CRITICAL FILMS WERE POSSIBLE ONLY ON (OR IN COLLABORATION WITH) TELEVISION

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

Two fundamentally different narrative styles

'It’s a complicated project: a television series that runs thirteen and a half hours and–with another cast and a different format–a film. It’s an attempt to film the novel in two fundamentally different narrative styles […] The television series is an attempt to encourage the viewer to read, even though he’s offered visual gratification. The film works entirely different: first of all, it narrates a story in concentrated form, which achieves its effect only retroactively, when the moviegoer’s consciousness and imagination kick in. You might say I’ve stuck close to the book. You might just as well say I’ve made some crucial changes. In favor of the women, I should point out. In Döblin the women are narrated with considerably less specific identity than the men. I’ve tried, to the extent it was at all possible within this narrative framework, to describe the women as just as valuable as the men. That’s one very definite change from Döblin.'

If you have three hours rather than fifteen, you have to tell the story differently

'That’s a story in itself. Separately from the television screenplay, which is about three thousand pages, I wrote a special version for the cinema. Because I think if you have three hours rather than fifteen, you have to tell the story differently. That’s why I’m opposed to the idea of taking what we’ve already filmed and cutting it down to get this other version; the shooting would have been done differently, with different dynamics. But the screenplay exists, and some day, when the legal situation with regard to this work is more favorable, I’ll do the film, that’s certain. And it doesn’t bother me a bit that there already is a film and my television series–I don’t give a damn. It didn’t bother me with Effi Briest (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1974) at the time, either. I mean, if a film’s good, it has a strength all its own.'

Series-dramaturgy and cliffhangers

'The series will run fifteen hours. We spent 150 days shooting. You can’t just stop and start at random. That’s no good. But Döblin already had his novel divided into ten parts with main chapters, subchapters, what have you. And because of his collage technique it isn’t particularly hard to divide the story cinematically into chapters. You could also have taken and found entirely different points that would have served as beginnings and endings. There are many possibilities. It isn’t’ that it doesn’t have beginnings and endings, but it isn’t made according to Durbridge dramaturgy, either. So it doesn’t stop with a suspenseful situation that’ll make people tune in for the next segment to find out how the story continues. That I certainly don’t want.'

Television and shock, watching with less hostility

'I myself would prefer it if the moviegoer watched the movie with less hostility and with more opportunity to be conscious of what’s taking place before his eyes and what it can mean to him personally; that’s better than if he’s shocked into rejecting the whole thing at first sight, no matter how the shock may later work in his subconscious to achieve a positive effect. That can happen, too. But with a television series it’s like this: if the viewers are shocked, they’ll stop watching. Then we’ve gained nothing. I’d rather have them watch and at least come away with the idea of the story that’s being told–and why it should be told.'

The responsibility of cinema, the responsibility of television

'I’ve always said you have a different kind of responsibility. With a movie I would argue much more for shock effects, because I agree with Kracauer when he says that when the lights go out in the movie theaters it’s as if a dream were beginning: in other words, that a movie works through the subconscious. The movie version I’ve written really is entirely different. It’s not only not nearly so epic in style, but also not nearly so positive in its portrayal of Franz Biberkopf; rather it underscores the contradictions and the craziness of the character more than the television version. Here it’s more that people will understand it and it won’t scare them away, that they can grasp it directly while watching it. To consider the audience you’re working for is as legitimate, I believe, as it used to be, say ten years ago. People say, all right, the television viewers are people who’re sitting at home while something comes into their living room… And there are incredibly many of them, that’s another factor, unbelievably many, far more than at the movies. And I have a different mission with them […] You can see that from many films I’ve made. And specifically from the films I actually financed entirely on my own and without any public monies, like In a Year of Thirteen Moons (In einem Jahr mit 13 Monden, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1978) or The Third Generation (Die Dritte Generation, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1979). They’re much more uncompromising; I wouldn’t have made them for television. I tell myself that someone who goes to the movies pretty much knows what awaits him. So I can demand more effort of him. Do you understand? And I can also expect him to get more pleasure out of the effort. The argument that used to be cited, that the viewer wants to be entertained or something in the evening, no longer applies to the movies since we’ve had television. On television you have such a varied entertainment program that people who want to be entertained can certainly find something every night. For that they don’t need to go to the movies, I think. People really go to the movies in order to have new experiences–and quite consciously to have new experiences. That means I have an audience I can push and challenge to the utmost. But I’m also aware that many people see it differently […] It has nothing to do with pleasing the television audience, but simply with using narrative methods that don’t scare it off right away. It has to do with creating a consensus between oneself, the work–or nonwork–and the audience. What takes place on the basis of this consensus is another question. I don’t think I’ve ever tried to “please”, even in my work for television.'

Franz Biberkopf, to find yourself identifying with television characters

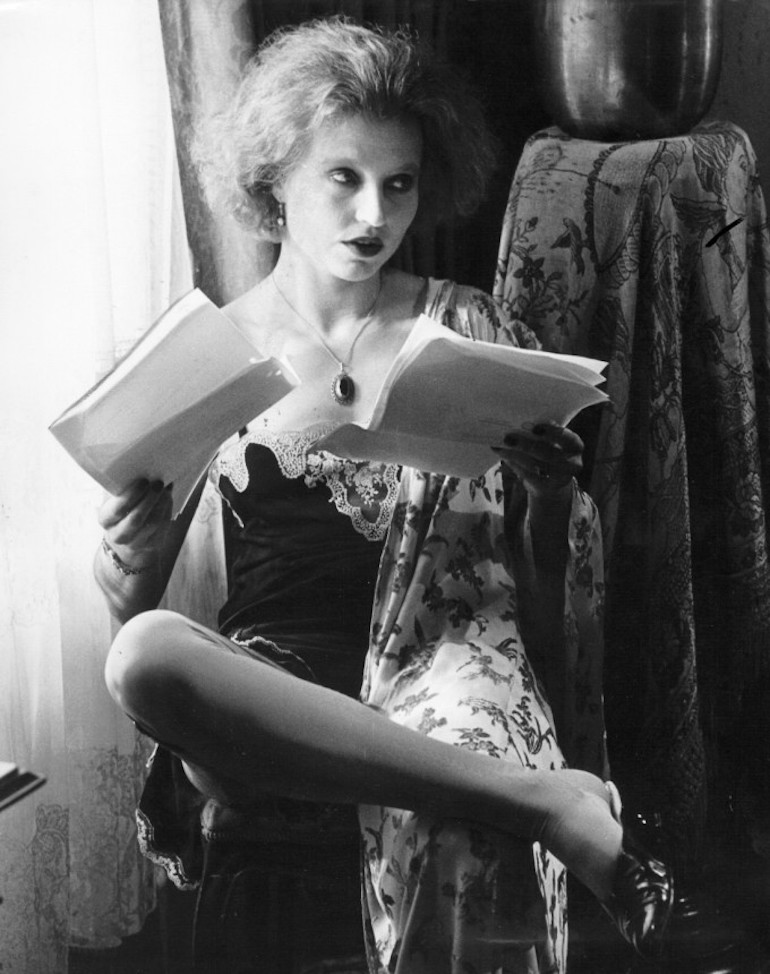

'The television version’s long enough for that, by all means. And you go through too many stages with this character not to find yourself identifying with him in some parts. I set up the role that way, too. I had two ideas about how to set up the role. One would have been to make it highly stylized, the other to open it up so you could identify with the character. I chose the latter because the script I’d written was already literary enough; I don’t need to have it stylized still further by the actors. That Günther Lamprecht, Gottfried John, and Barbara Sukowa star in the three main parts in the film has a lot to do with opportunities for identification. I hope it turns out that you’re jolted out of this identification time and again, that you have those moments of clarity in viewing the characters that are necessary to keep you from drowning in the story […] That’s why I find Lamprecht so ideal for the part, because with him you have someone who immediately evokes a lot of sympathy; so the viewer will really be irritated by the bad breaks he gets in life. That’s what I’d planned. When I was still intending to do both versions simultaneously–for reasons of economy, by the way, because of the sets–we could have used the same sets–I actually wanted to have an entirely different cast, not use the same actors at all. That has to do with having an entirely different narrative method, depending on whether you’re presenting a story in fifteen hours or only three. And Lamprecht, it seems to me, is someone who has such a broad range of expression that it can easily cover fifteen hours, but he lacks the intensity–and I don’t mean to belittle his skill as an actor–that I’d be interested in having for a two-and-a-half-hour version. For that I’d want someone whose acting was just more intense.'

Gear up, writing a hundred hours straight

'You can’t really measure how long it took me. The “original version” was about three thousand pages, and it took me an insanely short time. But it wasn’t your usual work pattern, either. I’d work for four days, then sleep for twenty-four hours, then work for four days, without interruption. Of course that puts you in a different rhythm. If you go at it the usual way, writing some in the morning and some in the afternoon, you have to gear up again every time to get back into the material. So I didn’t have that, except briefly every four days. So writing for about a hundred hours straight and only having to gear up once meant that I could write a lot faster. It’s certainly not a healthy way of writing and not one I’d recommend to anybody. But that’s what made it possible to do it in such a short time, which was how it had to be. The screenplay had to be finished by a certain time because shooting was supposed to start for The Marriage of Maria Braun (Die Ehe der Maria Braun, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1979), and all of that had to be planned out. I had only so much time, and no one believed it could be done. I wasn’t absolutely sure myself that I could do it, but I tried it this way, and it worked.'

Excerpts selected from FASSBINDER, Rainer Warner (1992). The Anarchy of the Imagination. Baltimore. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Nº 7 HOW FILMMAKERS THINK TV

Editorial. How Filmmakers Think TV

Manuel Garin and Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

Cinema and television

Roberto Rossellini

Three questions about Six fois deux

Gilles Deleuze

Birth (of the image) of a Nation

Jean-Luc Godard

The viewer’s autonomy

Alexander Kluge

Cinema on television

Marguerite Duras and Serge Daney

Critical films were possible only on (or in collaboration with) television

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Medvedkin and the invention of television

Chris Marker

TV, where are you?

Jean-Louis Comolli

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Between film and television. An interview with Lodge Kerrigan

Gerard Casau and Manuel Garin

ARTICLES

Ten founding filmmakers of serial television

Jordi Balló and Xavier Pérez

Sources of youth. Memories of a past of television fiction

Fran Benavente and Glòria Salvadó

Television series by Sonimage: Audiovisual practices as theoretical inquiry

Carolina Sourdis

The televisual practices of Iván Zulueta The televisual practices of Iván Zulueta

Miguel Fernández Labayen

REVIEWS

JACOBS, Jason and PEACOCK, Steven (eds.). Television Aesthetics and Style

Raquel Crisóstomo

WITT, Michael. Jean-Luc Godard. Cinema Historian

Carolina Sourdis

BRADATAN, Costica and UNGUREANU, Camil (eds.), Religion in Contemporary European Cinema: The Postsecular Constellation

Alexandra Popartan