SOURCES OF YOUTH. MEMORIES OF A PAST FUTURE OF TELEVISION FICTION.

Fran Benavente and Glòria Salvadó

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHORS

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHORS

We easily forget that in television, as in other fields of culture, Europe marked the pattern of modernization. Today, after celebrating a new golden age of television fiction (fundamentally American), talking about complex storylines and raising our glasses to celebrate the rise to power of the television “author,” we could ask ourselves, perhaps: What is the author in television? Or, better yet, who is the author in television? There is a movement that marks a change of arms in contemporary television fiction from the executive producer to the writer producer or the showrunner. However, this line is inscribed in an institutional story, the one of television fiction in the setting of entertainment logic.

But there is another story, which took place fundamentally in Europe, with another answer to that question. That story is about the remains of past television worlds, beautiful utopias without apparent progeny that marked a possible, and perhaps better, future for television. In that story the answer to the question about the author is: the television author is a filmmaker. In that story television fiction is an invention of cinema; or, at least, a consequence. The filmmaker as a television author sees a possible experimentation space and rehearses a way of adapting his writing on the basis of the specific strengths of the medium but without renouncing to the significant substance of his stroke. He glimpses a solid project, unique, but problematic for the medium and not always easy for its spectators. That is why it is usually utopic, because it is given up or does not leave offspring or traces in its environment, even if the seeds of its influence can be everlasting.

It is an almost sacred story, with its apostles, converters and illuminated, with its revealing moments. One of them, very well known, takes place in October of 1958, when the filmmakers’ television utopia becomes visible in a publication –France Observateur– in which a group of news reporters, amongst whom André Bazin can be found, interviews Jean Renoir and Roberto Rossellini; one about to embark in the television adventure, the other already immersed in it, in the prelude of what years later would be his great work for television (ROSSELLINI and RENOIR, 1958).

Bazin, Renoir, Rossellini in 1958. No one overlooks that here is where the “patrons” of cinematographic modernity gather to discuss about television, and its possibilities, at the cinema exit, and all of it in perfect synchrony with the birth of that cinematographic modernity they have incubated, preceded. Cinema and television, a then young couple that, nevertheless, already looked alike. And we shouldn’t forget that the magazine Cahiers du Cinéma was, from its beginnings and during some years, a “Revue du cinema et du télécinéma.”

For Bazin, Renoir and Rossellini, that “télécinéma” was the possibility of a new origin, a fresh start full of possibilities with the addition of making true the dream of popular cinema: to reach a massive audience.

The old and the new: Renoir, television and theatre.

In 1958 Renoir is preparing his entrance in television at the end of a decade that had seen his rebirth in the Indian waters of The River (1951) and that continued in the theatre of the world with a danger of mannerism winding in, however, beautiful films such as Elena and Her Men (Elena et les homes, 1956). In opposition, television offered the possibility of the return to immediate tension, the tremor of a live show, the cutting edge of the unrepeatable. What really interests us here is not so much that Renoir passes on to television but that he does it to raise a filmic program entirely constructed on television specifics, different strengths that mark a different type of fiction, new, thrilling.

Some of those specifics are connected with Renoir’s old dreams, such as the work in progress of the scene, without cuts that disturb the actor’s work. Renoir had already experimented with different cameras, but the multiple-camera setup of the television set allows him to predict a transparent way (without renouncing to the editing) but clear of interruptions. Renoir sees in television a way of working on a cinema focused on the scene and not the shot.

'I am now going to try to take my beliefs farther and make the camera have only one right: to simply record what happens, nothing more. For that, evidently, we need a few cameras, because the camera cannot be everywhere. I don’t want the movement of the actors to be determined by the camera. I want the movement of the camera to be determined by the actor. Therefore, it’s about being a reporter' (RENOIR in ROSSELLINI, 2000; 152).

On the other hand, Renoir reads the transcendental principle of television in the immediacy of the live show; that which distinguishes it from cinema. In 1958 video tape recorders already existed for video recordings, but live broadcasting was still the dominant way, also in the production of “TV dramas”. A live show implied unique broadcasts and, for that, unrepeatable gestures. Renoir’s aesthetics program is constructed on these principles: live show, continuity, scene. The touchstone was supposed to be Experiment in Evil (Le Testament du docteur Cordelier, RTF, 1961), a French adaptation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

'I wanted to film this movie and television provides me with something appreciable in the sense of live television. Evidently, it won’t be a live broadcast, because it will be prepared on film, but I would like to shoot it as if it were a live broadcast. I would like to shoot only once and that the actors imagine that every time we film them the public directly registers their dialogues and their gestures. The actors, like the technicians, will know that we will only film once and that, even if it goes wrong, we will not start over.

Besides, we can only film once to not draw the attention of passers-by, who have to remain being pedestrians. It’s about filming episodes of this movie in streets where people do not know we are filming. That is why, if I have to film again, it doesn’t count. Therefore, this necessity must convince the actors and the technicians that every movement is definitive and remains recorded forever. I would like to break with the cinematographic production and build a great wall with small stones, with a lot of patience' (RENOIR in ROSSELLINI, 2000: 149-150).

In the beginning of the film, in a prologue with a “documentary” aspect, Renoir bursts in the television studios, where the editor Renée Lichtig receives him. A takeover of the television production studio as scenic space that evidences an affirmation of the world as a representation to find, amongst the breaches and the friction with reality –the actors’ bodies, the immediate– instants of truth. That is where Renoir establishes himself, in a double perspective, between the ground level with the stage (television set), the characters’ place, and a superior gaze. This axis of positions, between the control of the staging and the contiguity of reality, will be resumed in Opale’s first appearance, when he threatens a girl before the eyes of the notary, maître Joly.

In the same way, in the first sequence –the one of the prologue– the relevance of the dialectics between the inferior (of the set) and the exterior (location shootings) is introduced, which rewrites in the centrifugal/centripetal axis the vertical/horizontal vector. It’s a prevalent issue in the potential relief that television offers for the cinema of the time. Marcel L’Herbier, a then old filmmaker who had ended up in television sets, thought that television allowed articulating alchemy between the theatrical and the cinematographic (L’HERBIER, 1954). The theatrical in the sense of the continuity and weight of the actors’ work in a scenic space; and, in turn, the cinematographic prolongation of that scenic space in sequences filmed in location shootings, in 16mm, different to those interiors filmed in a multiple-camera setup. From that principle Renoir starts to link the prologue with the beginning of the story. From the world of the representation, the set, the opening to the exterior is produced. These types of frictions are what sustain and praise the project Experiment in Evil in relation to a possible fiction program for television.

In truth, it’s about making the artificial and the natural clash to discern reality. This principle is also combined in the exterior scenes and in relation with the actors’ work. The alchemy between theatre and cinema operated in television as a space of encounter also works between the control of the character by the actors—that come from theatre and work a body language and characterization that are in this line, from inside out –and their placement in a situation of immediacy of register and, in the case of the exterior scenes, of a more or less hazardous reality, with the necessity of improvising in their encounter with the world. These sequences were supposed to be filmed in one take, bringing theatre to the street and taking the world as a stage and the passers-by as extras. It’s about, again, seeing what happens in the friction between mechanisms.

Between the surface and the depth is where the last of the dialectics is produced, in this specific case of the story. If what it is about is to see how a hidden and repressed inwardness –Opale– breaks the veil of a surface –Cordelier–, Renoir will work on the animal, hysteric, brusque (and burlesque) gesture that disrupts the delicate surface of the bourgeois mannerism. The interpretative register of this work is broad and varied. That work of surface and depth finds its eco in the scene of Opale’s first appearance, when he is chased on the surface of the wall, in a sequence filmed in continuity, only to disappear through the door of Cordelier’s house into an unknown interior.

Experiment in Evil is a more than notable film, synchronic and brother to the concerns of the Nouvelle Vague. As a television adventure, however, it is not more than a relative success, as it wasn’t able to respond to the “radical” initial project. Àngel Quintana has explained the details of the story: the initial plan was to film in direct video, in real time, an hour and a half, preceded by three weeks of rehearsal with the actors and two days of technical rehearsals (QUINTANA, 1995). The make-up problems and the work in location shootings caused the idea to be abandoned for a movie prepared on film, shot in cinema with a live vocation. The rehearsal and filming days multiplied. Television became a financial source and favored a work system in the rehearsals that hoped to also reconcile the theatrical and cinematographic logic, a kind of collective creation, and a logic of telefilmed dress rehearsals.

So Renoir, with an extreme program for the future of his fictions as television fictions, doesn’t achieve the full realization of the utopia but instead leaves a beautiful example of cathodic fiction for history. However, the problems that emerge in Cordelier will be those that explode in Renoir’s next work for television –Picnic on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1959)– and that, in the end, will make him abandon television as utopia disenchanted, only to go back at the end of his career for a purely financial necessity (with The Little Theatre of Jean Renoir [Le Pétit Théâtre de Jean Renoir, RAI-ORTF, 1969]).

Serge Daney said that television, since its birth, found itself between two simultaneous vocations: the opening to the exterior, the window to the live world; and the confinement and separation of the world in the set (SABOURAUD and TOUBIANA, 1988). The centripetal power of the TV play was imposed in fiction, its theatrical logic filmed. Instead, Renoir saw clearly that beauty was starting from that artifice to open all its breaches to an outside, towards the other, towards the truth. And, in that trance, to offer an image of the world (starting from the question on technique and dehumanization).

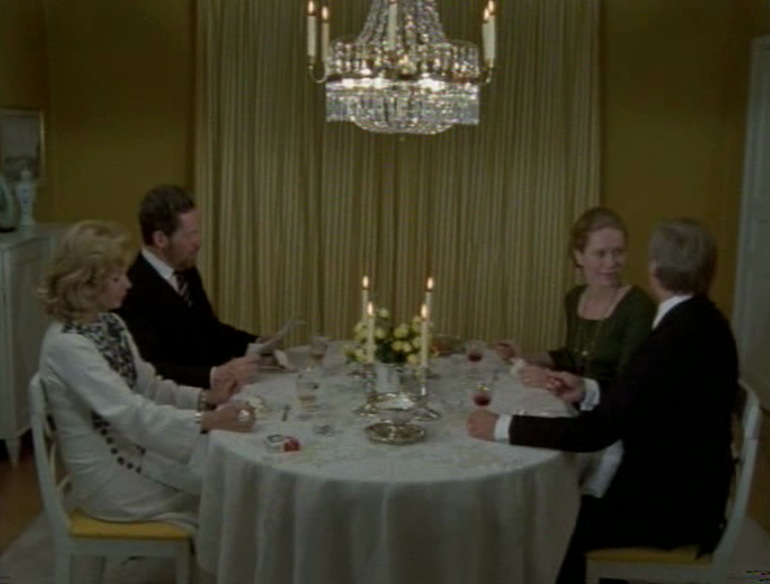

From Renoir we can inflect this idea of the filmmaker who starts in television, by choice or by need, confronts the medium, tries to delve into its specificities, to generate an adaptation work of his own style that becomes profitable, that marks a fertile moment in the history of television fiction (frequently not well known). For example, a filmmaker like Ingmar Bergman considers television as the prolongation of a kammerspiele theatre filmed and elongated for hours. His real television project consists in detecting in television fiction the possibility of accentuating the intimate aspect inherited from theatre, and insisting on it in the long duration of the story that the medium permits, from serialization. In this way Scenes from a marriage (Scener ur ett äktenskap, TV2 Sverige, 1972) is born, a study about the decomposition of a couple, very much in line with Bergman’s style, but that reaches levels of clear emotion and dazzling freedom from the restrictions imposed by the medium and the highlighting of the idea of theatre: long scenic segments on set, face and body of the actors as the center of the story, supremacy of the word, dramatic concentration and big ellipsis, etc. With these aspects, Bergman will achieve one of the biggest works of his filmography and a great public success in Sweden, with direct involvement in social topics such as abortion, adultery, etc.

The language of experience: Pialat, the feuilleton and the realistic novel.

We find another brilliant moment in the history of French television fiction toward 1970, not much after the year ’68 and in full peak of another cinematographic movement, the so-called post-nouvelle vague that would run in parallel and in close relation with the things that were happening in television. We will now talk about Maurice Pialat’s stunning passing through television. If Bergman had worked by taking to the extreme the theatrical accent of television fiction, Pialat will choose to explore the parallels of television fiction and a certain tradition of the realistic novel.

Yves Laumet, who in those times worked as an artistic consultant for co-productions in Antenne 2, the second channel of the French public television, had seen Naked Childhood (L’enfance nue, 1969), Maurice Pialat’s debut, a severe and sharp reflection of a non-reconciled childhood and the need of love that had supposed the debut of a singular filmmaker, unaffiliated to any particular school. Pialat had other projects, but Laumet thinks he is the suitable person to film the script for a feuilleton written by Renée Wheeler that talks about the life of the family of a French forest ranger who, during World War I, takes in children whose parents have gone to fight at the front.

Laumet presents the project of La Maison des Bois (ORTF, 1971) to Pialat and he accepts (MÉRIGEAU, 2003). The economic reason is not the most important one, rather, a double possibility that the television format offers: the long duration and, again, the possibility of reaching a broad public. We must remember that Pialat always aspired to be a popular filmmaker –not a director for initiates– and this was the opportunity to secure a work in this sense.

We have here an unusual utopia as we find ourselves facing a one-time passing. Pialat will never work in television again but, nonetheless, his adventuring will remain as an unknown masterpiece (until relatively soon) and as one of the filmmaker’s favorite works. A relevant case, and without a doubt transcendent, in the history of television made by filmmakers.

As we have said before, for Pialat it’s about making the most of the advantages that the medium offers –specifically the extension– to work on a Flaubertian form of realism, dissolving the story in the air of the everydayness, bringing the rhythm of the events closer to the passing of life and working the broadcasting, in an apparently calm environment, of the echoes and traces of a tragedy happening in the background, history, the events of World War I. It’s about seeing the lives and the details drawn on that conflict, and also see the customs and life in the country, the image of a France that transforms slowly and gets lost. The story of a maturation, a death and a change.

Pialat rewrites the script completely with the help of Arlette Langman, and sees in the story of these children taken in during World War I a projection of his experience during World War II. Of the six episodes initially planned, the series will include seven, which shows the importance of time and the breathing it allows. Joining the coral panoply of characters typical of the feuilleton, Pialat is able to compose a community portrait taking his time to pause in gestures, actions and quotidian faces; to abandon the central line and get lost in the ins and outs of the story; to follow the calm pulse of the life pierced, suddenly, by the darts of the melodrama. This is the Pialat system in La Maison des Bois, to linger in the flowing of daily life to better break it in certain, and terrible, moments of drama. That form of observation of a light life on a dramatic background takes form in a light cinema, in which the filmed material goes beyond any formal logic. Pialat uses long shots, indistinctly fixed or in movement, traversed by corrections that allow, even, the use of the zoom. Everything very far-off from the gravity of Naked Childhood.

The first dramatically charged event in the series, the death of the marquise (the wife of the place’s landowner), bursts in through a messenger who brings the news to the schoolteacher (Pialat himself). The news appears after a long class sequence where the teacher Pialat makes the children recite while they live the tension and nervousness combined of the question in class and the filmed scene. Pialat, as usual, looks for the surprise, the unexpected natural detail and, for that, directs the scene from the inside. Shortly after, at the marquise’s funeral in the church, Pialat chooses to privilege the anecdote of the children, who act as altar servers, in their relationship with the old sacristan and how they all sneakily drink the ceremony wine. It is a jubilant scene, which settles a childhood experience, provincial, with no importance for history but decisive for the memories of life. It is a scene filmed in long careless shots, attentive to the luminous faces and tentative gestures. In one moment, the sacristan loses his hat and it falls on the wine, which spills. It looks like one of the accidents that Pialat incorporates in his fictions. In any case, this trivial scene of long duration, filmed in an unnoticed and almost careless way in its naturalness, contrasts with the stiffness of the tracking shot that comes in by cut and walks, in the middle of the church aisle and the symmetry of the frame, towards the encounter of the marquise’s coffin.

Pialat works the Flaubertian realism (although he prefers Dickens, of whom there is something in the portrait of these children who live their small joys in the midst of a life of misfortunes) in the sense of a composition of daily reality seen in a prismatic way, as a conglomerate of disperse fragments, and fixed in an almost photographic way, linking details to draw an approach to the full shot of history and life. The psychological portrait isn’t as important as the sketching of sensations and experiences, their links. That Flaubertian realism has its correspondence in something like Courbet’s evolution of pictorial realism to the impressionist stroke, pictorial moment that, as we know, is synchronic to the writer’s narrative.

The scene that could finally summarize all of this would be the very long fragment of the third episode that corresponds to an escape of the story and an escape of the characters to rehearse that clearly identifiable motif of the “luncheon on the grass.” Indeed, the ranger’s family dedicates the Sunday to a picnic near the lake, a moment of joy about to disappear. There they eat, rest, they talk about trivialities, the boys play, ride the boat, the ranger’s daughter talks about love and Albert, the natural son, announces that he will join the army. This part of the episode invokes, as the whole series, Renoir’s spirit, it tastes the form and taste of a universe about to be broken, it fixes the trivial experiences, the moments of suspense, that will remain in the memory of the people of a France that will never again see itself in that way. The pleasure of the everydayness and the sensitive connection with the world. The fascination for the ordinary, and its pleasures, seen as an isle of joy.

The discovery of death and disenchantment will be the resulting movement of the dissolution of that paradise about to become lost. The chain of events will be read as the son’s death, Albert; the main character’s return to Paris, Hervé, to reencounter the father and a “new” mother; and, finally, the ranger’s wife’s death, Maman Jeanne, the “great mother” of the woods and the children. This is the learning and the climax of the drama that Pialat presents as the ending of all that was lived at length in previous episodes.

Maurice Pialat has found a television form for the feuilleton that exalts and squeezes it in its possible opening to the world and its secret rhythms. A way of reconnecting popular television with the novelistic formula, but not dedicated to unlikely and bookish events, but in the descriptive plurality of the details of everyday life. That has nothing to do with the marginal or the experimental. Pialat works with popular actors, in a time, a context and a landscape recognizable by the French. He even connects with the Buttes Chaumont studios (the traditional school of TV drama within French television) and with the literary tradition of French cinema previous to the Nouvelle Vague. He is demanding, though, and respects the medium and his spectators. That is why his “series” has the beauty, the length and the aspect of great works.

Television on the air: David Lynch and the live broadcast.

We can also find examples on the American side. David Lynch is the most known paradigm of what a filmmaker can do in television fiction when a good review of its limitations in relation to cinema is made ('in cinema one can interpret a symphony but in television one is limited to a screech' he will say) and, however, one works with its specific advantages ('the only advantage, the screeching can be continuous' LYNCH in RODLEY, 2005).

Beyond Twin Peaks (David Lynch and Mark Frost, ABC, 1990-1991), Lynch still wanted to continue exploring the medium in search of new challenges and frontiers. From his association with Mark Frost, he faced ABC’s assignment to conceive a new series. The strong gesture consists here in trying to abound in another television specific and, more specifically, in taking television as an object of comical experimentation. The result is a comedy of a strange situation, impossible and largely ahead of its time. Of On the air (David Lynch and Mark Frost, ABC, 1992) only three episodes were broadcasted and four more were filmed. Its pilot deserves to appear amongst the most noteworthy reinventions of burlesque in recent history.

So David Lynch, in this case, carries out television fiction from the own television reference and the identified paradigms, from its origins, with “televisuality”. From the very title, the project focuses on the idea of the live show (“On the air”) that was the catalytic idea of the television specific in the early times. Here there is a complex game of references and a return to the origins. The series takes a television broadcaster in the 50’s as setting. The ZBC (Zoblotnick Broadcast Company) kicks off a broadcast of live variety acts with which Lester Guy, a run-down movie star, hopes to revitalize his career. It’s about going back to Lynch’s favorite decade and continuing his work of deepening and cracking of the imaginary tissue manufactured in those times of innocence and superficiality.

The project is summarized in the initial generic. Lynch’s intention is clear, to explode, from its origins, the naturalized flux of television broadcasting, to break its continuity, to show the holes that mark the inconsistency of that imaginary and imagined surface, investigate how that screen of joy shows, amongst its breaches, the emergency of the absurdity it constitutes. It’s an operation of satiric critique that uses the tools of the burlesque comedy, with all its display of gestural hysterics, corporal violence and its work of unproductive reduction and language anarchy. That means to not only take television against the grain, but to break all the rules of the sitcom constructed on the chained exchange of witty dialogues. We can see how cinema, the filmmaker, revolutionizes a traditional form of television fiction by shaking the principles of the own television (taken at the moment of its genesis) and making them enter a complex circuit with cinema.

On the Air can be understood as an image of reality (an image of American society) consumed by the rupture of its foundations: continuity, simplicity, innocence. It is television and what it signifies, what constitutes its space, what will be disassembled, saturated, destroyed.

The use of language corresponds to this disassembly of the space (or the image of the space), of a clearly burlesque root. As we said before, the series bases its idea of dialogue in misunderstandings, the difficulty of communication and the absence of fluidity. The key is the character Gotchck, Zoblotnick’s central European nephew who directs the program. The problems with English of this character, a poor devil working there by nepotism, generate an unsolvable and comical short-circuit in the transmission chain of responses. An example of the rupture of the dialogue chain and its reductio ad absurdum clearly appears when Gotchck and Ruth, the production assistant, find the program’s producer and Betty, the feminine star that will accompany Lester Guy in the new The Lester Guy Show. The dialogue becomes impossible and absurd, like a defective game of Chinese whispers in which one always translates wrongly. On another hand, Gotchck’s English reaches, in its incomprehensible gutturality, the pure interjection. Moreover, Lynch rehearses an abrupt tempo of the response exchange, not fluent at all, as if in every one there were a skipping or an interruption. This idea of breach and rupture of the naturalized flux spreads everywhere and it is not easy to digest for the common spectator.

Lester Guy, a decadent actor, acts like a star in the new frame of television and considers everyone that surrounds him to be an idiot. In the reversal logic typical of the burlesque, the one who turns out to be an idiot and ridiculous will be, mostly, the very own Lester Guy. In a way, it’s a transplanted version of the character that the same actor, Ian Buchanan, played in Twin Peaks. So is the character that Miguel Ferrer plays, the executive Bud Budwaller. In Budwaller’s appearance and his pep talk to the employees the short-circuit of the word is reproduced, constantly interrupted by the unnoticed sound effects activated by mistake by Blinky, the blind sound technician. This chain of comical interruptions and sonorous startling, that break the discourse, anticipates the relevant role that the sonorous asynchrony (and, therefore, the work on sound) is going to play in the decomposition of the television world.

With this layout the pilot finds its natural structure in the dichotomy rehearsal/live show, staging and broadcast. We see the rehearsal of the initial program of The Lester Guy Show from the staged distance, from the screen or the frontal shot, more or less distant, and everything flows naturally in its original innocence. A typical romantic fiction sponsored by a brand of dog food, sustained by the music and the sound effects. Versus this staging of the television image in its original construction, a broadcasting full of accidents, sabotaged until the absurdity, the nothingness and the void.

At first, the rebellion of the space comes, in the best comical tradition. This will be one of the principles applied by Lynch, the progressive conflict of the set and the bodies that inhabit it will be extended to a generalized asynchrony and difference, which will find its main trigger in the lack of coherence between sound and image. That’s how it goes, facing the initial disaster, Gotchck loses control spiking up the nerves. The red phone gag, with Zoblotnick on the other end, symbolized by a tongue of shining fire, points to the exaggeration of the destructive cartoon, tradition to which Lynch appeals with pleasure.

In the confusion of the moment, Budwaller presses a red button of warning. That button will provoke a movement of the sound effects’ control panel that Blinky cannot notice. The light movement of the control panel will be enough to move any effect and, therefore, to break with the synchrony of the world of the images and the soundtrack that sustains it. From there the guiding principle will be that of excess and saturation. Where in rehearsal there was only surface observed from a distance, in the live show the step to the interior of the scene reveals all its incoherence and disconnections, indescribable comical dislocations that destroy any sense and throw, in a chain of accidents, blows and falls –always driven by ludicrous sound effects– that show the inconsistency of a broken and totally inverted world.

Finally, the scene, insane, is saturated from all the visual elements and, above all, all the superposed effects activated by Blinky in total desperation. It’s the rule of the Marx brothers’ anarchism reinterpreted by Lynch with sound. Wear out the scene by excess, disturb it, let the noise show itself as unbearable texture of the image.

This rigorous burlesque work on the disconnection of figure and ground, surface and depth, image and sound, will end up turning a normal variety show in a singular success. This will be the series’ premise that will develop in the remaining episodes. Nevertheless, it was foreseeable that this absurd vision of television’s foundations was not going to find an audience. Let’s say it could not find it yet in a decade in which Seinfeld (Larry David y Jerry Seinfeld, NBC, 1989-1998) was barely finding its way.

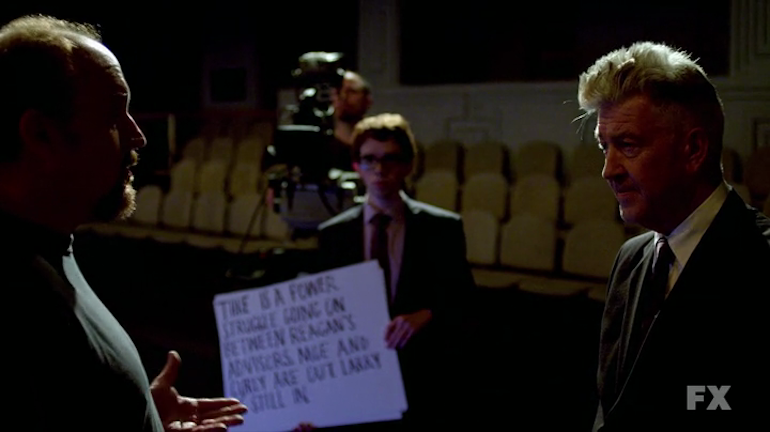

The consequences of Lynch’s work in the conjunction of time and editing to construct a humor based in the absurdity, the incommodity and the lack of linking and understanding between the characters and the images, the body and the television situation, are seen much later. Today’s most advanced comic series, Louie (Louis C. K., FX, 2010-), articulates in three episodes of the third season the revival of this survival, agitates the postponed legacy bringing up, as it could not be any other way, the creative body of David Lynch.

In a thematic arch that goes from the 10th to the 12th episode of the series, Louie runs for the substitution of David Letterman at the front of NBC’s Late Show. His opponent will be none less than Jerry Seinfeld (the maker of the revolutionary sitcom that triumphed in a synchronic way as On the air’s failure). Louie faces with disgust and lack of harmony his entrance to the world of the great television business. Unaccustomed, he will be sent by the network to undertake a training with a private coach, Jack Dull, played by Lynch. The latter appears in two scenes of episode 11, both stellar moments of contemporary television.

In the first scene, Louie arrives at Dull’s office, Dull being as deaf as the character that Lynch plays in Twin Peaks (and keeps a gun in the drawer). The issue of the first encounter is, nevertheless, the question of time. Lynch makes Louie read an anachronistic joke about Nixon while he times him. The joke’s displacement, it’s non-humorous nature, the delay in time, the lack of fluidity and speed, and the insinuation of the void as a center mark the new points of interest of the comic scene seen from the transmission of the master to the disciple. This coaching doesn’t come from Twin Peaks, but from On the Air. This is confirmed in the second scene where Dull and Louie meet. It’s about a camera test in which Louie must interpret the Late Night’s welcome in an empty set, and tell a joke, also anachronistic, addressing an inexistent audience. Louie, uncomfortable by the absurdity of the situation and the lack of adaptation to the space, is victim of the interruption and lack of fluidity. Dull-Lynch bursts in the set and acts the scene while Louie watches him from the camera. What happens is a comical effect derived from the absurdity of the scene seen from the inside, with Dull waving toward the emptiness, and what Louie sees (and hears, as a spectator), amazed, through the camera: the same scene but mixed with music and applause from “impossible” spectators. It is the dialect between the essential void of the medium and the fluid entertainment that emerges on screen. In that breach, that On the Air delved into deeply, Louie lives his adventure as a possible substitute to Letterman. To remind us about the nature of that field opened in the sitcom, the body of the filmmaker that started bringing it up many years ago appears, the one of the mentor-master David Lynch.

Sketches for the ear: Orson Welles, from radio to television.

We have seen different specific projects made for television by filmmakers working in the orbit of some of their original sources: theatre in Renoir or Bergman, realistic novel in Pialat, televisuality in Lynch. We can complete this approach with another filmmaker that approached television with a clear idea of how to explore it in a specific way also from one of its sources of origin.

Orson Welles was interested by it as an extension and amplifier of the power of radio, another of the mass mediums in which he had already triumphed. With this premise, Welles burst in television in a revolutionary way. His revolution would take form, mostly, in the development of a form of audiovisual essay, as a piece to reflect on and think about founded in the editing, the mixture of fiction and documentary and the inscription of the reflexive voice in the tissue of the piece. Working from the portrait (Portrait of Gina, ABC, 1958) or the travelogue (Around the World with Orson Welles, ITV, 1955; Orson’s Bags, CBS, 1968), it was about showing Welles’s thinking in movement, forming itself, about a particular topic or place (as frivolous as it were), making a story by constructing the truth from the power of fakeness. This entire television laboratory will lead to that film beacon of modernity that is F for Fake (1973), truly influenced by Welles’s work for television.

Welles’s relationship with television began in his European period, after the failure of Macbeth (1948) and before his return to the U.S., in 1956. It will be in London where, supported by the BBC, Welles will find the first spaces to investigate in his idea of television. The result will be six broadcasts titled Orson Welles Sketchbook (BBC, 1955), of barely fifteen minutes each. It is a simple mechanism, Orson Welles, sitting in a chair, sketches different drawings while he explains stories of different nature to the spectator. It’s about conceiving television as a conversational device similar to radio, in which the narrator takes advantage of the intimacy of the medium to whisper in the ear of his interlocutors, in all familiarity, and to sketch vague images (conscious of the visual poverty of the medium in opposition to cinema) to elaborate a story of experiences that refers to the figure of the ancestral narrator, the wizard, the magician.

The objective is to densify the enchantment of fiction from the power of the voice and the word, and make it (this is the great seed that Welles plants) from the sketched form, interrupted. Significantly, the first story that Welles tells is about a personal experience (Welles always talks about himself) in which he is telling a story to his friends in a restaurant in Los Angeles. The story is interesting but Welles does not remember the ending or does not know how to finish it. On the threshold of the disaster of the story, an earthquake appears as Deus ex machina and saves the narrator. The ideas of the fascinating but inconclusive story, the story that stands on its own feet, and that is about the very idea of storytelling, signals the entrance figurehead of Welles in television.

The fact of him being the narrator does not surprise, such as his all-embracing figure acting as a perfect middleman, absolute voice, between the spectator and the narrated experience. Welles addresses the camera, looks the spectator in the eye, questions him. This dialogic form (or monological, it doesn’t matter) of television has an impact on forms of what is sometimes named “paleotelevision” (the same way people talk about primitive cinema) that in the end founds strictly revolutionary projects that open new ways, for example, for cinema. Here Alexander Kluge’s project, based on conversation and the editing process with drafts and fragments of images is not, actually, that far away.

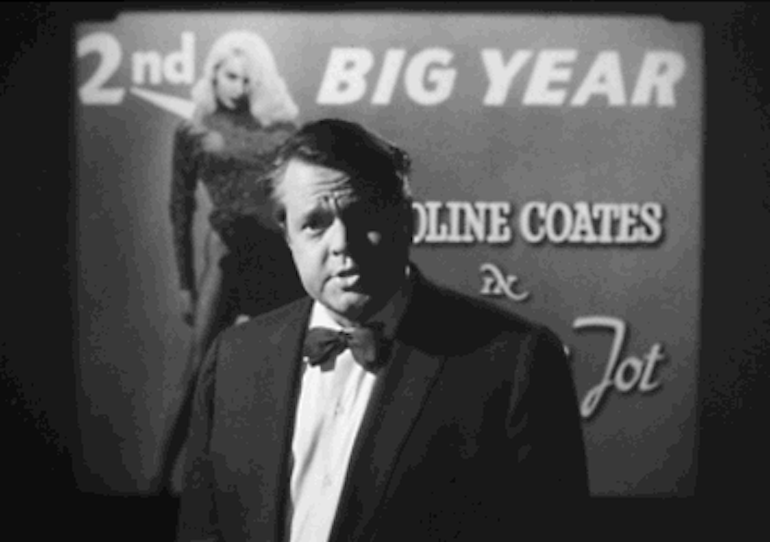

The small fragmentary form, notebook, essay draft, will be more defined in Around the World with Orson Welles, the series of journeys he started immediately after for the ITV. But we are interested in pausing, to finish, in the way that Welles conceives his only strictly fictitious piece for television: The Fountain of Youth (NBC, 1958)1. The piece is a half-an-hour long drama requested by the producer Desilu as a pilot for a possible anthological program made with adaptations of short stories. Nevertheless, the singular formalization of this piece resulted in the non-production of the series and the broadcasting of the pilot years later in the setting of the Palmolive Colgate Theatre, one of the many anthological spaces of television adaptations of theatrical dramas or current literary works.

What Welles suggests in The Fountain of Youth is a distillation in the terrain of fiction of his ideas about television. He takes control and the center of the story, unfurls stripped settings, retro-projections and mixes the dialogues with narrated photographs and illustrations. He rehearses set changes on camera and investigates about the sound form and the voices of the story to construct a reflection about the vanity of appearances, the fear of growing old and the passing of time.

The emission narrates the story of a scientist who falls in love and expects to marry Caroline Coates, a young actress with no talent, vain and banal, but with great physical beauty and much younger than him. The scientist, Humphrey Baxter, must leave Europe for some years to research. When he comes back, he finds out that the young actress is about to marry a tennis star. Baxter spreads the word, then, about having synthesized a serum for eternal youth. The scientist offers the serum to the couple as a wedding gift, but there is only one dose that they cannot share. The serum, which is false, will act as a revealer of the vanity of the presumed lovers.

Amongst the things that we should highlight of Welles’s “program” of television fiction is the author’s omnipresence. As he did in his radio fictions, Welles talks in first person singular, he narrates, he bursts into the story and he even says the characters’ dialogues. He is the great imaginator and, actually, the main character, of this chain of vanity and falseness. But the affirmation of the voice and the presence relapses into already explored resources in radio and that will reappear in his cinematographic essays.

Welles manages the characters at his will and finds his first representative figure in Baxter, the scientist who also creates a plot to manipulate the characters at his will. Welles shows, plays, marks transitions and, of course, addresses the spectator directly. The story and its construction ways are again the center of the story, and television, as a radio with images, reinforces the function of enchantment of what is narrated, story for the ear. In this sense Welles assumes the poverty of the image, constructed from the note or the evocation (let us remember the concept “sketch”): transparencies, simple sets, few significant objects, centrality of the word and density of certain sounds. In this sense the presence of microphones or the enormous phonograph of Baxter’s laboratory confirm that the image is offered to the ear, that it speaks to the eye. In the same way, the sound of a clock’s ticking during the scene of the encounter of the three main characters defines the temporal texture that constitutes the background of the story. Welles’s aesthetic program is about reinforcing the oral aspect and insisting on the sound texture.

At the image level, to the fascination of the narrator and that which is narrated as a veiled plot to conceal the temporal angst, corresponds the field of the magician and magic, the illusion of eternal life and the image in the mirror. In this way, the reflection, the mirrored, but also the transparent, the evanescent, the dissolved, the changeable, are the ways of fragile image that correspond to that powerful sound tissue.

Welles strengthens, from fiction, as he will strengthen in his television or cinematographic essays, another important figure in television: the talking man that questions the spectator in a frontal and direct way. This figure, naturalized by television, will also be important in modern cinema. For Welles, as we have seen, it founds the possibility of any work for television: the direct confrontation with the audience.

Past future

We have wandered through some experiences that reinforce the idea of a television fiction, of a television, driven by filmmakers. It has been like so throughout history. The specifics of the length, the repetition, the seriality; plus other coordinates related to television such as simultaneity, intimacy or the popular reach of the medium, have turned television into a territory of infinite possibilities to explore starting from assuming a certain poverty of the image.

Today, when television, largely, has chosen to enrich its image to defeat cinema with its own weapons, we must remember that the future of television once went through singular and extraordinary works that elaborated an aesthetic program for television fiction as a space of prolongation and renovation of cinema’s possibilities from the sources that nurtured the medium, searching a specificity, a different articulation, a way of writing the world that would use other tools and would transport the experiences in another way. The future has not been written in that way, but the works that remained were possible roads which paths remain unfathomed.

FOOTNOTES

1 / We are conscious of the vagueness of this statement as the fictious work fragments for television can be taken from many points. On another hand, a film such as The Immortal Story (Une histoire immortelle, Orson Welles, ORTF, 1968) can be considered a work of television fiction. Nevertheless, in its plan and methodology, besides of the funding source, the difference between a conception of cinema (where the film has usually been screened) and television cannot be seen.

ABSTRACT

This article explores different specific projects for television by filmmakers who work in connection with previous founding forms of TV as a hybrid medium: theater in Jean Renoir, realist novel in Maurice Pialat, televisuality in David Lynch, and verbal discourse in Orson Welles. Thus the specificities of duration, repetition and seriality, plus other televisual traits such as simultaneity, intimacy and popular appeal, turn TV into a realm of infinite possibilities based on a certain “poorness” of its images, which can be hinted in the television projects of such filmmakers.

KEYWORDS

Cinema, television, theatre, novel, radio, live, media, Renoir, Rossellini, Bergman, Pialat, Lynch, Welles.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

L’HERBIER, Marcel (1954). “Téle-Shaw” in Cahiers du Cinéma nº 31.

QUINTANA, Àngel (1995). “La televisión como instrumento para un cine de la escena” in Nosferatu nº 17-18.

MÉRIGEAU, Pascal (2003). Maurice Pialat, l’imprécateur. Paris. Grasset.

RENOIR, Jean and ROSSELLINI, Roberto (1958). “Cinéma et televisión” in France Observateur, nº 442.

RODLEY, Chris (2005). Lynch on Lynch. Londres. Faber & Faber.

ROSSELLINI, Roberto (2000). El cine revelado. Barcelona. Paidós.

SABOURAUD, Frédéric and TOUBIANA, Serge (1988). “Zappeur et cinéfile. Entretien avec Serge Daney” in Cahiers du Cinéma nº 406.

FRAN BENAVENTE

Professor and director of the degree in Audiovisual Communication at Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Fran Benavente lectures on the history of audiovisual genres and television narratives. As a film and television critic, he writes for periodicals such as Caimán / Cuadernos de Cine or Cultura/s, the cultural revue of La Vanguardia. He has published numerous academic articles and collaborated in a number of books on cinema and serial fiction.

GLÒRIA SALVADÓ

Glòria Salvadó is a professor of Audiovisual Communication at Universitat Pompeu Fabra, where she lectures on audiovisual narratives and the relations between film and television. She also lectures for Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. As a cinema and television critic, she writes for magazines such as Caimán / Cuadernos de Cine and Cultura/s, the cultural revue of La Vanguardia. She has published numerous academic articles and collaborated in a number of books on cinema and serial fiction.

Nº 7 HOW FILMMAKERS THINK TV

Editorial. How Filmmakers Think TV

Manuel Garin and Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

Cinema and television

Roberto Rossellini

Three questions about Six fois deux

Gilles Deleuze

Birth (of the image) of a Nation

Jean-Luc Godard

The viewer’s autonomy

Alexander Kluge

Cinema on television

Marguerite Duras and Serge Daney

Critical films were possible only on (or in collaboration with) television

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Medvedkin and the invention of television

Chris Marker

TV, where are you?

Jean-Louis Comolli

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Between film and television. An interview with Lodge Kerrigan

Gerard Casau and Manuel Garin

ARTICLES

Ten founding filmmakers of serial television

Jordi Balló and Xavier Pérez

Sources of youth. Memories of a past of television fiction

Fran Benavente and Glòria Salvadó

Television series by Sonimage: Audiovisual practices as theoretical inquiry

Carolina Sourdis

The televisual practices of Iván Zulueta The televisual practices of Iván Zulueta

Miguel Fernández Labayen

REVIEWS

JACOBS, Jason and PEACOCK, Steven (eds.). Television Aesthetics and Style

Raquel Crisóstomo

WITT, Michael. Jean-Luc Godard. Cinema Historian

Carolina Sourdis

BRADATAN, Costica and UNGUREANU, Camil (eds.), Religion in Contemporary European Cinema: The Postsecular Constellation

Alexandra Popartan