TELEVISION SERIES BY SONIMAGE: AUDIOVISUAL PRACTICES AS THEORETICAL INQUIRY (WORKING/THOUGHT)

Carolina Sourdis

FORWARD

FORWARD

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABSTRACT / KEYWORDS / ARTICLE / FOOTNOTES / BIBLIOGRAPHY / ABOUT THE AUTHOR

'What must be discovered in an image is a method.'

Le Gai Savoir, Jean-Luc Godard

In 1976, the public television network France 3 broadcasts Six Times Two/On and Under Communication (Six Fois Deux/Sur et sous la communication)1, the first television series made by Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville within their recently founded company Soinmage based in Grenoble. Two years later, Sonimage produces France tour détour deux enfants2 (Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville, 1978) commissioned by Atenne 2 and with the support of The National Audiovisual Institute, consisting on a “loose” adaptation of the canonical pedagogical text of the III Republic Le tour de la france par deux enfants by G. Bruno. In this case, opposite to what is settled with the programmers, the series is broadcasted only until 1980 in 4-chapter blocks, and alternatively is premiered at The Venice Film Festival in 1979. Simultaneously, in 1977, the duo begins a two-year project in Mozambique to collaborate with the National Institute of Cinematography –a governmental entity constituted to foster the development of a local cinematographic industry in the midst of the decolonization process after their independence in 19753]– with the foundation of the first television station in the history of that country. The project is not concluded. In 1979, a series of photographs commented by Godard as summary of the experience are published in the 300th issue of Cahiers du cinema4.

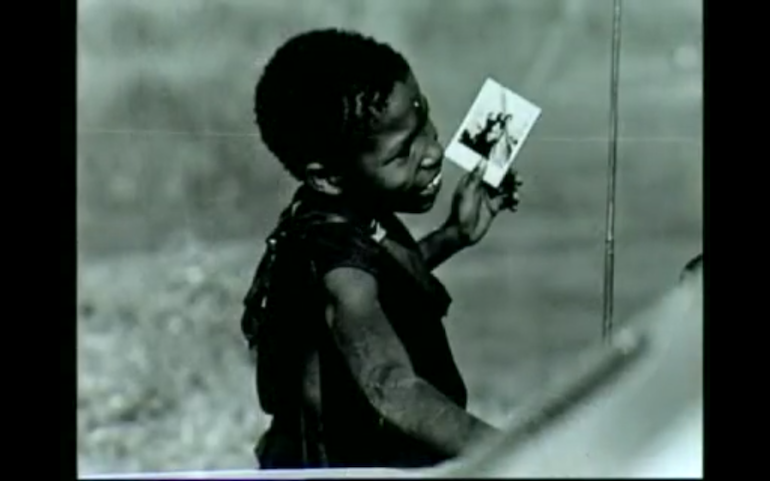

Besides including details of the daily routine in Mozambique, as a shooting diary, the document explains how the content of the series was conceived, its structure and film formats. Five films shot both in video and cinema, 8mm and 16mm, and several photographic montages, where 'the relations and the story of those (historic) relations, between a country that still has no television and a little team of television from a country that has a lot' (GODARD, 1979: 75) would be approached. The first and the fifth film would be devoted to the relationship between the producer and the announcer to frame the other three films which were planned as 'drafts, note pads, routes of thought, desires and impressions' (GODARD, 1979: 74) to express the points of view of each member of the team: the producer, the business man and the announcer-photographer. Thus, with this thread, the other fundamental purpose of the project would be developed: 'To study television before it exists, before it floods (even barely in 20 years) all the social and geographical corpus of Mozambique […] to study the image, the desire for those images, show a memory, make a mark, on arrival or departure, a line of contact, a moral/political guide, with just one purpose: the independence' (GODARD, 1979: 74).

In this way the project was intended as a research on images based on the experience of creating them: 'Two or three on the margins of television to think –and here is very important to point out that the idea of thought implicitly carries the act of creation itself– television with thirteen million still on the margins of the world. Both margins together to fill a blank page or the dark night” (GODARD, 1979: 76). Thus, the photographs that compose the brief diary of Godard’s experience are mostly of Mozambican women, men and children in an observational act, looking through the camera or at images in the monitors: the logic of shooting and editing, of making images to view them later again. These images work as an evidence of the invention of “the possibility to see that reality and reflect over it […] to research not only with words but with living matter' (GODARD, 1979: 101).

One decade before, in one of the dialogues of The Joy of Learning (Le Gai Savoir, Jean-Luc Godard, 1968) the couple discusses the method for obtaining truthful cinematographic and televisual images and sounds. They propose in first place, a stage of registration and experimentation, followed by a critical one –'We will decompose, reduce and recompose'– and a final stage to formulate a model of image and sound. Very close to this logic would turn to be Sonimage’s journey to Mozambique and, in a general outline, it could be read as the synthesis of one of the deepest concerns throughout Godard’s trajectory after May 68: the possibility to link the theoretical and the practical dimension in cinema, conceiving creative methods much more related to those scientific. Cinema –images, sounds and the countless relations between each other– as a laboratory where one searches, thinks and creates just a form to materialize ideas based on a sensitive medium: audiovisual images.

Attempting to formulate Godard’s purely platonic thought regarding television could be limited to define the edges between cinema and television based on the specificities of the formats, its exhibition mechanisms and its logics of production, considering Godard always discovers a power of sense in these, and probably, it would conclude with the undeniable supremacy of cinema over television. Nevertheless, linked to his practices, related to a certain working methodology–creation as laboratory–and to other transverse inquiries of his thought–the complex conception of montage– his television series are still a vehicle and a base to question aspects of cinema from its margins: of cinema transformed into the audiovisual. Is from that peripheral zone where Godard generates a space to question notions such as communication and the transmission and reception of information related to the dominant ideological powers, on (and under) televisual images.

The film theorist Philippe Dubois proposes Six Times Two as Godard’s last political film and France tour detour as his first lyrical work towards his rebirth in cinema. Although, in general, the last one is more studied, mostly in relation to its plastic and lyrical dimension regarding Godard’s movement experiments with the speed later continued in Slow Motion (Sauve qui peut (la vie la vie), 1979) and Histoire(s) du cinema (1988 -1998), it results significant to deepen into the intersection between the political work and the 'lyrical, artistically dense' (DUBOIS, 1992: 174) component that Godard settles within the televisual instrument. In his diary of Mozambique he writes: 'shooting rehearsal in video at the market. Not much conclusive. The material is not sophisticated at all to register the beauty of the colours. Very annoying for filming the living'; some pages later: 'second shooting at the multicolour market. Better and more calmed shots. Anne-Marie was right and Jean-Luc Godard fails. Better to shoot with super-8mm and transfer to video if necessary' (GODARD, 1979: 116). Parallel to the quest for the nascent image that pursues independence, there is a search for the light, the colour, for that 'living matter' of cinema.

In the segment entitled '6A:Before and After' ('6A:Avant et Aprés') in Six Times Two, the presenter comments retrospectively what has been intended with the series, how it is structured and the relation of the segments regarding the image production and consumption chain. He goes back over several shots that have been part of the series and reflects on the technical procedures the images have been subjected to in order to be transmitted: all images are codified, “spoiled”, 'like the image of this little boy under the brilliant sunlight […] if it was beautiful, can you imagine?' We are allowed to see the “rough” take. For the first time, the image stops being subjected to the voice of the narrator-announcer, the original soundtrack is restored.

In order to see the ‘thought’ Godard projects from television to cinema, it is necessary to study both series as a whole, with the unconcluded experience of Mozambique in between, and related to the other works made by Sonimage during the time: Here and Elsewhere (Ici et allieurs, 1974) which is simultaneously a conclusion and a point of departure, closing on the one hand Godard’s period of political militancy and opening, on the other, a period of critical reflection from and towards images and sounds; Number Two (1975), where an evident search for a technical dispositive to show the relations between images is exposed (hence the 35mm registration of multiple deployments of the monitors, of an image on top, below, aside one another); and finally How is it going? (Comment ça va, 1975), which essentially is a study on the idea of the photographic image as ‘atom’, whose frictions and interactions, properly observed, are able to create another image by comparison.

As Michael Witt argues in Godard Cinema Historian, what the filmmaker is looking for with the television series is to 'carve out a critical, oppositional space within the framework of broadcast television, simultaneously foregrounding the limitations and distortions arising from what he considers its widespread misuses' (WITT, 2013:169) through a 'complete turning of television conventions against themselves' (DUBOIS, 1990: 174). In this way it becomes fundamental to be based on the codes of television: the seriality of the broadcasts can be thought as a montage structure, the dynamic of the interview can be transformed into an expression tool or the intrusion of the presenters can be established as reflexive commentary. The work in television continues (from cinema?) as an introspective critique, from within and with image itself. Inside an image that is reflected and which discovers its own reflection. 'Always 2 for 1 image', (GODARD, 1979: 88) Godard writes. The image will always be, at least, the combination of its reflection and itself.

This exposition of the images is what Godard conceives as the filmmaker’s political work, making films “politically” rather than making political films. Godard commented on La Chinoise (1967), already a film posed as a rupture at the edge of May 68: 'I only destroy certain idea of image, certain way of conceiving what is ought to be. But I have never thought about it in terms of destruction, what I wanted was to go inside the image'. (AIDELMAN and DE LUCAS, 2010: 80). From that point forward, his cinematographic work during his political militancy would consist on ‘politically question oneself about the images and sounds and their relations (…), on not saying anymore 'is a just image' but rather 'its just an image' (2010: 90), ‘beautiful formula’ from Winds form the East (Vent de l’est, Dziga Vertov Group, 1969) that would be brought up by Gilles Deleuze to define, precisely, those ideas he had ‘seen’ in Six Fois Deux:

Just ideas are always those that conform to accepted meanings or established precepts, they’re always ideas that confirm something, even if it’s something in the future, even if it’s the future of the revolution. While 'just ideas' is a becoming-present, a stammering of ideas, and can only be expressed in the form of questions that tend to confound any answers (DELEUZE, 1976).

Closed the way for answers, questions, 'even the simplest interrogation ‘How is it going?’ transforms itself into a concrete problem' (BRENEZ, 2003: 165). Both Godard’s series for television are generated and structured through continued interrogations to different characters. In Six Fois Deux more according to an interview and in France tour détour more related to an interrogatory. If in the first one, the modelling of the discourse is given mostly by the particular knowledge of the speaker –Luison as a peasant thinks and experiences the production and labour relations in certain way, different from Marcel who as a watchmaker and an amateur filmmaker thinks and experiences others–, in the second the modelling is given by the filmmaker, the questions seem to have a common thread and lead to something that the speakers have not yet discovered. According to Deleuze’s reflections on Six Fois Deux this persistence on the interrogation is identified as a stammering, both creative and creator, which exposes doubt as the motor of creation, field that Godard will widely explore afterwards in works such as Letter to Fredy Bauche (Lettre à Freddy Bauche, 1981) Scénario du film passion (1982), Changer d’image (1982) or even later in In Praise for Love (Eloge de l’amour, 2001).

In Letter to Fredy Bauche (Lettre à Freddy Bauche, 1981) the camera repeatedly explores the landscape with random movements while the filmmaker explains in off that he is only searching for three shots with the video: the green, the blue and the step from the green to the blue, something in between. The floating movements, nevertheless, remain undefined, as if an image of a transience state. The blue does not exist, nor does the green, it is not even necessary to create them; on the contrary, the power of the work is rooted in the creation of a certain itinerary, a 'route of thought' (GODARD, 1979: 74) that becomes visible bringing to the fore the value of the interval, the movements of the camera as a thinking trace. 'When you look you track the image. If what your head does could be seen it would be like a drawing. Well, short time after your hands are no longer making a drawing because they always go in the same sense […] you forget the movements of the look, you don’t rely on them to think', claims Miéville in Comment ça va.

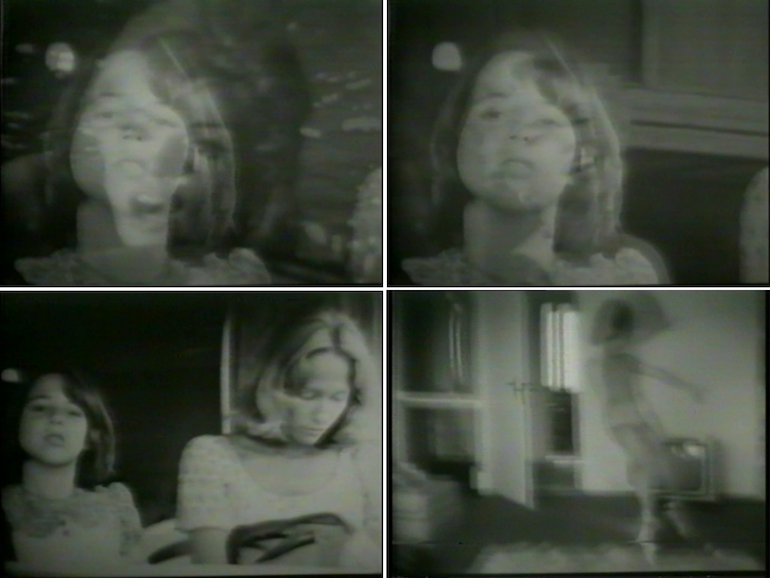

Below: Comment ça va? (Jean-Luc Godard, Anne-Marie Miéville, 1978)

Although the series constitute liminal works in his trajectory, the work by Sonimage for Television deepens the experimentation about the possible relations between sound and images, not only from an ideological perspective but questioning and thinking theoretically over the images. Why a shot comes after another? What is there between images? How to decompose their constituting parts? The linearity of the logic of language that Miéville accuses as a blind’s work in How is it going? (Comment ça va) finds in this stammering its first principle of rupture. Separate to better join. Maybe Godard and Miéville’s television practices could be considered as the first drafts for Histoire(s) du cinema, the first studies where montage started to operate as a creative tool of a virtual and poetic image, an image ‘as a pure creation of the spirit’.

FOOTNOTES

1 / Six Fois Deux/Sur et sous la communication is constituted by 6 chapters of two segments each, organized in fragments A/B, just as Godard would structure his Histoires(s) du cinema. The first segment always reflects about an element regarding the image production: production, the author, photography, screenplay, sound and montage. In the second segment, one character is interviewed to reflect on different topics: a peasant, Godard himself, an amateur filmmaker, several women, the mathematician René Thom and a couple.

2 / France tour détour deux enfants has 12 chapters named ‘Movements’. They are structured with interrogatories to two children: Camille and Arnaud. Godard interrogates them individually with different complex question about the existence, the world, work, money, images and sound. The chapters are structured as follows: 1.Obscur/Chimie, 2.Lumiére/Physique, 3.Connu/Géométrie/Géographie, 4.Iconnu/Technique, 5.Impression/Dictée, 6.Expression/Francias, 7.Violence/Grammaire, 8.Desordre/Calcul, 9.Pouvoir/Musique, 10.Roman/Ecónomie, 11.Réalite/Logigue, 12.Reve/Morale.

3 / Before 1975 some documentaries had been made about the independence processes of Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau and Angola, although they were all directed by foreign filmmakers. With the independence of Mozambique and the establishment of the National Film Institute, several programmes started to be encouraged in order to foster the local cinematographic development. For a perspective on the cinematographic situation of Mozambique see: Pasley, Victoria, Kuxa kanema: Third Cinema and its transatlantic Crossings, en Rethinking third Cinema, ed, Ekotto Frieda, Koh Adeline, 2009.

4 / The whole issue is available online at http://diagonalthoughts.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/300.pdf : Le derniere reve d’une productore, pg. 70-129.

ABSTRACT

Through the notion of creation as laboratory and the conception of montage developed by Godard throughout his works, this article analyses Godard’s thought projected from television to cinema based on the television series produced by Sonimage in the late seventies (Six fois deux and France tour détour deux enfants), and the unconcluded project developed in Mozambique for the foundation of the first television network. Related to other contemporary films made by Soinmage such as Ici et allieurs (1974), Numéro deux (1975) and Comment ça va (1975), the television series are proposed both as a vehicle and a base to question aspects of cinema from its margins, reflecting about the theoretical dimension of the audiovisual practices and deepening into the intersection between the political work and the lyrical component that Godard settles within the televisual instrument. Finally, doubt as a motor for creation is questioned based on the interrogative structure of both series.

KEYWORDS

Sonimage, Jean-Luc Godard, television series, Research, Reflection, Laboratory, Montage, Six Fois Deux/Sur et sous la communication, France tour détour deux enfants, Sonimage in Mozambique.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AIDELMAN, Nuria and DE LUCAS, Gonzalo (2010). Pensar entre imágenes. Barcelona. Intermedio.

BERGALA, Alan (2003). Nadie como Godard. Barcelona. Paidós.

BRENEZ, Nicole (2004). “The Forms of the Question” in TEMPLE, Michael, WILLIAMS James and WITT, Michael. Forever Godard. Londres. Black Dog Publishing. Pages 160-177.

DELEUZE, Gilles (1997). Negotiations 1972 -1990. Interview by Jean Narboni and Pascal Bonitzer, originally published in Cahiers du Cinéma, No. 271.

DIAWARA, Manthia (1992). African Cinema. Bloomington. Indiana University Press.

DUBOIS, Philippe (1992). “Video thinks what cinema creates” in BELLOUR, Raymond, SON + IMAGE 1974-1991. Nueva York. The Museum of Modern Art. Pages 167-182

EKOTTO Frieda and KOH Adeline (2009). Rethinking Third Cinema: The Role of Anti-colonial Media and Aesthetics in Postmodernity. Berlin. LIT Verlag

FAIRFAX, Daniel (2010). “Birth (of the image) of a Nation: Jean-Luc Godard in Mozambique” in Acta Univ. Sapientiae, Film and Media Studies No. 3. Pages 55-67.

GODARD, Jean-Luc (1979). Le derniere reve d’une producteur. Cahiers du Cinéma, No. 300. Pages 70-129.

WITT, Michael (2013). Godard Cinema Historian. Bloomington. Indiana University Press.

WITT, Michael, TEMPLE Michael, WILLIAMS S. James, et.al. (2004), Forever Godard, Black Dog.

CAROLINA SOURDIS

Filmmaker and audiovisual researcher raised in Bogotá and Barcelona. Her visual work has been exhibited in festivals in Spain, Colombia and Iran. As a researcher she has studied editing related to found-footage practices, through a grant awarded by the Colombian Ministry of Culture. She is a PhD candidate at the Communication Department of Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Her lines of research are European film essays and their convergence with cinematic theory and practice.

Nº 7 HOW FILMMAKERS THINK TV

Editorial. How Filmmakers Think TV

Manuel Garin and Gonzalo de Lucas

DOCUMENTS

Cinema and television

Roberto Rossellini

Three questions about Six fois deux

Gilles Deleuze

Birth (of the image) of a Nation

Jean-Luc Godard

The viewer’s autonomy

Alexander Kluge

Cinema on television

Marguerite Duras and Serge Daney

Critical films were possible only on (or in collaboration with) television

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Medvedkin and the invention of television

Chris Marker

TV, where are you?

Jean-Louis Comolli

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION. INTERVIEWS

Between film and television. An interview with Lodge Kerrigan

Gerard Casau and Manuel Garin

ARTICLES

Ten founding filmmakers of serial television

Jordi Balló and Xavier Pérez

Sources of youth. Memories of a past of television fiction

Fran Benavente and Glòria Salvadó

Television series by Sonimage: Audiovisual practices as theoretical inquiry

Carolina Sourdis

The televisual practices of Iván Zulueta The televisual practices of Iván Zulueta

Miguel Fernández Labayen

REVIEWS

JACOBS, Jason and PEACOCK, Steven (eds.). Television Aesthetics and Style

Raquel Crisóstomo

WITT, Michael. Jean-Luc Godard. Cinema Historian

Carolina Sourdis

BRADATAN, Costica and UNGUREANU, Camil (eds.), Religion in Contemporary European Cinema: The Postsecular Constellation

Alexandra Popartan