CINEMA ON TELEVISION

Marguerite Duras, Serge Daney

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

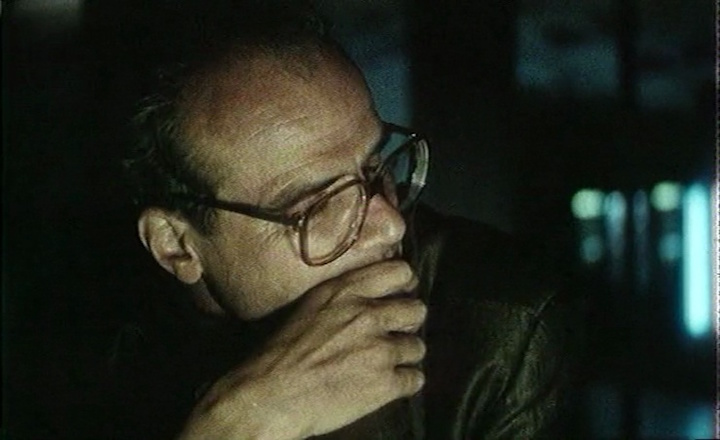

Below: Serge Daney in Jacques Rivette-Le veilleur (Claire Denis, 1990)

Marguerite Duras: Imagine that you watch a film for the first time on television.

Serge Daney: It is somehow a general matter, because I have watched and watched again a lot of films on television, or films I had not seen in a while at theatres. Television is not a media that shows an unprecedented cinema, rather the complete opposite. In fact, I constantly watch television at night, but on the other hand, I understand the perverse consternation among cinephiles. It is formidable, as far as I can tell, because it causes a more direct and effective consequence than theatres themselves before becoming deserted. What would you say about the greatness that is exhibited at theatres to someone who is willing to learn cinema?

MD: Think about Bresson, for example, when he discovered television. I could not have imagined it. For me, television is all what makes part of cinema compressed in a little space, but in a perfect quality. Think about Canal Plus, from six o’clock to five in the morning there are consecutive films, one after the other, of all genres, besides the chapters of different series and so on… And images keep that content of suspense, that purely cinematographic quality.

SD: Television, just as we understand it, is an act, and the figure of the film critic as literary is blurred, he is no longer isolated and the flux of films is so wide that television even allows watching both the part and the whole of a film.

MD: Yes, I watch cinema on TV and it is a hobby for me. It takes those long hours at night when I find it difficult to sleep. And it is perfect.

SD: What is television for you?

MD: It is marvellous. It keeps the cinematographic pure moments and that conception of suspense, of not being able to see what will happen from shot to shot.

SD: That idea of suspense means that this stirring moment through images, which is extraordinary and precious like the projector of the first cine-clubs where Charlot and Maurice Chevalier were screened, exists.

MD: Yes, but this will never happen again.

SD: Won’t it? It is more of an American tradition to transport the whole of cinema to television, but without that rather social behaviour. Think about movies such as Star Trek (Robert Wise, 1979), which allows creating a fanatic space for the film when broadcasted, and become more profitable even if its social and gathering-at-cinema aspect is lost. And it is easier to play with this kind of contents that can be watched multiple times by all the members of the family, from the very young to the adults.

MD: Actually I have abandoned myself to Canal Plus and I believe the purpose of television is not to keep me calmed and quiet, it is another one. It is purely the occupation of time in space. It has a certain vacuity and in less than an hour you get an asleep person watching. But you do not know if they are watching or not.

SD: Let’s talk about the dubbing in films.

MD: Well, if it is well synchronized and it corresponds perfectly to the image it produces a great pleasure, even more than if we had to be aware of the subtitles the whole time.

SD: And even if English is one of the most popular languages, there is always a version of the films in French. We see the gangsters, for instance, speaking in French and we find it accurate because, at the end, we distinguish dubbing from what it is not. And in this dubbing we do not discern whether the French is from one zone or another, better or worst spoken.

MD: But the thing is that we do not have the same speech. There will always be differences between people who live in the same place, like if we start talking about the different zones in the world where French is spoken.

SD: I have taken twenty years to say this, but I see that dubbing on television is one of the best encounters ever made. How can this be?

MD: It remains a mystery because the future of television is a great enigma.

SD: What do you expect from television?

MD: Well, I will keep my eyes on the perfection of the language, however it is, in that it remains so beautiful, always suggestive.

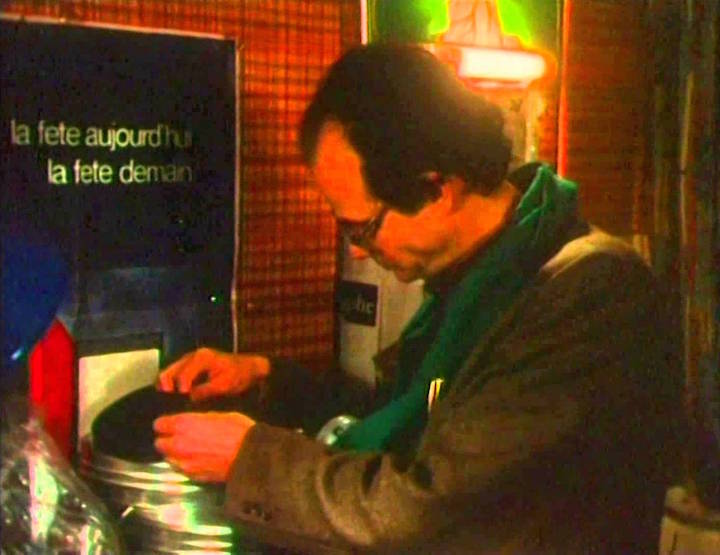

(Agatha et Les Lectures illimitées, 1981). Photo by Jean Mascolo

SD: For instance, talking about the viewers of the films, the number has been changing but you still have a very reliable audience. Why do you think this happens?

MD: Well, the number is not important. It should be rather qualifying than quantifying because if numbers had regulated cinema, a lot of films that we currently watch and find genius would not have been made.

SD: But if we talk about commercial films, it is different. The quality tends to a decline for the benefit of more elevated audiences records. But it is also easier to find certain funding.

MD: That's true, it finally tends to look like television, as it wants to imply young people as well, who are more vulnerable to this type of films. On the other hand, these films will be broadcasted later, so they reach twofold effects.

SD: It is difficult to know what to prefer, if cinema in original version with subtitles, or dubbed… Anyhow, it is difficult to know the "what", because finally there are always very good things, others less so, but currently with television we have to accept them, look back and draw some conclusions.

MD: Yes. One day, I cannot remember when, I watched on television a beautiful film. I think I have never seen a movie with that level of detail about love and with the speech so well performed. It was a unique document about cinema, and I watched it on television.

SD: American films have always had something to say in this respect. No matter how much resources are destined to a film, there are also very interesting works with great artistic value. For instance filmmakers such as Coppola, Scorsese and historical films or films with historic topics such as Platoon (Oliver Stone, 1986) end up giving a unique point of view. But there is also a huge industry behind these films about the war, the soldiers, etc. They could make a Platoon 2 without any trouble.

MD: I found Platoon very sadist, although there are things to stand out from this film. But still, the cinema that interests me the most, and that is connected with American cinema by its cultural and artistic origins, is English cinema and its sound. This language in films is so pure and marvellous.

SD: And what do you think about British pronunciation? Do you think it has an inherent dramatization according to the pronunciation itself that was already in the classics authors of Anglophone literature?

MD: Well, yes, it is a way of making things. They have one, and it is like that. On the other hand, if you start to analyse American cinema you see that Fonda, beyond having the lead role of the films, was a symbol of that American cinema in a very concrete time. His being penetrated the films themselves. This is the American phenomenon and I really love it. The same happened with John Ford, but it was different with Hitchcock since he exceeded the actors in that moment.

Below: Ingrid Bergman and Roberto Rosellini during the shooting of Stromboli, Terra de Dio (1949)

SD: But in Europe something similar happened with Rossellini and Ingrid Bergman, although both of them were determined to approach a European reality that carried certain social concerns as much in Italy as in other countries.

MD: Yes, besides it was a rather pedagogic cinema and quite apart from Hollywood, in which women became a moral object for the audience.

SD: Currently, with television, that paradigm has changed a lot. Any young actor becomes instantly a fanatic object, famous, only for standing out a little on television. And there is something dark and unknown in what these images generate in the audience.

MD: Yes, in television and the system that has been generated around it, there is something really evil and dark that makes one unable to construct that type of more lasting and interesting images that cinema did allow before. For example, something very similar happens in French cinema: the actors are actually very reserved, but the behaviour in their roles have lead the public to take them to the personal scene without being able to distinguish one thing from the other.

SD: Yes, sure. I understand that in cinema the mind-set is to experience things to the limit for the sake of the film and even for the trajectory of the actor, but at the same time it implies to be able to handle this in a certain way, considering that people all over the world believe they can mix everything at once or when the film is over. But nevertheless, cinema’s speech has always been worked on the image rather than on the sound, that is even more important than or stands outs from the image itself sometimes.

MD: It is believed that language, speech, is hardly exportable. Nevertheless it is universal. So what interests me about cinema is precisely that, the word that can be both heard and silenced.

SD: But television simplifies things. You can watch a summary or a little excerpt of a certain film and then change the channel or turn it off.

MD: Up to a certain point it happens the same with readings. Before reading a book we always want to see that little excerpt, a summary of what we will find inside, and only after this we decide whether we get on board or not. I do not think this changes with television, and it should not be detrimental to films.

SD: But in television the film looses its words or its most cinematic term. This small space that is the television cabinet is not enough for the characteristic abstraction that cinema screen allows, even if its code is present.

MD: For me cinema is to know to listen right. To be able to do so, and even if the deepness in the code continues to exist and the abstract dimension is changed or blurred, it depends on the tolerance of the audience, what they know beforehand and how they feel in that moment.

SD: Then, we are talking about leaving it all to the audience, aren’t we?

MD: Somehow we are. It is the game that television proposes: the tolerance of the audience with films. This is why I believe that at schools seeing and listening should be taught before reading. This is the key, actually: the tolerance of the audience, which already determines several production aspects.

This conversation took place within the radio program Microfilm, by Serge Daney. It was broadcasted on France Culture in April 26th, 1987.

Conversation transcribed and translated by Valentín Vía.

Nº 7 HOW FILMMAKERS THINK TV

Editorial. How Filmmakers Think TV

Manuel Garin and Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

Cinema and television

Roberto Rossellini

Three questions about Six fois deux

Gilles Deleuze

Birth (of the image) of a Nation

Jean-Luc Godard

The viewer’s autonomy

Alexander Kluge

Cinema on television

Marguerite Duras and Serge Daney

Critical films were possible only on (or in collaboration with) television

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Medvedkin and the invention of television

Chris Marker

TV, where are you?

Jean-Louis Comolli

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Between film and television. An interview with Lodge Kerrigan

Gerard Casau and Manuel Garin

ARTICLES

Ten founding filmmakers of serial television

Jordi Balló and Xavier Pérez

Sources of youth. Memories of a past of television fiction

Fran Benavente and Glòria Salvadó

Television series by Sonimage: Audiovisual practices as theoretical inquiry

Carolina Sourdis

The televisual practices of Iván Zulueta The televisual practices of Iván Zulueta

Miguel Fernández Labayen

REVIEWS

JACOBS, Jason and PEACOCK, Steven (eds.). Television Aesthetics and Style

Raquel Crisóstomo

WITT, Michael. Jean-Luc Godard. Cinema Historian

Carolina Sourdis

BRADATAN, Costica and UNGUREANU, Camil (eds.), Religion in Contemporary European Cinema: The Postsecular Constellation

Alexandra Popartan