed that the traditional school is an oligarchy, because it is addressed to a generation of men whose unique destiny is to govern the country. I will add, on my behalf, that these future ‘governors’ are, in fact, docile and submissive because they have limited horizons. Television, for the common wealth, should foster those information and cultural forms that the school does not provide and that will help with the development -due to consciousness and not to propaganda- of a rigorous critical sense, crucial to the progress and the evolution of the social current structures. Such evolution would serve everyone’s interest, both the privileged and the dispossessed masses.

Apart from the necessity to modify its purposes, creativity is the fundamental factor for television and cinema to survive. If a collaboration was to be settled between both structures, the possibilities of fostering the inventive spirit would increase undoubtedly, with the consecutive repercussion for the benefit of ideas. We have seen that in Italy (as it happens in more or less every country) the budget for television and cinema are equivalent, around tree hundred thousand lyres, despite the television spectator are more numerous than the usual clients of the cinema theatres.

If television participated in the cinematographic production, it would share the film’s income, thus relieving its dependency on advertisement. The media workers would enjoy a better guarantee of their jobs. A wider and healthier market would permit to carry out the cultural promotion operations we have previously referred and which would contribute in training minds: an ‘integral culture’ would have thus a better chance of turning into reality. These promotion methods, once improved, would stimulate the implementation of new audiovisual media (videocassettes, etc.) - of which so much has been said and so much money has been invested, vainly for the moment.

This text collects part of Rosellini’s Speech in the symposium «L’engagement social et économique du cinema» which he organized at The Cannes Film Festival on the 13th and 14th of May 1977. It was published in: ROSSELLINI, Roberto (1977). Un esprit libre ne doit rien apprendre en clase. Libraire Arthème Fayard. Paris. Translated to spanish by José Luis Guarner in: ROSSELLINI, Roberto (1979). Un espíritu libre no debe aprender como esclavo. Escritos sobre cine y educación. Gustavo Gil. Barcelona.

Nº 7 HOW FILMMAKERS THINK TV

Editorial. How Filmmakers Think TV

Manuel Garin and Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

Cinema and television

Roberto Rossellini

Three questions about Six fois deux

Gilles Deleuze

Birth (of the image) of a Nation

Jean-Luc Godard

The viewer’s autonomy

Alexander Kluge

Cinema on television

Marguerite Duras and Serge Daney

Critical films were possible only on (or in collaboration with) television

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Medvedkin and the invention of television

Chris Marker

TV, where are you?

Jean-Louis Comolli

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Between film and television. An interview with Lodge Kerrigan

Gerard Casau and Manuel Garin

ARTICLES

Ten founding filmmakers of serial television

Jordi Balló and Xavier Pérez

Sources of youth. Memories of a past of television fiction

Fran Benavente and Glòria Salvadó

Television series by Sonimage: Audiovisual practices as theoretical inquiry

Carolina Sourdis

The televisual practices of Iván Zulueta The televisual practices of Iván Zulueta

Miguel Fernández Labayen

REVIEWS

JACOBS, Jason and PEACOCK, Steven (eds.). Television Aesthetics and Style

Raquel Crisóstomo

WITT, Michael. Jean-Luc Godard. Cinema Historian

Carolina Sourdis

BRADATAN, Costica and UNGUREANU, Camil (eds.), Religion in Contemporary European Cinema: The Postsecular Constellation

Alexandra Popartan