THE TELEVISUAL PRACTICES OF IVÁN ZULUETA

Miguel Fernández Labayen

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Marta’s aunt: Are you fond of TV?

José Sirgado: I only watch the pictures

Dialogue from Arrebato (Iván Zulueta, 1979)

Introduction

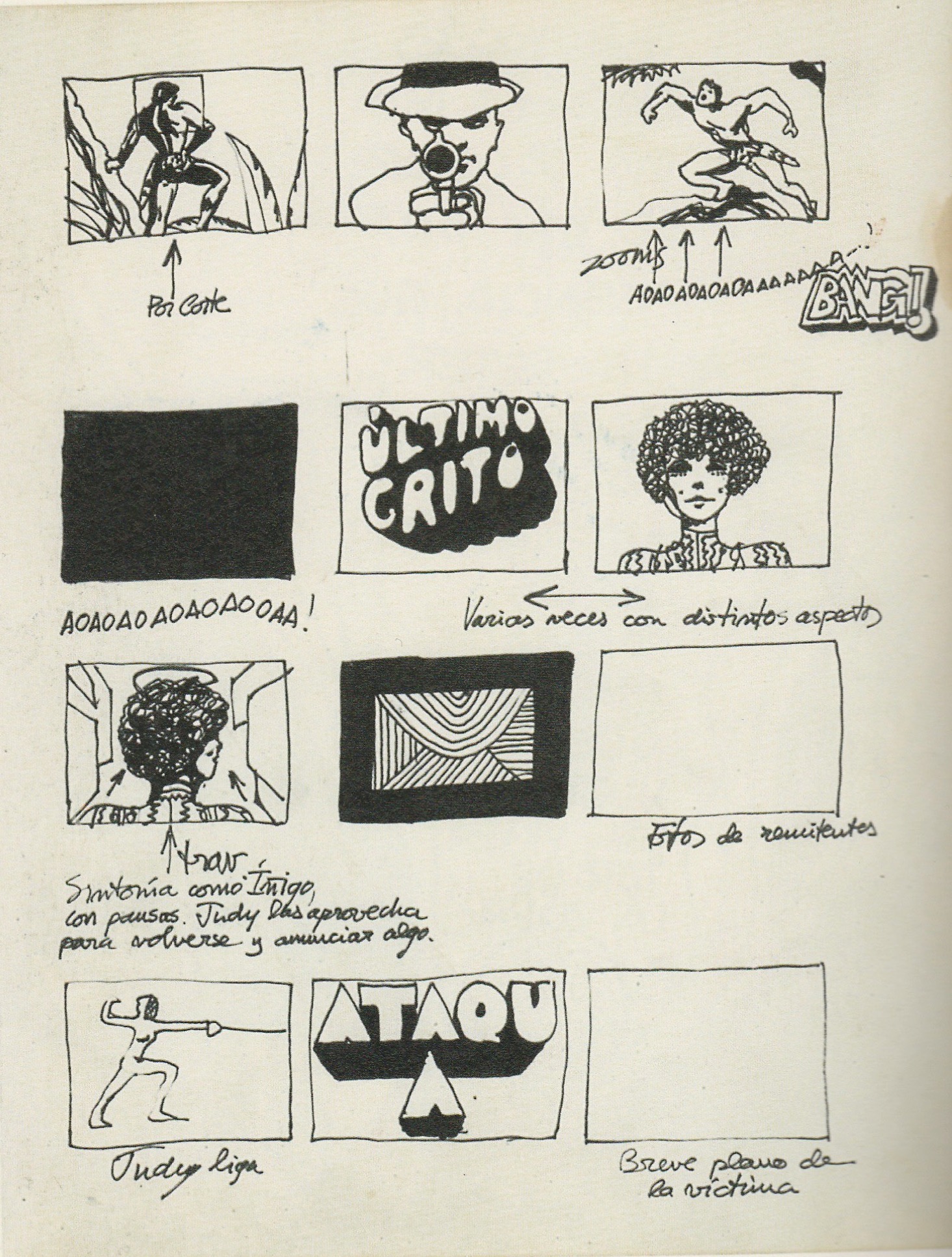

‘Various times with different shades’. That’s what can be read in a handwritten note in the storyboard of the opening credits of Último grito (TVE, 1968-1970). Those words could very well summarize Iván Zulueta’s relationship with television. On the one hand, they grasp the formal and aesthetic diversity of his collaborations for TV, which range from the creation of a cultural magazine as Último grito to the direction of one of the episodes of the fantasy serial Crónicas del mal (Ramón Gómez Redondo, TVE, 1992). On the other, the sentence plays around with notions of repetition and change, much beloved concepts in the pop culture of that time (Warhol serigraphies come to mind). Moreover, the tensions between repetition and change lie deep in the core of Zulueta’s oeuvre as a visual artist, whose theoretical inquiries on the nature of cinematic rhythm, pause and arrest blossom in Arrebato (1979) and his late series of Polaroids.

Overall, the trajectory of Zulueta is shaped by the use of TV as a modernizing entity: since his formative years as a director in Último grito, when he was still a pupil of the Escuela Oficial de Cinematografía, until the shooting of Ritesti (TVE, 1992), his last audiovisual piece. Zulueta’s work for and with television allows for a reassessment of the importance of television within film and visual studies, not only as a culturally significant agent, but also as a breeding ground for transgressive aesthetic forms. This text will explore Zulueta’s experience in television focusing on Último grito and his works of the 70’s as televisual practice, where televisual means

‘The structures of the imaginary and/or epistemological that have taken shape around television over its history […] a set of critical discourses that define and attribute properties to the medium –for instance, as one of liveness, presence, flow, coverage, or remote control’ (PARKS, 2005: 12).

It could be argued that the televisual practices of Iván Zulueta connect with the industrial modernization of Spain while embodying a certain cultural conception of what being moderno meant at the time, thus bridging the radical and elitist qualities of the avant-garde with the popular appeal of mass TV entertainment.

Consequently, this text offers an account of Zulueta’s duties as a director working within the limits of Spanish public television at the end of the 60’s, and as an experimental filmmaker in the 70’s. From that point of view, I will highlight the key role of television for any study of Zulueta’s oeuvre, not in order to antagonize cinema and TV but in order to reconsider the transmedia approach of his creative career. Under that scope, the career of the Basque artist should be understood in continuous dialogue with the growing postmodern visual culture of Spain throughout the 60’s, when filmmakers and television directors were part of a social network that included admen, visual artists, architects, graphic designers, musicians and other cultural agents. Therefore, this text is related to previous works that have studied the tensions between cinema and television in Spain during that period (CAMPORESI, 1999) as well as the forms of audiovisual and artistic experimentation in both media beyond our borders (CONNOLLY, 2014; JOSELIT, 2007; MULVEY and SEXTON, 2007; WYVER, 2007). The analysis of such connections is not rooted on a celebration of Zulueta’s televisual work based on his cinematic authorship; conversely, the goal is to open a new path to study the pleasures caused by the juxtaposition of entertainment, art and daily life originated in the second half of the XXth century (SPIGEL, 2008).

Último grito and modernity in Spain: contextual matters and historiographic issues

Último grito stands as the first professional work of Iván Zulueta. Pedro Olea, writer and director as well as former student of the Escuela Oficial de Cinematografía, who had been working in television for some time, facilitated Zulueta’s debut as director in the show. Olea defined the project –that was to be named A todo color– as a ‘weekly revue for those who want to keep up with the times’ and it included up to seven sections encompassing interviews, film reviews and reports about fashion, cinema and music (GALÁN, 1993: 32). The show, already with its final title, ended up being structured in four sections: “Ataque a”, “Reportajes”, “Cinelandia” and “33/45”, of which the former one, introduced by Nacho Artime, disappeared in the first season. The show was hosted by Judy Stephen, a Texan who had already appeared in Escala en HiFi (Fernando García de la Vega, TVE, 1961-1967), and José María Íñigo, in what became his first appearance as a television host.

In Wednesday May 22nd 1968, between 22:45 and 23:15 hours, Último grito premiered in the second channel of Televisión Española. Originally, the show came right after Tiempo para creer (Ángel García Dorronsoro, TVE, 1967-) and before Cuestión urgente (Esteve Duran, TVE, 1967-1970), which closed the UHF broadcast signal. Nevertheless, its schedule changed several times through the first season between 22:02 and 00:00 hours, even moving to other weekdays. For starters, a round of 36 episodes was broadcasted –Christmas break included– until Wednesday February 19th 1969. The show finished one year later, after a second season of nine episodes broadcasted between December 9th 1969 and January 22nd 1970, usually in the 23:45 hours time slot.

There’s one main obstacle when it comes to studyin Iván Zulueta’s work in Último grito: from a total of 45 episodes of the show that were actually broadcasted –as stated in the TV schedules of TeleRadio– only five remain available inside the archives of Televisión Española, along with a recap of almost 50 minutes that mixes excerpts of those same episodes1. Therefore, any remark about the content of the program today remains necessarily partial.

Besides, it is inexcusable to keep in mind that we are talking about a television show made collectively, as most TV productions. So on Tuesday May 22nd 1968, TeleRadio published a TV grid announcing that the premiere of Último grito was directed by Iván Zulueta and written-directed by Pedro Olea. Although Olea ceased directorial duties in the second episode, due to other film commitments, he remained close to the show. Also, contributions by other directors such as Ramón Gómez Redondo and Antonio Drove were instrumental during the show’s second season, to the extent that the former was in charge of directing several episodes and the latter created many of the sketches that still survive today (ALBERICH, 2002: 44-45). Gómez Redondo himself underlines certain key aspects about the production of Último grito: ‘the show had three directors, Zulueta, Drove and me, the system was perfect: every three-week period, one was used for prep, another one for shooting and the last for editing, so there was always a team in the works’ (FARRÉ BRUFAU, 1989: 351).

On the other hand, as the erratic programming of the show proves, it is rather clear that Último grito did not become a massive hit. The late broadcasting schedule in a weekday definitely limited its scope, not to mention the far from popular ratings of TVE’s second channel at the end of the 60’s, only two years after its creation in 19662. While the total amount of television sets in the country raised from 30.000 in 1957 to almost three millions in 1968, Último grito’s debut year, and kept augmenting until four millions and an aggregated daily audience of fifteen-million in 1970, right when the show was cancelled (RUEDA LAFFOND and CHICHARRO MERAYO, 2006: 86-92), we should keep in mind that the UHF signal would still need fifteen more years to reach the total Spanish territory and the second channel had a minority audience in its early years.

And yet, the impact of UHF in a country like Spain was huge for those sectors of the population with an interest in culture as a whole. Even more so, among the authorities of the regime there was a clear notion that TVE’s second channel would allow for newer grounds in terms of cultural and educational programs (PALACIO, 2001: 125). As Manuel Palacio has pointed out, the debuts of several former students of the Escuela Oficial de Cinematografía at TVE’s second channel, as well as the search for innovative forms among its different shows, set the ground for a Golden Age of television in Spain to blossom. Moreover, the artistic and pedagogical values of several shows broadcasted during the early years of TVE-2 are key in order to understand the relationship of a minority television like this and the quality television standard shared by most second-channel emissions all over Europe (PALACIO, 2001: 123-142). Overall, the placement of Último grito in TVE’s second channel helps us to better grasp why the work of Zulueta, Drove, Gómez Redondo and Olea wasn’t an anomaly in Francoist television, instead, it proves a connection with wider tendencies of programming and consumption generally neglected by historians.

TeleRadio, the official magazine of Televisión Española, defined the show as ‘features and stylish music in a happy, young and very in format’ (TELERADIO, 1968: 55). And no doubt, that was the show’s main logic: to be in. At that time in Spain “being in” or “staying in” meant following the latest artistic movements, being up to date with new developments in art or design, and expressing that modern way of understanding life with a casual use of English vocabulary and a touch of irony when discussing mass culture and film-music references. Consequently, Último grito fantasized with the ideal of progress that TV promised while showcasing a casual cosmopolitism.

The fact that such an internationalization, embodied in the Anglo-Saxon experiences of Zulueta and Íñigo, was only at reach for a certain cultural and economical elite that could afford to travel to London or New York and keep up with the musical and artistic scene, turned the show into something even more fascinating for the Spanish youth. As José María Íñigo remembers: ‘in mid-July and August, during the peak of summer, I would host the show wearing a scarf and a coat, just in order to upset, to draw attention, it was a way of representing a different culture, a way of saying here-we-are and this-is-our-thing’ (ÍÑIGO, 2006).

That will to épater turned Último grito into a counter-space, where the iconoclastic appeal of pop worked as an escape mechanism as well as a social and cultural trademark for the young urbanites that formed the show’s ideal audience.

On the other hand, programs like Último grito brought the television viewers closer to the growing internationalization of the country, present as well in the spread of pop music sung in English and its celebration in films such as Dame un poco de amoooor…! (José María Forqué, 1968). The international team of Último grito, with Judy Stephen, José María Íñigo and Iván Zulueta on the top, allowed for contents in which American and English pop culture were vital to construct a different type of sentimental education, a new role-modeling process for younger audiences. As Manuel Palacio has explained, ‘that is the first attempt to connect with the 60’s youth from an Anglo-Saxon cultural approach, where political struggle evolves through very different channels than those of traditional Marxism (Frank Zappa being its paradigm)’ (PALACIO, 2006: 36).

Along those lines, the show of Zulueta, Íñigo and Stephen was one among several TV initiatives in which international entertainment brought a breath of fresh air to Spanish visual culture, while making audiences familiar with international celebrities. In the 70’s, television directors like Chicho Ibáñez Serrador or Valerio Lazarov joined the ranks of Televisión Española, and by means of their shows reshaped televisual language and refurnished the cultural references of the Spanish average viewer, advocating for a certain cultural capital and a sort of transnational aesthetic sensibility (BINIMELIS, CERDÁN and FERNÁNDEZ LABAYEN, 2013). So the agenda of Último grito was significant as far as the cultural distinction of younger viewers was concerned, setting apart from the master lines of the regime; something that the press already understood when labeling it as ‘a program of true international scope’ (DEL CORRAL, 1968b: 77), an exception against the traditional classicism of first channel shows such as Estudio 1 (TVE, 1965-1985; 2000-) or Novela (TVE, 1962-1979), directed by professionals like Pilar Miró, Fernando García de la Vega or Gustavo Pérez Puig among others.

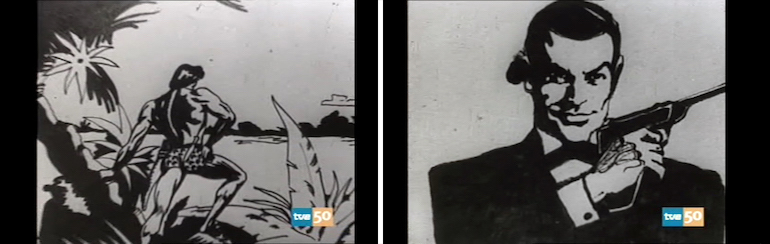

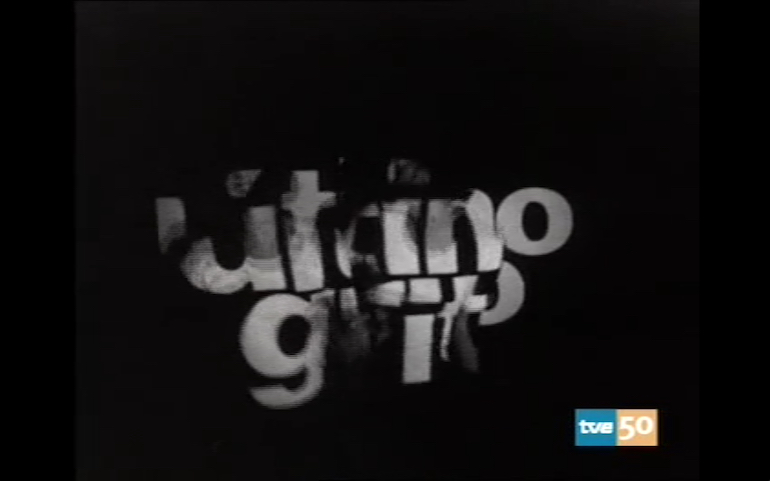

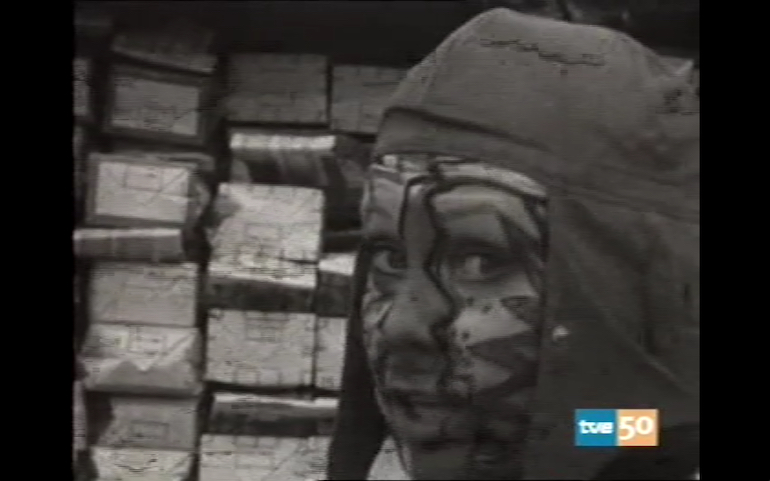

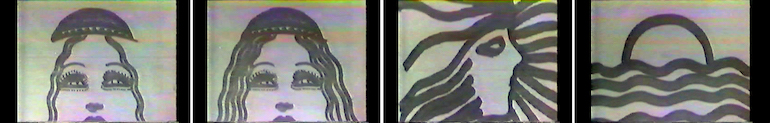

A closer look at Último grito’s content can be useful to understand Enrique del Corral’s quote3. In aesthetic terms, the use of optical effects, the intermittence of black and white backgrounds as well as the search for a psychedelic visual saturation by means of superimpositions and unconventional camera angles created an unprecedented type of show in Spain. The opening credits, designed by Zulueta, already announce an eclectic disposition and operate as a storm of cultural referents. A visual dialogue between portraits of Tarzan and Sean Connery as James Bond, while the jungle man’s scream fades with the melody of 007 interrupted by a shot, with an illustration of a comic-strip “BANG”. Frames of Barbarella follow (Roger Vadim, 1968), mixed with images of Popeye, Little Lulu and Snoopy among other cartoon idols. Such a rapid-fire succession of figures, edited in sync with Tony Newman’s “Let the good times roll” as the opening tune, ends with a frame of Lon Chaney from The Phantom of the Opera (Rupert Julian, 1925). The music sets the tone for the title credits and the entire show, a retroprojection over the bodies of two female figures who dance to the song. Finally, a montage of rock-band images closes the program’s opening credits4.

The available version of the credits is surprising for at least three reasons. First, the show is in fact proud of being fashionable, premiering images previously unknown to Spanish cultural consumers. For instance, the quote to Barbarella is ahead of its time, since Vadim’s film wasn’t released in Spain until 1974. On the other hand, the type of cultural references evoked create an eclectic juxtaposition where ironic naïf quotes of cartoon characters share time and space with the pantheon of rock music, a taste for pop icons and the cultivated reference to Chaney. Finally, the prominence of the female body and the sexy dreamy choreographies of the two girls dancing in the credits, with the title projected as body art over their skins, enhance the sex appeal of the show and connect with similar strategies deployed by Valerio Lazarov in the first channel of TVE.

The show was shot in 16 mm and ended up being structured in three main blocks: “Reportajes”, reports on trendy cultural topics (such as surf, comic books or pop art); “Cinelandia”, a revisionist approach to Hollywood’s cinema and Spanish films of the time, and “33/45”, where the latest music albums were reviewed, often using original designs by the show’s creative team to illustrate every specific song.

The reports combine an informative voice-over with explanatory images related to any given topic. On location interviews are added on, in order to offer a casual commentary on the different news. Sometimes the section includes excerpts of the show’s hosts where they make use of their unique creativity, especially by using a set of rhetoric and ironic strategies of their own, far less traditional than the norm.

“Cinelandia” also plays around that tension between information and expression. On the one hand, the classic cinephilia of the show’s directors is widely exhibited thanks to the reports on Hollywood’s iconic celebrities. On the other, that traditional approach is enriched by a set of pop references, by means of a series of movie parodies and spoofs of recently released films such as La madriguera (Carlos Saura, 1969) turned into La marrullera, directed by Santos Maura; or Winning (James Goldstone, 1969) turned into 500 Prix. The use of 16mm allowed for a type of aesthetic based on location shooting, making the best of budget constraints by referencing them in a series of self-reflective camp exercises. Parody and exaggeration are used to underline some of the existentialist ambitions of Saura’s symbolic cinema as well as other Spanish authors, or the blatant exploitation of melodrama and epics in American films.

Ultimately, Último grito became an appealing show thanks to its innovative design and the creativity of Zulueta and the rest of the directors working in the program. In section “33/45”, for instance, with a limited budget and without being able to reach directly any of the music bands mentioned in the show, the filmmakers had to generate their own graphic material and footage to accompany those band’s music.

Therefore, the most common strategies were the reappropriation of previously existing footage from live concerts and the collage of still images of each group, from Frank Zappa & The Mothers of Invention to Long John Baldry, Carla Thomas or T Rex. Other times, the show would create new footage ex novo, by recording images on location (as in the shooting of Ismael’s “La Tarara” by Pedro Olea) or by generating animated stop motion pictures.

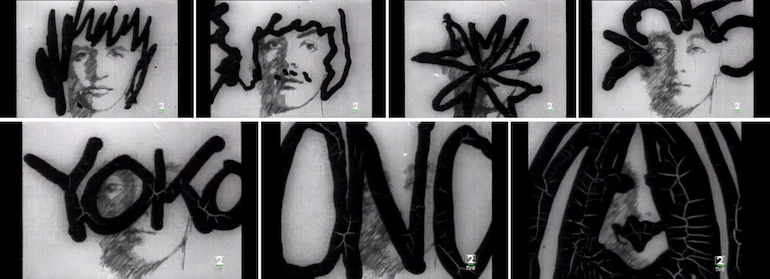

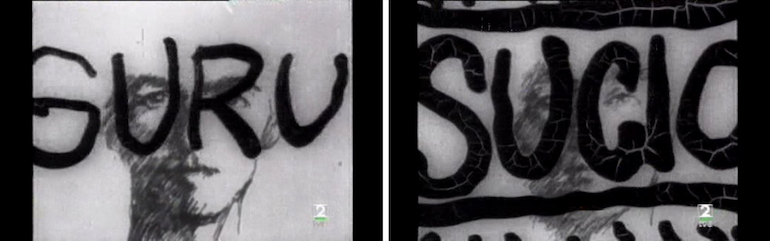

On such occasions, Zulueta’s inventiveness and formal training as a painter, designer and filmmaker was key in order to explore that fertile juxtaposition between animation and music. Zulueta created a series of takes of pop songs of the period, from which remain available his visions of The Beatles’ “Something” and “Get Back”. The visual strategies are similar in both cases: Zulueta tries out a multiplication of curves and dots painted on the film itself, which appear on screen to complete footage of a sunset on the beach or oriental-style portraits. Furthermore, in the case of “Get Back”, Zulueta super-imposes such modulations over a series of portraits of the four Beatles in their early years, thus following the rhythm of the song to add a number of written messages (Apple, Strawberry Fields Forever, Let It Be) over the musician’s faces, so their silhouettes are stretched and supplemented with all sorts of props like sunglasses, beards, moustaches or even Yoko Onos in Lennon’s case. Zulueta tames the Fab Four for a Spanish audience while he explores the metamorphic possibilities of animation to create comical nuances and to stress the Beatles’ style changes and appearance. For instance, he introduces the four Liverpool musicians using brief title cards that blink for less than a second. From right to left, the sentence “Pablito es limpio” is suddenly transformed into the pun “Pablito es impío”. The piece plays around the band’s imagery with a high degree of self-conscious irony, mixing appraisal and distance, as proven in the later title cards devoted to George Harrison (“Jorge es guru”) and John Lennon (‘Juanito es sucio, muy sucio, ¡sí!’). At the same time, the piece stands as a useful example to understand the controversy on what was considered acceptable in terms of musical representation and foster debate between abstraction and figuration, art and mass consumption.

As Carlos F. Heredero (1989) and Manuel Palacio (2006) have noted, the final result connects with Norman McLaren’s experiments and the practice of visual music so dear to avant-garde cinema. The connection with McLaren is double-layered, since on the one hand, and beyond the shared Basque origin underlined by Heredero when he mentions other Spanish experimental animators of that time (José Antonio Sistiaga and Rafael Ruiz Balerdi), it confirms the transnational connection of those artists, because the three of them had a considerable international experience thanks to their travels and therefore acted as mediators between foreign innovations and their late arrival to Spain. On the other hand, as William Moritz pointed out, Norman McLaren’s career stands as a challenge to the modernist experimental tradition (MORITZ, 1997). His stylistic eclecticism and his interest in working with anthropomorphic forms placed his oeuvre in a sort of no man’s land, hardly embraceable by the followers of neither abstract cinema nor absolute film. That’s why Moritz labels McLaren as a post-modernist, something that could very well be said of Zulueta’s own career.

In the case of his work for Último grito and the animation of “Get Back”, it is worth underlining his refusal both of the abstract tradition (with the quintessential Ere erera baleibu icik subua aruaren painted by Sistiaga in 1970) and the figurative one (exemplified by the 1971 Homenaje a Tarzán by Rafael Ruiz Balerdi). So the boldness of Zulueta’s piece praised by Carlos F. Heredero shouldn’t be used to contrast the artistic value of cinema against television during Franco’s dictatorship, but to suggest a different genealogy, a transnational pop visual culture the integration of which in the Spanish public sphere was possible thanks to the connections between filmmakers, designers, photographers, visual artists, musicians, architects and, also, television directors and producers.

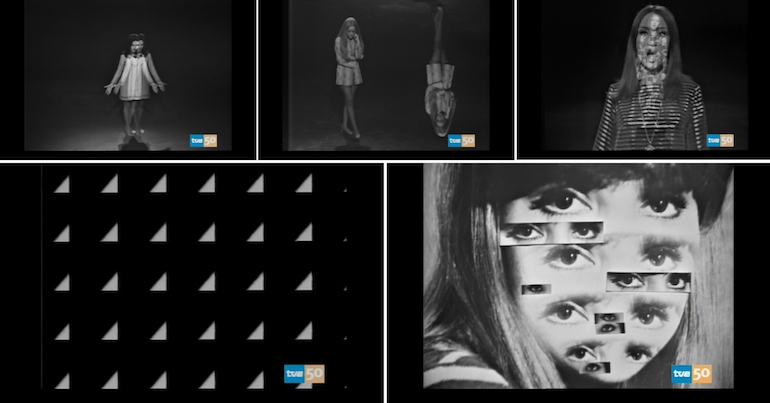

In that context, Zulueta’s work for Último grito stands in a hybrid territory between, let’s say, the proposals of the abovementioned Norman McLaren and the experiments of Valerio Lazarov, who came to Televisión Española precisely in the same year of Último grito’s original release, 1968. It is worth mentioning that both McLaren and Lazarov were part of Televisión Española’s programming in 1968. So, on Saturday September 14th 1968, curious viewers could enjoy a 90-minute special devoted to McLaren at 22:30 in the show Cine-Club. As far as Lazarov is concerned, his 1968 debut Nada se destruye, todo se transforma was a musical program with live performances of female singers, where abstraction and all sorts of optical effects were exploited in order to create an avant-garde imagery and offer dynamic solutions to the rhtyhm of pop songs. Although Lazarov’s approach arguably diluted the visual tour-de-forces of avant-garde cinema, deactivating their counter-cultural strength, it is worth noting that even the first channel of Televisión Española participated in spreading a new aesthetic which became dominant in television. Mr. Zoom, the nickname later applied to Lazarov, popularized the same style that Zulueta linked to counterculture by using it to ironically mock the devotion of Real Madrid fans. Both Zulueta and Lazarov should then be considered as catalyzing-agents of a Spanish (post)modernity that, in spite of remaining a minority in the case of Zulueta, proved to be instrumental towards aesthetic and cultural regeneration in Spain.

Be that as it may, the show had a warm reception among critics such as Enrique del Corral, who praised the release of Último grito in his television column in ABC:

‘The great spectrum of “new youth” was abandoned by Televisión Española. At most they would get music, as if music was the only effective tranquilizer for their legitimate concerns. Because that new youth has concerns. Deep ones. Now Televisión Española 2 has started a show tailored for the tastes and concerns of those young audiences. Congratulations. What I saw seemed agile, lively, modern. Finally, modern! Iván Zulueta directs a script by Pedro Olea; a nimble script, very straight and televisual, that Zulueta translated into informative and pertinent images, well edited by Luis Peláez […] “Moncho Street” with its drugstores and its posters, the music, the vibe, the happiness of that emerging youth, everything that matters was there in Último grito, which from starters, grabs attention. And that’s something… The agility and novelty of the show’s host, Judy Stephen; the boldness of the questions and the sincerity of the answers of the young interviewees; everything in Último grito breaths coolness, nerve, absence of clichés and conventionalisms. Let’s hope that the fruitful findings of that first show will blossom week after week, and the growing mass of “new” youngsters finds in Televisión Española the space they lacked and so much deserved’ (DEL CORRAL, 1968a: 83).

Del Corral became a fearless advocate of the show. It is worth recovering another of his reviews, this time written on November 24th 1968 (that is, with the show already well established) to shed some light on the cliché about the reception of certain programs in conservative media such as the newspaper ABC:

‘Último grito is the most thorough, enjoyable, efficient and bright expression of modern television in Televisión Española. From the marking system, which could be an example of montage and graphic intention, until the goodbye section, Último grito is a roller coaster of dynamism, joy and excitement, and most of all, a show full of nuances that has been improving itself more and more’ (DEL CORRAL, 1968c: 71).

The arrival in Spain of what Frederic Jameson called the cultural logic of late capitalism that identifies postmodernity as a historical process, hast a lot to do with the spread of media messages in shows like Último grito. Over the years, Último grito has become an example of progressive visions related to Anglo-Saxon popular culture. The mixture of psychedelia, youth culture and fashion stresses the tensions between the official identity based on traditional National-Catholicism and an open mind to the influence of foreign cultural affairs. From the type of music bands featured in every program to the aesthetic of each section, where the editing, lightning, art design and mise en scène all transmitted values clearly opposed to those of the traditional regime as far as their goals and their way to address the audience. Similar to what happened in other countries like the UK, those apparently harmless music shows would end up becoming key in order to grasp the national struggles of cultural identity and aesthetic canons, even more so in such an airtight environment as Spain (SEXTON, 2007). On the other hand, Zulueta himself would develop a fruitful relationship with the perceptual distortions of psychedelia, the use of hallucinogens and visual experimentation in short films like A Mal Gam A (1976), where the noisy and symphonic ending of the Beatles’ “A day in the life” finds a visual equivalent in a series of fast motion shots of San Sebastián’s La Concha’s bay and Paseo Nuevo, layered with innumerable visions of other people and objects, all in fast motion, thanks to Zulueta’s use of the camera.

In the context of such audiovisual experiments, Zulueta would later talk about certain problems with censorship. Specifically, in an interview with Juan Bufill, the artist recalls how TVE’s next assignment after Último grito ended up being cancelled:

‘They asked me to illustrate songs of the top radio-charts, one per week. I didn’t make it past the first one (“Ride like a swan” by T. Rex) because, according to them, the result was “drug-like” or something like that. All because of a close shot of a girl with her eyes closed and a steady attitude, over whom shiny and watery images were projected…’ (BUFILL, 1980: 41).

The acceptance of such proposals within Spanish television had certain boundaries, ambiguous ones, which fluctuated between the tolerance of a certain rule-breaking aesthetic and the head-on refusal of the countercultural implications of such an aesthetic.

Conclusions: the presence of television in the cinematic work of Zulueta

Último grito was ultimately cancelled in early 1970. Zulueta used the show as a launch pad for his first feature film Un, dos, tres… al escondite inglés (1969). The program had worked visually as a sort of window display, linked to a guerrilla mode of production that allowed testing the possibilities of aesthetic experimentation and the viability of certain cultural products before releasing them. Viewers like José Luis Borau, former teacher of Zulueta at the Escuela Oficial de Cinematografía and producer of Un, dos, tres… al escondite inglés, were pleasantly surprised. In Zulueta’s words: ‘I remember that Borau found the style of Último grito very modern, young, pop and cheap. He intended to make the best of José María Íñigo’s ability to connect with trendy audiences in order to market the film (Un, dos, tres…) to those same audiences in a new marketing strategy’ (HEREDERO, 1989: 92). After all, as Zulueta himself recalls, Último grito was ‘an extraordinary useful school of images’ (HEREDERO, 1989: 136).

The televisual motif became a constant in the work of Zulueta after Último grito. Of course, television holds a major role in Un, dos, tres…, the main plot of which focuses on a boycott of the Eurovision contest. Moreover, the television set in a wide sense (as furniture and as disseminating screen) has a significant presence in short films like Kinkón (1971), Frank Stein (1972), Masaje (1972), Te veo (1973) and Aquarium (1975), or in Arrebato (1979). Therefore, after his formative years in television, it is interesting to observe how Zulueta continued to explore the relationship with TV in his cinematic practice from another perspective, the aesthetic correspondences with avant-garde cinema of which have been carefully underlined by Alberte Pagán (2006). The role of Zulueta as user and re-producer of television images in his films during the 70’s rises important questions about the materiality of film and television images as well as about the socio-technological dimensions of television as a medium, in the line of previous research carried out within television studies (McCARTHY, 2001).

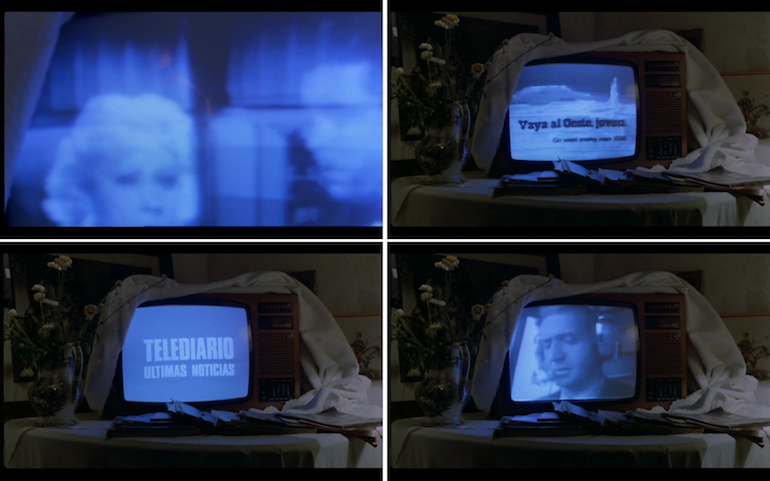

Zulueta used television in his films during the 70’s in two main ways: as a social and aesthetic escape mechanism, but also as an object capable of abducting the mind and the boy of anyone watching in front of the screen. In the first case, Zulueta works on the reappropriation of television images. Thanks to the use of re-shooting techniques, TV becomes not only an object of transmission but also a space of desire and breakout, as seen in the revivals of classical Hollywood films in Kinkón, Frank Stein and Arrebato, the acceleration of a Día de la Victoria television coverage in Masaje, or the daily shutdown of the broadcast signal in Arrebato, during the first image time-continuum break due to the encounter of Pedro and José, the film’s protagonists, when only the arrest a dizzy flux orchestrated by Zulueta make it possible to understand what’s going on. Those interferences connect with certain video art practices of the 60’s, obsessed with decomposing the television signal. Furthermore, they can be traced back to a genealogy of ‘electronic noise’ where the double-layered images and the ghosts created by such distortions are part of the everyday consumption of electronic media, thus generating fantastic visions of the medium as an entity capable of communicating with other worlds (SCONCE, 2007).

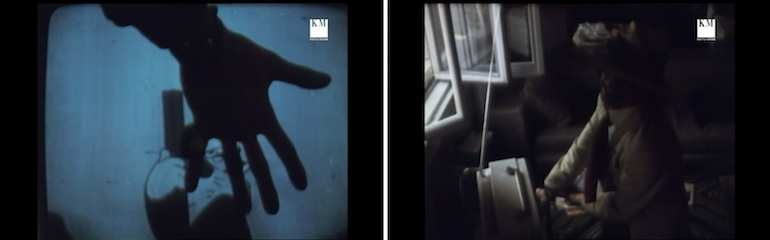

In the second case, re-shooting techniques are substituted by the direct, eerie presence of television as a screen. That option becomes material in a graphic form in Aquarium, where a bored Will More ends up literally hooked to the television monitor, which shows WB cartoons and captures the hand of the protagonist, incapable of removing himself from the screen, victim of an embodied frenzy.

In both cases lies a fundamental tension between the possibilities to alter the flux of images and the autonomy of the television set as an entity capable of transforming the viewer’s physical willingness. Belén Vidal has described some of those approaches by Zulueta as traces of a ‘possessive spectator’, following the categories proposed by Laura Mulvey in her texts on cinephilia. According to Vidal, the obsession of Arrebato’s characters with rhythm, present as well in short films like Kinkón or even –as seen at the beginning of this article– in his televisual practices, point out ‘a quest for control over the cinephilic experience’ (VIDAL, 2012). The concept of a ‘possessive spectator’, obsessed with specific moments of films –sequences, shots or frames as meaningful entities– that expand towards the temporality of the spectator, would be further enriched with the concept of ‘pensive spectator’, initially theorized by Raymond Bellour and readapted by Laura Mulvey as that viewer who, thanks to technology, can freeze the cinematic image, stop it and think about it (BELLOUR, 1987; MULVEY, 2006). Thus Zulueta would exemplify a sort of halfway spectator in-between those two models, driven by a cinephilic fetishism but also by a clear awareness of the tensions between the pause and the flux of images.

I find it appealing to link those approaches to the type of film spectator that Zulueta would represent in the 70’s with the theoretical perspectives of television as a traditional medium. In that context, the work of Mimi White on the concept of televisual fluxes explains how ‘flow represents the mediations between television technology (the flow of the broadcast signal), institutional terms of programming, and, ultimately of most significance, television textuality and viewer experience thereof’ (WHITE, 2001: 2). Although it seems rather troubling to think of Spanish television of the 70’s in terms of flow (the broadcast did not cover 24 straight hours, only two channels existed, etc.), the cinematic works of Zulueta during that period insistently draw upon television as a source of images, something almost neglected in the existing literature on the Basque director. After all, one of the founding grounds of Zulueta’s movies in the 70’s is the use of the television screen as a fountain of images, which go through a mediated process by means of their exhibition in the television set and their manipulation by the filmmaker. In those movies a distortion of the time-space continuum is possible thanks to television images, which Zulueta uses in order to carry the viewer away into a realm of fascination and alienation that ultimately poses a challenge: how to think about the material aspects of film and television both in terms of their reception and their inner belonging to a cultural history.

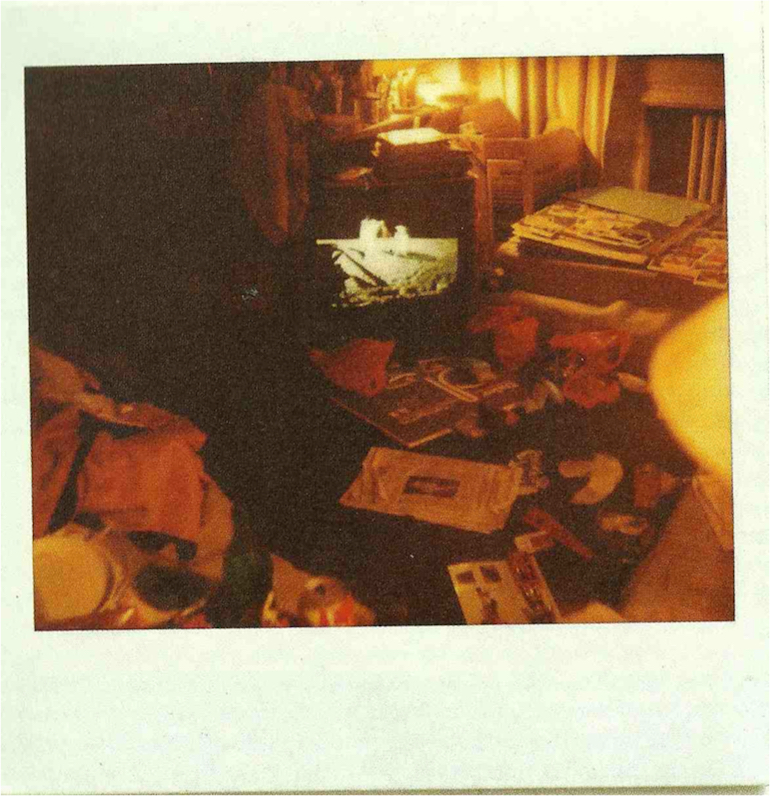

Therefore, it is only natural that in some of the Polaroids of his last years, television remains alive (switched on) and surrounded by tones of garbage. As a weird door to another dimension, Zulueta captures in those images the imbalance between experimentation and cathodic signal so intimate to his career as a whole. Television, as well as other referents explored in Zulueta’s Polaroids to express a fascination with images (trading cards, comic books, photos), becomes a remembrance of the durability of popular culture, the last thing standing in this apocalyptic photographs, the only thing capable of connecting the already retired and cloistered-away filmmaker with the rest of the world. The ‘phantom of television in the avant-garde machine’, as Paul Arthur expressed in an important essay published in 1987 on Millenium Film Journal, had the potential to become a strong ally in the battle of experimental cinema against commercial cinema (ARTHUR, 2005: 90-91)5. In that crossroad of television and experimental film, Arthur underlined ‘an attitude concerning the availability of popular entertainment, or rather its languages’ (ARTHUR, 2005: 75) as the most important trait of American experimental filmmakers in the 80’s.

Iván Zulueta’s work for and with television becomes then a vindication of the entertainment flow tied to TV. In his films, the medium becomes a physical presence, something that, according to the filmmaker’s obsession with the rapport between cinematic pause and rhythm, never ceases to be. In Zulueta’s hands, television becomes a catalyst of thoughts, visions and experiences. In an alienated and decomposing world, TV keeps a central role as the archive of popular culture, especially Anglo-Saxon popular culture, represented in some of the Polaroids by no less than the arrival of men to the surface of the moon. Once more, television becomes a sinister medium out of control, capable of activating the past independently and representing it as an anachronic pop myth. To sum up, the televisual practices of Zulueta juxtapose his interest on contemporary art, visual culture of the XXst century and daily life as possibilities of self-fulfillment. Under his wing, television becomes the true objet trouvé of experimental art: a medium not only to be taken advantage of, but to be transformed into the real agent and the ultimate subject of contemporary histories of audiovisual experimentation.

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article was possible thanks to the help of Adela Hervá, from the Documental Archive of TVE, and Raúl Pedraz, whose help in the documentation process of Último grito has been instrumental. Pedro Olea was kind enough to answer to my questions and share his memories about the show. Manuel Palacio, Josetxo Cerdán, Miguel Zozaya and Antón López have also been key for reconstructing the puzzle of Último grito.

FOOTNOTES

1 / The abovementioned recap is available for free at RTVE’s website: http://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/programas-y-concursos-en-el-archivo-de-rtve/ultimo-grito-recopilacion/1829851/. It is also possible to watch one complete episode that TVE-50 broadcasted during the fifty-anniversary celebrations of the channel. That episode was originally broadcasted in TVE-2 on a Tuesday, December 30th 1969, between 23:45 and 00:15 hours, and can be browsed in: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SI-pS8k74k8

2 / In a review of Último grito, del Corral explained: ‘the ratings of Último Grito must be scarce because of the temporal coincidence with The Avengers (ITV, 1961-1969) at the VHF channel’ (DEL CORRAL, 1968c: 71).

3 / Enrique del Enrique del Corral, critic of the newspaper ABC, was –among other things– the person who, according to Valerio Lazarov, introduced him to Juan José Rosón and Adolfo Suárez, both TVE top executives in 1966 (CORTELL HUOT SORDOT y PALACIO, 2006: 39). Later on, that meeting proved to be instrumental towards Lazarov’s arrival to Spain.

4 / In an original interview with Pedro Olea in February 13th 2013, the writer explained how the opening credits changed throughout time, so the ones available now at the archives of TVE are slightly different to the ones broadcasted in the first episodes. For instance, the single “Let the good times roll” that works as title song in the available version of Último grito was released in January 28th 1968, and by that time, the show had already been on for more than a month. On the other hand, as Diego Galán points out, among the final sketches of the project presented by Olea to TVE there was a mention to a title ‘that could be El último grito, preceded by a drawing of Tarzan, in zoom, and the sound of his unmistakable scream (and a shot)’ (GALÁN, 1993: 32).

5 / The original article is ARTHUR, Paul (1987). The Last of the Last Machine? Avant-Garde Film Since 1966. Millennium Film Journal 15/16/17 (Fall-Winter 1986-87), pages 69-93. It is hereby quoted according to its re-edition in ARTHUR, 2005.

ABSTRACT

This article explores the liaisons of Iván Zulueta with television. The first part focuses on his work for the TV program Último grito (Pedro Olea, Iván Zulueta y Ramón Gómez Redondo, TVE, 1968-1970), researching primary and secondary sources from a historiographic standpoint in order to study the context in which this musical show was produced, while linking it with various cultural synergies of its time. Último grito is therefore studied both as a key example of national television and as a juxtaposition of international cultural influences. The last part of the article studies the role of television in the cinematic works of Zulueta throughout the 70’s. Thus the goal of this research is to problematize canonic separations between TV and cinema as mediums, focusing on the trajectory of Zulueta as an example of the growth of Spanish audiovisual culture. A culture in which design, music videos and advertisement merged with experimental cinema and television entertainment, giving birth to a complex net of aesthetic, economic and cultural correspondences.

KEYWORDS

Iván Zulueta, Ramón Gómez Redondo, Pedro Olea, Valerio Lazarov, Último grito, Televisión Española, experimental television, youth cultures, experimental cinema.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ALBERICH, Ferran (2002). Antonio Drove. La razón del sueño. Alcalá de Henares: Festival de Alcalá de Henares.

ARTHUR, Paul (2005). A Line of Sight. American Avant-Garde Film since 1965. Minneapolis. University of Minnesota Press, pp. 74-91.

BELLOUR, Raymond (1987). The Pensive Spectator, Wide Angle, vol. 9. 1, pp. 6-10.

BINIMELIS, Mar; CERDÁN, Josetxo y FERNÁNDEZ LABAYEN, Miguel (2013). From Puppets to Puppeteers: Modernising Spain through Entertainment Television.

GODDARD, Peter (ed.), Popular Television in Authoritarian Europe (pp. 36-52). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

BORAU, José Luis (productor) y ZULUETA, Iván (director). (1969). Un, dos, tres… al escondite inglés. España: El Imán.

BUFILL, Juan (1980). Entrevista con Iván Zulueta. Dirigido por…, n. 75, Agosto/Septiembre, pp. 38-41.

CAMPORESI, Valeria (1999). Imágenes de la televisión en el cine español de los sesenta. Fragmentos de una historia de la representación. Archivos de la Filmoteca, n. 32, pp. 149-162.

CONNOLLY, Maeve (2014). TV Museum. Bristol. Intellect.

CORTELL HUOT SORDOT, Guido y PALACIO, Manuel (2006). El Irreal Madrid.

PALACIO, Manuel (ed.), Las cosas que hemos visto. 50 años y más de TVE (pp. 38-39). Madrid: IRTVE.

DE LAURENTIIS, Dino (productor) y VADIM, Roger (director). (1968). Barbarella. Italia: Dino de Laurentiis Cinematografica.

DEL CORRAL, Enrique (1968a). Juventud. ABC, 26 de mayo, p. 83.

DEL CORRAL, Enrique (1968b). Último grito. ABC, 23 de junio, p. 77.

DEL CORRAL, Enrique (1968c). «IN». ABC, 24 de noviembre, p. 71.

FARRÉ BRUFAU, María Soledad (1989). La Escuela de Argüelles. Una aportación al cine español. Tesis doctoral inédita. Universidad de Salamanca, 531 páginas.

FOREMAN, John (productor) y GOLDSTONE, James (director). (1969). Winning. USA: Universal.

GALÁN, Diego (1993). Del Parque de juegos a Un mundo diferente. ANGULO, Jesús; HEREDERO, Carlos F. y REBORDINOS, José Luis (eds.), Un cineasta llamado Pedro Olea (pp. 27-36). Donostia: Filmoteca Vasca.

GARCÍA DE LA VEGA, Fernando (1961-1967). Escala en HiFi. España: TVE.

GÓMEZ REDONDO, Ramón (1992). Crónicas del mal. España: Mabuse para TVE.

HEREDERO, Carlos F. (1989). Iván Zulueta. La vanguardia frente al espejo. Alcalá de Henares. Festival de Cine de Alcalá de Henares.

ÍÑIGO, José María (2006). Programa especial 50 años de TVE: José María Íñigo. España: TVE.

JOSELIT, David (2007). Feedback: Television Against Democracy. Cambridge, MA. MIT Press.

LAEMMLE, Carl (productor) y JULIAN, Rupert (director). (1925). The Phantom of the Opera. USA: Universal Pictures.

McCARTHY, Anna (2001). From Screen to Site: Television’s Material Culture, and Its Place. October, n. 98, pp. 93-111.

MORITZ, William (1997). Norman McLaren and Jules Engel: Post-modernists.

PILLING, Jayne (ed.), A reader in animation studies (pp. 104-111). Sydney: John Libbey.

MULVEY, Laura (2006). Death 24x a Second. Stillness and the Moving Image. London. Reaktion Books.

OLEA, Pedro; ZULUETA, Iván y GÓMEZ REDONDO, Ramón (1968-1970). Último grito. España: TVE.

PAGÁN, Alberte (2006). Residuos experimentales en Arrebato. CUETO, Roberto (ed.). Arrebato… 25 años después (pp. 113-140). Valencia: Filmoteca de Valencia.

PALACIO, Manuel (2001). Historia de la televisión en España. Barcelona. Gedisa.

PALACIO, Manuel (2006). Último Grito. PALACIO, Manuel (ed.), Las cosas que hemos visto. 50 años y más de TVE (p. 36). Madrid: IRTVE.

PARKS, Lisa (2005). Cultures in orbit: satellites and the televisual. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

QUEREJETA, Elías (productor) y SAURA, Carlos (director). (1969). La madriguera. España: Elías Querejeta P. C.

RUEDA LAFFOND, José Carlos y CHICHARRO MERAYO, María del Mar (2006). La televisión en España (1956-2006). Política, consumo y cultura televisiva. Madrid. Fragua.

SCONCE, Jeffrey (2007). Haunted Media. Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television. Durham. Duke University Press.

SEXTON, Jamie (2007). From art to avant-garde? Television, formalism and the arts documentary in 1960s Britain. MULVEY, Laura y SEXTON, Jamie (eds.), Experimental British Television (pp. 88-105). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

SPIGEL, Lynn (2008). TV by Design: Modern Art and the Rise of Network Television. Chicago. University of Chicago Press.

TELERADIO (1968). Programas TVE. TeleRadio n. 543, p. 55.

VIDAL, Belén (2012). Cinephilia and the lost moment: Arrebato (Iván Zulueta, 1979) in/out the Spanish transition. Ponencia inédita presentada en el Congreso Internacional Hispanic Cinemas: En Transición, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, 7-9 de noviembre.

WHITE, Mimi (2001). Flows and other close encounters with television. Fecha de consulta: 24 de septiembre de 2015. Retrieved from http://cmsw.mit.edu/mit2/Abstracts/MimiWhite.pdf

WYVER, John (2007). Vision on. Film, television and the arts in Britain. London. Wallflower.

MIGUEL FERNÁNDEZ LABAYEN

Visiting professor at the Department of Journalism and Audiovisual Communication of Carlos III University in Madrid, and member of the research group TECMERIN. His work on experimental film, documentary and transnational cinema has been published in academic journals such as Studies in European Cinema, Transnational Cinemas or Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies and in edited volumes such as Sampling Media (Oxford University Press) or No se está quieto. Nuevas formas documentales en el audiovisual hispánico (Iberoamericana/Vervuert, 2015).

Nº 7 HOW FILMMAKERS THINK TV

Editorial. How Filmmakers Think TV

Manuel Garin and Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

Cinema and television

Roberto Rossellini

Three questions about Six fois deux

Gilles Deleuze

Birth (of the image) of a Nation

Jean-Luc Godard

The viewer’s autonomy

Alexander Kluge

Cinema on television

Marguerite Duras and Serge Daney

Critical films were possible only on (or in collaboration with) television

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Medvedkin and the invention of television

Chris Marker

TV, where are you?

Jean-Louis Comolli

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Between film and television. An interview with Lodge Kerrigan

Gerard Casau and Manuel Garin

ARTICLES

Ten founding filmmakers of serial television

Jordi Balló and Xavier Pérez

Sources of youth. Memories of a past of television fiction

Fran Benavente and Glòria Salvadó

Television series by Sonimage: Audiovisual practices as theoretical inquiry

Carolina Sourdis

The televisual practices of Iván Zulueta The televisual practices of Iván Zulueta

Miguel Fernández Labayen

REVIEWS

JACOBS, Jason and PEACOCK, Steven (eds.). Television Aesthetics and Style

Raquel Crisóstomo

WITT, Michael. Jean-Luc Godard. Cinema Historian

Carolina Sourdis

BRADATAN, Costica and UNGUREANU, Camil (eds.), Religion in Contemporary European Cinema: The Postsecular Constellation

Alexandra Popartan